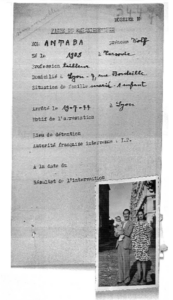

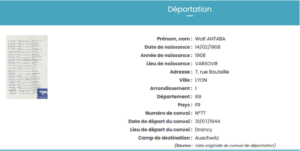

Wolf ANTABA

Wolf Antaba was born in Warsaw, Poland, on February 14, 1908. HIs parents were Naphtali Antaba and Sara Perelstein.

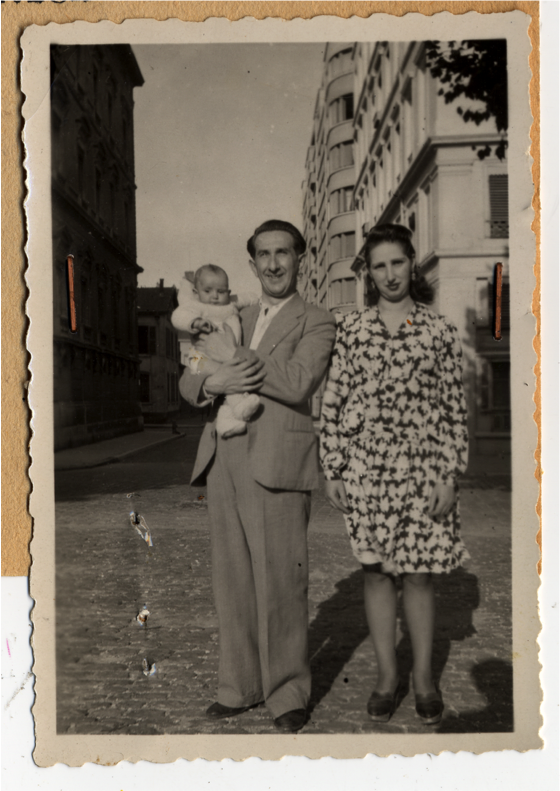

Wolf Antaba’s marriage certificate

Source: Paris archives

When Wolf was born, present-day Poland was divided into three sections: the first, which included Warsaw, was under Russian rule, another was under Austrian rule and the last was under German rule.

At the beginning of the 20th century, there were some 350,000 Jews living in Warsaw, which was roughly 30% of the population. It was the largest Jewish community in Europe, and the second largest in the world after New York. The Jews lived mainly in the north of the city, in Muranów and on the right bank of the Vistula river. Most of them were traders and craftsmen. There were 142 synagogues, as well as numerous prayer houses.

Wolf left Poland when he was 20 years old. By that time, the country had been unified into a single state since 1918, and in 1921 the new constitution had granted the Jewish population equal rights and freedom of worship. Many people, including Wolf, decided to leave their homeland nevertheless, some to escape poverty, others in response to anti-Semitism.

In 1928, Wolf moved to France, and found work as a tailor for the Rottermann company at 32 rue de Bondy in the 10th district of Paris.

.

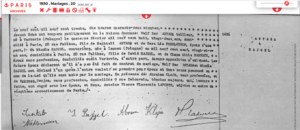

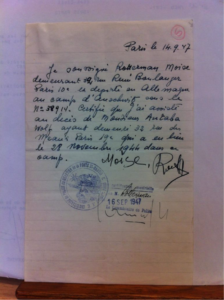

Wolf Antaba’s request for release from Bou-Arfa, April 1941

Source: French foreign legion archives

Two years later, on August 9, 1930, he married Mindla Bajgel. The couple went on to have one child together. We do not know its sex or date of birth but various records mention a child.

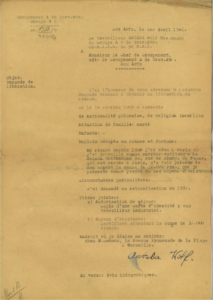

Montluc prison information sheet, dated July 19, 1944

Source: Montluc files

According to the records, the family lived at a number of different addresses, mainly in the 19th and 20th districts of Paris, which were home to a large number of Jews from Central and Eastern Europe. In fact, in 1939, there were some 130,000 Eastern European Jews living in Paris. They were not a homogenous group, however: there was significant disagreement between traditional religious groups and those who believed in socialism. The Jews tended to work in relatively insecure jobs, such as street vendors, fairground workers, second-hand goods dealers, tailors, dressmakers, knitters and cobblers.

In 1937, Wolf applied to be naturalized as a French citizen, but his request was turned down. A year later, on April 5, 1938, he was issued with an identity card for “industrial workers”, valid for 3 years.

On September 1, 1939, Germany invaded Poland. As a result, two days later, on September 3, France and Great Britain declared war on Germany. A large number of foreign Jews signed up to join either the foreign volunteer marching regiments, the French section of the Polish army , the Czechoslovakian army or the French Foreign Legion. Wolf Antaba, who was 31 years old by that time, enlisted in the Foreign Legion on October 4, 1939. He signed up at the Seine Central recruitment office for the entire duration of the war.

