Wolf FAKTOR

My name is Wolf Faktor. I was born on August 6, 1901 in Pustelnik, Poland. This is my life story, as told by the 12th grade students of class TG3 at the François Villon high school in Paris, France.

The student also produced a podcast, in French, which was awarded the CNRD (the French National Resistance and Deportation Competition) “Prix du Souvenir français” at the Paris academy in 2024: Le parcours atypique de WOLF FAKTOR raconté par les élèves de TG3

Wolf’s family in Poland

Wolf Faktor’s life was shaped by war and deportation. He married his first wife, Macha Euker, in Poland and the couple had four children, who were aged 1, 3, 5 and 18 in 1930. When Wolf left the country in the 1930s, the children stayed behind in Poland with their mother.

His first experience of war

Poland became an independent country in 1918. Between 1919 and 1921, the Soviet Union went to war with Poland in an attempt to gain territory. The two countries fought over the border regions. Wolf fought on the side of the Polish army, but was taken prisoner by the Russians in 1920. He was subsequently awarded the Polish Resistance Medal, which testifies to his courage and bravery.

We suppose that Wolf Faktor returned to Poland between 1930 and 1939, but there is no accurate information in the records about this. As for his life in Poland, we have almost no information at all, as the records are all in Polish. All we know is that he re-enlisted in the Polish army in France in 1939, after the Germans invaded the country.

From Poland to France

Wolf Faktor emigrated to France in the 1930s. His native Poland had been the scene of a series of pogroms, in particular between 1917 and 1921. When he arrived in France, he set up home at 9 rue du Dr Paul Brousse in the 17th district of Paris, where he ran a second hand goods and hardware business. We also discovered that by that time, he was married to a Polish woman called Domicela Swolinska.

Wolf Faktor left his homeland amid a hught wave of Jewish migration. During the Nazi occupation, the native Polish population became eager to report their Jewish neighbors. The Nazis succeeded in stirring up and then exploiting anti-Jewish sentiment in all the countries they occupied.

From patriotism at home to loyalty to his adopted country

Wolf Faktor enlisted in the French section of the Polish army on September 4, 1939. He joined the 1st artillery regiment, which was stationed in Coëtquidan, in the Brittany region of France. A Paris Police Headquarters report states that he left his home in Paris the previous day, and enlisted as a volunteer. A Franco-Polish agreement had been signed in May 1939 with a view to founding a Polish infantry division within the French army which would recruit Polish nationals who had migrated to France. Wolf Faktor signed up as soon as the new army camp was up and running, well before Polish citizens in France were mobilized by law on October 3, 1939. The Polish army thus fought on French soil as allies. By June 18, 1939, there were 85,000 Polish soldiers in France. Some of them went to serve in England, some, including Wolf Faktor, were taken prisoner, and some went into hiding and joined the Resistance.

And so it was that Wolf Faktor fought for France. However, on May 23, 1940 he was wounded in the Marne department, then on July 5 he was taken prisoner and interned in Frontstalag 133, a German prisoner-of-war camp in Rennes, in Brittany. This was one of a number of transit camps used to hold prisoners pending their transfer to Germany. He was subsequently transferred to two other Frontstalags, the first in Quimper, in Brittany, and the second in Péronne, in the Somme department.

An “expert escape artist”

On October 26, 1940, Wolf Faktor escaped, together with a man called Georges Duchêne, but was soon recaptured. He then escaped for a second time, but on September 2, 1941 the Gestapo caught up with him and tortured him in an attempt to get him to reveal the names of his colleagues. He refused to talk. On September 23, 1941, he was transferred to the Cherche Midi prison in Paris. He stayed there until January 22, 1942, when he was transferred to Saint-Quentin prison in the Somme department. He escaped from there on April 28, 1942 but once again, he was recaptured. This time, he was taken to Germany, first to Stalag V-A. in Ludwigsburg on November 14, 1942, and then to Stalag V-B in Willingen on April 27, 1943.

Marie Moutier-Bitan, a historian, told us the difference between a Frontstalag and a Stalag. Both were prisoner of war camps run by the Wehrmacht, the German army. Frontstalags were transit camps near the front. Soldiers who were captured as prisoners of war were then transferred to permanent Stalags. This explains why Wolf Faktor was moved from one camp to another. Marie Moutier-Bitan also told us that the chances of survival for the soldiers from Eastern Europe were slim, at around 10%, whereas for soldiers from Western Europe, the figure was 90%.

