Samuel Barouh (1925-1944)

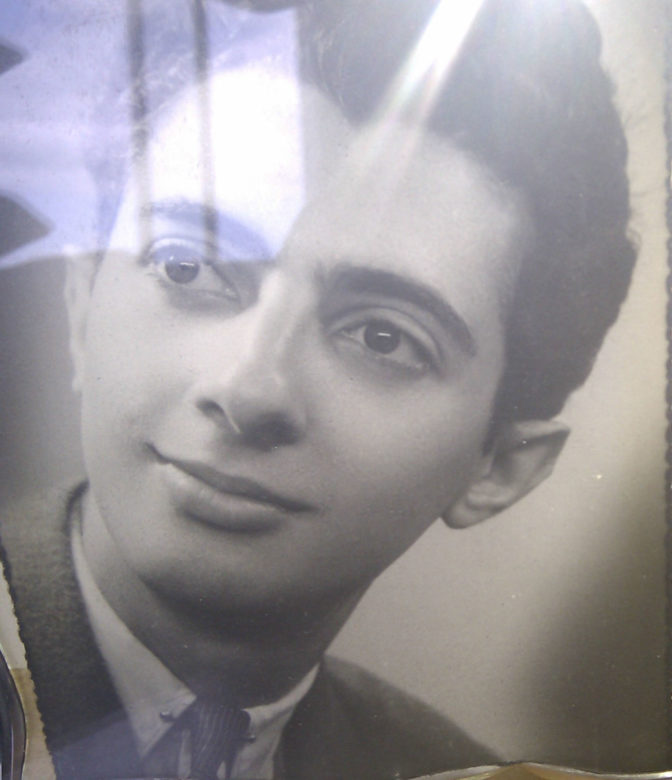

Photo of Samuel Barouh at about 17 years old (Barouh family archives)

(Click on the images to view them in their original format)

Why did we decide to research the life of this deportee?

- He was born in Versailles, so it was easy to go to the departmental archive service in Saint-Quentin-en-Yvelines to view the civil status registers, since our school is not far from there.

- His story is unusual compared to that of some of the other Convoy 77 deportees.

- His address in Perpignan: what did he go there for, when he was born in the Paris area?

- He was arrested in Compiègne: In 1944, Compiègne-Royallieu was an internment camp for resistance fighters. Might Samuel have been a member of the Resistance?

- Another Convoy 77 deportee, Bernard Tonningen, also lived in Perpignan and he too was arrested Compiègne. Did they something in common?

- His age. Samuel was 19 years old when he was deported, barely any older than us.

- The fact that almost nothing was known about him. We felt that we couldn’t just abandon him…

Samuel Barouh at around 18 years old (Barouh family archives)

Samuel Barouh at around 18 years old (Barouh family archives)

I- A well cared-for child in the Paris suburbs

“On Wednesday, June 24, 1925, at 5 p.m., at 94 rue de la Paroisse, in Versailles, was born Samuel, Robert, of the male sex, to Léon Barouh, a commercial traveler, born in Marseille on July 8, 1889, and Djoya Bensignor, his wife, not working, born in Aïdine (Turkey) in the year 1891…”

Thus begins Samuel’s birth certificate 1…

(the notes in numbers refer to sources, while the notes in letters are links)

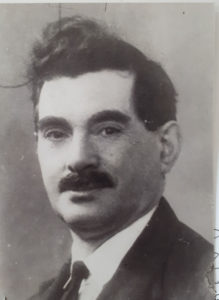

Samuel’s father, Léon Barouh :

Léon Barouh, Samuel’s father (Barouh family archives)

Léon Barouh was born on July 8, 1889 in Marseille. He was the son of Bension Barouh, who was 27 years old and was a merchant, and Houssi Benjacar/Lucie Beniaca, who was 24 years old and was not working at the time.2

In the military recruitment registers (1887-1921), in the Paris Archives, we found Léon Barouh, class of 1914, registration number 2279. He was 5’6” tall and had distinctive features such as an “extensive abdominal scar” and “supernumerary toes”.

He was drafted into the 26th Infantry Regiment during the First World War and took part in the fighting as a private from November 26, 1914 to December 15, 1914. He was discharged on health grounds, since he had “chronic nephritis and eventration”.

