Sigismond BLOCH

Photograph taken from the application for the status of political deportee

This biography is the outcome of a collaborative effort between the Zespół Szkół high school in Stalowa Wola, Poland, and the Saint-Germain de Charonne middle school in Paris, France. The Polish high school is right next to where Sigismond Bloch was born and the school in Paris is near the cemetery where he is buried.

Two Polish high school students, Jan and Julia, and their librarian/teacher, Beata Traz, worked remotely with the 9th grade class 3b Germaine Tillion from Paris and their teacher, Danielle Artur.

Julia: I decided to take part in the project because I am interested in history. In addition, the idea of researching and discovering Sigmund Bloch’s life story, searching for clues and following his trail is also very appealing and is related to criminology, which I am thinking of as a future career. Recently, I have also become more interested in Jewish culture, and this project has enabled me to expand my knowledge in this area.

Jan: What made me decide to participate in the Convoy 77 project was the opportunity to be involved in writing biographies of people. I am very interested in history, and am always glad to learn more about historical events. I have to admit however, that despite the fact that so many years have passed and there are fewer witnesses to the tragedy that was the Nazi Holocaust, this period of history still arouses negative emotions in me. That is why I feel a need know more about it and to pass on this information to future generations.

In order to read the documents in the biography more easily, right-click and then click on “Open Image in New Tab”.

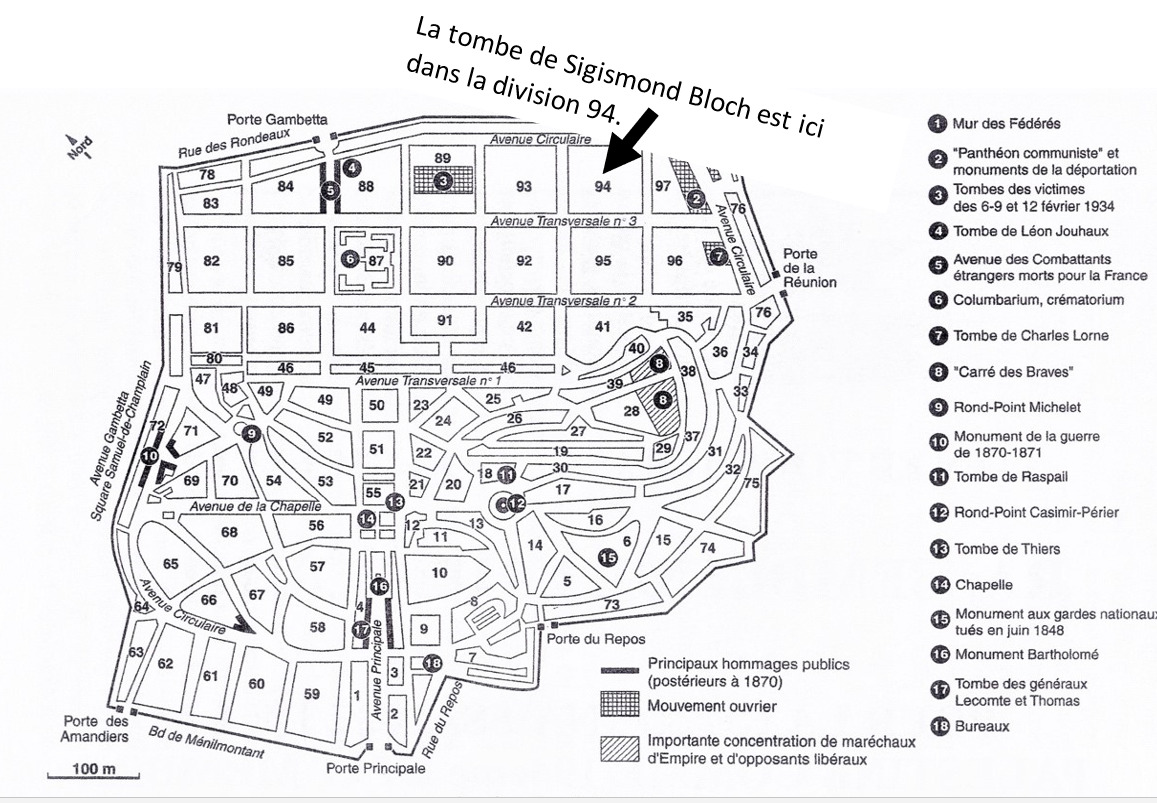

A grave in the Père-Lachaise Cemetery in Paris

The Parisian students began by studying the documents available on the Internet.

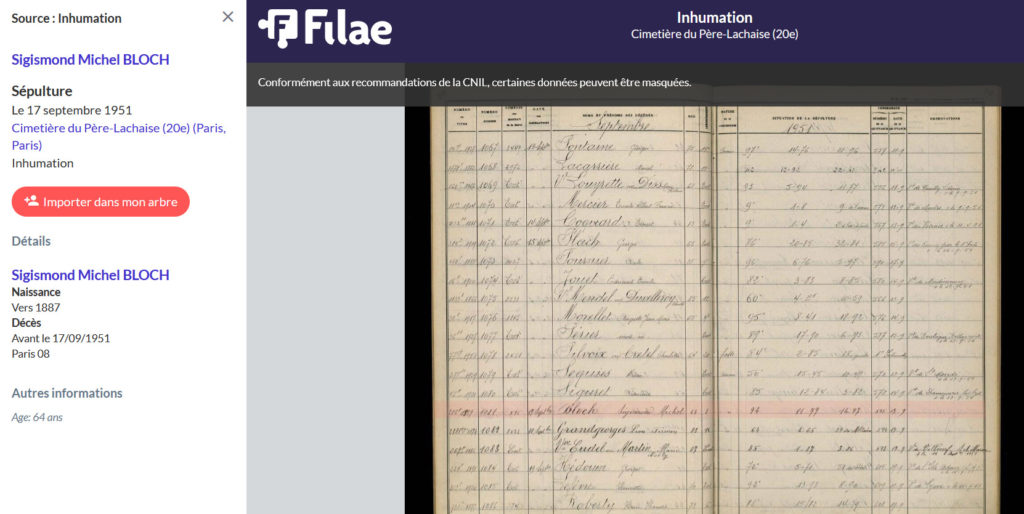

On the FILAE genealogical research website, it says that Sigismond Bloch was buried in the Père Lachaise cemetery.

Here is an excerpt from the email we sent to the service responsible for locating graves in the Père Lachaise cemetery:

“Hello, as part of the research for the European project Convoy 77 in memory of the victims of the Holocaust, I am looking for the grave of Sigismond Michel Bloch, who is buried in the Père Lachaise cemetery. He was born on January 8, 1887 in Tarnobrzeg, Poland. …… Please could you tell me whereabouts his grave is located?”

Here is the reply we received from the staff at the Père Lachaise cemetery, which is just along the road from the school and its students:

“I am writing to inform you that Mr. BLOCH Sigismond, Michel was buried on September 17, 1951 in the Père Lachaise cemetery in plot n° 206 PA 1929, which he himself bought. This gravesite is located in the 94th division; count 11 lines of graves from division 77, then 14 graves from division 97. In order to plan your visit in advance, I recommend that you download the map of the Père Lachaise cemetery from the website https://www.paris.fr/perelachaise.”

This is a photo of a plan of the cemetery. Sigismond Bloch’s wife, Augustine Thérèse Jouanneau, is also buried there. She died in 1965.

