Rebecca FARSY, née ASIGRI (1902-1944)

This biography was written by a class of 12th graders at the Maurice Ravel high school in the 20th district of Paris, with the guidance of their history and homeroom teacher, Philippe Landru. Made up of thirty of so students, the class split into three groups to work on the biographies of three people who were deported on Convoy 77. Ten students worked on this biography of Rebecca Farsy. This year-long project was also their final-year Moral and Civic Education assignment, which was assessed as part of their French baccalaureate examinations.

After carefully studying the contents of the dossier provided by the Shoah Memorial, we set out to search for any other records that might provide further information: civil status records, census returns, cemetery registers, French national archives, police reports etc. This particular story had one distinctive aspect, however: while Rebecca Farsy was deported on the very last convoy to leave Drancy, her husband Isaac had been deported on the first! It soon became clear to us that we simply could not focus solely on the wife’s story, so we decided to look into what happened to both of them.

One of the students made contact with one of the couple’s descendants, and this heralded the start of a fruitful dialogue with several other members of the family, who were both surprised and delighted that we were interested in their ancestors’ lives. Thanks to them, we were able to gather some precious family photos (which appear later in the biography) along with two comprehensive monographs written by two of couple’s late children, Henri and Raymonde Farsy.

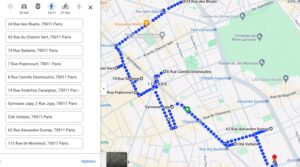

When their research was complete, the students also shot and edited a short film featuring a tour of all the places that Isaac and Rebecca Farsy would have frequented in the 11th district of Paris; the students visited the area together with Laurent Farsy, the couple’s grandson.

What follows is the result of a fascinating investigation that took us from Istanbul in Turkey, via the Vendée department of France, to Paris and the suburbs. Numerous surprises were in store for us, not least the connection between the Farsy family and the famous French composer, singer and songwriter, Pierre Barouh!

I/ THE FARSY FAMILY’S ROOTS: 19th century – 1930

Isaac Farsy and Rebecca Asigri were married in the town hall in the 11th district of Paris on March 20, 1926. At the time, he was living at 43 rue du Chemin Vert, while she was living at number 63 [1].

Family photo collection

Isaac Farsy and Rebecca Asigri’s Ottoman roots

Isaac Farsy was born on April 15, 1904 in Constantinople [2], in the Jewish quarter of Hasköy [3] to be precise. He was the son of Mercado (also known as Marco) and Rachel Eskenazi, who were both still living in Constantinople in 1926. We know that he had an older brother, Abraham, born around 1901, because he too lived in France and married Sultana Cohen on July 1, 1924, in the 11th district of Paris [4]. That same year, he was working as a tailor and living at 14, rue Godefroy Cavaignac [5]. Other than a record of his death, in 1960, there are no definite traces of Abraham Farsy [6], but we know from Henri Farsy’s monograph that there was an “Uncle Albert” who may have been this Abraham Farsi [7]. We also know from Raymonde Farsy’s monograph [8] that there was another brother, who had emigrated to Spain [9].

Abraham and Isaac’s mother was called Rachel Eskenazi: We have no details about her, but it was probably through her that the Farsy family first met the Barouh family, who we shall introduce later [10].

Rebecca Asigri [11] was born in Erenköy [12], Constantinople, on the shores of what is now the Sea of Marmara, on March 03, 1902. She was the daughter of Raphaël and Esther Juruchalmi [13]. We know from her grandson Laurent Farsy that she had at least one sister, who moved to Palestine in the 1920s[14]. However, we have very few other details about her background. When she got married in 1926, her father had already died but her mother was still alive and living in Constantinople. The same goes for Isaac Farsy: we have no information about his early life.

Isaac and Rebecca both came from the same ethnic background: they were descended from the Sephardic Jews who had been living on the Iberian Peninsula since ancient times, having been driven out of Spain during the Inquisition at the end of the 15th century. As a result of this cultural heritage, they still spoke Ladino, a Judeo-Spanish language that combines Castilian with Hebrew, Greek and Turkish idioms [15].

Google Maps – present day map of the Istanbul area

The neighborhoods from which they came from retained a distinct Jewish identity. In the late 15th century, many Jews expelled from Spain and from Portugal settled in Hasköy, formerly known as Picridion, a suburb of Istanbul on the north bank of the Golden Horn. It was home to the elite sector of the Jewish community in the 16th and 17th centuries, at the height of the Ottoman Empire.

It was there that the first Jewish printing works were founded, as well as the most prestigious educational and cultural establishments. In 1899, the huge school building of the Universal Jewish Alliance was inaugurated, an organization that played an instrumental role when Jews, such as Isaac, sought to leave the empire. It is also home to the Hasköy Jewish cemetery, the largest in the city along with the Kuzguncuk cemetery on the Asian bank of the Bosphorus. Semi-abandoned, an urban highway now runs through the cemetery. It passes by the foot of Abraham de Camondo’s tomb, a neo-Gothic mausoleum intended to remind the world of the greatness of this enterprising financier, who, although he lived in Paris, asked to be buried in Istanbul. As the city grew, these neighborhoods changed dramatically, and almost all the synagogues that once stood there were destroyed or converted.

