Berthe STEINSCHNEIDER

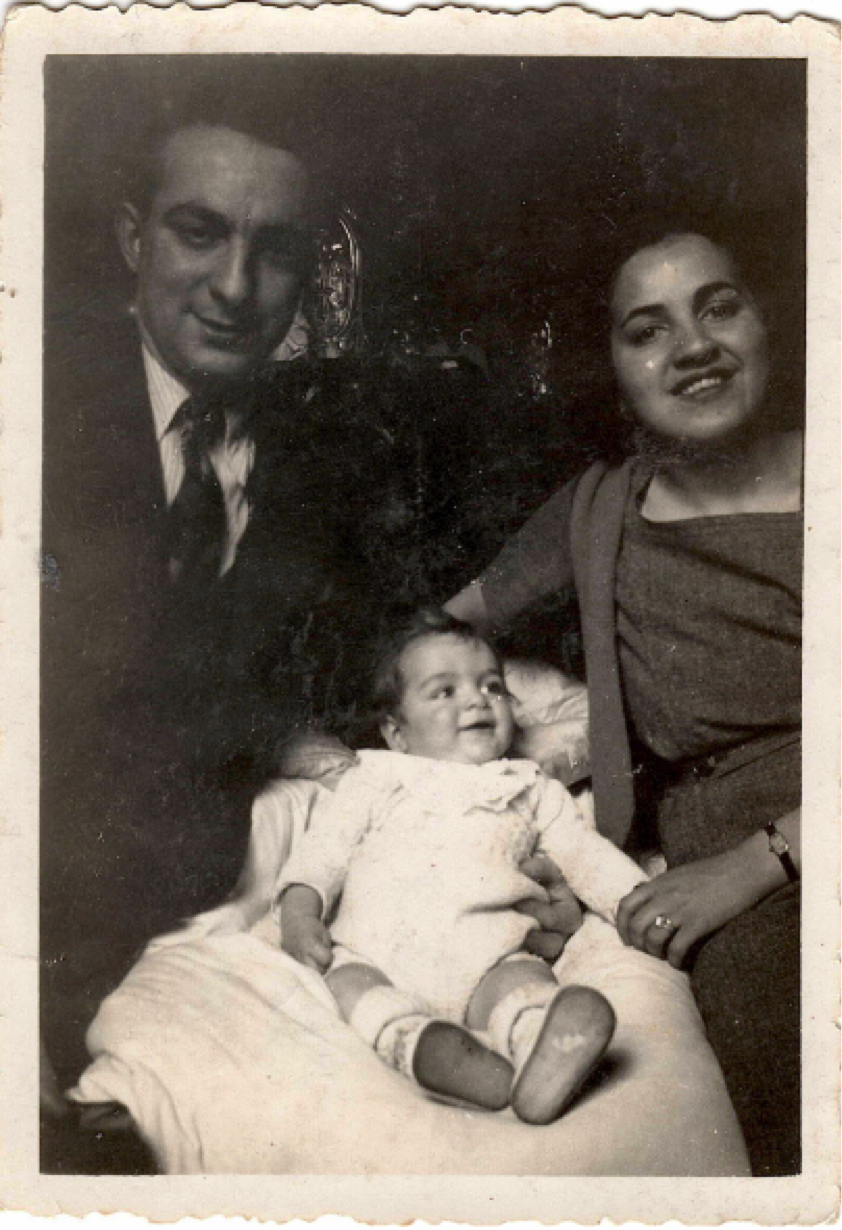

Photo of Berthe, her husband David and her son Robert,

Ms. Brulant’s family archives

Berthe, who was deported on Convoy 77 on July 31, 1944, was among the thousands of people whose lives that were turned upside down during the Second World War, when millions of European Jews were exterminated. This is the biography of a woman whose life story embodies both tragedy and great resilience.

In common with countless other people, Berthe was robbed of her normal life, her family and her future by the Nazi atrocities. Our aim, in writing this biography, was to retrace her journey, to bring life to her story, and to learn more about the destructive impact of deportation. We wanted to pay tribute to not only to Berthe but also to all of the other Holocaust victims by charting the various stages of her life, from when she was a child to when she was arrested, deported and eventually returned to everyday life. We drew on a number of sources, including a meeting with Berthe’s niece, Ms. Brulant, and a written account from her granddaughter, Gaëlle Moreau. We also split up into smaller groups to work on gaining a better understanding of who she was and what she went through.