Enlistment agreement for the Foreign Legion, 1939,

Source: French Foreign Legion archives (page 8)

On November 15, 1939, he arrived at the Sidi-Bel-Abbès camp in Algeria, where he was to be trained. He was appointed 2nd class legionnaire with the “compagnie de passage n°2”, which in legion jargon signified that it was a temporary position. Ten days later, on November 25, he was appointed to the “compagnie de passage n°3” in Bossuet, which meant that he was a regular soldier at last. Next, on January 17, 1940, Wolf was transferred to the “compagnie de passage n°1”. Two days later, on January 19, he was posted to Oujda, also in Algeria, where he was assigned to the 3rd Regiment on the 3rd Battalion of the 10th Company.

Information sheet, 1939-1940

Source: French Foreign Legion archives

After that, Wolf was sent to Morocco. He arrived in the Bou-Arfa camp, a provisions depot, on June 10, 1940.

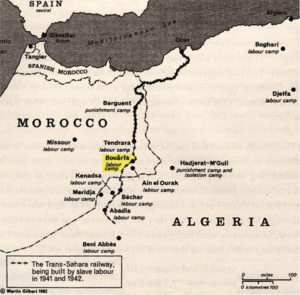

Map of forced labor camps in the Sahara, 1941-1942

Source: www.combattantvolontairejuif.org

There were many Spanish Republicans, French Communists and Jewish deportees from Central Europe in this camp. In fact, it was a labor camp for the construction and maintenance of railroads from the Mediterranean to the Niger.

Photo of men carrying out forced labor in the Bou-Arfa camp, taken by Sinforiano Rodriguez, a Spanish laborer and the Bou-Arfa survivor

The work was hard, and the pace at which prisoners had to work was both cruel and inhumane. The living conditions were equally appalling: many men died as a result not only of abuse, torture, sickness, hunger and thirst, but also from snake and scorpion bites. On September 14, 1940, Wolf was officially demobilized but kept on in the camp in foreign labor group B.

Wolf Antaba’s demobilization notice, September 1940,

Source: French foreign legion archives (page 3)

On April 1, 1941, Wolf requested his release in order to return to France. He had to provide proof of income, an address in France and that he held an “industrial worker” identity card. His application was successful, and on May 1 he was sent back to Marseille, on the south coast of France.

We have no information as to when or why Wolf decided to move to Lyon, in the Rhone department of France but it was there, in 1944, that he was arrested at 7 rue Bouteille, in the Saint-Vincent district of the city. Might he have been living nearby, or was he just passing through?

He was probably taken to the Gestapo headquarters on Place Bellecour. The Gestapo had moved there a few months earlier after an Allied bombing raid on the Lyon-la-Mouche railway destroyed its former premises on avenue Berthelot.

In the summer of 1944, after the Allies landed in Normandy on June 6, 1944, the Germans began to retreat. This did not stop them from continuing to arrest as many Jews as possible, however. They also began to take a harder line with the population in general, by carrying out more frequent identity checks and searches of people’s homes. Wolf Antaba, who until then had managed to evade the Nazis’ clutches, was arrested just a few weeks before Lyon was liberated on September 3, 1944.

According to the Montluc prison records, Wolf Antaba was arrested on July 19, 1944 by a French police officer, although other records say that it was the Gestapo. Either way, he was arrested on grounds of his “race” and was then searched and had his belongings confiscated. He was then taken to Montluc prison, at 4 rue Jeanne Hachette in the 3rd district of Lyon. The Germans took over Montluc on January 7, 1943, and from then on it played a key role in Nazi repression.

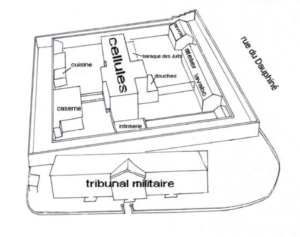

Plan of Montluc prison

Source: museedelaresistanceenligne.org

We do not know if Wolf was held in one of the prison’s 122 cells, in which living conditions were exceptionally difficult: the cells were only about 43 square feet in size, and up to 8 people were held in them. The lavatories were just tin buckets and the prisoners slept on straw mattresses on the floor.

He may have been held elsewhere in the prison. The Nazi authorities gradually converted shower rooms, dining halls, washrooms and workshops into holding areas.

Lastly, he may have been held in the “Jewish barracks”, a separate hut in the yard used to hold member of the Resistance and Jews over 15 years old.

The Jewish barracks in the main courtyard in Montluc

Source: Rhône departmental archivers, ref. 4544 W 17

There is nothing left of the hut now other than a gravel outline in the courtyard, but it was built of wood and canvas and, in the summer, was used to hold up to 100 prisoners.

Wolf spent a week in prison in Lyon and was then sent to Drancy, where he arrived on July 26, 1944.