Isaac’s move to France

According to Henri Farsy’s monograph, in which he recounted the oral account passed down through the family, Isaac Farsy left Constantinople to avoid being conscripted into the army. When Mustafa Kemal proclaimed Turkey a Republic, he made the Jews of the former empire fully-fledged citizens, thus making them liable to be recruited into the army, in which they were treated very harshly. Isaac arrived first in Marseille, on the south coast of France [16] in 1924. In her monograph, Raymonde explains that it was her father Isaac who changed “Farsi” into “Farsy” in an attempt “to make it more elegant, to give it a more French feel”.

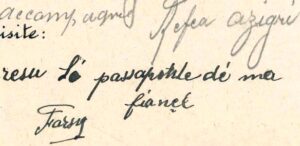

When Isaac arrived in Paris, he found a job as a laborer at Doucet, Perrier and Co, a faucet manufacturer based at 3 impasse Popincourt, where he earned 2.65 francs an hour [17]. From that moment on, he set his sights on bringing his future wife, whom he had met in Istanbul, to join him in Paris.

The only record of Isaac Farsy’s handwriting

General Security service file

A thorough examination of the archives reveals that between 1910 and 1930, large numbers of members of numerous families with genealogical links to Turkey arrived in France via Marseille. They all followed a similar migratory pattern: first the men found jobs in Paris, then they brought over their wives by various means, some more legal than others. From 1925 onwards, these same men brought over their surviving parents, brothers and sisters, uncles and aunts and so on. In the case of the Farsy and Asigri families, entire clans arrived in the French capital. We can list some of the surnames involved: Farsi, Eskenazi, Barouh, Cohen and Juruchalmi.

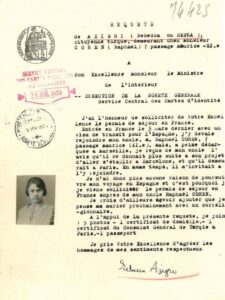

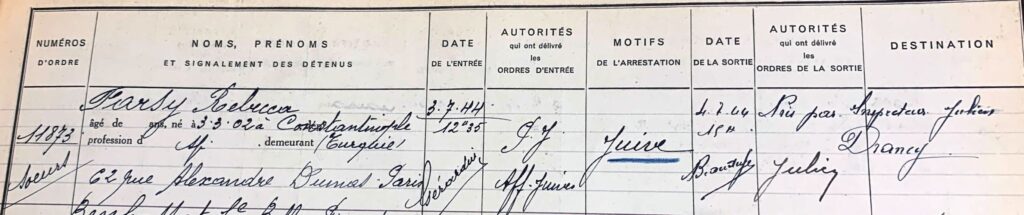

Rebecca Asigri’s arrival in France is a textbook example: Rebecca [18] arrived by an extraordinary route, details of which are included in a General Security service report. She arrived in Marseille on March 3, 1925 on a no-stop transit visa for Spain. But rather than go to Spain, what she actually did was to travel straight from Marseille to Paris, where she moved in with her uncle, Raphaël Cohen, at 7, passage Maurice [19]. She too soon found work in a factory that made metal nibs for fountain pens, on rue de Belfort, where she earned 80 francs a week. The Central Service for Foreigners’ Identity Cards soon tracked her down: in June, they issued a request for her to be turned back at the border, as she had not yet crossed into Spain. In July, they went looking for her at Passage Maurice, but a memo states that she had moved from there to 74, rue Sedaine, and that her whereabouts had been unknown since June 27 [20]. In the meantime, she had obtained from the Turkish vice-consulate in Paris a request to the French authorities for permission to remain in France “in order to enter into marriage with her fiancé, who lives in Paris”. We found a request she made to the emigration services on July 29, in which she gave the following explanation: “I entered France on a transit visa for Spain, where I was to go to live with my uncle, Raphaël Cohen […] But as soon as I disembarked in Marseille, I heard from my uncle that he was no longer planning to settle in Barcelona, and that he was in fact living in Paris […] where he invited me to go to stay with him. There is therefore no longer any reason for me to continue my journey to Spain […] I feel I should add that I am soon going to marry someone of my own faith”.

The General Security Service, in their report in November 1925, concluded: “The petitioner seems to have resorted to subterfuge in order to enter France; indeed, at the time she submitted her application, she was well aware that her uncle Rafaël Cohen, who lives at 4, rue Rochebrune, had left Spain several years earlier” (!). The report goes on to say: “Nevertheless, Miss Asigri is working legally and there are no unfavorable comments to be made.”

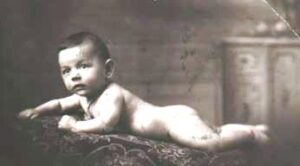

The birth of the children

And so it was in 1926, in the 11th district of Paris, in the neighborhood then known as Little Turkey (see below), that Isaac and Rebecca got married. They had a religious wedding ceremony in the kal (synagogue) at 7, rue Popincourt, which we shall cover later. The marriage was probably arranged in haste, as Rebecca was pregnant at the time. The couple moved into Isaac’s home at 43, rue du Chemin Vert, a small two-room apartment with a kitchen but with the WC on the landing, as was the norm in those days, at a rent of 45 francs a week. They were listed as living there in the 1926 census, a few months before Rachel [21], their first child, was born on August 29 1926 at the Saint-Antoine hospital in the 12th district of Paris. The little family lived a very simple life: at the time, Isaac was a delivery boy at Moline’s, the well-known fabric seller on the Marché Saint-Pierre in Montmartre [22].

