Salomon BERKOVICI

Following in the footsteps of Niche and Salomon Berkovici

Contributors

As part of a joint cross-disciplinary (history/ literature) project (involving several classes of ninth grade students) at the Voltaire secondary school in the 11th district of Paris during the 2020-2022 academic years, a large number of students were involved in analyzing dossiers about people who were deported on Convoy 77. During the Second World War, these deportees lived in the 11th district of Paris, the same area in which the students live now.

This biography was written by Carmen Kwiat and Hannah Tanguy from class 3e2.

Introduction

We decided to produce a joint biography of Niche Berkovici and her son Salomon in order to present a more detailed account of the life of both mother and son, about whom very few records were available, and to retrace their life stories[1]. Due to the Covid 19 restrictions, we were unable to explore as many avenues of research as we would have liked. If, therefore, having read this biography, you have any information to add or to share with us, please do not hesitate to contact us by e-mail at hglyceevoltaire75011@gmail.com.

Family background: Russia, Poland and Romania

Niche Blimbaum, Salomon’s mother, was born on April 17, 1902 in Zgierz, a town north of Lodz in Poland, where her parents Mostzek Blimbaum and Chaja Sura Kadecka lived.

Salomon’s father, Moïse Berkovici, was born on February 12, 1904 in Dorohoi, in Romanian Moldavia. This was an area to which many Ashkenazi Jews, who had fled Russia and Galicia, had moved and formed a thriving Jewish community. Salomon’s paternal grandparents, Joseph Berkovici (who was an upholsterer) and Clara Berkovici née Abot, stayed on there, so he never met them.

People from Central Europe moved to Paris

From the early 19th to the mid-20th century, France was a favorite destination for Jewish people from Europe. Moïse, like many others, fled anti-Semitic attacks, discriminatory policies and poverty. The fact that he chose to move to France was probably due to its liberal immigration policies and access to French citizenship[2], which would have given him hope for the future.

Moïse’s arrival in Paris

When Moïse arrived in Paris on April 4, 1920, he was 17 years old. He lived at 14, rue Godefroy-Cavaignac in the 11th district, probably staying with relatives initially[3]. Jews from Romania often settled in the 11th district when they first arrived in France[4].

As for Niche, we were unable to find any details about when she arrived in France. She must have left her homeland to escape anti-Semitic discrimination and poverty, just as Moïse did. She most likely arrived sometime between 1920 and 1931[5], and she too probably settled in the 11th district, because when she got married, in 1934, her address was 48, rue Godefroy-Cavaignac, in the Roquette neighborhood.

The new arrivals, who were usually quite poor, tended to live in very basic accommodation, in buildings with tiny, uncomfortable apartments, or sometimes in cheap hotels.

When he was 17, Moïse was arrested for stealing a coat and on April 9, 1921, a juvenile court sentenced him to detention in a penal colony until he came of age. While in detention, he signed up for a five-year contract with the French Foreign Legion. In the early 1920s, he took part in colonial campaigns in Syria and Morocco.

When he was discharged on December 21, 1925, he went to stay at 53 rue de Montreuil, in the Sainte-Marguerite neighborhood of the 11th district of Paris, with a fellow countrywoman, Creuta [6] Harabagui (married name Idlik)[6], who was born on January 2, 1901 and was separated from her husband. She came from the same area as Moïse[7]. Moïse and Creuta had a son, Samuel, who was born on October 28, 1927 in the 11th district of Paris, and was therefore Salomon’s half-brother.

In the late 1920s, when he had been living in France for nine years, Moïse, like many other foreign citizens, applied for French citizenship. On August 8, 1929, Moïse Berkovici was granted French citizenship by decree[8].

Niche and Moïse

On May 27, 1931, Moïse re-enlisted in the army and was posted to a colonial infantry regiment.

He probably met Niche Blinbaum for the first time when he was home on leave. Niche was then living at 48, rue Geoffroy Cavaignac in the 11th district of Paris, while Moïse was staying in a hotel at 31, rue Keller, also in the 11th district[9]. They got married on March 6, 1934, in the town hall of the 11th district.

Two months later, on May 27, 1934, Moïse was demobilized and presumably went back to working as a labourer.

Later that year, on November 24, Salomon was born in the Adolphe Pinard maternity wing of the Saint-Vincent de Paul hospital at 74, rue Denfert-Rochereau, in the 14th district of Paris. Between 1934 and 1936, the couple moved to 62 rue de Ménilmontant in the 20th district[10].

When Salomon was barely two years old, on November 10, 1936, Moïse volunteered to go to fight with the Spanish Republicans[11]. Niche and Salomon were left alone for four months until Moïse was repatriated from Valence in early February 1937[12].

In 1937, Moïse worked as a laborer at the Gallay metal barrel factory at 116 rue Saint-Honoré in the 1st district of Paris. Before the war, Salomon may well have gone to the Ménilmontant nursery school[13].

