Raphaëlle CHELBLUNS, 1926 – 1944

Raphaëlle Chelbluns, or Chelblum (the spelling varies depending on documents), whose family preferred to call Suzanne, was born on August 31st 1926 in the 10th district of Paris.

Her father, Raphaël Chelbluns, was born in 1898 in the polish town of Nadarzyn, not far from Warsaw. He was the son of Abraham Chelbluns and Esther Zimmerman. Wounded four times during the 1914-1918 war and taken prisoner in Germany, it seems that he arrived in France in May 1920, although an official document states that he had been living there since 1913. As a stateless person, he held a Nansen passport. While living and working with his brother-in-law Salomon Ring, a tailor, at 15 Cité Marie, he met Rykla Sowa who became his mistress and with whom he moved into 43bis rue Marcadet in the 13th district.

Rykla, the daughter of Jankel Sowa and Tauba Neselrode, was born in Warsaw in October 1904. Her father, a butcher in a slaughterhouse, was a man of tremendous strength who could carry half an ox on his back.

She was only eighteen years old when she left war-torn Poland, probably in 1922, to flee the disastrous political and economic situation, unemployment and perhaps also antisemitism. She quickly learned French. She was poorly educated, but a bold, hardworking, energetic, willing woman who faced the dramas in her life courageously.

Rykla Sowa, Raphaëlle’s mother

Sadly for her, she fell in love with Raphaël. She worked as a seamstress, and her lover seemed to work occasionally although at first he called himself a shoemaker and then a tailor. Because they were expecting a baby, the couple got married on July 22, 1924. They moved to 12, rue Chapelle, where the husband was arrested five days later and imprisoned for six months for stealing and reselling two rings to a Polish antique dealer who lived at the same address. Their honeymoon was short-lived! Rykla found herself alone and pregnant. Released in December, her husband had just enough time to meet his son Abraham, born on the 14th and who carried his paternal grandfather’s first name. He was then expelled since “his presence on French territory is likely to compromise public safety”.

Rykla moved to passage Julien Lacroix in the 10th district. In June 1926, Raphaël left Brussels, where he had taken refuge, and returned to live with his wife, who was seven months pregnant. Helped by their midwife, they wrote many letters to reverse the decision to expel him from the country, claiming that he had always respected the conditions of his expulsion over a period of eighteen months. As his behavior seemed to have become exemplary, he was granted two months leave to stay until the birth of their daughter Raphaëlle, named after her father, on August 31. He then left the marital home and France for good and went into exile in Belgium, a more welcoming country.

The couple divorced in July 1931. The father paid no alimony for his two children, who probably never knew him.

No more was heard of him until June 1935. Was he living in Belgium? Was he living clandestinely in Paris? On December 25th, 1933, at the Lariboisière hospital, Isidore was born, the son of Hana Szwarc, his mistress, who he never married. He only legally acknowledged the child as his two years later, probably so as not to draw attention to himself. In June 1935, since he had not respected his expulsion from French territory, the Seine Court sentenced him to two months in prison. Upon his release, he applied to the Minister of the Interior for the right to stay in France, arguing that he had family responsibilities (his mistress already had two daughters), that he worked as a self-employed furniture and trinkets dealer and therefore was not taking the job of a French worker, that he earned 200 francs a week (about 180$) and that he had somewhere to live. This was a shack on rue Vadé, in the 13th district, a hovel that did not even appear on the 1936 population census register. The family grew larger with the birth of Maurice in July 1936. The father was granted successive three-month permits to stay in Paris. As his behavior was judged to be satisfactory, the Police Headquarters considered a six-month reprieve. The family then moved to St Ouen, where Esther was born in November 1938, and was legally recognized by her father one month later. In 1939, They moved again, to rue Bisson in the Belleville neighborhood.

The family lived in great poverty. A report from the Prefecture tells us that “Chelblum was no longer working as a travelling salesman, that he could not work in any job because his identity card classified him as “non-working”, that he lived on allowances from his mistress’s sisters, some help from a charitable society and the generosity of Polish friends. The war made matters even worse. To top it all off, in June 1940 another child was born, Jeannine, who he legally recognized as his ten days later.

Anti-Jewish measures were introduced one after another. In October 1940, Raphaël and Hana had to go to their local police station to register themselves and their children on a special register called the Tulard file. A few weeks later, a red stamp was put on their identity cards with the word “Jew” on it.

In 1941, the roundups began. Raphaël was probably arrested at the end of August 1941. Prefecture records show that he was taken to Drancy, from where he managed to escape in September. Realizing that he was no longer safe in Paris, he fled, leaving his wife and children alone in a desperate situation.