He worked as a peddler of fashion garments and later as a travelling salesman and fairground merchant.

We know that in 1922, Bension and Lucie Barouh, Samuel’s grandparents-to-be, lived at 2 rue Pache in the 11th district of Paris.3

His mother, Djoya (Judith) Bensignor:

Djoya Bensignor was born in Aydin in Turkey, then in the Ottoman Empire, in 1891.

She most likely arrived in France in 1920, with her brother Haïm and her mother, Zimboul Houly. Her father, Chemouel (Samuel) Bensignor, had probably died before they moved, because when Djoya got married in 1922, the word “deceased” was written beside his name on the marriage certificate.

The set up home at 71 rue de la Paroisse in Versailles, near Djoya’s other brothers, who had moved to France earlier on. They were:

– Isaac Bensignor, who lived with his family at 9 bis rue Montbauron, in Versailles, and then as from 1921 in Viroflay. 4

– Maurice Bensignor, who came to join his brother Isaac. They earned their living as fairground merchants selling fabric at the Clignancourt flea market and other suburban markets, before opening their own hosiery and glove store in 1921 at 104 rue d’Aboukir in the 2nd arrondissement of Paris, thereby founding the company Bensignor Frères (Bensignor Brothers). b

Maurice and his wife Rachel Houly had three children born, all born in Versailles: Sam, born in 1921, Reine, born on July 3, 1923, and Janine, born on October 18, 1926. Maurice’s family lived in Versailles, at 12 boulevard de la République (this was their address in 1944 when they were arrested).

– In 1926, Vida Benyacar née Bensignor, Djoya’s widowed sister, also came from Turkey to settle in Versailles with her 6 children, including Sadia and Joseph, who we will come back to later on.5

Léon Barouh and Djoya Bensignor were married in Versailles on July 13, 1922. Haïm Bensignor and Lucie Gilbert, Isaac Bensignor’s wife, were the witnesses. 3

They lived at 94 rue de la Paroisse, where Samuel was born on June 24, 1925.

In the 1926 census, the Barouh family was still living at the same address.

On March 9, 1931, another child, Jacques, arrived. By then the family was living in the 3rd district of Paris, in the Marais, at 30 rue Notre-Dame de Nazareth a.

Samuel’s childhood was shaped by the fact that he belonged to such a close-knit family, where the influence of his uncles, Maurice in particular, and of his aunts and cousins, was clearly important and remained so during the war.

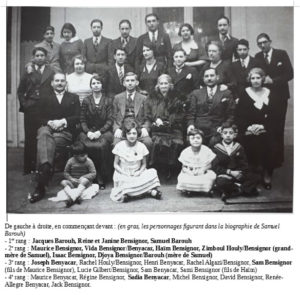

1934 was a high point in the life of the family when Sam, Maurice’s son, had his Bar Mitzvah, which brought the entire Bensignor family together in Versailles.

Samuel was 9 years old at the time.

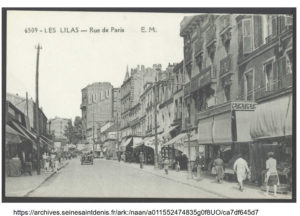

The family then moved to 198 rue de Paris in Les Lilas, most likely in 1936. In fact, the Barouhs were no longer living in Paris at the time of the 1936 Paris census and they were not yet living in Les Lilas at the time of the 1936 census there. In 1937, Léon Barouh was registered on the Les Lilas electoral roll as number 203. He had entered “novelty merchant” in the occupation section of the registration form. 6

The rue de Paris in Les Lilas

They became neighbors with Haïm (Henri) Benyacar, one of Vida’s sons, who lived at number 163 on the same street with his wife Mathilde (Les Lilas census 1936). Vida joined them a little later5, or at least during the war, until she left to be near her daughter in Bagnolet.

We know from their family memories that Samuel and his brother Jacques, like all the other children in the neighborhood, went to play in the grounds of Fort Romainville, which was not far from their home.