On July 20 1943, Wolf Factor was repatriated to France on health grounds. A medical certificate states that he was suffering from tuberculosis. He was admitted to the Charasse hospital in Courbevoie, north west of Paris.

The fact that he enlisted in the army voluntarily illustrates his determination to oppose the Nazis in both his native and adopted countries. He managed to survive, and escaped several times. This demonstrates both his ability to evade the German authorities and his unfailing resolve.

His work in the Resistance

Wolf Faktor joined the ranks of the CLDR (Ceux de la Résistance, or Those of the Resistance) movement in July 1943, and worked with the group until he was arrested on July 28, 1944. The CLDR specialized in propaganda, intelligence and various other activities, such as stockpiling and supplying weapons to Resistance fighters. It was also involved in rescuing Allied pilots, who, when they came down in hostile territory, needed help to survive and make their way to England.

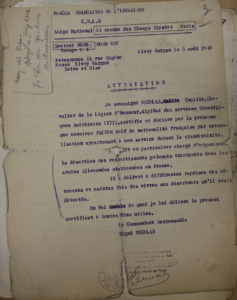

In a letter dated August 3, 1945, Camille Nicolas confirmed that Wolf Faktor was a member of the Resistance. This testimony proved essential for Wolf, as in 1941, Camille Nicolas had founded the M4 network, which comprised a number of different groups, including Ceux de la Résistance. An important figure in the French Resistance movement, he detailed Wolf Faktor’s role and supported his application for the status of deported resistance fighter.

Camille Nicolas’s letter confirming Wolf Faktor’s role in the Resistance

Wolf Faktor was responsible for arranging for Polish nationals who had been drafted into the German army in France to desert and for recruiting them into the resistance movement. These soldiers, who had been compulsorily drafted into the Wehrmacht, also stole weapons, including automatic rifles, which played a crucial part in the work of the armed Resistance groups. Wolf also set up an arms depot at 104 boulevard Bessière in Paris. Ernest Casimir, a French military police officer from Clichy, confirmed this.

A police officer from the Chapelle district, Michel Solaz, also described Wolf Faktor as a good patriot, and stated that he had come across him with some Polish soldiers carrying automatic rifles. Wolf Faktor was taking them to meet an F.F.I. (Forces françaises de l’Intérieur, or French Interior Forces) leader in Livry-Gargan, where several F.F.I. groups belonging to the M4 network were based.

From betrayal to deportation

A man by the name of Marcel Bonnet turned in Wolf Faktor, and the Gestapo arrested him as a result. Pierre Cazaux, his neighbor, confirmed that he had been living in hiding in two small rented rooms at 152 rue de La Chapelle. This time, he was interned in Drancy, which since 1942 had been a transit camp for Jews who were to be deported to concentration camps and Nazi killing centers, Auschwitz-Birkenau in particular.

Around 63,000 people passed through the Drancy camp before they were deported. Living conditions in the camp were abominable. Many internees slept on the floor, and there was not enough food to go around. Sanitary facilities were deplorable too, with prisoners only allowed to shower once every ten days.

Bobigny station, which was more discreet than the previously-used one in Bourget-Drancy, became the main departure point for deportation convoys from France. From July 18, 1943 to August 17, 1944, a total of 21 transports took place: in those 13 months alone, 22,453 men, women and children were deported. Bobigny station was in a more remote spot, so less visible to the local French population, who might have felt sorry for the deportees. Aloïs Brunner, the commandant of Drancy camp, chose Bobigny for tactical reasons. It enabled the Nazis, in collaboration with the SNCF, the French National Railway Company, to carry out the Final Solution more easily. Their aim was to wipe out the entire Jewish population in Europe.

Convoy 77 was the last of the large deportation transports of Jews from Drancy internment camp, via Bobigny station, to Auschwitz. Wolf Faktor almost certainly climbed onto the train amid much fear and screaming, as there were a large number of children on board. The train set off on July 31, 1944.