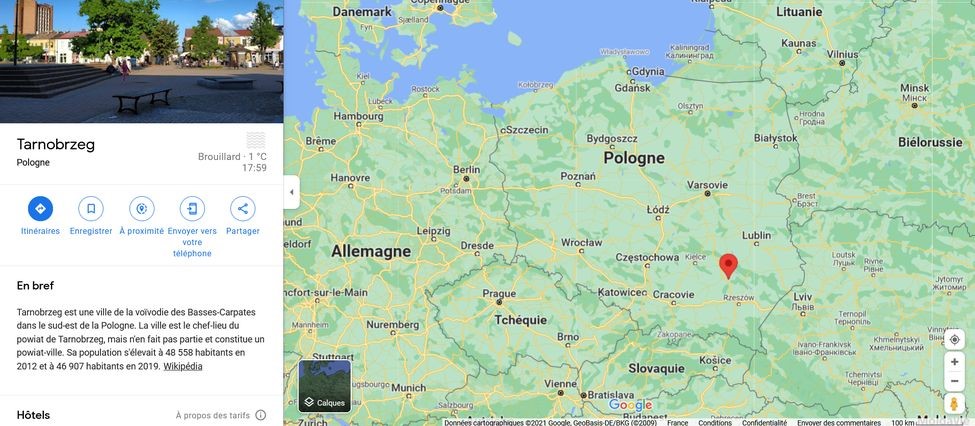

Sigismond Bloch was born in Tarnobrzeg, in eastern Poland

Tarnobrzeg is not far from Jan and Julia’s high school in Stalowa Wola:

Jan and Julia researched Sigismond Bloch’s birthplace and the historical background of the town:

The coat of arms and flag of the town of Tarnobrzeg, which was founded in the 16th century.

The situation of the Jews in Poland

The situation of the Jews in Poland during the First World War

The outbreak of World War I took the Jews of middle Europe by surprise and left them in a difficult position. They did not regard any of the warring nations as their enemies. They had no borders to defend. They were not interested in armed conflicts and saw no need for them, yet they became a part of them and were among the populations most affected by them. World War I was a turning point in recent Jewish history. It led to the erosion of liberal attitudes. In Eastern Europe, fighting took place in areas where the Jewish population lived, which in turn resulted in economic ruin for them. Resentment against the Jews intensified, and the economic foundation of the shtetls was undermined. About half of them ended up in the then USSR, where they were forced to adapt to the new culture. The other half were “transferred” as a result of the war from multinational states to newly established nation-states with predominantly nationalist populations.

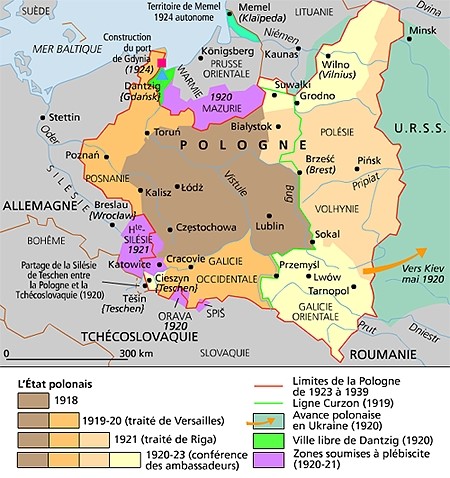

In 1918, Poland was re-established as a country and became independent again. The Jews once again found themselves in a difficult situation. They had to start all over again. For several years after the war, the political situation was unclear and the economic climate was very tough. The Polish army, central government and public authorities placed large orders, mainly with Polish industrialists, and employed mainly Poles. This left the Jews with no choice but to submit, emigrate or rebel.

The period between the wars

At the beginning of World War II, Poland was home to the largest concentration of Jews in Europe. According to the last pre-war census, in 1931, 3,130,581 Polish citizens declared themselves to be Jewish.

The 1931 census also showed that 77% of Jews lived in towns and cities, and only 23% in the countryside. This pattern did not change much until the outbreak of World War II. This became significant during of the occupation: the fact that the Jewish population was concentrated in urban and metropolitan areas made it easier for the Germans to discriminate against them and ultimately to exterminate them. Polish Jews felt deeply about their country. This is illustrated by the fact that about 85% of Polish Jews declared Yiddish or Hebrew as their mother tongue in the 1931 census. For the diaspora, Polish Judaism remained an infinite source of religious and moral values. The vast majority of Jews living in Poland since the time of their grandparents, as well as those who settled on Polish soil under the political and administrative pressure of the Russian Empire in the second half of the 19th century, maintained a distinct cultural identity. This was reflected in various ways, such as the everyday use of their common language, Yiddish, a distinctive dress code, and a tendency to live in a religious-national community somewhat isolated from the surrounding environment.

More than 55% of economically active Jews in Poland in the 1930s (other than those working in agriculture) were small craftsmen and tradesmen. These figures illustrate the rather humble status of the majority of Jews in Poland and their relatively insignificant representation among the elite. Of course, members of the Jewish intelligentsia, who were generally well integrated, took an active part in Polish social life. Hundreds of Jewish scholars, artists (both writers and visual artists), musicians, theatrical performers, and thousands of lawyers, economists, doctors, and engineers contributed significantly to the revival of the intellectual movement in the reborn Polish state after 1918, to the advancement of science and art, and to the rebuilding of economic life after a long period during which the Polish state did not exist.

Despite this, the Jewish masses were perceived by the majority of Polish society as being aloof and alienated. The attitude of the predominant Catholic Church in Poland towards the Jews was marked by mistrust, stereotypes and prejudices. The movement to promote Jewish-Christian dialogue was then in its infancy in Poland and was confined to small elite circles.

The attitude of Polish society towards the Jews between the wars

For many centuries, Poland was a country in which society tolerated exponents of religions other than Catholicism. This was enshrined, among other things, in the Warsaw Confederation of 1573, a document that safeguarded freedom of religion in the Polish-Lithuanian community. At the beginning of the 20th century, the situation began to deteriorate, as a certain section of society began to abuse followers of Judaism. In Poland, as well as in other countries, anti-Semitism, derived from both religious and moral sources, as well as from economic competition, increased sharply in the 1930s. This was reflected not only in the manifesto of the nationalist National Party and Christian Democrats, but also in the vociferous activism of the militant National-Radical Camp, which was banned after only a few weeks of existence in 1934 and which promoted a fascist agenda against ethnic minorities. Anti-Jewish offenses and incidents were objectionable, and indeed punishable, but the overall mood of public opinion was not good.

The Second World War

On September 1, 1939, the German troops invaded Poland. Ten days or so later, the Soviet Army joined the invasion, assisting the Germans. This was the beginning of the Second World War in Europe.

About 950,000 soldiers took part in the Polish campaign in September. More than 10% of them were Jews, which mirrored the percentage of Jews in the society of the Second Polish Republic. They served in various units, but mainly in the medical corps. They suffered the same fate as the other Polish soldiers; many of them were killed and wounded and tens of thousands were taken prisoner.

With the onset of the war came repression of the civilian population, especially the intelligentsia. It intensified following the September campaign, and became especially serious for the Jewish community. Restrictive racist legislation was introduced in the occupied territories. Deportation and confiscation operations began, and synagogues were deliberately destroyed. The initial decrees were enacted with the intention of isolating the Jewish population.

Starting in October, the first ghetto was created in Piotrków Trybunalski. At the beginning of December, all Jews over the age of 12 were ordered to wear a special sign on their clothing. In the General Government area (also known as the General Governorate for the Occupied Polish Region), this was a white armband with a blue Star of David worn on the right arm. In the territories annexed by the Reich, a yellow star was sewn onto clothing, on the chest and the back. However, no one at the time could have foreseen the enormity of the tragedy that would befall the Jews in the years that followed.