The war and the beginning of the discrimination

When war broke out, Moïse was drafted into the 223rd Territorial Reserve Regiment on September 13, 1939. Niche and Salomon found themselves alone again, and Moïse was soon taken prisoner.

They may have already moved to 18, passage Gustave Lepeu in the 11th district, since Salomon went to the nearby elementary school for boys (now the Leon Frot school) at 129 rue des Boulets.

Moïse and his family soon felt the effects of the “National Revolution” and the Vichy government’s anti-Semitic policies. As was the case for many foreigners who had become French citizens since 1927, Moïse’s French nationality was reviewed according to the Act of July 22, 1940.

When, on September 27, 1940, the Germans required all Jews living in the occupied zone to identify themselves, Niche, along with many other people, had to go to the police station in the 11th district to register. All Jews had to register between October 3 and 20, 1940. In the Seine department, they were listed in what was known as the Tulard file.

On October 3, 1940, the Vichy government enacted the first decree on the “Status of Jews”[14].

On March 27, 1941, having been gone for over six months, Moïse was repatriated to Paris on a medically equipped train. Niche and Salomon must have found it reassuring to have him back home.

Daily life was already difficult for the people of Paris, who were suffering from the hardships caused by the Occupation and food shortages, but for Jews, things were even worse.

As of April 1941[15], the Germans forbade Jews from running businesses and limited the occupations in which they were allowed to work. This made it difficult for Moïse and Niche to find work and support their family.

They were no longer allowed to have radios, bicycles or telephones.

The second decree on the Status of Jews, dated June 2, 1941, increased the scope of the exclusion of Jews from public life and intensified the discrimination against them.

As of February 1942, the family was subject to the 8pm to 6am curfew applicable to Jews. Niche was only allowed out to do her shopping between 3pm and 4pm. As a result, the young Salomon’s life changed along with that of his parents, who were subjected to increasingly severe restrictions.

On May 29, 1942, another law was enacted, this time requiring Jews to wear the yellow star when they went out. Niche and Moïse had to buy the stars and sew them onto their clothes before the law came into force on June 6. Seven-year-old Salomon had to wear his star on the way to and from his school, on rue Bréguet. If people did not wear the star, or did not wear it according the rules, they could be arrested and deported. Then, from early summer 1942, Salomon, like all Jewish children, was no longer allowed in public gardens or swimming pools, or to go to summer camps.

Moïse’s former partner, Samuel’s mother Creuta Idlik, was arrested during the Vel D’hiv roundup on July 17, 1942. She was interned in Drancy camp for a few days and then deported to Auschwitz on Convoy 11. She never returned to France. It appears that Samuel, Salomon’s half-brother, somehow avoided being arrested.

The roundups and arrests continued. To avoid being hunted down, Jews had to move from one place to another and find somewhere to live. In 1943, the Bercovici family was living at 18, passage Gustave-Lepeu in the 11th district of Paris, so they too had moved house.

18 passage Gustave Lepeu in the 11th district of Paris

In October 1943, the so-called “de-naturalization commission”, which had reviewed Moïse Bercovici’s French citizenship, ruled in favor of keeping him “as part of the French community”. The family no doubt felt more secure as a result. Moïse, Salomon and Niche remained French citizens.

Arrest and deportation

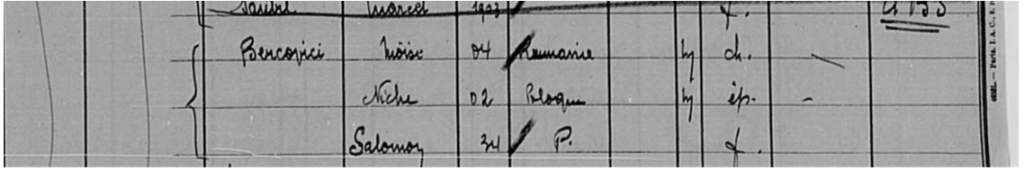

Salomon and Niche were arrested on July 15, 1944. We know nothing about the circumstances in which it happened but it was most likely at their home. In the police register, they were listed on the same line as having arrived together as mother at 12 noon.

A 3pm on July 17, 1944, Niche et Salomon left the police department and were taken to Drancy camp, where they were interned. The Drancy search log reveals that when she arrived, Niche had 424 French francs on her, which were confiscated.

They were held in Drancy for nearly two weeks. It was very hot in Paris that July, and the sanitary conditions in the camp were atrocious.

On July 31, 1944, just three weeks before Paris was liberated, Niche and Salomon were deported to Auschwitz on Convoy 77, which was the last of the large transports from Drancy.

As soon as they arrived in Auschwitz, they were sent the gas chambers. The date on which they were later declared to have died was August 5, 1944.

Things about which we can only speculate…

There is no record to this day of what happened to Moïse or if he was deported. His name is not listed in the Shoah Memorial archives. He might well have joined the Resistance. As for his first son, Samuel, he too appears to have avoided deportation.