II- War broke out and the family members went their separate ways

When war broke out in 1939, the family sent Samuel to Arcachon, on the coast of south west France, to keep him safe. He went to the Condorcet school, which specialized in vocational courses. He enrolled in the business section and began in the second year of the program. The school principal, Jean-Camille Duthu, stated in a report he wrote on September 28, 1940, that Samuel was a good student and very well behaved. In 1940, Samuel passed a French “CAP”, a vocational training certificate, in accounting.7

After the roundup in Paris on August 20, 1941, which led to the opening of the Drancy camp, several of Samuel’s cousins also fled Paris, including Sadia Benyacar, who left with his wife Hélène and his son Michel and went to live in Perpignan. 8

In December 1941, Samuel’s uncles, Maurice and Isaac, had their property confiscated. Their stores (the one in Paris and another that they had bought in 1940 at 2 place du Pilori in Château-Gontier in the Mayenne department) were seized and sold off. The sale was recognized by the General Commissariat for Jewish Affairs in June 1942. Isaac took refuge in Lyon with his family. 4

Following his year in Arcachon, after the June 1940 armistice, Samuel moved back to Les Lilas. We know that during the school year 1941-1942, he studied at the Ecole Supérieure de Commerce, a leading business school in Paris located at 79 avenue de la République). Samuel, who went by the name of Samy, was in 9th grade in the “A” class. His school report describes him as a good student who was “intelligent and hard-working” in mathematics, who had “a very keen interest in the physical sciences” according to his teachers. However, he worked less hard in the humanities and had little interest in law. Physical education was not his strong point either: he was criticized for his lack of energy and poor attendance! At the end of the second term, the principal deemed his “conduct unsatisfactory, must be improved as of now”, and several teachers reported his lack of attention in class!

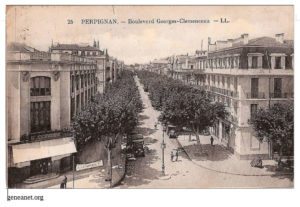

But then Samuel left Les Lilas. “In 1942, my parents smuggled Samuel into the free zone. He went to live in Perpignan, at 46 boulevard Georges Clemenceau, where we had family,” wrote Jacques Barouh in 2001 9. We believe that Samuel crossed the demarcation line separating the occupied zone in the north of France from the non-occupied zone in the south in summer or fall of 1942, between the end of the school year in late June and November, when the Germans also occupied southern France. It would appear that Samuel crossed the line near Bourges10, probably with the help of a smuggler, as his brother Jacques suggested in his testimony.

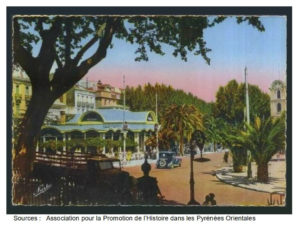

Boulevard Georges Clemenceau in Perpignan

III- Samuel’s time in Perpignan

Samuel went to stay with Robert Houly (a brother-in-law of Maurice Bensignor, Samuel’s uncle) and his wife Jeannette, at 46 boulevard Clemenceau in Perpignan.7

We know about his time in Perpignan through some letters that he signed with his middle name, Robert, which his family has kept. They are addressed to his parents and to his little brother, who he fondly calls Jacquot or Jacky. There are ten letters that we know of, each two to four pages long, written between August 9, 1943 and May 30, 1944. 7

Samuel, who hoped to become a chartered accountant after the war, found work as an accountant in Perpignan:

“In my last letter, I told you that I was going to leave my job at the insurance office and start working for the Société Marseillaise de Crédit. As of August 3, I have.” (Letter dated August 9, 1943)

We can see right away from his letters that food was his primary concern, because it was both expensive and rationed in the days of the German occupation. He does not even try to hide the fact that he rarely had enough to eat.

“I go to two restaurants at midday to fill me up (…) I eat about 2 pounds of fruit a day” (Letter dated August 9, 1943).