The town of Tarnobrzeg: History of the Jewish community in Tarnobrzeg

The first Jews appeared in Tarnobrzeg shortly after the town was founded in 1593. The fledgling town was attractive in commercial respects, having been granted the privilege of holding two fairs where grain was traded. It lacked skilled craftsmen, however. As a result, Jewish craftspeople moved in, as did several merchants who set up stores. In the second half of the 18th century, Jews held a prominent position in the town, as advisors and intermediaries of the town’s owners, the Tarnowskis.

At first, the Jews settled on the outskirts of the city. Over time, they moved to the market place, where they were traders. The Jews were almost exclusively responsible for commercial activity in the town. The town was very poor, as in around 1860, there were fewer than ten small stores in Tarnobrzeg, which operated out of wooden huts. In some of the stores, aside from what could be bought from the village peddlers, goods such as colored textiles, handkerchiefs, ribbons, household linen, caps, combs, tallow candles and pipes (which the peasants were very keen on at the time), were available. All this, except for the white linen bought from the peasants, was brought in carts from Tarnów, presumably sourced in industrialized countries such as Austria. A few other Jews traded in grain, which they sold by the sack, mainly on market days. Lastly, shortly before 1860, the first ironmonger’s store appeared. It sold iron to blacksmiths, as well as iron pots and pans, which were enameled on the inside. There were some inns, the most popular tavern being Josek’s, in the town hall. The first brick houses built in Tarnobrzeg belonged mainly to wealthy Jews. In 1914, Count Tarnowski also rebuilt the town hall in brick. There were also Jewish stores and a tavern. In addition to regular trading, the Jews were also involved in smuggling. They grew rich by transporting corn products and alcohol across the Vistula River from the Kingdom of Poland.

Between the wars, there was a branch of the Central Association of Jewish Craftsmen in Poland, which had about 100 members, based in Tarnobrzeg. In 1932, a People’s Banque was founded. In 1939, there was the Merchants’ Association, led by a man called Lejb Just, with 327 members. By then, there were about 3,800 Jews living in Tarnobrzeg.

After the first partition of Poland, Tarnobrzeg fell under Austrian rule and was part of the Kingdom of Western Galicia.

Soon after the outbreak of World War II, in mid-September 1939, the Nazi army arrived in Tarnobrzeg, and in October of the same year the deportation and transportation of Jews to the ghettos began. At that time, there were about 3,800 Jews living in the ghettos, which was almost 70% of the population. After the town was occupied, the Germans executed a number of Jews in the market square in Tarnobrzeg. They then created a ghetto around the former rabbinate and synagogue building, where about 100 people were detained.

Having occupied the town on September 17, 1939, the Germans executed five Jews in the market square. Starting on October 2, 1939, the Germans resettled part of the Jewish population in Mielec and Sandomierz, while others were taken across the river San into the Soviet-occupied zone. The German-Soviet demarcation could be crossed near Radomysl and Sieniawa. As the Jews were being transported to Radomysl, police from the post in Grabczyny ferried them to the other side of the San. Several times, halfway across the river, they ordered the Jews to jump out of the boat into the water. A few families who went back to the town were shot by the Germans in Baranów Sandomierski in 1942.

In early 1940, the Germans set up a labor camp for Jews in the former rabbinate and synagogue building, where they locked up about 100 people. Those who died of exhaustion were buried in the local Jewish cemetery. The camp was dissolved in mid-1942. After the war, the Jewish community in Tarnobrzeg never picked up again.

In Tarnobrzeg, there was a Jewish quarter called Dzików. There were two cemeteries there. One of them was closed at the end of the 19th century, most likely because there was no more free space. It was destroyed during the Second World War, after which a market was built on the site.

The second cemetery was also razed during the war and almost all the headstones were removed. There are now several headstones there including the ohel (grave) of the tzaddik (righteous/ wise man) Eliezer Horowitz and members of his family. The cemetery itself has since been listed as a historical site by the Provincial Conservator of Monuments.

Ohel in Tarnobrzeg (Source: Foundation for the preservation of Jewish heritage in Poland: website in English here)

There was also a synagogue in Tarnobrzeg, which is now used as a library. After it was destroyed during World War II, the building was renovated, and there is a plaque commemorating the Jewish community on one of the walls.

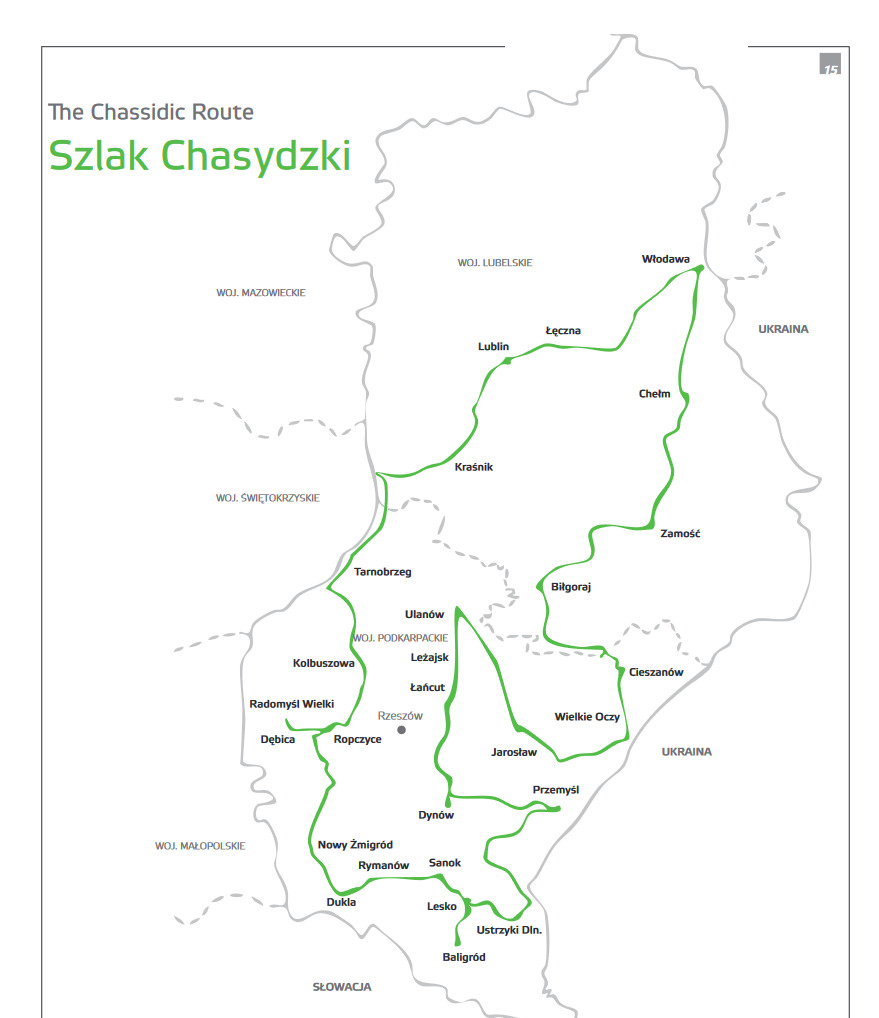

The Foundation for the Preservation of Jewish Heritage in Poland, backed by the Council of Europe, has recently opened the Hasidic Route, also known as the Chassidic Route, a tourist and historical itinerary that follows the footsteps of the Jewish communities in south-eastern Poland. The aim of this initiative is to stimulate the socio-economic development of the region by promoting its multicultural heritage to tourists.

