Clara (Eugénie) ILZICER

This biography was written by Ariane Rocher, Rose-May Brossollet, Théophile Knecht, Siméon Hellier, Arthur Fonrose, Jean-Baptiste Blanc and Lucian Anger.

From childhood through to marriage

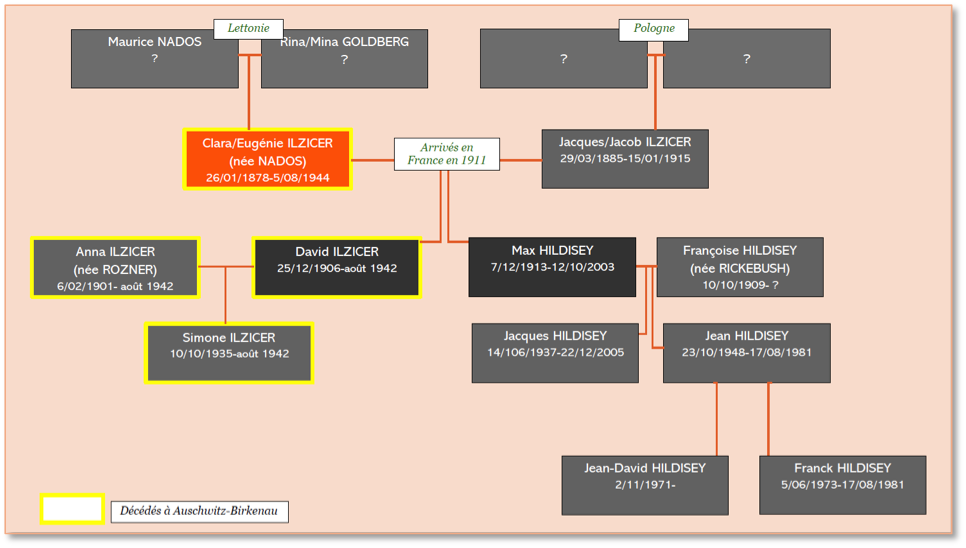

Clara Nados[1] was born on January 26, 1886[2] in Dvinsk (now Daugavpils) in Latvia, a town which at that time was in the Russian empire. She was the daughter of Maurice Nados and Rina/Mina Goldberg, and came from a Jewish family in Latvia, but to date, her family background and her parents’ situation are unknown.

The Nados family was Jewish, and almost certainly experienced intense anti-Semitic discrimination under Tsarist rule. It was this violent, legally-allowed anti-Semitism that made life so difficult for Jews, and prompted the large-scale emigration of Jews from Central Europe to France: between 1881 and 1925, some three and a half million Jews left Eastern and Central Europe, among them the Nados family.

While we still know nothing about Clara Nados’ early life in Latvia, we do know that she traveled to Warsaw, in Poland, where there was a large Jewish community and where, “under Hebrew law”, she married Jacob/Jacques Ilzicer[3], on December 26, 1908[4].

The move to France: an escape from oppression

In common with the majority of Jews from Eastern and Central Europe, Clara and her husband fled not only the oppression and pogroms in Russia and the Austrian Empire, but also the dire economic climate in the region, which affected Jews more than the rest of the population.

As we shall discuss in greater detail later on, it is possible that the couple spent some time in London, and had their first child there, before they moved to Paris.

In 1911[5], they arrived in France, which was the first European country to gain independence, as a result of the French Revolution. People therefore felt that it was the “ideal” country to emigrate to. It was also chosen because refugees were generally accepted and made to feel welcome.