This was also the case for Ruth Zylberman and Georges Perec[16].

During French class, the students read passages from Georges Perec’s Tentative d’épuisement d’un lieu parisien (Attempt to wear down a place in Paris), Ruth Zylberman’s 209 rue Saint Maur and Patrick Modiano’s book about Dora Bruder[17], in order to explore the process of investigating and writing about historical places and archived records. How is it possible to reconstruct the life of someone about whom all that remains are a few administrative records and some details about places they lived or worked? With a little historical knowledge about the context, such clues serve as the source of speculation and help to fuel the imagination. Detailed analysis of the buildings and addresses where the Convoy 77 deportees lived provided the students with the starting point for an initial attempt at writing in the style of Ruth Zylberman, while the historical records were used to write biographical profiles.

18, passage Gustave Lepeu

Off Boulevard Voltaire, near the Charonne subway station, there’s a little street called Cité de Phalsbourg. At the end, it crosses Rue Léon-Frot and becomes the Passage Gustave Lepeu.

Near the Passage, in rue Léon-Frot, there’s a bakery, two grocery stores, two bookshops (one of which specializes in comics), a restaurant with a dance floor, a Japanese restaurant, an Italian delicatessen, an Asian restaurant, a French restaurant, a café, two bars, a synagogue, and just a few yards further on is the Père Lachaise Cemetery.

There are restaurants on either side of the entrance to the Passage, which is paved and planted with trees. Along the length of the apartment buildings, there are large plants in pots of different various designs. The buildings themselves are quite narrow and not very tall.

No. 18 Passage Gustave Lepeu is nothing special. In fact, it’s quite a humble building. It has four floors. There are no balconies, no flowerpots, and no other decorative features. Next to it is a planter containing some bamboo and a few small shrubs. The number is painted brown. There are two gutters, one on either side of the door.

It is made up of two sections: the lower half is made of wood and the upper half of opaque glass, and there is a small tilt-and-turn window above it. The handle is broken on the outside, so all you have to do to get in is to push the door open.

The entrance hall is narrow. The ceiling lamp gives very little light. There are old mosaic tiles on the floor. The narrow staircase is made of wood, as is the banister. The whole place is run-down. There is nothing to suggest that almost 80 years ago, this building was Niche and Salomon Berkovici’s last refuge.

Hannah Tangy-Savoldelli, class 3e2

Notes

[1] – We referred to the biography on the French website Maitron of Moïse Berkovici, Niche’s husband and Salomon’s father. It was written by Daniel Grason, published online on April 28 2015 and last modified on May 5, 2015.

[2] – Girard Patrick. Jewish immigration. Hommes et Migrations, n°1114, Juillet-août-septembre 1988. L’immigration dans l’histoire nationale. pp. 49-56.

[3] – From the biography on the Maitron website, we discovered a little more about Moïse.

[4] – “11,000 Romanian Jews were living in Paris between the wars” op.cit. pp. 52.

[5] – “Of the 90,000 Jews in Paris, 45,000 came from Poland”. op.cit. page 52.

[6] – We also found Crenta spelled differently.

[7] – Crenta Idlik (née Harabagui) was born in Darabani, Romania in 1901. She was the daughter of Shimshon and Eidela Harabagui. She was a stamping machine operator[8] – In order to help foreigners integrate into French society, a decree enacted on August 10, 1927 facilitated access to French nationality (the residence requirement was reduced to 3 years). From 1927 to 1938, the number of people granted French citizenship averaged 38,000 a year, rising to 81,000 in 1938.

[9]– ADP D2M8 397: Out of a total of 44 residents in a hotel, half were foreigners.

[10]– 1936 census, ADP D2M8 704.

[11] – According to the biograpy on the Maitron website: “He left along with 1,200 volunteers from the Paris area and northern France for Barcelona. A noncommissioned officer by profession, he was posted to the 13th Brigade of the 1st Franco-Belgian Company at Villastar in the Teruel section in Aragon.

[12] – https://maitron.fr/spip.php?article172643

[13] – We did not find his name on the list of children deported from the 20th district of Paris. He only appears on the list of children deported from the 11th district.

[14] – which defined the term “Jewish race” as used by the Vichy government and which excluded Jews from working in the civil service, the press, the cinema and the medical professions…

[15] – April 26, 1941

[16] – “209 rue Saint-Maur Paris Xe autobiographie d’un immeubles”, “209 rue Saint-Maur, Paris 10th district, autobiography of a building”, by Ruth Zylberman, published by Le Seuil, 2019.

“Tentative d’épuisement d’un lieu parisien”, “An attempt to wear down a place in Paris”, by Georges Perec, P.O.L, 1975.

[17] – “Dora Bruder”, by Patrick Modiano, Gallimard, 2012.

Français

Français Polski

Polski