“I eat nearly two loaves of bread a day, at 70 francs a kilogram.” (Letter dated May 30, 1944)

“You have to race to the gardens (…) to be able to get a few vegetables (…) As for vegetables, since they are not available on the market in Perpignan (not even tomatoes), I will tell Sadia to send you a parcel from Ille.” (Letter dated September 1, 1943)

Samuel was very close to his family and often asked for news of his parents and his brother who had stayed in Les Lilas. He also corresponded with his uncle Maurice, his aunt Vida and various cousins. In his letters to his family members in Les Lilas, he complained that they did not write to him often enough. One can sense how much he was missing his family:

“I can’t wait to see you again.“ (Letter dated August 27, 1943)

“My dear little Jacquot, what are you up to during vacation? (Letter dated 6 September 1943).

Yet his parents also complained that he didn’t write to them often enough! He then promised to write to them twice a week (Letter dated September 1, 1943).

Samuel was happy that he was able to send his family in Paris crates of fruit and vegetables to help them have enough to eat. These did not always arrive at their destination, however: “I am very surprised that you did not receive the crate of pears and eggplant.” (Letter dated August 12, 1943).

For their part, his parents sent him undershirts knitted by his Mom, shoe coupons and a few books, including logarithm tables (Letter dated October 20, 1943)

With his salary of just 1300 francs a month, “which is not the highest“, Samuel was supported financially by his parents, who sent him 1000 francs a month. He spent about 2700 francs a month so he had to use up all of the small sum that his parents sent him. Samuel explained in his letter dated August 9, 1943, that other young people with similar financial problems also got by either with the help of their parents or by getting involved in the black market, which he was loath to do.

Nevertheless, we understand from Samuel’s replies that his parents often criticized him for spending too much, for throwing money down the drain, and for thinking only of having a good time, such as going to “surprise parties” that cost 200 francs! This was something that Samuel firmly denied.

HIs letter dated September 1, 1943 describes his routine: “Here are my working hours: 8am-12pm; 2am-7am; Saturday morning: 8am-1am”. Saturday afternoons were spent “cleaning and running various errands (laundry, grocery, butcher etc.)” and he said he had “no time to run around to places outside of town to try to find a few vegetables.”

He made the most of Sundays, and some evenings, to spend time with his friends. They went to the beach, to a movie once or went dancing at friends’ houses. He also mentioned a number of “surprise parties” that cost between 30 and 50 francs (Letter dated May 30, 1944). At Whitsun in 1944, Samuel said he was “invited with some buddies to a friend’s house 47 km (about 30 miles) from Perpignan” (Letter dated May 30)

He often saw his cousins Sadia Benyacar and his brother Jo, and went to celebrate the birthday of little Michel, the son of Sadia and Hélène Schochet, with the family on September 12, 1943. He also had a visit from his cousins Reine and Janine Bensignor who came all the way from Paris to see him.

As far as travel was concerned, Samuel went on vacation in July 1943 to Formiguères, in the Pyrenees. He hoped to go back to Paris at the start of 1944 to wish his family a happy new year. (Letter dated September 6, 1943). He also announced that he was going to spend a few days with Jo in Limoges during the first two weeks of May 1944. (Letter dated April 24, 1944)

Samuel seems to have been in good health. He complained only about a callus on his left heel. He also revealed in his letter dated May 30, 1944 that he had spent about six weeks in hospital in September-October 1943 with a wound in his leg that would not heal. He said he was grateful to Dora, Jo’s wife, and Helene for coming to the hospital to bring him extra food.

On September 6, 1943, Paris was bombed and Samuel wrote his family about how worried he was. “Be careful, and after each of these bombings, please send me an update so that I know you are safe”. (Letter dated 6 September 1943)

During the night of April 21 to 22, 1944, the capital was bombed again, in particular the Barbès and Les Lilas districts, and Samuel became anxious yet again. “I have just heard about the latest bombing in Paris (…) The telegram Sadia received reassured us that you were in good health (…) Can you not get out of Paris?” (Letter dated April 24, 1944)

In his letter dated May 30, Samuel reiterated his hope that his mother and brother would come to Perpignan, and Maurice’s family too. He was concerned because he had not heard from him (Maurice and his two daughters had in fact been arrested on May 27, 1944, as a result of a tip-off).

IV- The arrests

The end of 1943 saw large-scale roundups of Jews in Perpignan, in particular in November.c In 1944, the atmosphere in Perpignan became increasingly tense and the Germans seemed to be growing ever more nervous, most likely because they knew that an Allied landing was imminent, although they did not know where it would be.