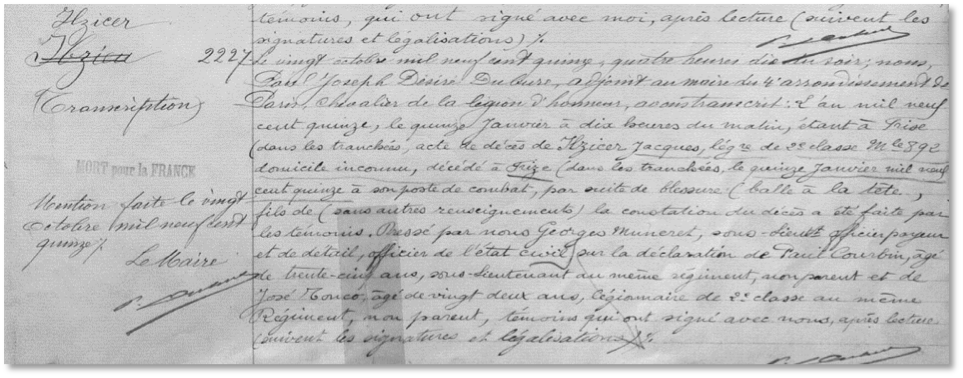

The couple, like many others, settled in Paris, a city where they could find work and become involved in political and cultural life, and where tens of thousands of Jews from Central and Eastern Europe lived. Their son Max was born on December 7, 1913, and his birth certificate lists Jacob/Jacques as a “commissionaire”, (a messenger or delivery man) but gives no further details[6] and Clara as a housewife, meaning that she did not go out to work. They were probably fairly poorly off. They were living at 20 rue de l’Hôtel de Ville, in the 4th district of Paris at the time[7].

During and after the First World War

On August 3, 1914, Germany declared war on France, and the whole nation was drawn in. Jacques decided to join the French army, as did 30,000 other foreigners, including 8,500 Jews. In doing so, these foreign volunteers expressed their commitment and gratitude to their adopted country. He fought in the 3rd infantry regiment of the 1st foreign regiment, which included 2,200 soldiers who had migrated to France. Between 1914 and 1915, he fought in the same regiment as the well-known Swiss writer, Blaise Cendrars.

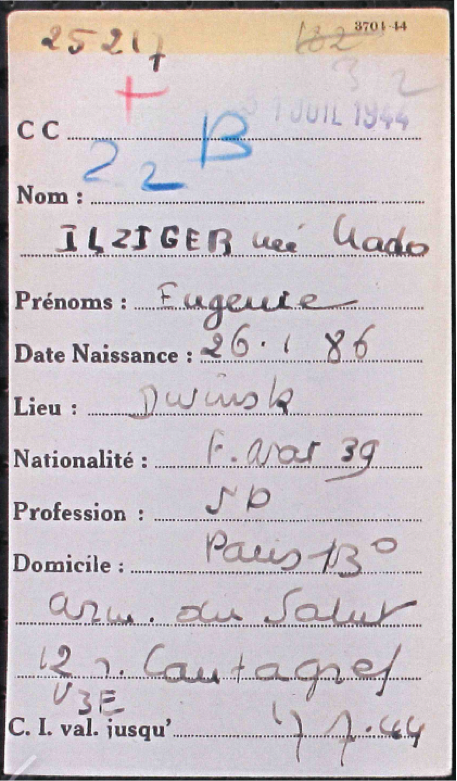

Jacques Ilzicer died at 10:00 a.m. on January 15, 1915, in the village of Frise, on the Somme. He was 29 years old. His death certificate, which is held at the town hall in the 4th district of Paris, states that he died in action “on duty, in the trenches, as a result of his injuries (a bullet to the head)”.

Jacques Ilzicer’s death certificate

Paris digital archives

The death certificate gives no information about his ancestry: it only says “son of (no details)”. This means that we have no way of finding a link between him and any of the other people with the surname Ilzicer who lived in Warsaw at around the same time as him.

Clara Ilzicer thus became a war widow, and had to bring up their son Max on her own. In March 1918, there was an explosion in their apartment building[8], but we do not know if Clara and her son were still living there at the time. However, in the 1926 census listing for 20/22 rue de l’Hôtel de Ville, the head of the household in one apartment was David “Ulzitzer” who was born in London in 1908, had become naturalized as a French citizen and worked as a printer. There was also a Max Ulzitzer, who was born in Paris in 1913, and was listed as a “relative”. Clara herself was not listed, but it seems likely that the surname Ilzicer was spelled incorrectly and that David and Max were indeed her sons. We found a marriage certificate for a David Ilzicer dating from 1934[9], which states that he was born in London on December 25, 1908, and that he was the “son of Jacques Ilzicer, deceased”, and “Eugénie Nados, laundress, widow, living at 41 rue de Caen in the 12th district”. This is what leads us to believe that Jacques/Jacob and Clara/Eugénie may spent some time in England between when they left Poland and when they arrived in Paris. But the dates do not exactly add up here: how could they have had a religious wedding in Warsaw on December 26, 1908 if their son was born in London on December 25, 1908?[10] ? It is also odd that they named both of their sons David. However, if we look closely at the birth certificate of the child born in 1913, we see that the name Max was written in the margin. Also, in most post-war records, the second son is listed as “Max”. The “acte d’individualité” (in France, an “act of individuality” is a certificate that confirms that a person whose names have been written in a different order on official documents is in fact the same individual) drawn up in 1922 may provide the answer: the first name is given as Max, and the second as David[11]. It appears that the name Max was accidentally left off the birth certificate, so was added as a note in the margin, and in fact the child’s middle name was David.