Rachel – Henri – Raymonde

Family photo collection

When Henri, their second child, was born at the Saint-Antoine hospital on February 18, 1928, his parents gave their address as 8, rue Camille Desmoulins [23]. All the evidence suggests that they lived at four different addresses between 1926 and 1930, so it appears that the family got off to a difficult start. In 1930, they moved for the final time, to 62, rue Alexandre Dumas, in the 11th district, where remained until Rebecca was arrested. That same year, 1930, Yvonne, their third child, was born on April 11 in the 12th district. She did not live long, however, as she died of whooping cough at the Trousseau hospital in the 12th district on May 4, 1932 [24].

The couple’s last child, Raymonde, was born in the 12th district on March 3, 1933. The family settled permanently on rue Alexandre Dumas, as the 1931 census shows. They lived on the 3rd floor on the right hand side, in a very basic apartment, described by Raymonde as follows: the apartment overlooked “a large tiled courtyard with three other buildings on one side, and the street on the other. There was no hot water, we used a coal stove for heating, and the WC was on the landing between floors. We had a cellar and bought our coal from the “bougnat” [coal merchant].”

Photo 1: The building at 62 rue Alexandre Dumas – our own photo

Photo 2: The interior courtyard – our own photo

Page from the 1931 census

II/ LIFE AT 62 RUE ALEXANDRE DUMAS: 1930 -1939

Life in “Little Turkey” in the 1930s

Henri and Raymonde Farsy’s monographs contain a wealth of valuable material on what life was like for the family during the 1930s. By this time, Isaac had become a traveling salesman: “Bales of thick cotton stockings for discerning housewives sat side by side with boxes of rayon or real silk stockings; socks for men and children made up the balance of this mobile business. A handcart, the Quatre Saisons model, was used to transport the goods, most of which were purchased on the Sentier [wholesale market in Paris]” [25]. As for Rebecca, in thier tiny room, she produced dozens of aprons, dresses and blouses for the wholesalers on rue Sedaine.

Places where the Farsy family lived and worked

74 rue Sedaine today, the former site of the Café Bosphore. Our own photo

Little Turkey, centered around the Place Voltaire, was roughly delimited by Rue Sedaine, Rue de la Roquette, Rue Popincourt, Rue Basfroi and Avenue Ledru Rollin. Almost all Jewish migrants from the Ottoman Empire ended up here at some point, as there were a number of places where they could find help. One of the key places was the Café Bosphore, at 74, rue Sedaine. This was the first Judeo-Spanish café in Paris, having opened in 1905 in the Hôtel de l’Europe. Ladino was widely spoken. For many Jews from the Ottoman Empire, this café was their first port of call in Paris. They would meet up with relatives or friends who were already living in the area. Early on, the back room had been converted into an oratory where traditional Sephardic prayers were said in Hebrew and Ladino. Religious rites were also carried out there: brith mila (circumcision), bar mitzvahs (welcoming young boys into the adult community), weddings etc. The oratory ceased to operate when the new synagogue opened on rue Popincourt [26].

Henri Farsy described it as follows: “All Judeo-Turks were welcome there, with its friendly atmosphere. For some, it was place to play games, with poker, rummy and pastra vying with backgammon (tavli). Belote [a card game] rounded off this entertaining mix, with nothing much at stake: a packet of Gitane or Gauloise cigarettes was a jackpot for the winner. The losers’ curses in Ladino were echoed by others in French. Money, which was hard to come by for this poor clientele of small traders and laborers, was rarely seen on the tables. For many, this café-bistro was the Job Center of the day, with by a mutual help desk, a natural fit in this communal setting; for others, it was an invaluable source of employment opportunities with the promise of housing [27]”. During the war, Le Bosphore was subject to the Vichy regime’s racially discriminatory policy, and was “Aryanized”, i.e. assigned to a non-Jewish manager. The café has since closed down, but the building is still standing.

Another local landmark was the synagogue on rue Popincourt (which is also no longer there), where Isaac and Rebecca were married. It was founded on March 27, 1909 by a group of some 40 families who started a nonprofit organization called the Association Cultuelle Orientale de Paris (Oriental Cultural Association of Paris). They initially rented a silent movie theater at 7, rue Popincourt (Al Syete, or The Seven), which they bought a few years later and converted into the synagogue.

Inside the Al Syete synagogue

Shoah Memorial, Paris

In the nearby streets, the people mingled in cafés (including the still thriving Le Rey on Place Voltaire), where men met to put the world to rights over a game of cards. Meanwhile, in the Eastern-scented grocery stores, the aroma of Turkish coffee wafted through the air together with those of pastries and all sorts of fried foods.