The news in Les Lilas was not good either, as Jacques explained:

“On April 24, 1944, my father Léon Barouh did not come home from work in the evening. An alarm sounded; my mother and I went to take shelter in the hallways of the “Mairie des Lilas” subway station.

When the alert was over, my mother decided that we should go and spend the night with her sister, Vida Benyacar, who was staying with her daughter, Mrs. Habiff, at 224 rue de Noisy Le Sec in Bagnolet.

The following day, we learned that the police had come looking for us that morning, accompanied by my father Léon.” 9

We can therefore understand how Samuel, upset by the “accident” that had befallen his father, also dreaded what he called “the great departure”. In his letter dated May 30, 1944, he explained that he left the bank and that in mid-May 1944 he had taken part in a census of young people (we think this was for the Service du travail obligatoire, or Compulsory Work Service), in the hope of avoiding being deported.

He said he was then “hired by a German company“, and “worked with a shovel from 6:45 a.m. to 6:00 p.m. with half an hour for lunch on the site”. Might this have been a construction site for blockhouses and other coastal fortifications in the area around Perpignan, such as the blockhouse at Torreilles?

Samuel’s arrest

According to the family memories, as transcribed by Jacques Barouh 9, Samuel was arrested on May 15, 1944. This is confirmed by several records, although they contradict each other to some extent: 11

– first of all, the “Application made in order to have the civil status of a “non-returnee” made official”, dated December 9, 1946, reads “Caught in May 1944 in Perpignan for acts of Resistance and went from Compiègne to Drancy”.

Deportation cars at the railroad station in Compiègne (Photo taken by Pierre Guieysse, 2020)

– then the “Request for the granting of the status of political deportee” dated January 11, 1952, states that the French made the arrest on May 15, 1944 in Perpignan and that he was “arrested as a Jew during a round-up”. This same record also states that Samuel was sent from Drancy to Dachau…

The status of “political deportee” (card no. 1.1.75.00521) was finally granted to Samuel on July 20, 1953, taking into account a period of internment from May 15, 1944 to July 30, 1944 and a period of deportation from July 31 to August 5, 1944, the date on which convoy 77 was likely to have arrived in Auschwitz.

However, the date of May 15, 1944 is implausible. Several factors seem to support this:

- Samuel’s letter of May 30 was written by a young man who was still free, even though he was working on a German construction site. He stated that he celebrated Whitsun, which was on May 28 in 1944, with his friends.

- A letter from the Prefect of the Pyrénées-Orientales department to the Ministry of Veterans’ Affairs and Victims of War on rue de Bercy in Paris, dated October 8, 1952, states that “Mr. Samuel Barouh, born on June 24, 1925 in Versailles, who was arrested in Perpignan in May 1944, is unknown to the departmental archives of the General Intelligence agency and to the Central Police Commissioner. No information relating to this arrest has been collected.”11

- We know that Sadia Benyacar was arrested on June 6, 1944, together with his family, following the “arrest of one of her cousins, Robert Barouch”. 8 This is confirmed in the testimony of Henri Schochet12, Sadia’s brother-in-law, who explained that Sadia and his family had to leave their home on rue Pierre Lefranc in Perpignan in a hurry. They then took refuge in rue Victor Hugo in Ille-sur-Têt, where they arrived on June 3. 13

The time between Samuel’s arrest and the date on which the Benyacars moved was clearly very short.

- We therefore believe that Samuel was arrested on June 1 or 2, 1944. We also know that the Gestapo arrested Bernard Tonningen in Perpignan on June 2, on the grounds that he was involved in the Resistance 14.

According to Henri Schochet 12, Samuel was a member of the Resistance and of the FTP (Francs-tireurs et Partisans, an armed resistance organization created by leaders of the French Communist Party). And according to the Barouh family’s memories, we know that “Jeannette Houly’s daughter remembers that her mother often cautioned Samuel and asked him to be very careful, but gave no further details”, Alain Barouh, Jacques’ son, told us. This corroborates the fact that he was a member of the Resistance, but we don’t know any more than that.