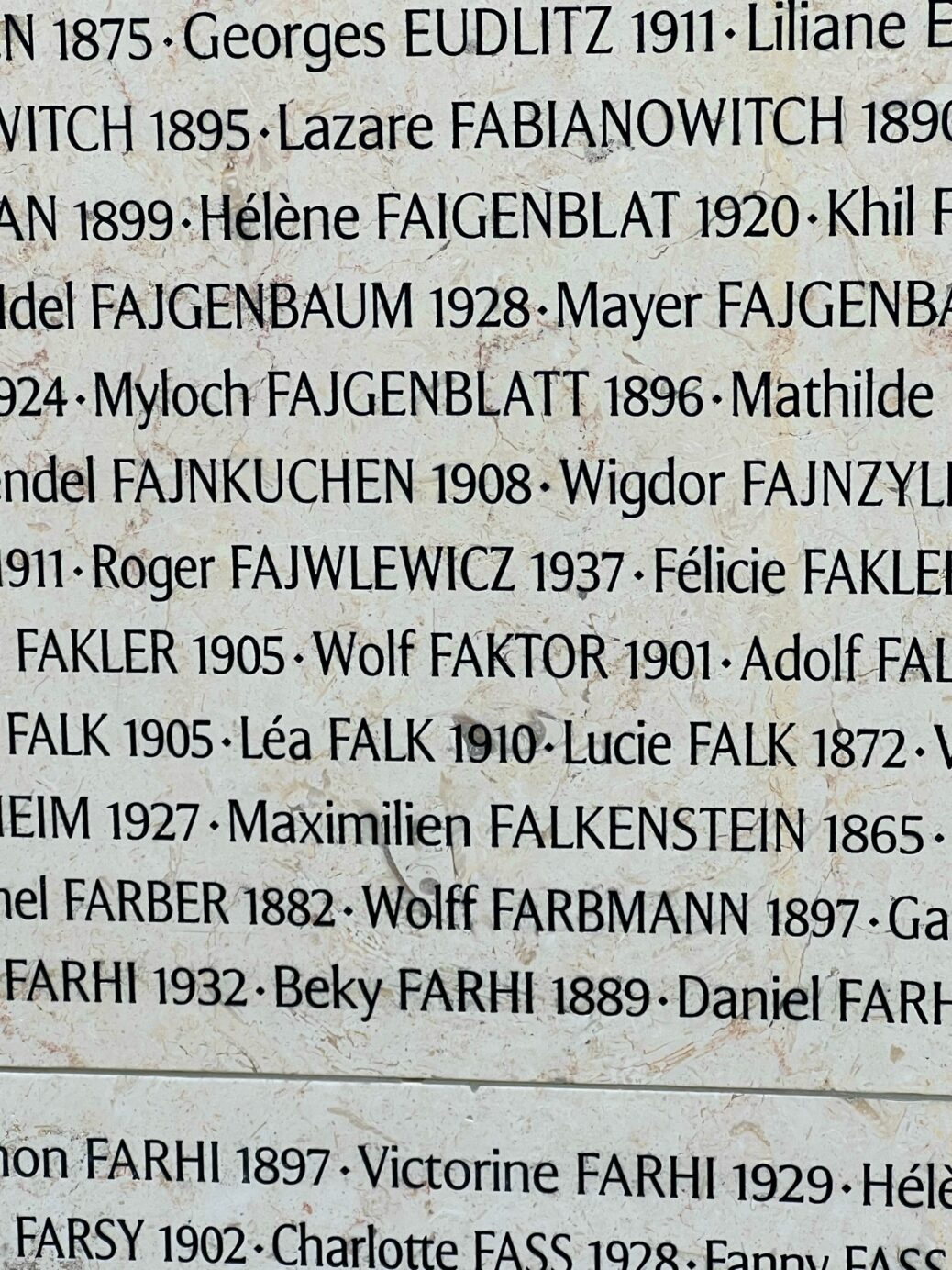

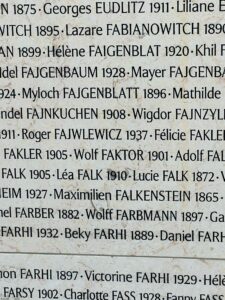

Wolf Faktor’s name is inscribed on the Wall of Names at the Shoah Memorial in Paris

Photo taken by Jennifer Ghislain

Wolf Faktor’s time in the camps

When the train arrived in Auschwitz, the selection process took place. There are very few records relating to this, but Wolf Faktor passed the selection and was sent into the camp for forced labor. He worked in the Auschwitz-Monowitz camp, which was associated with the Buna rubber plant owned by the IG Farben group. The prisoners were forced to work in terrible conditions, and the mortality rate was high.