Hana was arrested on June 8, 1942, but was soon released. The family escaped the Vel d’Hiv roundup on July 16. Had they been forgotten or had they managed to stay hidden? Sadly, on August 8, the mother and her six children were taken away by the police and sent to Drancy. They stayed there until August 31, when they were put on Convoy 26, which took them to Auschwitz and to their deaths.

What had become of the father of the family? That same month of August, he was working for a Dutch company called Hegeman-Dijkman in Liesse, in the Aisne department. In November, taking advantage of a leave of absence, he left France and settled in a village near Tournai in Belgium, with false papers. His identity card, obtained in January 1943, said that his name was Maurice-Paul Simon and that he was an entrepreneur.

He was unable to escape the Germans, however, since on July 31, 1943, he was arrested and locked up at the Kasern Dozin in Mechelen near Brussels, where the Germans were gathering Belgian Jews. From there, Convoy 21 took him and 1,553 Belgian deportees to Auschwitz, where they arrived on August 3. Whether the 45-year-old man was killed in the gas chambers on arrival or selected for work remains unknown.

Raphaël Chelbluns, Raphaëlle’s father, in 1943

Now let’s return to his eldest daughter, who lived with her mother and her brother Abraham. Rykla, who worked in a restaurant, had met David Rozenbaum, born in Lublin, Poland, who she married in December 1934. Since the spring, the couple had rented a large, fairly comfortable five-room apartment at 48 rue Ramponeau in the 20th district of Paris. Little Suzanne-Raphaëlle, who was nearly eight years old, was enrolled by her mother at the school for girls on rue Tourtille. Her father’s name was not given. Hana Szwarc’s daughters would also attend the school when her father and his new family moved to rue Bisson, not far from rue Ramponeau. Perhaps the girl ran into her father in the neighborhood? That same month, on the 19th, Rykla applied for French citizenship for her daughter. No doubt she did the same for her son, who was now called Albert. A simple declaration to a Justice of the Peace sufficed since they had been born in France (law of 1927).

Albert and Raphaëlle Chelbluns, around 1942

The Rozenbaums had three children: Thérèse (1935), Edmond (1937) and Pierre (1942).

Though they were not destitute, the family lived a difficult life. Money was often lacking. The 1936 census tells us that the father was a tailor, so he had a workshop, and that the mother was known as a “finisher”. The family atmosphere was sad and strained, and the parents were strict. Rykla was harsh with her eldest daughter, who she often made cry despite her being such a kind girl. She had to take care of the little ones, take them for walks and take them to the school on rue Tourtille. Albert, held in higher esteem, was lucky enough to be out quite often. Notice that in the photo, he has an anxious expression on his face while his sister has a charming smile.

The family spoke French but the parents used Yiddish when they didn’t want their children to understand. With her friends, Rykla spoke Polish. Neither David nor his wife took any steps to acquire French nationality. The family was not religious and did not attend the synagogue.

Then came the war and its litany of horrors.

David Rozenbaum was forced to close his workshop. He was arrested in 1941 and transferred to Beaune-la-Rolande from where he managed to escape and return to Paris. Soon, misfortune befell the family yet again and he was diagnosed with cancer. The mother now had to support the family on her own, including a newborn child. She was a determined woman and worked hard on the markets. In the evenings, she came home tired and irritable, loaded down with boxes. The parents often argued.

The danger was increasing. Fortunately, in the same building there lived a peacekeeper, Henri Périllat, whose wife was a janitor with whom the family was friendly and who would alert them in case of a roundup. At night, the children stayed separately with friendly neighbors.

How could the family hope to survive? Thanks to “l’Entraide Temporaire” (“Temporary Assistance“), an organization created by Dr. Milhaud and his wife, bringing together Jewish, Catholic and Protestant activists whose priority was to save Jewish children, Suzanne and the little ones were able to be put out of danger. Mrs. Verdier, a transport coordinator from the organization, came several times to 48 rue Ramponeau to persuade the parents that they had to let their children go in order to save them.

Raphaëlle, then 16 years old, Thérèse, who was 7 and Edmond, 5, who had been given new names, left on the train with Mrs. Verdier (Pierre was only a few months old and too young to take the trip). It must have been very shortly before the Vel d’Hiv roundup, which the parents escaped, because Edmond remembers wearing the yellow star in June 1942 (his parents must have been unaware that it was not compulsory for children under the age of 6) and that on July 17, his birthday, he had already left Paris.

After sleeping in a farmhouse near the demarcation line, the fugitives set out at dawn across the fields, led by the farmer, and then walked into a wood where they remained hidden, crouching down, waiting for the German guard’s changeover to cross the line. Raphaëlle was the one who paid the farmer who helped people across the border. That evening, they spent the night near Limoges.