All our research into Berthe has made us more aware of how monstrous the Nazis’ treatment of the Jewish people really was. We have come to realize that, throughout history, so many people have been less fortunate than us. Even this indirect encounter with someone who lived through these historical events gave us a real sense of the impact it had on the lives of everyone who experienced it. We no longer think in terms of deportation statistics, but in terms of individual lives. These life stories have made us aware of the trauma that not only the deportees, but also their whole families experienced. We came to realize that the events we study in class really did happen. Berthe’s story shows not only how people can rebuild their lives, some more easily than others, and look forward to the future, but also how the after-effects continue to be passed down through the generations. Gaëlle Moreau, who kindly agreed to share some information about her grandmother, did so only with great emotion and trepidation, for fear of betraying both her grandmother’s and her father’s silence during their lifetimes. Therefore, while we have a duty to remember, we also needed to ask ourselves how this duty should be fulfilled. Was it really necessary to know everything about Berthe’s life and to recount every detail? At the end of the year, we still had a number of questions that left room for doubt. The gaps in our biography also remind us of all the people who vanished without trace, and about whom no one knows anything at all.

We would therefore like to express our warmest thanks to Ms. Brulant and Ms. Moreau for all the information that they kindly shared with us.

Biography of Berthe Steinschneider

Berthe Simplatt was born at born at 5 a.m. on November 16, 1913, in the 13th district of Paris. Her parents were Rebecca Gleimann, a housewife, and Wolf Simplatt, a cap maker, who were 24 and 27 years old respectively when they daughter was born.

When Berthe was three years old, her parents moved to England to work and be nearer to their family. Mr. and Mrs. Plescoff, her maternal aunt and uncle, who unable to have children of their own, agreed to take care of Berthe. She therefore grew up in Paris.

She married David Steinschneider, who worked in the fur trade, on June 4, 1936, at the town hall in the 3rd district of Paris; the wedding reception was held at the Lutetia Hotel. They set up home at 64 rue de Belleville in the 10th district of Paris. The following year, on August 29, Berthe gave birth to their son, Robert.

Berthe and David on their wedding day

Ms. Brulant’s family archives

David was drafted into the French army in 1939, but returned to civilian life after Germany defeated France. He moved back in with his wife, who was no doubt glad to have him back, and their son.

In 1940, the family went on vacation to England to visit Berthe’s sister, Charlotte (possibly without David?). According to Gaëlle Moreau, they took the last ferry back from Dover, just before maritime links between England and France were suspended due to the war. France had been defeated by the time they got home and the Germans had occupied Paris. After the armistice was signed on June 22, Marshal Pétain met Adolf Hitler in Montoire and agreed to collaborate with the Germans. Soon afterwards, anti-Semitic restrictions were introduced in Paris. Jews were only allowed out at certain times, were banned from going to many public places, were only allowed to ride in the last subway car, and were banned from working in influential professions.

Xavier Vallat was appointed to lead the French government’s Commissariat aux Questions Juives (Commission for Jewish Affairs), which was responsible for confiscating Jewish assets. Berthe’s father-in-law, Chaïm, was one of the victims of this policy. In 1941, at the behest of the Germans, the Vichy government founded the UGIF (Union Générale des Israelites de France, or General Union of French Jews), which was intended to centralize control of the Jewish population and provide social assistance. All Jews had to join the organization, (including Berth, whose 1943 membership card, which was stamped in 1944, is held at the Shoah Memorial in Paris). Many families needed help as a result of spoliation. Most of the Jews’ names and addresses were already known to the authorities because they were all supposed to have registered themselves during a special census in 1940. The authorities used the census lists to help plan the roundups, which began in the spring of 1941 with the “Rafle du Billet vert” (Green Ticket Roundup), during which 3,700 foreign Jewish men were sent green slips summoning them to their local police stations. They were then arrested and transferred to the Beaune-la-Rolande and Pithiviers camps, and from there they were deported to the Auschwitz concentration camp in occupied Poland. They included Berthe’s brother-in-law Maurice (Mowsza) Sztejnsznajder, who was married to David’s sister Marinette, and their cousin Chaïm Sztejnsznajder, both of whom survived their time in the camps.