The next trace we found of Wolf Faktor was in the prisoner lists from the Gross-Rosen camp, which was annexed to the Sachsenhausen concentration camp in Germany. Lastly, we found a record of him in the records from Buchenwald, again in Germany, where he arrived on February 10, 1945 and was assigned prisoner number 125019. In the Arolsen archives’ records for this camp, he is listed as a French Jewish political deportee, although he was actually a Polish citizen.

We also noticed that he gave a false name, saying he called was Victor Facteur. He never identified himself as a Jew, however, but stressed that he was a deported because he was a member of the Resistance. Of all the records we examined, the Buchenwald list is the only one that states that he was Jewish. The records also say that he was transferred to Dachau at some point. The transfer date is not listed, but it must have been before April 11, 1945, when Buchenwald was liberated. We do know his Dachau registration number, however, which was 112442. The reason that he was transferred from camp to camp was that the Soviet troops were advancing towards Auschwitz, which they liberated on January 27, 1945. The deportees were thus moved to other camps further west. Some of the them were forced to walk until they died of exhaustion, on what became known as the “death marches”. We do not know under what conditions Wolf Faktor was transferred from each camp to the next, but the fact that his name is on transport lists suggests that he travelled by train.

The American army liberated Dachau on April 29, 1945. Wolf Faktor, who was suffering from tuberculosis, was repatriated to France due to ill health on June 21, 1945.

After the liberation: a life of petty crime and his quest for recognition

Even as a teenager, Wolf Factor was exposed to the horrors of war. He was reported and arrested repeatedly during the Second World War, but managed to escape several times. His subsequent life as a petty criminal, during which he was arrested and fined for a range of different offences, was full of ups and downs, often involving playing cat and mouse with the law. This made his quest for recognition all the more difficult.

Wolf Faktor first came to the attention of the police on April 20, 1935, when he was charged with assault and battery at the police station in Grandes Carrières, in the north of Paris. On February 15, 1944, he was sentenced to 3 months in prison and fined 2,400 francs for handling stolen goods. This background in petty crime probably proved useful to him during his time in the Resistance and helped him to escape so often: he knew how to keep out of sight and where to find firearms, and was used to living in the shadows.

After the war, on February 10, 1947, he was convicted of assault and battery and carrying an illegal firearm, for which he was fined 1800 francs and given a 4-month suspended sentence. Then on November 18, 1949, he was given a 2-year suspended sentence and a huge 300,000-franc fine for having been involved in handling stolen goods. The French general intelligence service also had him under surveillance. In their report of October 1951, they wrote: “As far as this foreigner’s loyalty is concerned, there is no reason to suspect him, although there is reason to have serious concerns about his behavior and morals. He was, in fact, portrayed as an individual capable of the worst types of violence and devoid of any scruples in his business dealings”.

After he was repatriated from the Dachau concentration camp in 1945, Wolf Faktor fought long and hard for public recognition of his dedication to the country and the sacrifices he made during the Second World War. His involvement in the Resistance, through operations such as arranging for soldiers to desert and supplying weapons to opponents of the Nazis, highlights his commitment to the struggle for freedom. Lastly, his quest for public recognition, including his application to be naturalized as a French citizen and his desperate desire to be acknowledged as having been deported as a Resistance fighter, shows how determined he was to make a place for himself in post-war France.

Wolf Faktor was not recognized as a deported resistance fighter immediately after the war due to his having used various different names and his criminal record. On September 6, 1949, the Paris police chief recommended that he be refused French citizenship and also that his trader’s card be withdrawn. Wolf Faktor compiled several further applications to be recognized as having been deported as a member of the Resistance. In 1951, both the Ministry and a Mr. Gallot, the head of the deported persons bureau, officially approved his application. Camille Nicolas, who we have previously mentioned and was a Knight of the Legion of Honor, supported him in his efforts by testifying to his role in the Resistance. The entire procedure took over six years and entailed multiple attestations and police investigations to verify his story. This illustrates how determined he was to be recognized as a Resistance member. We found no further trace of him after this record from 1951.

What makes Wolf Faktor’s story particularly intriguing is just how convoluted it is. He was not without his faults, nor a hero, given that he was convicted of a number of offenses after the war. Nevertheless, his commitment to the Resistance and his will to live make him a fascinating character. By retracing Wolf Faktor’s story, we had the opportunity to immerse ourselves in one of history’s darkest chapters, and to gain an insight into the motives and sacrifices made by people, both French and foreign, who strove to overcome oppression.