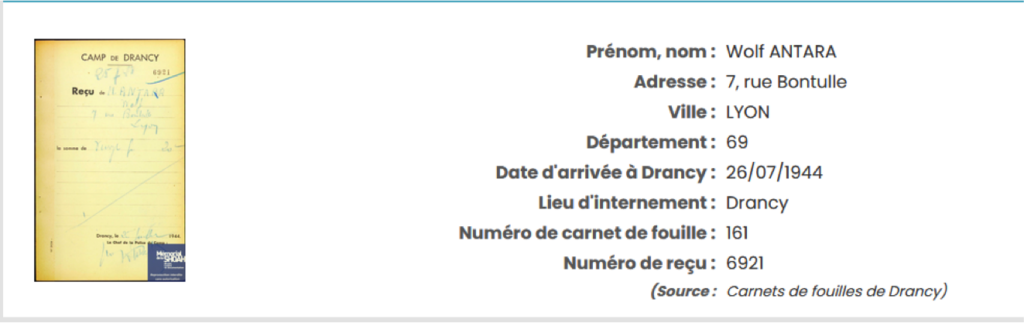

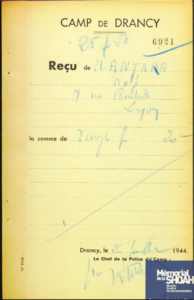

Receipt in the name of Wolf Antaba, dated July 26, 1944, from the Drancy search record book

Source: Shoah Memorial, Paris

Drancy camp was a group of buildings, comprising two tower blocks and five low-rise blocks, originally built between 1931 and 1937. Known as the “Cité de la Muette”, it was originally intended to provide low-cost housing for local families. In 1942, the Nazis took it over and used it as a transit camp for Jews, as it was close to two train stations, Le Bourget and Bobigny.

The “horseshoe” shaped group of buildings thus became an internment camp. The four-storey U shaped buildings were built around a central courtyard, some 200 yards long and 40 yards wide. The taller towers in the corners were used as watchtowers. It was surrounded by a sentry path and a barbed wire fence.

When Wolf arrived in Drancy, he was booked in and searched. His receipt number was 6921, from log book 161. We know from many first-hand accounts that living conditions in Drancy were very tough. Sanitary facilities were poor, there was not enough food and some internees contracted dysentery. The guards humiliated the prisoners and punished them repeatedly. Wolf spent a week in Drancy before being deported to Auschwitz on July 31, 1944.

List of people deported from Drancy on July 31, 1944

Source: Shoah Memorial, Paris

When the SS herded the Jews onto the train, Wolf did not know where they were going, but he probably guessed what was about to happen to him. He may have listened to Radio London, which reported on what was happening to the Jews in the camps and Eastern Europe.

The deportees were crammed together in cattle cars, where there was only a tin bucket for them to relieve themselves, and according to other deportees’ testimonies, the smell soon became unbearable. The journey lasted 3 days and 2 nights, with no food or water. What must Wolf have felt on the journey? Despair? Resignation? Did he think about his beloved Mindla, and their child?

The train arrived in Auschwitz on the night of August 3, 1944, and the deportees climbed down onto the ramp. They had no idea what to expect. The selection took place immediately. They were split into two lines: men on the right and women and children on the left, and then according to their age, physical condition and health. Either they were taken straight away to the gas chambers and executed, or, if the doctors thought they were fit enough they sent into the camp for forced labor. Those who went into the camp were registered, had to take a shower and were then given some clothes. Of the 1,310 people who were deported on Convoy 77, 836 were sent to the gas chambers as soon as they arrived. Wolf, however, was not among them. At the age of 36 and at his prime, he was selected for work.

We do not know exactly what happened to Wolf Antaba over the next four months. We assume that, together with the other men from his convoy, some of whom survived and later testified, he was kept in Auschwitz, placed in quarantine, and then forced to work in a stone quarry outside the camp.

The weather in the early winter of 1944 was terrible. It was exceptionally cold, and the prisoners had too few clothes to endure such conditions. Wolf died on November 28, 1944, although the exact reason for his death is not known. Was he killed by an overly-aggressive guard? Did he fall victim to exhaustion or disease? Or was he sent to the gas chambers and murdered after one of the regular selections that the prisoners had to endure?

Wolf became yet another of the 1059 victims of Convoy 77, and another of the 6 million others who died simply because they were born Jewish.

Wolf’s wife survived, but there is no mention of a child in the various official forms she filled in after the war. Was he too a victim of the Nazi savagery, or did he simply die of an illness or as a result of an accident?

Wolf Antaba’s family shared the same tragic experience as thousands of Jewish families during the Second World War.

Confirmation of the death of Wolf Antaba

Source: Victims of Contemporary Conflicts Archives Division of the Ministry of Defense Historical Service, in Caen.

Videos produced by the 9th grade students at the Haute Azergues secondary school

Explanation

From Warsaw to Auschwitz, following in the footsteps of Wolf Antaba, who was deported on Convoy 77

Français

Français Polski

Polski