During the Vel d’Hiv roundup in July 1942, Henri (Hersch) Steinschneider (David’s elder brother, who had not become naturalized as a French citizen at the same time as the rest of the family, in 1926), together with his wife Rose and their six-year-old son Daniel, were all arrested. At this point, Berthe, in common with many other parents, realized that even children were being arrested. Urged on by her husband David, she therefore agreed to send her son Robert into hiding. A communist who she did not know took him away and then Marcel and Denise Vivier, who lived in Cléry-Saint-André, in the Loiret department of France, took him in. This suggests that Berthe and/or David may have been Communists themselves, or at least involved in some way with the party and its network.

It was not long before some other of their family members were arrested. In October 1943, David’s father Chaïm and Rose and Henri’s daughter Raymonde (Rachel), who had escaped the round-up in July 1942 and was by then living with her grandparents, were arrested. David’s mother, Genendel, who was sick, was left at home alone. Berthe and David went to see her, and this was what prompted the Germans to search their home. On July 21, 1944, they too were arrested, on the grounds that their son was not at home. In reality, this was just a pretext: they were arrested simply because they were Jews.

They were initially taken to the police station on rue des Saussaies and from there to Drancy camp. When they arrived, the authorities confiscated the 10,000 francs that they had on them. Drancy was a major internment camp north-east of Paris. When the Germans first took over the camp in August 1941, their main objective was to intern more than 4,000 recently arrested Jewish men from Paris. Originally built in the 1930s as a low-income housing complex, Drancy was once used as a prisoner-of-war camp. As of 1942, it became the main transit camp for Jews who were to be deported. Living conditions in the camp were far from ideal.

While they were interned at Drancy, Berthe and her husband David sent two letters to their family. The first letter, dated July 22, 1944, said they were in good health. The letters suggest that Berthe and David may have been allowed to receive some parcels, and hoped, at least to begin with, that they were not going to deported. They asked David’s sisters to send them things such as toiletries: soap, toothpaste and toothbrushes, as well as handkerchiefs, clothes, blankets and cigarettes. They also said they had not had time to take much with them because they had left home without warning. They asked that parcels be sent to them via the UGIF. They also warned David’s sisters that the Germans were after their mother, and had arrested them so they could keep her safe. They were also worrying about their son Robert, although they had not told the Germans where he was. In their second letter of July 30, 1944, they tried to put their families’ minds at rest about the living conditions in the camp, and said they would be leaving the following day. David and Berthe were full of praise for the camp food: vegetable soup, coffee in the morning, wine twice in one week, meat once a week, and over eight days they had been given a spoonful of jam, an ounce of cheese twice, and almost two ounces of butter each. No doubt they were trying to make out that everything was fine, so as not to worry the family. Two days before they left, they said that they were both sleeping in the same room, that they were able to keep clean by taking cold showers and even hot showers twice a week. Only at the end of the letter did they broach the most important subjects. David asked the family to go to their apartment, on the quiet, to pick up anything that was worth salvaging. He also told the family where Robert was, so they could send ration coupons for him. To that end, David said they could also collect any wages still due to him.

On July 31, 1944, Berthe and her husband were deported on Convoy 77 to Auschwitz-Birkenau. Berthe was selected to enter the camp to work. She remained there until October, when she was sent to Kratzau until May 9, 1945, when the camp was liberated. In Kratzau, now Chrastava, in the Czech Republic, the prisoners worked in weapons factories.

As for David, he too was selected to go into the Auschwitz-Birkenau camp to work. After that, there are records of him on January 29, 1945 in Sachsenhausen, on February 17 in Mauthausen and on March 23 in Amstetten. He was seen alive (for the last time) in Linz on April 16, 1945. He was not repatriated to France because he had typhus when the camp was liberated. There is no further trace of him after that.

Berthe was repatriated to France via in Longuyon, near the Belgian border, which was one of the main reception centers for returning deportees. From there, she travelled by train to Paris, where she arrived at the Gare de l’Est station on May 22, 1945. When she got back, she tried to find out what had happened to her husband, but David never made it back from the death camps.