Henri Schochet also described how Samuel, an elegant young man of 5’10” with a “zazou” look about him, often went to the Palmarium, which was 300 yards from where he lived. This was a well-known dance hall in Perpignan, frequented at the time by men from the Militia, Germans from the nearby Kommandantur and some other shady characters, including Nessim Eskenazi. This Eskenazi was a stateless Jew who worked at the Castillet cinema, not far from the Palmarium, and who, in order to make himself look good in the eyes of the Germans, acted as an informer for them. (He is best known for having turned in a group of Resistance fighters from the Valmanya maquis to the Germans in August 1944. This led, among other things, to his being shot by firing squad in November 1944)15. Mr. Parrilla, a local historian from Ille-sur-Têt, believes that he was the one who set up and manipulated the young Samuel, who was somewhat naïve and foolhardy to go to the Palmarium when he was involved in the Resistance.

On June 2, 1944, Samuel was taken to the Gestapo headquarters on avenue de la Gare in Perpignan, where he was tortured mercilessly.

Under torture, he talked… He gave Sadia’s name to the Germans.

Sadia was in the Resistance, in association with the Secret Army and the FTPF, for whom he distributed pamphlets and clandestine newsletters. He belonged to the Ponts-et-Chaussées network. However, according to Henri Schochet, Samuel did not know about that. Sadia was arrested as a Jew rather than as a member of the Resistance, together with his family and Henri Schochet.

Samuel was then imprisoned at the Citadelle in Perpignan, which is where Henri Schochet spotted him.

June 12, 1944: Bernard Tonningen was transferred by train from Perpignan to the Compiegne camp14, most likely together with Samuel. Did they already know each other?

The Compiègne camp (photo Pierre Guieysse, 2020)

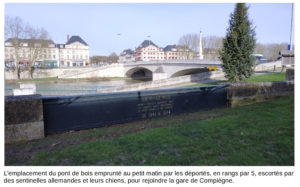

Compiègne, the former “deportees’ bridge” (photo Pierre Guieysse, 2020)

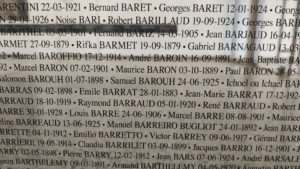

Very little is known about the Compiègne-Royallieu camp at that time, since the camp records were destroyed by the Germans. We are sure that he spent time there, because his name is included in the list of internees at the entrance of the Compiègne-Royallieu Memorial.

Compiègne, part of the Wall of Names

July 6, 1944: Samuel and Bernard Tonningen arrrived in Drancy camp.16, 14

July 31, 1944: Convoy n°77 left Drancy for Auschwitz

August 3, 1944, during the night: The convoy arrived in Auschwitz after a four-day journey in appalling conditions on one of the so-called “death trains”.

We can only imagine that Samuel was in terrible physical and psychological shape. He could hardly have recovered from the torture that he had undergone in Perpignan. The was probably why, unlike the other young men of his age, he was not sent to the labor camp barracks, as was Bernard Tonningen, for example.

Samuel, at only 19 years old, was taken straight to the gas chambers, along with the older and weaker people and the children. Unless, of course, he had already died on the train.

We had the opportunity during this project to learn about the ordeal suffered by the families of the deportees who died or disappeared. For example, eight years after the event, they still did not know what happened to Samuel, not even the date of his arrest, let alone his subsequent journey or eventual fate. After the war, a newspaper vendor in Les Lilas even told the family that she had seen Samuel in Romainville (although there is nothing to confirm this) 9.

An official missing person’s certificate was issued for Samuel on May 10, 1947 11. Then, on October 12, 1951, a death certificate was issued, which stated that he had died on July 31, 1944 in Drancy17. The family was unhappy about this, however, because they knew that Samuel had been sent to Auschwitz and they continued to hold out hope even when, in 1953, the words “Mort pour la France” (“Died for France”) were added to his death certificate.

Alain Barouh, Jacques’s son, remembers seeing his father break down in tears after receiving official confirmation of Samuel’s death… This was in the mid-1970s…

It was only on September 12, 2008, that Samuel was officially recognized as having “died during deportation on August 5, 1944 in Auschwitz rather than on July 31, 1944 in Drancy”.17

What became of them all?