Everyday family life

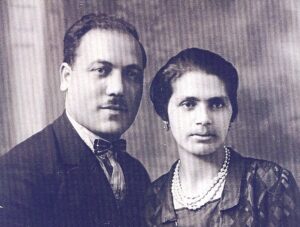

Photo of Isaac and Rebecca – Shoah Memorial

Henri and Raymonde Farsy’s recollections reflect a simple but happy life. Obviously, the parents’ day-to-day routine was laborious during the week but on Saturdays, the Sabbath, Isaac did not work. Sundays were leisure time: Isaac bought a phonograph, and by 1937, they also had a wireless radio.

They listened to Greek-Turkish music of course, but also to all the “French classics” of the day (Damia, Fréhel etc.). Sunday was also the day when the family went for their customary stroll: up Boulevard Voltaire to République, then window shopping on the Grand Boulevards and a visit to the Café Tout va bien opposite the Strasbourg St Denis station [28] [29] In summer, the family often headed to the nearby Bois de Vincennes for a picnic.

The apartment was very cramped for a family of five, especially as it was both their home and a workplace. Henri explains: “Our little tribe, with the arrival of our third child, became what was known as a “large family”. The immediate effect of this was the purchase of an extra cot, which made the main room of our humble dwelling even more crowded: the multi-purpose dining room, a whole range of functions spread over some 120 square feet: bedroom, my mother’s sewing room, study for schoolchildren, and sometimes gym, where my dear Pa did a range of exercises intended to prevent the onset of a potential bulge [30].”

“The street was alive with its endless traditional activities: the coal merchant, harnessed to his cart, delivered his hundredweight sacks of coal and coke for the hearths and stoves of the neighborhood, and the ice-cream man yelled at his horses, which never stopped at the right place. The pork butcher’s stall, with its trusty deep-fat fryer set up on the sidewalk, stank out the street with its greasy smells. Clustered around the coil of steaming black pudding on a wicker plate, a swarm of children, attracted by the distinctive aroma, would wait patiently for a cone of hot French fries generously handed out by the owner.”

“After 9 p.m., the heavy gate at the entrance to our building was closed. A pull-tab fixed to the front wall, and connected to the lodge, sounded an alert the concierge, the woman responsible for late-night arrivals, but we often had to wait a good few minutes for her to respond. Sometimes, the concierge, half-asleep or sipping her wine, couldn’t even hear it, and in this not-unusual situation, the whole family would bellow the magic words “Cordon, s’il vous plaît” [a well-known French expression at the time]. Then, like Ali Baba’s magical door, Sesame, the gate would open [31]”

As for the children, their daily routine was divided between school and hanging out with friends. All the Farsy children went to the Cité Voltaire nursery school [32]. Here is what Henri Farsy had to say: “Wearing a black gingham apron, I became part of the flock of little boys and girls who obeyed the teacher’s every command.

The Cité Voltaire school – Our own photo

At lunchtime, all these little people would sit down on a long bench in front of an endless low table, where everyone made sure they had room by using their elbows to their advantage. A huge flask of soup contained vital nourishment for the youngsters.

Henri (circled) in nursery school

Family photo collection

My class was a typical reflection of the neighborhood, with a high proportion of children whose parents came from a variety of foreign backgrounds and religions. Italians, Poles, Russians, Turks and Greeks [33]”. As the only boy in the family, Henri had a whole gang of friends.

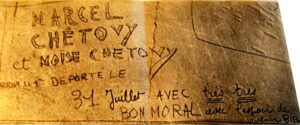

He wrote about this in his monograph: “The 14th of July celebrations were organized between friends. Each of us paid the obligatory contribution to the great master of ceremonies, our elder, Marcel Chetovy [34], who was in charge of the preparation and flawless organization of this day of public festivities.

Marcel Chetovy’s name carved into the wall at Drancy camp – Drancy Memorial

As night fell, the fireworks display began. With each detonation, the multicolored flowers burst open, exploding to the delight of the audience, always eager for more. These national celebrations took place at 113 rue de Montreuil, in a derelict courtyard. Few tenants would have lived in these shabby, uncomfortable old terraced buildings, apart from three destitute families from Istanbul: the Covos, the Eskenazys and the Chetovys. A pedestrian walkway linked Rue Alexandre Dumas and Rue de Montreuil, facilitating interaction between friends of the same religion [35]”.

During vacation, the family often went to Champigny-sur-Marne, in the Val-de-Marne department of France: Elie Eskenazi and his wife Esther Sephiha, Sarah Barouh’s parents, had built a house there, and the Barouhs often met up there. When paid leave was introduced in 1936, Rebecca their first vacation to Bercq, on the north coast of France, as can be seen from a photo. They also went there so that Rachel, who leg trouble, could have some medical treatment in the well-known sanatorium.