Sigismond Bloch as a doctor during the First World War

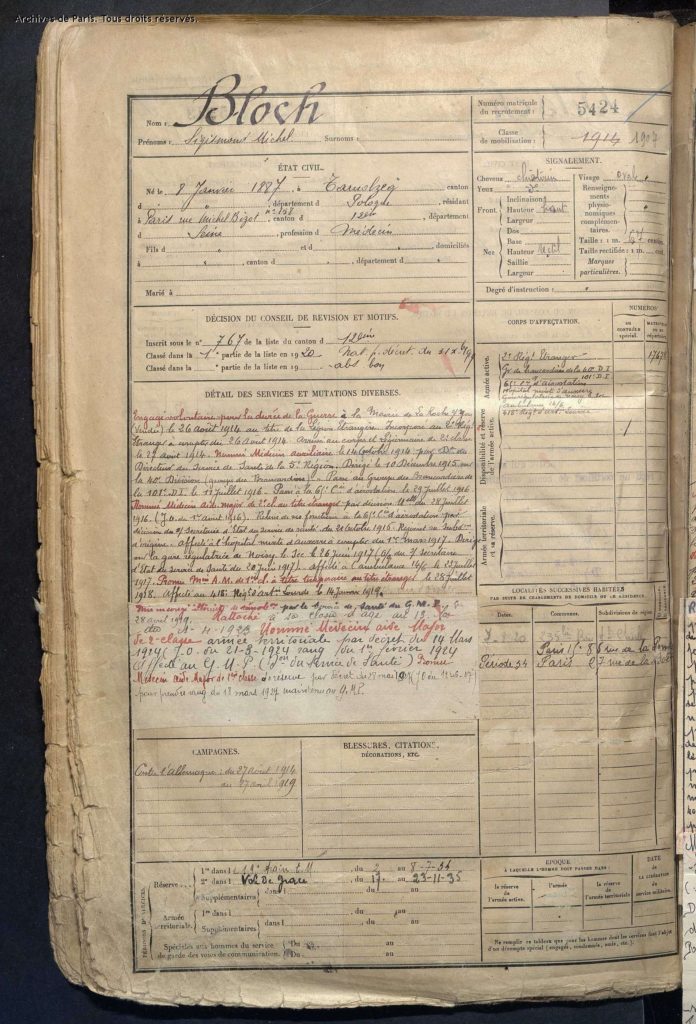

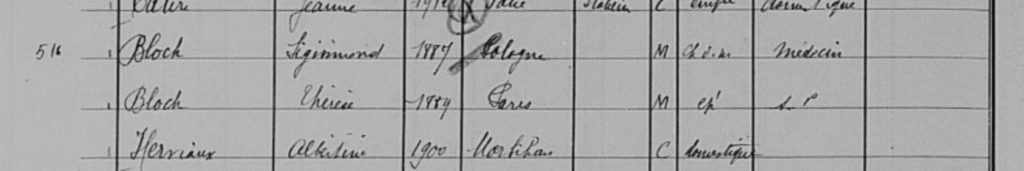

The French genealogy website, FILAE, says that Sigismond Bloch fought in the First World War. The following document can be found on the Paris Archives website, in the 1887-1921 recruitment registers:

This military service database, held at the Paris Archives, provides information on people involved in the wars.

Sigismond Michel Bloch, who was born in Poland in Tarnobrzeg and was then living on rue Michel Bizot in Paris, volunteered for the war at the age of 27 on 26 August 1914.

He was a doctor, appointed by the head of the health service of the 5th region, and became a doctor for the Foreign Legion behind the front line. He treated the “gueules cassées” or “broken faces”, meaning facially disfigured soldiers.

He was then transferred to La Roche sur Yon, where he was appointed as an auxiliary doctor on October 14, 1914. In 1917 he was sent to Auxerre, in central France, where he was assigned to the hospital, then to Noisy-le-Sec on the outskirts of Paris and finally to the 418th Heavy Artillery Regiment as a doctor assistant-major 1st class.

This document is a service record, known in French as a “feuillet matricule”.

A doctor under the Vichy regime

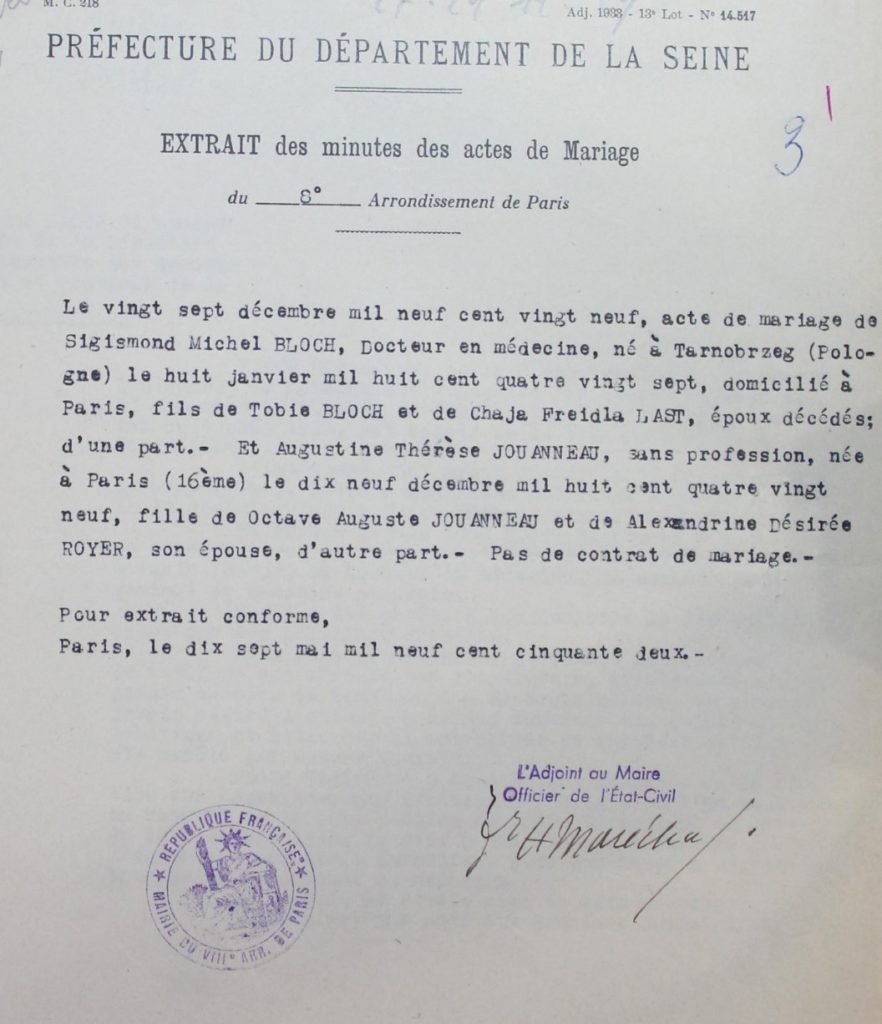

According to the 1936 census, he then lived in the 8th district of Paris together with his wife, Augustine Thérèse Jouanneau, who he had married in 1929 in the same district. His parents were Tobie Bloch, an industrialist and Chaja Last.