– Léon Barouh, was arrested by the French police on April 24, 1944 and taken to Drancy, from where he was deported on May 15, 1944 on Convoy 73 18 . According to the family memories, Léon fell asleep in the subway, got off one stop too late, and as a result ended up in the midst of a round-up. Convoy 73, which was made up of men only, was the only one to go to the Baltic States: either to the Kaunas extermination camp in Lithuania or to the Reval (Tallinn) prison in Estonia. Simone Veil’s father and brother were also on this convoy. They never came back.

– After Léon was arrested, Djoya Barouh and Jacques were initially hidden by uncle Maurice, in Versailles. They then went to Château-Gontier in the Mayenne department, where they stayed with Louis Fleuroux and Marguerite Portier-Fleuroux d, the managers of the Bensignor brothers’ store. Both they and Azeline-Louise Portier (with whom Jacques and his mother, under the name of Madame Jeanne 9 stayed) were named Righteous Among the Nations in 2003 (case number 10096) by the French committee for Yad Vashem. In mid-May 1945, Djoya and Jacques returned to their home in Les Lilas.

– The uncle, Maurice Bensignor and his two daughters, Reine and Janine, were arrested on May 27, 1944 and deported to Auschwitz on June 30, 1944 on Convoy 76. Janine was murdered on arrival on July 5, 1944. Reine survived, returned to France in 1945 and married Henri Gerson, also a former deportee, before moving to the United States.

Sam, Maurice’s son, miraculously avoided being arrested because he was not at home at the time, and so did his mother Rachel.

Maurice’s son Sam Bensignor’s Bar Mitzva, 1934 (Barouh family archives)

Maurice died of pleurisy on January 3, 1945, in the Monowitz camp, which was annexed to Auschwitz, where the IG-Farben synthetic rubber factory was located.19

– Sadia’s family was also deported on Convoy 76: Hélène and Michel were killed in the gas chambers soon as they arrived at Auschwitz. Sadia was sent to Monowitz, along with his brother Maurice (Moïse) Benyacar, who was also on Convoy 76. In the bitter cold of January 1945, they were forced to leave Auschwitz on foot on the so-called death marches, and were then put in open wagons on a train to Buchenwald. Sadia died of dysentery. Maurice survived and returned to France.8

– The aunt, Vida Benyacar née Bensignor, was deported on Convoy 77 and was killed on arrival in Auschwitz.5

– Bernard Tonningen, who was born on 25 October 1899 in Amsterdam, arrived in Auschwitz on 3 August 1944 on Convoy. 77. He was assigned to a kommando that carried out earth-moving work.

“Towards the end of October 1944, there was a “commission” during which men’s names were drawn at random. Bernard Tonningen was among them. This drawing of lots was to decide who was to be sent to the crematorium ovens. I watched them leave in a truck and a short time later the truck came back with their uniforms… but without the men,” recalled Hugo Perez, who was also prisoner at Auschwitz.14

– The uncle Isaac Bensignor was apparently murdered on August 23, 1944 in the basement of the Lyon Gestapo headquarters, having been reported by his secretary, who was the mistress of a Gestapo agent. 4

The biography of Samuel Barouh was featured during the Open Day at the René Descartes middle school in Fontenay-le-Fleury in March 2022, and then during the May 8 Remembrance Day ceremony at the Fontenay town hall.

On June 24, 2022, in the presence of Samuel’s nephew, Alain Barouh, who represented the family, the Principal announced that the school would sponsor a memorial paving stone in the name of Samuel Barouh, which is to be installed in front of his last home, at 46 boulevard Clemenceau in Perpignan.

Thanks

Enormous thanks are due to Mr. Alain Barouh, who kindly agreed to help us by sharing the files of family memories that his father, Jacques Barouh, had so painstakingly collected and transcribed.

We would also like to thank the Guy Lemarchand Funeral Home in Les Sables d’Olonne, since without their help we would not have been able to find the Barouh family and accomplish our project.