The family on vacation in Berck (Rebecca is in the back row, on the right)

Family photo collection

The Barouh family

We know that the Farsy family had a very close relationship with the Barouh family. Raphael Barouh was Isaac’s cousin and his best friend [36]. We were unable to find out exactly how they got to know each other, but it is highly likely that the connection was made via the Eskenazi family: Isaac Farsy’s mother was Rachel Eskenazi, and Raphaël’s wife was Sarah Eskenazi. In 1911, when Sarah Eskenazi was two years old, she arrived in France together with her parents Elie and Raquel, her three brothers and her sister. As for Raphaël Barouh, his story was similar to Isaac Farsy’s: born in Constantinople in 1909, he left Turkey on his own when he was eighteen in order to avoid national service. Sarah’s father was a skilled tailor who had once worked for the Sultan. The Eskenazi family had moved to Levallois-Perret, in the Paris suburbs. Raphaël Barouh came from a humbler background: a lace seller in the streets of Constantinople, he became the family breadwinner at the age of twelve when his father, who was a cobbler, drowned in the Bosphorus after a large ship capsized his little boat, called a caïque. When Raphaël arrived in France, he worked in a bar on the port in Marseille, where he earned enough money to get to Paris. He started out on the markets in the western suburbs, and went into the hosiery business, which is how he met his future wife. He then brought his mother, Vida, also known as Victoria, Levy, and his three brothers, Nissim [37], Dario and Victor [38] [39] to join him in France.

Raphaël Barouh et Isaac Farsy

Family photo collection

Raphael and Sarah thus live in Levallois-Perret [40]. They had three children, all of whom can be found in the Levallois-Perret birth register and in census records: The first was Samuel, who was born on July 31, 1930 in the 15th district of Paris and who, from the 1940s onwards, was known by the name of Claude. Between 1958 and 1965, he was married to his “cousin” Raymonde Farsy, Isaac and Rebecca’s youngest daughter. Their second child was Elie, who was born on February 19, 1934, also in the 15th district of Paris, and who was renamed Pierre in the 1940s: he became world-famous as an actor and above all as a composer, in particular for the songs he wrote for Claude Lelouch’s film Un homme et une femme (including the title song, with music by Francis Lai), and for Yves Montand’s hit song La bicyclette. Their third child, a daughter, Estelle, was born in May 1940.

We know that the Farsy and the Barouh families saw each other often. They celebrated Jewish holidays together, for example, alternating between the Farsys’ small apartment on rue Alexandre Dumas and the Barouhs’ home in Levallois-Perret. Henri Farsy’s monograph reveals that the family’s approach to Judaism was more cultural than strictly religious, and that religion did not exactly play a major role in the family’s day-to-day life [41]. It also reveals that while the Farsy family had no overt political affiliations, they tended to lean to the Left.

A Barouh family wedding – Rebecca and Isaac are circled in the back row of the photo

Family photo collection

III/ THE WAR AND THE DEPORTATION: 1939 -1944

Clouds on the horizon: 1939-1940

When France joined the war in 1939, the Farsy family was inevitably alarmed. Although no anti-Semitic policies had yet been introduced in France, the family had been closely following developments in Eastern Europe for several years. “Uncle Albert” joined the Chasseurs Alpins (the Alpine Hunters, the mountain infantry) at the start of the conflict, and Isaac too decided to enlist: he was supposed to be drafted to Bordeaux, but as the situation was somewhat chaotic, he ended up stuck in Paris. The family did not leave during the exodus, although they had intended to. Isaac managed to find a handcart, but by the time they needed to flee, it was already too late: the Germans had arrived in Paris.

In 1940, the discriminatory legislation affected the family for the first time: Henri, despite being a brilliant student, was refused admission to the Dorian high school because of his parents’ foreign roots. He enrolled in a part time industrial course on rue Trousseau, but soon dropped out and found work with a varnisher on rue Godefroy Cavaignac in the Cité du Meuble (Furniture quarter).

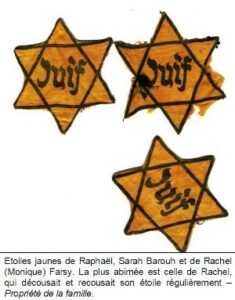

In 1940, when the Vichy government came to power, the situation deteriorated further: Isaac and Rebecca were foreign Jews, albeit from Turkey, which meant that they benefited from a specific legal status [42]. Nevertheless, their French Jewish children, who had to wear a yellow star from May 1942 onwards, became potential targets for the occupying forces [43]. In addition, their cash flow became increasingly unpredictable: orders from wholesalers for Rebecca dropped significantly. In exchange for sewing work, Rebecca was sometimes given fabric to clothe the children and sweetened condensed milk.

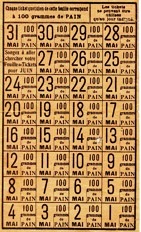

We know that Isaac, in common with so many other people, had to turn to the black market and the “D system” to provide for his family. Isaac, who never smoked, gave his tobacco tickets to his brother, who smoked a lot. With the help of his contacts, Isaac bought counterfeit tickets, some of which were poor quality. There were no more strolls along the boulevards: even before the roundups began, the Farsy family left home less often for fear of arrest. It must have been tough for the five of them, with two teenagers and a child, living cooped up in such a tiny apartment. Little Turkey became a shadow of its former self. The lively hustle and bustle in the streets was replaced by a sense of dread and the need to make essential journeys as quickly as possible. The Ashkenazi Jews from Poland suffered the worst discrimination of all, on account of their supposedly “disgusting” accent, as Roger Ikor was to write some years later in his best-selling book Les eaux mêlées (Mixed Waters). Even Rebecca Farsy herself, along with many of her Sephardic friends, joined in this unjustifiable criticism, referring to them as larhlis sousios (dirty Poles) [44].