Berthe’s time in the camps left her extremely weak: she lost around 33 pounds and, in 1944, had caught scarlet fever. According to the medical report after she was examined when she got back to France, Berthe, like many women deportees, was suffering from amenorrhea. She also needed some dental work. This all goes to show just how brutal deportation was, leaving people with lasting physical symptoms as well as psychological scars.

When Berthe returned home, she had only one thing on her mind: to find her son. She just hoped that he had survived. It was an emotional reunion, and Robert was in good health. However, Berthe, like many deportees, was still traumatized by what she had been through. Unable to raise Robert on her own, she asked her sister Charlotte to take care of him for the next two years.

Berthe was able to reclaim the apartment on rue de Belleville and resume her life… but she missed her husband, David, immensely. Perhaps she felt guilty because she had survived while he had not. She had to apply to the courts to be declared a widow. David was very sick when he was liberated, but there was no death certificate and no proof that he had died. This meant that Berthe had to rectify her matrimonial status. She requested a review of his case in 1948, and on December 9, 1949, the court ruled that David was dead. As it was unclear when or where his death occurred, he was initially declared to have died at Drancy on July 31, 1944. (Much later, according a decree dated April 25, 2003, he was officially declared to have died during deportation on August 5th, 1944, i.e. soon after he first arrived in Auschwitz. This was the case for many deportees whose dates of death were unknown). We can only suppose that this helped her to grieve and start to move on with her life. We know that after that, on May 31, 1950, Robert was made a ward of the State and this was noted on his birth certificate. That was not the end of the matter, however. In 1954, both David and Berthe were recognized as having been “political deportees”. As a result, in 1956, the words “Died for France” were noted on David’s death certificate. This meant that Robert, who was almost 20 years old by then, was exempt from military service in North Africa, and his mother was happy that he would not have to go to Algeria. It also meant that she was entitled to a widow’s pension from the French Ministry of the Armed Forces.

Little by little, Berthe rebuilt her life as best she could. She met a Polish widower, Chaîm Flamenbaum, who was born in Kielce, Poland. He had lost his wife and both of his daughters in the extermination camps. He had been interned it Drancy on July 18, 1942, deported to Auschwitz on July 29 and subsequently transferred Mauthausen. In March 1945, he was transferred to Amsteten. He was liberated on May 5, 1945 and repatriated to the Lutetia Hotel in Paris on May 19. Did their tragic experience bring them closer together? They decided to get married, but this raised the question of Robert’s guardianship. They had to have a meeting with a family counsellor and representatives of both sides of the family before Chaïm could legally become Robert’s joint guardian. The counsellor referred to the fact that “his administration has always been wise and prudent, and [that Berthe] shows the utmost affection for her child”. On February 9, 1953, it unanimously agreed that the future spouses should share Robert’s guardianship.

They were married on March 21, 1953 in the town hall of the 10th district of Paris. David’s family were not happy that Berthe remarried so soon; they felt that she should have mourned David for a while longer. They distanced themselves somewhat from her. Although Robert kept in touch with his father’s family, Berthe had very little contact with them. Meanwhile, Berthe and Chaïm opened a tailoring studio near their apartment.

In order to piece together what happened in Berthe’s life after she returned from the camps, we contacted her granddaughter, Gaëlle, and added her recollections to those of Berthe’s niece, Ms. Brulant. Robert, who was Berthe’s only child, married Solange Schwarz and Gaëlle was their adopted daughter. To this day, she is still affected by the experiences of the previous generations. As we read her story, we soon realized that she had been told very little about what happened during the war, and that she had never really dared to ask about it, feeling that it was a taboo subject. She may have been afraid of upsetting her father and grandmother, or of forcing them to relive their trauma. At the end of the account she kindly wrote for us, she closed with: “She didn’t want me to cry, she wanted me to live”. A testimony brimming with hope.

Berthe on June 19 1999,

Ms. Brulant’s family archives

Berthe passed away on February 15, 2001. She lived a long life, and watched her son and granddaughter grow up. She was delighted to be able to go to Gaëlle’s and Antoine Moreau’s wedding on June 19, 1999.

Français

Français Polski

Polski