Finally they reached the end of their journey. Entrusted to the Cormier family on a farm in Ibos in the Pyrenees, they were saved for the time being. Albert, who was 18 years old at the time, joined them. He and Raphaëlle were happy to help with the farm work; they were cheerful, relaxed and smiling.

On an unknown date, this rural idyll was to come to an end. Raphaëlle, Thérèse and Edmond were sent to the Jewish children’s home in Moissac, in the Tarn et Garonne department, which was run by an outstanding couple named Bouli and Shetta Simon. Scouting was a daily way of life there. This home, which accommodated five hundred children, was known as a “hub”; children would arrive, and others would leave. Some attended local schools, others were apprentices with craftsmen. None of the 8,000 locals denounced them.

The length of time the three children stayed there is unknown. However, it is certain that they left no later than November 1943. A policeman having warned them of an imminent Gestapo visit, the residents were dispersed within two weeks and the home was closed down. The two younger ones were sent to Précigné, a village in the Sarthe department; Thérèse was entrusted to farmers, and Edmond was hidden in a sanatorium run by the Marianite of Sainte Croix nuns where little Pierre would later join him. As for Raphaëlle, it seems that she returned to Paris.

Her mother, who became a widow in April 1943, spent the entire war in Paris. When the Gestapo came ringing at her door, she is said to have escaped through the window, although the apartment was on the second floor, and found refuge in the home of a friend who was a policeman. With her having left to hide elsewhere, the empty apartment was requisitioned. At the end of the war, she recovered her home, the then occupants having agreed to leave.

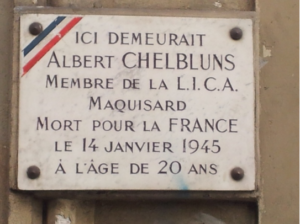

Albert, a member of the LICA (Ligue Internationale Contre l’Antisémitisme or International League Against Anti-Semitism), joined a maquis, a resistance group.. He was arrested in April 1944 and deported to the Flossenbürg concentration camp, where he died on January 14, 1945 at the age of 20. It is not known whether he was shot or whether he died of exhaustion or illness. Living conditions were terrible; the prisoners worked in the granite quarries or for the Messerschmitt factory, which produced fighter planes. After the war, since the Ministry of Defense Historical Service knew nothing of his activities as a resistance fighter, a request for FFI (Forces Françaises de l’Intérieur or French Interior Forces) recognition for Albert was rejected, but he was awarded the status of “Mort pour la France”, or Died for France.

Raphaëlle also joined the LICA, the clandestine organization charged with assisting victims of anti-Jewish laws. In addition to her activities as a maquisarde, or resistance activist, of which nothing is known, she had a salaried job as a caregiver at an orphanage (Beiss Yessoimin), at 30 rue St Hilaire in La Varenne-St Hilaire, in the Val de Marne department, which was run by the UGIF (Union Générale des Israelites de France, or Union of French Jews). There is a document in her file that describes her as a student, but her brother Edmond knows nothing about what she may have studied.

The orphanage in La Varenne-Saint Hilaire

On a clear and starry night, that of Friday 21 to Saturday 22 July, 1944, on the orders of the SS commander Aloïs Brunner, police arrived at the orphanage. Brutally dragged from their sleep, the crying children didn’t even have time to get dressed and they refused to go downstairs. The SS then fired on the façade of the building. Eighteen terrorized children between the ages of four and eleven, carrying small bundles and mattresses, as well as their four guardians (in addition to Raphaëlle were Olga Kahan, 19, Roberte Caraco, 23, and the supervisor Henriette Rochwerg, 48) who refused to abandon them, boarded buses that took them to the nightmarish Drancy camp, where they would stay for ten days. In addition to the children rounded up at the orphanage, there were ten other children from the Zysman boarding house with their director, Paulette Levi, remembered for her heroic actions, and the cook, Lucie Lithuac. Fortunately, they were all registered together and were able to remain as a group. Suzanne was given the registration number 25428. On July 31, Convoy 77 departed from Bobigny train station, bound for Auschwitz. It was to be the last deportation train from the Paris area. The Nazi leader, rushed by the Allied advance, had wanted to deport as many children as possible and conducted raids wherever he knew could find them. Less than a month later, Paris would be liberated.

The journey lasted between two and a half and four days, according to different witness statements; the prisoners were crammed in, with a hundred and twenty people per cattle car, suffocating and suffering dreadfully from thirst, with no water. Half-naked and shoeless, the children screamed in panic at night. The train arrived at its destination at nightfall.