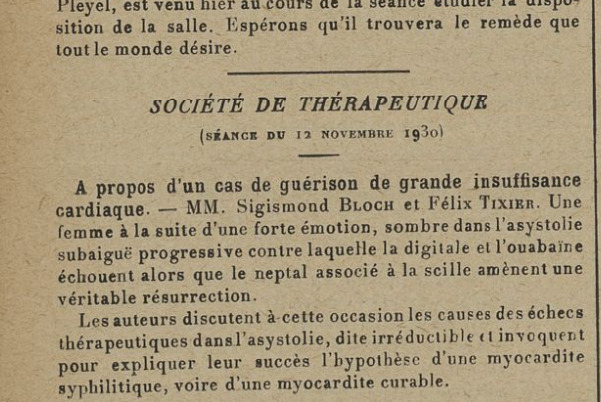

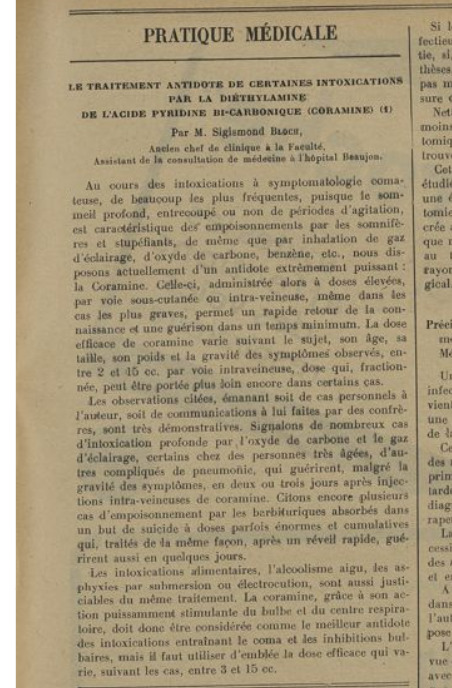

On the Universities of Medicine of Paris website, there are some articles written by Sigismond Bloch that were published in the French Hospital Gazette. He was a general practitioner and had his own medical practice:

There is another from March 1934, when he was a medical assistant at the Beaujon Hospital:

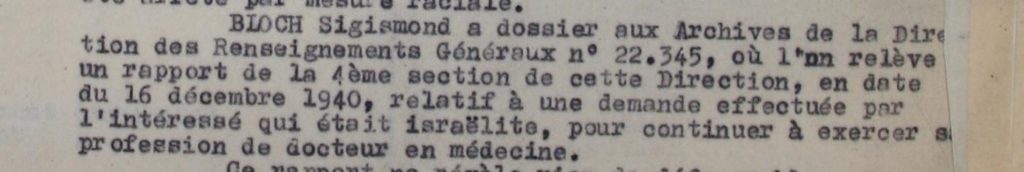

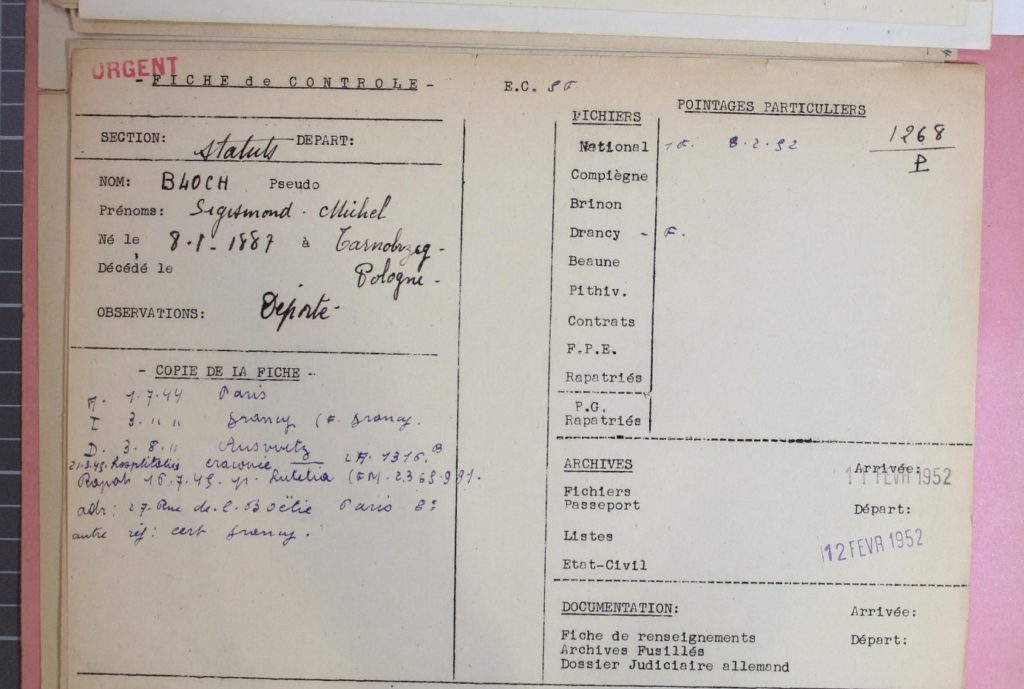

His deportation record mentions that he asked permission to continue to practice as a doctor:

Source: DAVCC (Victims of Contemporary Conflicts Archives Division of the Ministry of Defense Historical Service.)

According to the Vichy laws and the law dated August 16, 1940 in particular:

“No one may practice the profession of medicine in France unless he or she is a French national born of a French father”. Exemptions were made for those “who have scientifically honored their adopted country” and those who served in a combat unit during the wars of 1914 and 1939.

We suppose that Sigismond Bloch may have been granted an exemption due to the fact that he was a veteran who obtained the Volunteer Combatant Cross during World War I and had been naturalized as a French citizen for many years, but we have no proof of this.

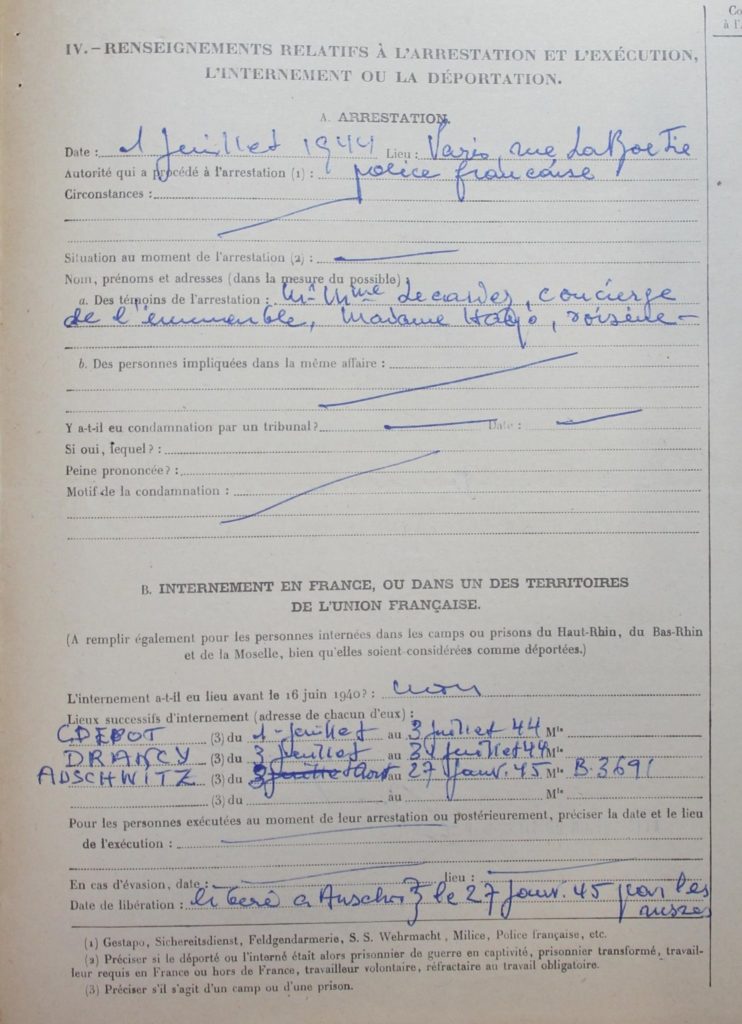

The circumstances in which Sigismond Bloch was arrested and deported

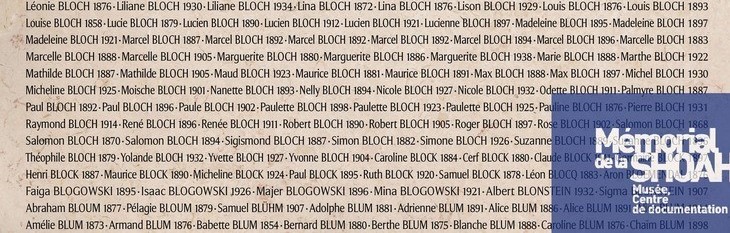

During their visit to the Shoah Memorial in Paris, the Parisian students were able to see Sigismond’s name on the Wall of Names.