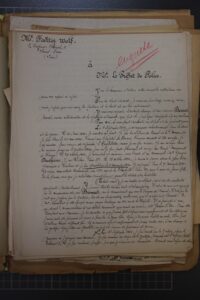

Wolf Faktor’s letter to the Paris police chief, dated March 3, 1947

Transcription of Wolf Faktor’s letter

Wolf Faktor,

2 Impasse Choisel, 2,

Saint-Denis,

(Seine)

To the Chief of Police,

I would like to draw your kind attention to my case, as described below.

For the sake of clarity, it will be rather long, for which I apologize, but I hope you will have the patience and kindness to read it in its entirety.

I wish to inform you of the extraordinary behavior of a man named Marcel Bonnet, a former Gestapo collaborator and the main author of my misfortune. In order to do this, we must go back to the beginning of the war.

On September 4, 1939, I enlisted voluntarily for the entire duration of the war. On May 10, 1940, I was deployed to the front. I defended the Canal de la Marne, where I was wounded on May 23, 1940. Evacuated to Rennes hospital, as Rennes had recently been occupied, I escaped to try to go to England, but I failed to make it. I hid in the surrounding area until July 5, 1940, when I was taken prisoner and sent to Camp Marguerite in Rennes.

On October 26, 1940, I escaped again, with the help of a fellow prisoner, Mr. Georges Duchêne, of 7 rue Lécluse, Paris 17th, and then on October 28, 1940, I managed to cross into the free zone. I made it to Toulouse, where I was demobilized on November 2, 1940. I returned to Paris on November 9, 1940. I resumed my sales business at 152 rue de la Chapelle, Paris 18th, under the maiden name of the woman I had been living with before the hostilities broke out.

As an escaped man, I felt I was at fault in the eyes of the occupying authorities. Naturally, I was unable to access any food ration cards. It was then that I met Squire Bonnet, who I knew only by his first name, Marcel. I only found out later from the Gestapo, after he betrayed me, that his surname was Bonnet. At the time, this gentleman was working as a baker’s boy at 162 rue de la Chapelle. He introduced himself to me as the so-called(!) secretary of a Communist cell based at Cité Jeanne d’Arc, Paris 13th. Trusting this gentleman, I told him what I had done since I joined the army, and how I had helped prisoners of war cross into the free zone. And how I had dressed them up as civilians, as he had witnessed on several occasions.

At that point, with sufficient evidence against me, [Marcel Bonnet] reported me to the Gestapo. He said I was a Gaullist, a Jew and a prisoner-of-war smuggler.

On September 23, 1941, I was arrested by the Gestapo in the store where I was plying my trade. I was taken to the Gestapo headquarters on Avenue de l’Opéra, in the Hotel Edouard 7, where I was manhandled and beaten in an attempt to make me betray my colleagues. When I refused to tell them anything, I was sent to the Cherche-midi prison. I stayed there until January 22, 1942.

During my stay in this prison, Squire Bonnet became my ex-girlfriend’s lover. They lived in my apartment, at 8, cité de la Chapelle, Paris 18th. They took advantage of my absence to rob me of all my possessions, money, furniture, jewels and goods, amounting to 1 million 782 francs. Squire Bonnet even had the audacity to work in my store using my business registration.

I was then taken to the St Quentin camp in the Aisne department, Frontstalag 204.

There I met Lieutenant Ovajor Shadouque, a camp doctor who worked for the 2nd Bureau. He made enquiries about me and tried everything he could to get me discharged, so that I could continue my work with the Resistance. Unfortunately, he was unable to get the German authorities to satisfy his request.

On April 28, 1942, I escaped from the St Quentin camp and headed back to Paris.

As my store had been robbed, there was nothing left. Mr. Bonnet had moved everything to 5 rue Ernest-Roche, Paris 17th, with the help of my ex-girlfriend.

I reclaimed my apartment at 8 cité de la Chapelle. Mr. Bonnet got in touch with the husband of the concierge, Mrs. Albert Brionde. I have no idea if this came about by chance, but Mr. Bonnet found out that I was hiding some incriminating papers in a bungalow belonging to Mrs. Brionde. He had been forced to reveal this because my ex-girlfriend threatened him, so he said(?). Nevertheless, he did warn me, and I immediately decided to go to Gassounville with his wife, Mrs. Brionde, to fetch my papers, or even destroy them. When we got there, we were surprised to hear from Mrs. Brionde’s mother, who lived in the bungalow, that my ex-girlfriend had already been there, along with Mrs. Bonnet’s mother, to fetch the papers and give them to the Gestapo.