Isaac’s arrest: August 22, 1941

From August 20 to 24, 1941, a series of major roundups took place in Paris. The first of them was on August 20, in the 11th district. At the end of this first day, in line with the target set by Theodor Dannecker, the German officer behind the roundups and deportations in France between 1940 and 1942, 5,700 Jews were arrested, of which 3,000 were interned. Dannecker then announced that he wanted to make another 1,000 arrests. The roundups, which lasted until August 24, included some other districts. During the roundup, the French police, working in collaboration with the German Feldgendarmerie, arrested only French and foreign Jewish men between the ages of 18 and 50. A total of 4,232 people (out of the 5,784 on the lists) were arrested and interned in Drancy Among the men rounded up on August 22 was Isaac Farsy. Here is his son Henri Farsy’s account of what happened:

“On the morning of August 22, as I did on every day of the week except Saturdays and Sundays, I set off for my little summer job [45]. Our usually relatively quiet street resounded with a most unusual din, and seemed to have taken on a totally unfamiliar look. Followed by police cars, Parisian buses drove up and down the street, overloaded with bewildered-looking passengers, all clutching either a small suitcase or a shapeless bundle, all bearing silent witness to their sudden arrests and hasty departures. My father, at home that day, watched, intrigued, from behind the curtains, the incessant merry-go-round of all these vehicles. Clearly, the hunt was on for the Jews, who, according to the anti-Semitic press, were to blame for all the woes of the French nation. My dear Pa, not seeing any suspicious activity in the immediate vicinity of our entrance gate, recovered the composure which, to all appearances, had never before left him. Perhaps all these happenings only involved Jewish individuals from Germany, Poland and Russia? And not those from the former Ottoman Empire, the Turks, Greeks and Bulgarians? Pedestrians hurried along, while the countless buses carrying the initial victims of this gigantic roundup waited patiently for their turn to unload their human cargo at a sports center: the Japy gymnasium.

My father had already made up his mind: to wait stoically until he was arrested. And, indeed, it was not long before this proved to be the right thing to do. A few knocks on the door, followed by the words “Police! Open up!”, were enough to terrify the entire family. And there was my dear Pa, all set to go with the French Police Inspector. And it was just the same scenario for the other victims: After a brief identity check, “Are you Mr. Isaac Farsy?” and my father’s acknowledgement, the customary “Please pack some clothes and a toilet bag and come with us” soon followed. My father gave us all a big hug, squeezing us harder than usual. Did he have a premonition that he was leaving us forever with no hope of ever coming home? [46].”

The anguish: August 1941- July 1944

From the moment that Isaac was arrested, the Farsy family was caught up in a downward spiral that culminated in Rebecca too being arrested and deported.

Isaac, like most of the men rounded up from the district, was initially taken to the Japy gymnasium. What happened next is less clear: firstly, he was taken to Drancy. We gather from the Farsy monograph that he sent a few letters to his family, including one asking them to send him a parcel. We also know from Raymonde’s monograph that Rebecca and Rachel were able to see him in Drancy, albeit from a distance, through an outside-facing window.

He was a kitchen worker and helped others (some of the people who were released from Drancy sent thank-you gifts to the children at Christmas time in 1941). Isaac suffered from sinusitis, and it seems he asked Rebecca to send him a doctor’s certificate in order to be allowed out, as had happened to a number of other fortunate people. But alas, it was too late: on December 12, 1941, Isaac Farsy was one of 298 prisoners [47] who were transferred from Drancy to the Royallieu camp, near Compiègne, in the Oise department of France, where he joined the ranks of the prisoners who had been arrested as part of the notorious “rafle des notables” (“Roundup of the Notables”) [48]. Along with them, he was deported to Auschwitz on March 27, 1942, on Convoy No. 1. [49]. Isaac was not sent to the gas chambers as soon as he arrived in Auschwitz, but died two months later of typhus. A transcription in the civil register of the 1st district of Paris, dated April 22, 1947, records his death as having taken place on May 5, 1942.

Of course, we can only imagine how worried the family in Paris must have been, not knowing what had become of him. Rebecca found herself alone with three children, so she too had to resort to the black market. The fear being rounded up was worse than ever, and the family, when Rachel warned them that a raid was imminent, went into hiding for a whole night.

The last photo of the family, which was sent to Isaac at Drancy but which almost certainly never reached him – Family photo collection.

In 1943, Rachel Farsy, who by now was calling herself Monique, got her a job for her brother Henri with an art restorer on the rue du Faubourg Saint-Honoré. That left only the youngest daughter, little Raymonde, who was eleven years old at the time.