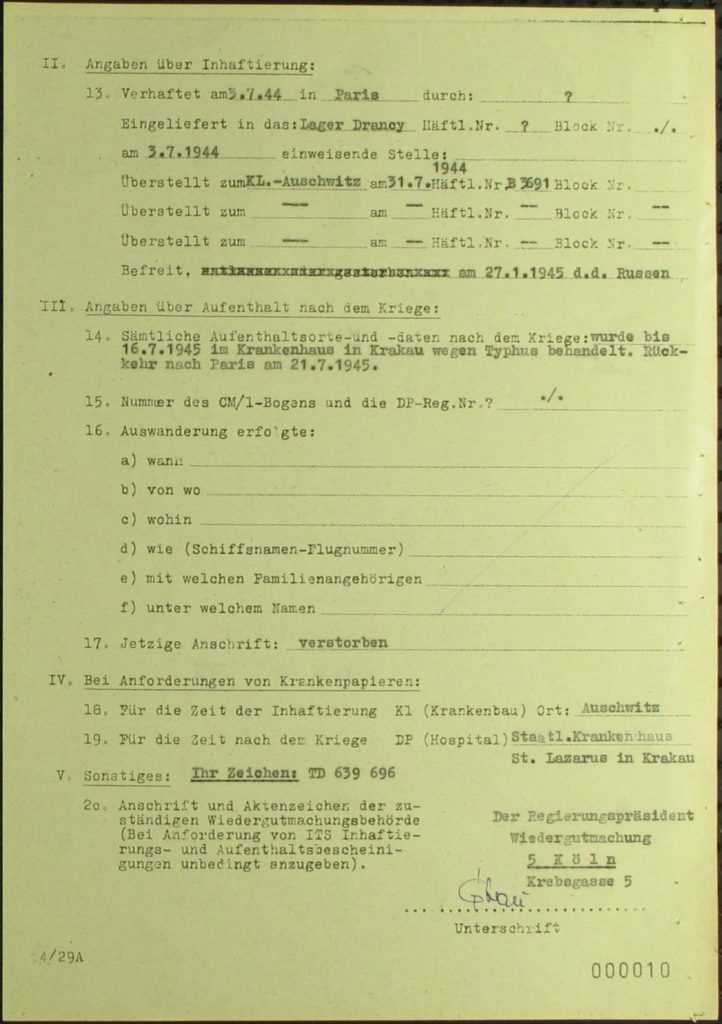

According to the application to have Sigismond Bloch recognized as having been a political deportee, the French police arrested him on July 1, 1944 at his home on rue de la Boétie in the 8th district of Paris. Also present were his wife, the concierge, Ms. Lecarier, and a neighbor, Ms. Hayo. It states that he was arrested on racial grounds and because he had issued medical certificates deemed to be “convenient”, not so as to avoid being drafted (he was 57 years old and no longer old enough to fight), but to avoid being deported. He was taken to Drancy camp on July 3, 1944 and deported to Auschwitz on July 31, 1944, where he remained until January 27, 1945. He was repatriated to the Lutétia Hotel in Paris in March or July 1945.

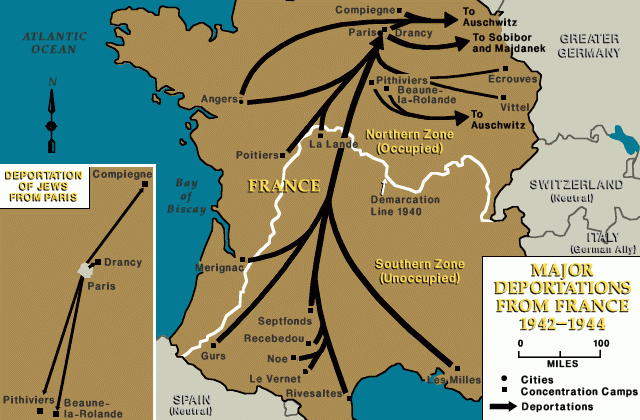

In 1944, France was divided in two. The free zone, in the south, was ruled by Marshal Pétain, who had been in power since 1940, and the occupied zone in the north, which had been taken over by Nazi Germany, also in 1940.

Source: United States Holocaust Memorial Museum

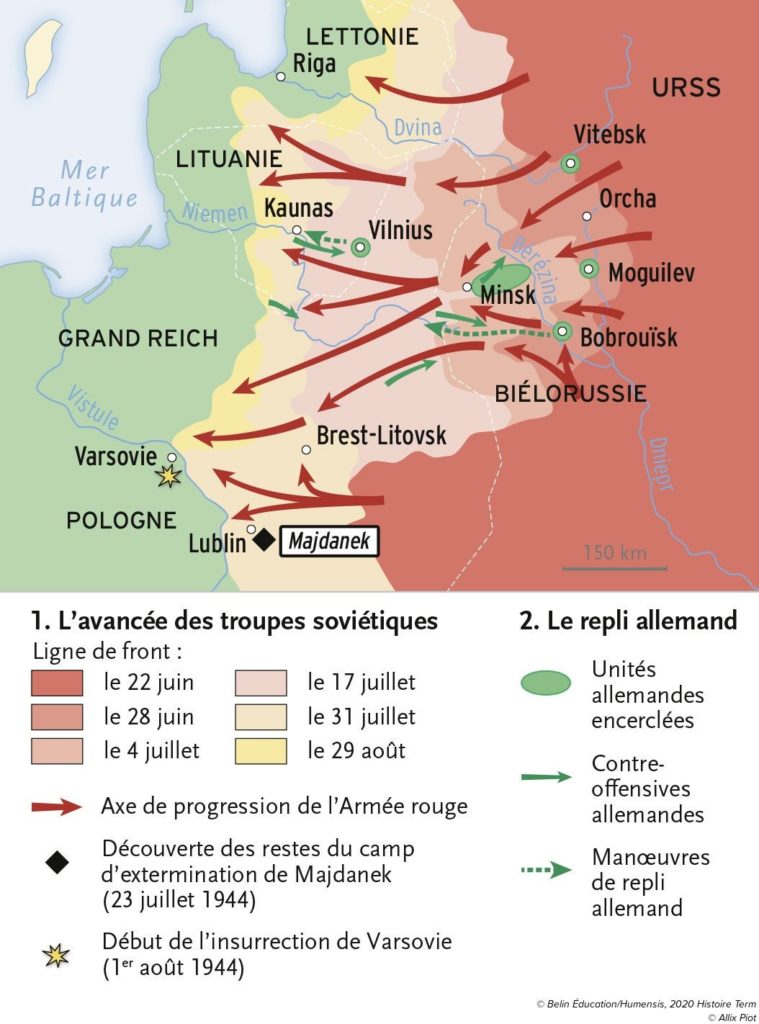

The Russian army’s victories over the German army in Europe (including Stalingrad on February 2, 1943) enabled it to conquer and/or recapture a number of areas, particularly on the Eastern front, including in Finland, Romania and Bulgaria, where the Germans retreated. Moreover, on the Western Front, the conquest of Italy (one of the three Axis countries, together with Japan and Germany) began in January 1944.