Raphaëlle was murdered in the gas chambers on August 5, along with 847 other people, of which 324 were children, including 18 babies. She would have been eighteen years old at the end of that month. Her name does not appear in the camp’s registers; she was not even given a number on arrival. Of the 1,300 or so deportees, only 209 were to return in 1945. Survivors have described how mothers arriving at Auschwitz holding their children’s hands were immediately sent towards the trucks and the gas chambers; Raphaëlle must have been holding frightened toddlers in her arms, and thus she had no chance of survival.

When Rykla learned of her son’s death in the spring of 1945, she was so devastated that she fell down the stairs, seriously injuring herself. She was rushed to the hospital and suffered life-long injuries.

The three Rozenbaum children survived the war but their childhood, spent far away from their parents, was ruined.

Although Raphaëlle’s disappearance was recorded by the 2nd Bureau, the French intelligence service, in November 1950, her death certificate was not issued until July 1, 1953, following a judgment by the Seine Civil Court, which ruled that she had died on July 31, 1944, in Drancy. The following year, she was declared a political deportee and “Morte pour la France“, or Died for France).

It was not until 1991, however, that Raphaëlle was officially recognized as having died during deportation and her death was recorded as having taken place on August 5, 1944, in Auschwitz.

Raphaëlle’s death certificate

Raphaëlle’s name can be found at the Shoah Memorial: slab no. 8, column 3, row 2.

Two plaques placed beside the gate at 48 rue Ramponeau commemorate the tragic deaths of Albert and Raphaëlle Chelbluns.

On April 20, 1991, a memorial plaque bearing the names and ages of the twenty-eight children and their six caregivers was placed at the Hillel Center on the site of the “Orphan’s House” during a quiet and intimate remembrance ceremony.

In 2000, during the commemoration of 70th anniversary of the end of the war, a bronze sculpture made by Pierre Lagénie was placed in the center of the pond in St Hilaire square in honor of the ill-fated children.

The Academy of Créteil, in 2008, held a competition called “Une classe… des écrivains” (“One class… many writers”) gathered essays written by junior high school students. One of them is entitled “Raphaëlle” and was written in memory of Raphaëlle Chelbluns.

For her brother Edmond, Raphaëlle will always be Suzanne.

This text was only made possible thanks to Edmond who told me his sister’s story and for that I would like to thank him.

I would also like to thank the students of the J.B. Clément Paris 10th district junior high school who related the life of Isidore Chelbluns and his family.

Image library

Contributor(s)

Raphaëlle’s brother, Edmond Rozenbaum, as well as students from the J.B Clément, Paris 10th district junior high school, and especially Elsa Plot.

Français

Français Polski

Polski

bravo pour ce beau travail de mémoire et surtout le témoignage du courage de cette jeune femme de 18 ans engagée contre le nazisme et en faveur des enfants de la maison de l’UGIF. Elle le paya de sa vie. Ne l’oublions pas;

Je souhaite rester discrète sur mon identité, mais je suis sensible à cette biographie, parce que ma mère, qui est à présent au soir de sa vie, m’a toujours relaté avoir cherché une amie prénommée Sarah, originaire d’Ukraine et née en 1922 ou 1923.

J’ai écrit ce commentaire car il faut encourager tous les jeunes qui font œuvre de devoir de mémoire.

Moi-même je ne suis pas juive je me définirais comme protestante tendance “avec des questions”.

Mais je lis énormément sur cette question, cela me fait souffrir même de penser qu’on a fait “ça” à des enfants voire des nourrissons, j’ai l’impression d’un immense trou.

Voilà mon commentaire est animé d’une grande bienveillance, il faut donner de l’existence à tous ces gens disparus.

Très belle et triste histoire. Je suis devant l’immeuble du 48, rue Ramponneau et il y a une erreur de date sur la plaque, que j retrouve ici: Raphaëlle Chelbluns est en effet décédée le 31 Juillet 1944 et non pas 1945.

Monsieur, vous avez raison, il y a une double erreur sur la plaque, ce n’est ni le 31 juillet 1945 (comme indiqué sur la plaque) ni le 31 juillet 1944 que Raphaelle a été assassinée, mais à son arrivée à Auschwitz Birkenau, quelques jours plus tard.

Cordialement.

Serge JACUBERT

Bonjour, je suis la prof du collège Jean-Baptiste Clément qui a conduit le travail sur Isidore Chelblum. Je suis très contente que ce travail ait pu servir. Pouvez-vous m’indiquer comment vous en avez eu connaissance ?

Bien cordialement

Stéphanie Convertino