On May 9, 1942, I was arrested again and taken to the Avenue de l’Opéra, where they showed me my papers. I was interrogated, confessed to nothing, and stated that the papers did not belong to me, other than a few with my name on them. I was then confronted by Squire Bonnet, who declared that the papers were indeed mine. When I refused to answer, I was beaten and tortured for 3 and a half hours. I was then taken back to the Cherche-midi prison, from where I was taken to Chartres prison and then deported to Germany.

In the meantime, I approached the camp’s legal advisor to ask the judiciary police to do whatever was necessary to stop Mr. Bonnet from trading, as he was still using my store and business registration.

On July 23, 1943, thanks to the intervention of the Swiss international commission, I was released on health grounds due to “tuberculosis”. I was admitted to the Charasse hospital in Courbevoie (Seine department) and then to the Val de Grâce hospital, from where I was discharged again on October 30, 1943.

Mr. Bonnet, with the help of a former police inspector, Mr. Morin, then had me deported for political reasons. Back in Germany, I spent time in the deadly camps, Auschwitz, Buchenwald and Dachau.

When Germany began to face defeat, Mr. Bonnet, like all the militiamen, headed for Germany, only to be repatriated later on as a so-called political deportee, when he realized that Germany and the collaboration were finished.

So, those are the facts. I hope, dear Police Chief, that you will take advantage of all the above information, and do whatever is necessary to conclude my case.

I would also like to give you the name of another man who also complained about Mr. Bonnet’s wrongdoing, and who was imprisoned for 6 months.

Mr. Gidet, 30 rue Berzélius – Paris 17th.

Also the names of some witnesses regarding my case.

Mr. Creux, police officer, 47 rue Doudeauville – Paris 18th

Mr. Alruth, concierge of the building where I had my store, 152 rue de la Chapelle – Paris 18th

Mr. Catays, 63 rue de la Chapelle – Paris 18th

Mr. Pierre Cazaux, police brigadier, 6 cité de la Chapelle – Paris 18th

Thank you in advance,

Yours sincerely

Letter transcribed by Tiago Figueiredo-Biton

Sources

- File on Wolf Faktor, Victims of Contemporary Conflicts Archives Division of the Ministry of Defense Historical Service, in Caen.

- File on Wolf Faktor, Bad Arolsen

- File on Wolf Faktor, Paris police headquarters

- Wolf Faktor’s internment record from Drancy camp, Shoah Memorial in Paris.

Bibliography

- Alexandre Bande, Pierre-Jérome Biscarat and Olivier Laleiu (dir.), Nouvelle Histoire de la Shoah (New History of the Holocaust), published by Passés composés, Paris, 2021.

- “Mille ans d’une nation, la Pologne” (A thousand years of a nation, Poland), L’Histoire special issue, January 2024

Websites

- Convoy 77 nonprofit association

- Mémoire des hommes (Memory of Men, in French only)

- Shoah Memorial, Paris

- “Camille Nicolas”, Wikipedia (in French)

- “Ceux de la Résistance”, (“Those of the Resistance”) Wikipedia

- “The Polish-Soviet War”, Wikipedia

- “The Polish Army in France (1939–1940)” Wikipedia

We would like to thank the following people for their invaluable help with this project:

Lucie Pitiot, the Principal and Magali Sauquet, Assistant-Principal of our high school for their support throughout the project, Anne Kobylak (Radio DiVa 14), Mathias and Claire (Radio DiVa14), Marie Moutier-Bitan (historian), Claire Podetti (Convoy 77), Claire Stanislawski (Shoah Memorial archives department), and also the teams at the Shoah Memorial in Paris and Drancy and at the former Bobigny station.

CNRD prizegiving ceremony

The 12th grade students from class TG3 at the François Villon high school in Paris (2023-2024 school year) : Agathe Babin, Martina Ben Ben, François-Henry Bergès, Sadia Bouzouma-Sarrazin, Marvin Da Silva, Sara Deric, Tiago Figueiredo-Biton, Adja Karamoko, Souad Kissi, Paul Moity, Laeticia Pereira-Nadais, Laetitia Romanos Frontin, Eve-Lucy Rouly, Roman Viruega and Alyssia Walbert, with Jennifer Ghislain, thier history and geography teacher and Gabrielle Bour, teacher and documentalist.

Français

Français Polski

Polski