Acte de naissance de Max Hildisey, fils de Clara et de Jacques Ilzicer,

Archives numérisées de Paris

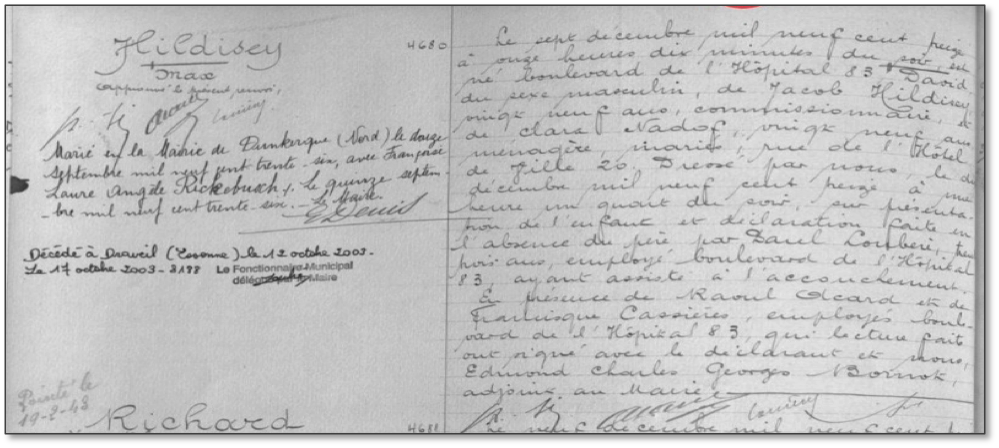

En 1922, veuve de guerre, Clara peut prétendre à une pension, même si elle est n’est pas naturalisée française[12]. Il était donc indispensable d’établir ce document visant à établir que Max Hildisey est bien son fils et celui de Jacques Ilzicer « mort pour la France », la confusion sur le patronyme lui ayant peut-être valu un refus en première intention. Clara engage par conséquent une démarche juridique pour faire reconnaître son fils Max Hildisey comme la même personne que Max Ilzicer, et recevoir par la même occasion une pension d’orphelin. Du fait de son incapacité à lire et écrire en français, Clara rencontre des difficultés pour effectuer l’acte de notoriété et d’individualité de son fils. Nous ne savons pas pour quelle raison le nom familial a été modifié de « Ilzicer » à « Hildisey » sur l’acte de naissance de Max[13], mais on peut supposer une orthographe fautive commise par l’administration, certainement induite par une prononciation approximative en français d’un patronyme étranger. Effectivement, on y trouve l’orthographe Hildisey tant pour le père, Jacob, que pour le fils. On note également une erreur pour le nom de famille de la mère qui est « Nadof » sur l’acte. Le patronyme « Ilzicer », attesté en Pologne n’est visiblement que peu porté en France et source d’erreur. En effet, on constate sur le livret militaire du père que son nom est tout d’abord mal orthographié, puis barré et remplacé par le nom correct.

Jacques Ilzicer’s army service record,

Source: memoiredeshommes.sga.d

efense.gouv.fr

Thus, later in 1922, Clara Ilzicer clearly had an older son, David Ilzicer, then 14, and a younger son, Max Hildisey, whose name was still spelled in that way but who had been officially confirmed to be Jacques Ilzicer’s son.

This also shows that in 1915, when Clara was either 29-30 or 37, she was left a widow with two young children, David, who was 7, and Max, who was only 2, in a country she hardly knew and whose language she could barely speak or write[14]. As a war widow, living alone and in desperate financial circumstances, it was vital that she be able to claim a pension for herself and her two young children.

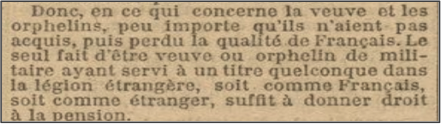

The extract from the French Official gazette below reads: “Thus, as far as widows and orphans are concerned, it is of no importance if they never acquired French nationality or if they then lost it. The mere fact that they are the widow or orphan of a soldier who served in some capacity in the Foreign Legion, either as a French citizen or as a foreigner, is sufficient to entitle them to a pension”

French Official Gazette, March 6, 1919, p. 1046.