The Eastern Front: In the summer of 1944, the Russians launched a major offensive, which liberated the remainder of Belarus and Ukraine, the Baltic states, and eastern Poland from Nazi domination. In August 1944, the Soviet troops crossed the German border.

Nazi Germany began to lose more and more battles to the USSR and on June 6, 1944, the Americans, British, Canadians and some French resistance fighters led by General de Gaulle landed in Normandy. Faced with successive military defeats, Hitler ordered the German troops to deport and kill more Jews.

This was the context in which Convoy 77, one of the last large convoys from France, was organized. It left Drancy for Auschwitz on July 31, 1944, carrying more than a thousand Jews.

The German troops in France became even more focused on their task, aware that there were only a short time left before the Allies reached Paris. This proved to be true, since Paris was liberated on August 26, 1944.

Sigismond Bloch was arrested and deported about a month after the Allied landings in Normandy and a month before Paris was liberated. This marked the end of the Vichy regime (which was replaced by the CFLN, the French Committee for National Liberation, which became the new government) and the last council of ministers in Vichy was held on July 12, 1944. For the German army, it was a debacle. France was liberated little by little thanks to the Allies.

Internment in Drancy camp

The class visited the Drancy Memorial in March.

During their visit to Drancy, the students were able to listen to some testimonies of children who were interned in Drancy camp, such as Francine Christophe, Jacques Szwarcenberg, Annette Landauer and Gil Tchernia.

Francine Christophe was arrested together with her mother in 1942, when she was eight and a half years old. They were deported to the Bergen-Belsen concentration camp on May 7, 1944 on Convoy n°80. Jacques Szwarcenberg was deported to Bergen-Belsen in February 1944 at the age of 11. Annette Landauer was arrested during the Vel d’Hiv roundup in 1942 and imprisoned in Drancy when she was 11 years old. Gil Tchernia was arrested and imprisoned in Drancy in 1943, when he was 4 years old.

When they arrived in Drancy, the German authorities, their agents or the French police searched through their luggage, if they had any. They were then registered and those who did not already have a yellow star were made to wear one.

Communication with the outside world was allowed. People from the outside sent food packages to the deportees, which they shared among themselves in their rooms. They sent letters sewn into the hems of clothes, which were hardly visible, so that the German authorities would not notice them.

The witnesses describe the rooms as smelly, with blood-stained, disgusting mattresses on the floor. The internees were divided into 60 rooms, so there was no privacy. There were no showers, so they had to wash themselves with water from a faucet.

The testimonies of those who survived prove that they were the exception to the rule, as the vast majority of the internees were deported and died in the killing centers. It can be said that they were “lucky” to escape death, but nevertheless they lived in atrocious conditions. They were afraid, hungry, filthy, disease ridden and often subjected to violence. These witnesses now remember Drancy camp as a place where they suffered enormously. It is an experience that they never want to forget, a part of their personality and their moral values are influenced by the time they spent in Drancy. Seeing it again helps them to rebuild their lives, and although they would have preferred it to become a museum, some of them believe that the fact that the Drancy camp has been converted into a low-cost housing project also symbolizes renewal and renaissance.

Students’ impressions

“One story particularly struck me: the one in which one of the former internees recalled that when he was playing on a balcony with some other children, a German soldier shouted loudly and pointed his gun at them. This episode attests to the brutality of life in the camp and the cruelty of the guards.”

“The children were treated the same as the adults. The majority of the guards had no mercy toward them and even went as far as hitting them.”

“Another thing that made an impression on me were the drawings made by the internees: dark, sad and gloomy, they depict life in the camp. This bleak and dismal way of depicting what they saw shows their despair at being interned in the camp, as shown by the titles of these drawings, “Living like a dog” and “On the threshold of hell” in particular.”

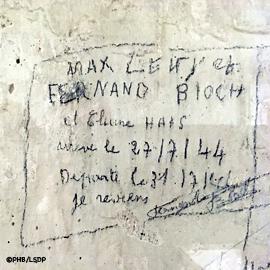

“I also saw the remains of a wall on which is engraved a name, the date of arrival and deportation and a phrase that moved me immensely, which is “I will be back”.”

Fernand Bloch, Max Lévy and Eliane Haas were deported on Convoy 77

“What moved me the most was the story of the tunnel built by the internees to escape and then discovered by the guards. Luckily, the 12 internees who were caught were sent to another camp. On the train, they managed to escape along with the other people in the car.”

2. https://www.fondationshoah.org/memoire/les-evades-de-drancy-de-nicolas-levy-beff

“The hunger and the incessant noise seemed to come up again and again in the testimonies; it must have been really traumatic for them. The sanitary conditions were appalling and I can’t understand how people enjoyed making other people suffer like that. One thing that came up a lot in the testimonies, even though the camp survivors who were interviewed were not asked about it, was the fact that they did not want to be noticed because of the risk of being hurt. The example given of how important it was to respect this unwritten rule is quite simply horrifying and chilling: turning a gun on children because they were playing noisily is appalling.”

“One thing that really amazed me was that people (police officers and their families) voluntarily agreed to live in the towers overlooking the camp and thus were able to watch men, women and children suffering all day long. These people were despicable.”

“What impressed me the most during our visit to Drancy was the railroad car. This SNCF wagon was used to deport Jews to Auschwitz to be slaughtered like cattle.”

“What struck me during the visit to the Drancy Memorial and listening to the testimonies was the lack of hygiene. Knowing that people slept on the floor on mats full of excrement and that they could not wash themselves at the taps with even a little privacy shocked me. Also what struck me during this visit and listening to testimonies was the how hungry these people were in the camps. Parents would sacrifice themselves so that their children could eat and not go hungry by giving them their own food. The little boys rummaging through the garbage looking for leftovers and eating whatever they could really made my heart ache. No one deserves to be that hungry and everyone should have enough to eat. Life in the camps was monstrous for everyone and I think even more so for those who were there without their parents.”

“The fact of seeing the enormous number of children who were interned really struck me; it seemed unthinkable and senseless to me to see so many children living in such conditions, most of them without their mothers and for reasons that were completely incomprehensible at their age. No one deserves to live in such poor living and sanitary conditions no matter who they are, regardless of their background, religion or sexual orientation. These children deserved nothing of what they went through.”

“During the visit to the Drancy Memorial, the thing that struck me most was the children who must have been left with no points of reference, no parents and no brothers and sisters. And when, during their testimony, one of them said that because their soup was not enough for them, they waited for the cooks to take out the garbage so that they could eat whatever they could find. Because they were very hungry, and that made me react immediately because I find it sad that a child could not eat as much as he or she wanted.”

The testimony of a person deported to Birkenau: Ginette Kolinka

Sigismond Bloch was deported in July and Ginette Kolinka in April. Both of them returned to France.

The page dedicated to Ginette Kolinka on the Shoah Memorial website:

3. https://ressources.memorialdelashoah.org/notice.php?q=fulltext%3A%28cherkasky%29%20AND%20id_pers%3A%28%2A%29&spec_expand=1&start=2

In April, Ginette Kolinka, née Cherkasky, who was deported on Convoy n°71, met with the students at their school in Paris. Here are some of the students’ observations:

“Ginette Kolinka told us what she had experienced at the age of 19 when she was taken to Drancy, together with her father, brother and nephew on March 13, 1944 by the Gestapo, after they were turned in. She was later deported to Birkenau with her family on Convoy 71, as was Simone Veil. During her story, we all felt many different emotions. For my part, I felt sadness mixed with empathy, and hatred but also joy. The main thing I felt was hatred towards the Nazis. This hatred came over me when she told us about when she arrived at the camp; the women were separated from the men and taken to a separate place. Other women ordered them to undress in front of everyone, and shaved their entire bodies including their heads. Then a number was tattooed on their forearms. The fact that they shaved the women’s heads and tattooed them like animals made me realize that the Nazis were totally dehumanizing the Jews.