Several historians helped us by providing us with copies of records and valuable information and we would like to thank them too:

– Mr. Jérôme Parrilla, the deputy mayor of Ille-sur-Têt and president of the nonprofit association “Pavés catalans de la Mémoire”

– Ms. Madeleine Souche of the l’Association pour la Promotion de l’Histoire dans les Pyrénées Orientales (Association for the Promotion of History in the Eastern Pyrenees)

– Mr. André Jerosolimski of the nonprofit association “Racines du 93”

We are grateful to the Victims of Contemporary Conflicts Archives Division in Caen, who agreed to send us copies of the files on Samuel Barouh and Bernard Tonningen, during the Covid epidemic in 2020.

Lastly, we would like to thank Ms. Fieux, the Principal of Descartes middle school in Fontenay-le-Fleury, for her support for this project and for sponsoring the paving stone in memory of Samuel, which is a source of solace for the Barouh family and indeed for us.

Sources:

- Register of births in Versailles in 1925, Yvelines departmental archives

- Léon Barouh’s birth certificate, Bouches-du-Rhône departmental archives

- Register of marriages in Versailles in 1922, Léon Barouh and Djoya Bensignor’s marriage certificate dated July 13, 1922, Yvelines departmental archives

- Fiche Bensignor Isaac, Maitron

- Biographical note on Vida Beniacar, Convoi 77

- The Les Lilas electoral roll, 1937, Seine-Saint-Denis archives

- Barouh family archives

- Biographical note on Sadia Benyacar’s family, Convoy 76, Cercle d’Étude de la Déportation et de la Shoah

- Excerpts from the testimony that Jacques Barouh wrote in 2001 to the French Committee for Yad Vashem regarding a request to award the Medal of the Righteous to Mr. and Mrs. Fleuroux of Château-Gontier, Barouh family archives

- Map showing a place of residence during the war near Bourges, on the Yad Vashem webpage for Samuel Baroch

- File on Samuel Barouh [21 P 421 440], Victims of Contemporary Conflicts Archives Division of the Ministry of Defense Historical Service, in Caen.

- Interview with Mr. Henri Schochet, October 25 1996 in Mandelieu, Survivors of the Shoah, the French Audiovisual History Foundation. Vidéo

- Kindly sent by Mr. Jérôme Parrilla

- File on Bernard Tonningen [21 P 544 464], Victims of Contemporary Conflicts Archives Division of the Ministry of Defense Historical Service, in Caen

- Nouveau dictionnaire de biographies roussillonnaises, edited by Gérard Bonet, 2011. Article about Eskenazi Nessim.

- Drancy camp record regarding Samuel Barouh, Shoah Memorial in Paris

- Samuel’s death certificate, Les Lilas town hall

- Drancy camp record regarding Léon Barouh, Shoah Memorial in Paris

- Biographical note on Maurice Bensignor’s family, Convoy 76, Cercle d’Étude de la Déportation et de la Shoah

Links:

a – http://archives.paris.fr/arkotheque/visionneuse/visionneuse.php?arko=YTo0OntzOjQ6ImRhdGUiO3M6MTA6IjIwMTktMDUtMTEiO3M6MTA6InR5cGVfZm9uZHMiO3M6MTE6ImFya29fc2VyaWVsIjtzOjQ6InJlZjEiO2k6MTc7czo0OiJyZWYyIjtpOjE2OTgwMDg7fQ%3D%3D#uielem_move=0%2C0&uielem_islocked=0&uielem_zoom=31&uielem_brightness=0&uielem_contrast=0&uielem_isinverted=0&uielem_rotate=F

b – https://www.ajpn.org/juste-Marguerite-Fleuroux-1091.html

c – https://www.lasemaineduroussillon.com/2020/06/26/perpignan-le-temps-des-rafles/

d – https://www.francebleu.fr/infos/culture-loisirs/une-premiere-en-mediterranee-le-blockhaus-de-torreilles-inscrit-aux-monuments-historiques-1555348668

“Guillem Castellvi recalls that these fortifications [such as the blockhouse in Torreilles] were built with shovels and pickaxes by inhabitants requisitioned as part of the Compulsory Labor Service. At 86 years old, Maurice Rabat recalled: “I was only 11 years old [so in 1944] but I know that every day about twenty people from Torreilles had to report to the village square” “ (excerpt from an article dated Monday, April 15, 2019)

Français

Français Polski

Polski