In February 1944, Raphaël Barouh, who had become “the man of the family” in this patriarchal community, suggested that Rebecca send Raymonde out of the city. One of his clients had told him that there were families in the Vendée department who were taking in Jewish children, and so Raphaël had already sent his two sons, Elie (now known as Pierre) and Samuel (Claude), to Montournais, where they had been taken in by two different families and sent to two different schools, in order to arouse as little suspicion as possible. Raphaël, his wife and their young daughter Estelle, had managed to get false identity cards in the name of Biet, and moved from Levallois-Perret to a smaller, more discreet apartment building on rue Montempoivre, in the 12th district of Paris. At this point, and with the net closing in on the Jews in the city, a distraught Rebecca finally agreed that Raymonde should leave. On February 9, 1944, Sarah Barouh, who had to go to Vendée to hand over little Estelle, took Raymonde with her on February on what was obviously a risky journey. They took a train to Pouzeauges, where the baker’s son from Montournais was waiting for them. He took them to meet Mr. and Mrs. Podevin, an elderly couple who had no children and were very religious: they had no idea that Raymonde was Jewish to begin with, and sent her to a school run by nuns (they did not approve of secular schools). When they found out that Raymonde was Jewish, they sent Rebecca an angry letter, threatening to send her back to Paris [50]; it was therefore decided that she should be baptized as a Catholic, much to her mother’s dismay, and make her first communion. Raymonde soon became deeply devout: after all her Catholic upbringing hardly clashed with her previous Jewish religious education, given that she had never had any.

Photo taken in the Vendée in 1944: Hilaire Rocher, Pierre Barouh, Raymonde Farsy and Serge Rocher – Family photo collection

Rebecca’s arrest: July 4,1944

By early July 1944, the Farsy family’s optimism began to return: the Normandy landings had taken place, and the Allies were closing in on Caen. But then on Sunday July 2, the Barouhs went to see Rebecca to beg her to leave her apartment, as all Jews were now being rounded up individually in their homes.

On the morning of Monday July 3, Henri Farsy went to work. At 12:35, Inspector Julien came to their apartment to arrest Rebecca, on the grounds that she was an “Israelite”, i.e. Jewish [51]. The apartment door was sealed immediately. At 3:00 pm the following day, Rebecca was taken to Drancy internment camp, where she was assigned the number 24.851. It was then that she realized what had happened to the most recently rounded-up prisoners, including the Moïse Chetovy, as mentioned above, who were no doubt torn between terrible anguish and the hope of imminent liberation.

On July 31, seventeen days before the camp was liberated, Rebecca was deported on Convoy 77 from the Bobigny train station to Auschwitz. The train arrived in the early hours of August 3 and the “selection” took place immediately: Rebecca was among the 847 deportees who did not even enter the concentration camp, but were sent straight to the gas chambers and murdered. Her death certificate, issued in the registry office in the 11th district of Paris in 2014, states that she died on August 5, 1944. This is the official date of death of all the unfortunate souls who died as soon as they arrived in Auschwitz.

Somewhat ironically, although it is not the only case like this out of all the French Jews who were deported, the Farsy family’s story covers the entire chronology of the persecution: while Isaac was deported on the first convoy to Auschwitz, Rebecca was deported on the last!

Epilogue

The Farsy children survived the war under the guardianship of their “Uncle Raphaël”. It would be inappropriate to discuss their numerous descendants in this biography, as their lives are private and outside the scope of the Convoy 77 project. Henri and Raymonde have now passed away (Raymonde was the last to die, in 2020, in Nice), but (at the time of writing, in June 2024) their eldest sister, Rachel (Monique), who never married nor had children, is 98 and still lives in rue Alexandre Dumas (although no longer at number 62). The Farsy and Barouh families still keep in touch from time to time.

Notes & Sources

[1] The two buildings where they once lived have disappeared and been replaced by modern buildings.

[2] Now Istanbul.

[3] Henri Farsy, Une vie farsy de souvenirs, family monograph, p.9

[4] He divorced her in 1953, as recorded in a note in the margin of their marriage certificate.

[5] The building has recently been demolished and will soon be replaced by a new one.

[6] A Rachel Farsy, born on May 16, 1925 in the 11th district of Paris could be Abraham’s daughter.

[7] We found Abraham Farsi’s death certificate, which states that he was divorced from Sultana Cohen: he died at the Salpêtrière hospital ( in the 13th district of Paris) on October 26, 1960. He was listed as living in the 20th district, at 8 rue des Vignoles, in a building that is still there today. An interesting aside: on his death certificate, he is described as the son of Judas Farsi and Rachel Eskenazi. Might Abraham and Isaac’s father have actually been called “Raphael Judas”? Laurent Farsy has never heard of Abraham, which would suggest that the two branches of the family no longer saw each other. We know that the spelling of surnames can vary: all of the records relating to Isaac are written as Farsy, while those relating to his brother are written as Farsi, which would seem to be the original spelling.

[8] Raymonde Farsy, Mon enfance à Paris, family monograph, p.6

[9] We have no further information about him.

[10] The current representatives of the family do not know the exact genealogical link between them.

[11] Sometimes spelled Azigri.

[12] Henri Farsy, ibid

[13] The spelling differs from source to source, but it may be a variant or a corruption of Jerusalmi.

[14] There are descendants.

[15] We know from Raymonde’s monograph that Isaac could read French, but Rebecca could neither read nor write it. They spoke Ladino with each other, and a mixture of Ladino and French with the children.

[16] The arrival point in France of almost the entire Jewish community from the East.

[17] Information from the General Security service file.

[18] In the early records, she was often called Refka, or Ribka. From the 1930s onwards, she became known as Marguerite.