Sadness and empathy also came over me when she told us in detail about getting off the train. There were trucks filling up with people who were very young or too tired to continue the journey to the camp on foot. Ginette Kolinka suggested to her father and brother that it would be easier if they got into a truck because they were so tired from the journey. It was only a short while later that she heard that these trucks were going straight to the gas chambers. Those who were able to work were sent into the camp. Getting off the train was the last time she saw the rest her family.”

The return to France

On January 27, 1945, Soviet troops arrived in Auschwitz, Birkenau and Monowitz. There they found more than 6,000 prisoners, most of whom were sick and dying.

Sigismond Bloch stayed at the St. Lazare hospital in Krakow from January to July 1945, where he was treated for typhoid fever until he was repatriated to the Lutétia Hotel in Paris.

Source: DAVCC (Victims of Contemporary Conflicts Archives Division of the Ministry of Defense Historical Service)

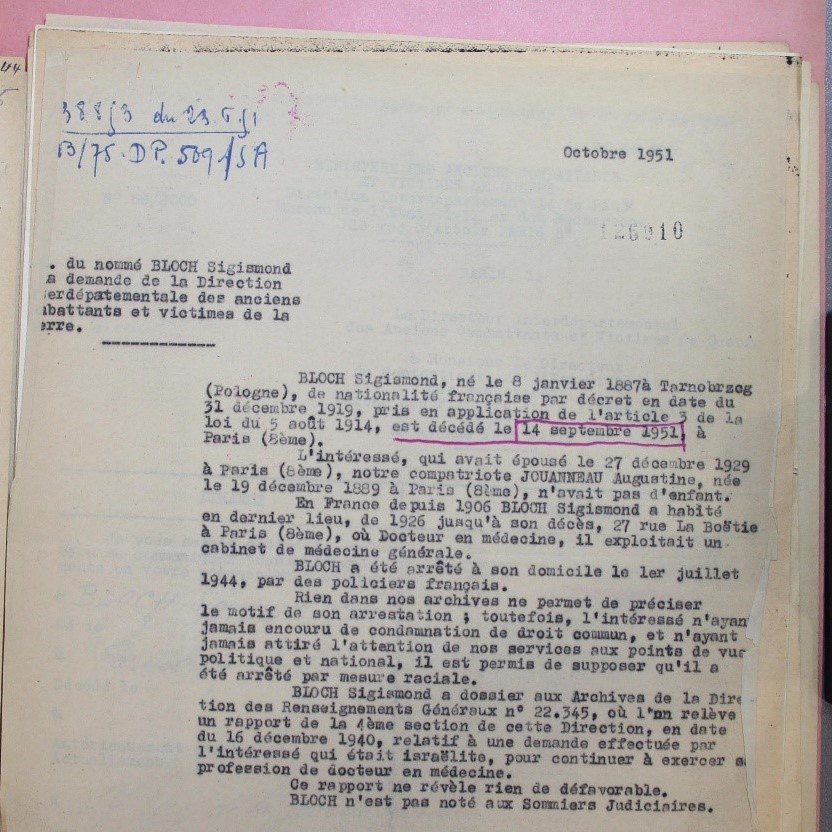

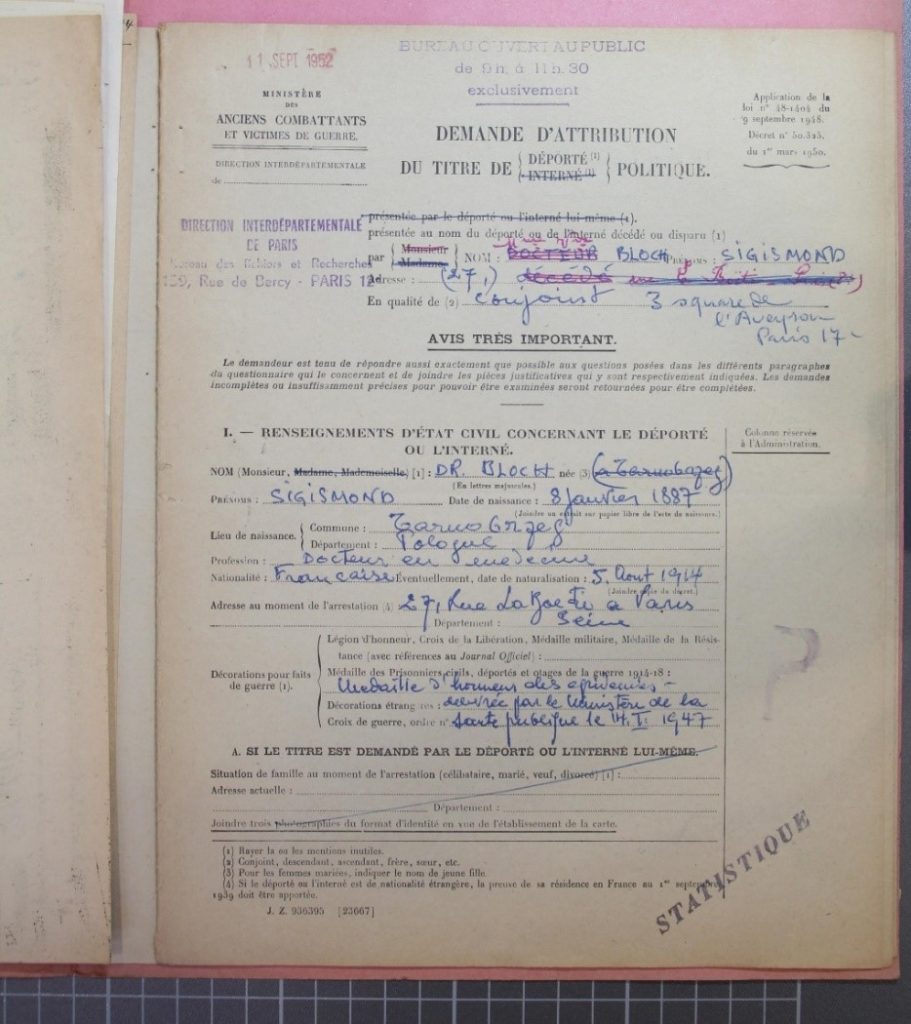

He died at his home on rue de la Boétie in the 8th district of Paris on September 14, 1951. He was 64 years old, and it was six years after he returned from the camps. After the war, his wife began to carry out research and to have his status recognized. She was then living in the Square de l’Aveyron in the 17th district of Paris.

Source: DAVCC (Victims of Contemporary Conflicts Archives Division of the Ministry of Defense Historical Service)

Sources:

– Gutwein Y., Mémoires de mon shtetl, Dzikow (Tarnobrzeg), Paris 1948.

– Baran A. F., Tarnobrzeg – Shalom, « Tarnobrzeskie Zeszyty Historyczne » 1991, n° 1.

– Reczek K., Les Juifs dans ma mémoire, « Tarnobrzeskie Zeszyty Historyczne » 1991, n° 1

– Piotr Wróbel, « Żydzi polscy w czasie I wojny światowej », 1992.

– Encyclopedia United State Holocaust Memorial Museum.

– Paris Archives.

– Medical Archives (Médica Digital Library Archives).

– Archvies held by the DAVCC (Victims of Contemporary Conflicts Archives Division of the Ministry of Defense Historical Service)

– The Arolsen Archives.

Français

Français Polski

Polski