[19] Now rue du Morvan (11th district of Paris).

[20] She actually lived on rue du Chemin vert.

[21] In keeping with tradition, she was named after her paternal grandmother, but soon adopted the name Monique.

[22] He got the job through the influence of his “cousin” Raphaël Barouh. Raphaël, who lived in Levallois-Perret, knew Edmond Dreyfus, who co-founded with Armand Moline the boutique that opened in the Saint-Pierre market. The “Moline” store, founded by Armand’s father in 1879, was located in Levallois before moving to the 18th district. Raphaël Barouh introduced several family members and friends to Moline.

[23] At the same time, the Eskenazi family, including Elie, Sarah’s father and Raphaël Barouh’s future father-in-law, lived at number 4 of the same street.

[24] The changes in the couple’s children’s first names bear witness to their increasing cultural integration. Little Yvonne was buried in the 44th division of the Pantin cemetery in Paris, in what was no doubt a very humble grave, which has since been reclaimed.

[25] Farsy Henri, ibid p.12

[26] Annie Benveniste, Le Bosphore à la Roquette – La communauté judéo-espagnole à Paris, 1914-1940, L’Harmattan, 1989, and Bosphore.pdf (free.fr)

[27] Henri Farsy, ibid, p.13

[28] There is now a Monoprix on the site

[29] Henri Farsy, ibid, p.22

[30] He had bought an Extensor machine to work out at home!

[31] Henri Farsy, ibid, p.23

[32] By coincidence, two of our 12th grade students also went to this nursery school!

[33] Henri Farsy, ibid, p.17

[34] He was to go down in history in a tragic fashion: arrested on July 1, 1944, he was interned at Drancy. The reason his name is well known is that he created a piece of graffiti, dated July 31, 1944, which is still in existence in the Cité de la Muette: “Marcel Chetovy et Moïse Chetovy / arrivé le1er/ déporté le 31 juillet avec très très bon moral avec l’espoir de revenir bientôt” (“Marcel Chetovy and Moïse Chetovy / arrived on July 1/ deported on July 31 in very, very positive frame of mind and hoping to be back soon”). The Normandy landings had taken place almost a month earlier, and the Allied troops were advancing through Normandy. We can well imagine that those leaving on what were to be the last convoys to Auschwitz, obviously unaware of the death factory that it was, still hoped that the liberation would happen soon. He was in fact deported on Convoy 77 with Rebecca Farsy, and, like her, never came back.

[35] Henri Farsy, ibid, p.33. The premises still exist, although they have changed a great deal, but the pedestrian walkway Henri refers to has long since vanished to make way for a new building.

[36] There is no doubt that the two friends were cousins, even though the connection has yet to be found. This link is confirmed not only by the monographs (including that of Sarah Barouh), but also by a detailed study of the genealogies of the Eskenazi, Farsy and Barouh families. This fact is worth emphasizing, given that some members of the Barouh family now believe they were just friends.

[37] The family’s lineages are intertwined: Solange Cohen, Henri Farsy’s wife, was the daughter of Nissim Barouh’s wife from a second marriage!

[38] Benjamin Barouh, Savanah – C’est où l’horizon ? 1967-1977, ed. Le Mot et le reste, 2018.

[39] Unlike the Farsy family, they all managed to avoid being deported.

[40] As previously mentioned, Isaac Farsy got the job at Moline through his cousin’s connections.

[41] This very limited religious observance appears to have been the norm in the Little Turkey neighborhood. There were two or three butchers’ shops opposite the six cafés-restaurants in the neighborhood, for example, and none of them were kosher (i.e. they did not follow the strict Jewish rules relating to food). Nevertheless, we know that Henri became a bar mitzvah, having been instructed by the rabbis on rue Popincourt, and that Isaac and Rebecca went to synagogue for Yom Kippur.

[42] Hitler spared Turkey, a neutral country, in the hope that it would join the Axis forces.

[43] Raymonde says that Rachel kept sewing on and then removing her star so she could go to the movies.

[44] Henri Farsy, ibid, p.43. The dark side of human nature that makes persecuted people find others even more persecuted than they themselves are!

[45] Henri’s employer, who believed that his Ottoman citizenship entitled him to protection, was arrested on the same day as Isaac.

[46] Farsy Henri, ibid, p.49-52

[47] His name is stated on the list of 298.

[48] Which took place on that very day, December 12, 1941.

[49] Having departed from Le Bourget station, near Drancy, this convoy stopped off at the Royallieu camp near Compiègne, where 547 men from the August 1941 roundups (during which Isaac was arrested ) and the December 1941 “roundup of the notables” were loaded onto the train during the night.

[50] The couple knew nothing about Jews other than that they “had crucified Christ”. Far from the roundups and deportations in Paris, they had no idea of the danger that Raymonde would face if she returned home.

[51] Both Henri and Raymonde, in their monographs, claim that she was arrested just before 8 a.m., after going out to buy bread. Raymonde even goes on to say that the inspectors went to look for her at school, but when they failed to find her, they harassed Rebecca to find out where she was. It was also suggested that someone had turned the family in. As neither of them were actually there at the time, little credence can be given to what later became a family legend.

Français

Français Polski

Polski