Source: gallica.bnf.fr

The 1926 census listing for Jacques and Clara’s previous address only included David and Max. The elder brother, who by then was 18, declared that he was the head of the household, and was a “printer”. Clara is not listed for some reason: might she have been in hospital, living or staying elsewhere, out of town?

Between the wars

On May 5, 1934, David Ilzicer, Clara/Eugénie’s son, married Anna Rozner[15] at the town hall in the 20th district of Paris. At the time, David was a laundry worker and Anna a milliner. They were living at 39, rue de la Mare in the 20th district. The marriage certificate also lists his mother as a laundry worker, although she does not appear to be have attended the wedding. By the time of the 1936 census, they were still living at the same address and in the meantime had had a daughter, Simone, who was born on October 10, 1935 in Paris. David declared that he was working at the Lavoir Sauveur laundry.

On September 12, 1936, Clara’s second son, Max, married Françoise Rickebush in Dunkirk, in the Nord department of France.

On June 14, 1937, Max and Françoise had a son, Jacques[16].

On June 2, 1939, Clara was naturalized as a French citizen by decree[17], At the time, she declared that she was living at 35 rue des jardins Saint-Paul. However, some records list her last address before she was deported as 104 rue/boulevard de la Chapelle. We searched the 1931 and 1936 census records for these addresses but Clara was not listed at any of them.

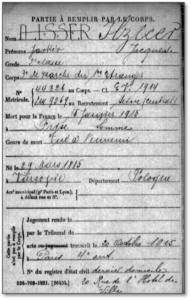

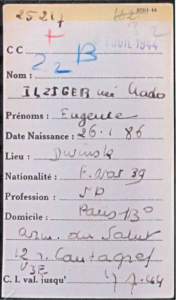

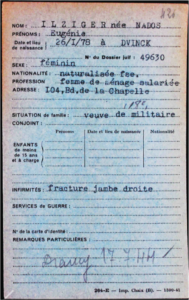

We found no trace of Clara between 1940 and 1944, which probably means that she was living in hiding somewhere. Max was a prisoner of war for 5 years[18] and Clara’s other son, David, together with his wife and their 7 year old daughter, had been deported[19]. There was therefore no one left to help her. Her Drancy camp internment card says that she was rounded up at the Salvation Army shelter at 12 rue Cantagrel in the 13th district of Paris. This was a hostel that took in homeless people or those in difficulty, provided shelter and helped them to reintegrate into society. Clara, who was most likely destitute, must have sought refuge there. Her Drancy internment card and the prefecture record both state that she had been naturalized as a French citizen in 1939, However, given that the Vichy government had revoked French nationality from anyone who had been naturalized since 1927, the fact that she was French meant nothing to the Vichy authorities, and did not prevent her from being deported. The prefecture record also reveals that she was disabled due to a fracture of her right leg. It is impossible to tell if the fracture was recent or, if it had happened a long time ago, it had caused her long-term disability. Another interesting piece of information in the prefecture record is that it lists her occupation as “salaried housekeeper”. As domestic servants tended to live in their employers’ homes, this may explain both Clara’s various addresses and the fact that she was not listed in the census records.

On the left: Drancy camp internment card

French National archives in Pierrefitte, ref. FRAN107_F_9_5702_L

On the right: Paris prefecture record

French National archives in Pierrefitte, ref. FRAN107_F_9_5615_012039_L

Clara rounded up and deported

On July 17, 1944, Clara Ilzicer was rounded up at the Salvation Army hostel and interned in Drancy camp, north-east of Paris. The Germans took over Drancy camp in August 1941 to intern more than 4,200 Jewish men who had recently been rounded up in Paris. In the summer of 1942, it became the main transit camp for Jews who were to be deported from France.

Two weeks later, on July 31, 1944, Clara was deported on Convoy 77. She was assigned prisoner number 37,664. This was the last large convoy to leave France for Auschwitz-Birkenau. The prisoners were taken from Drancy to the Bobigny railway station, where they were loaded onto cattle cars. In addition to the large number of deportees, including very young children, Convoy 77 bore all the hallmarks of a convoy that was put together in a hurry in the face of the German army’s imminent defeat. For example, the deportees came from a wide variety of different countries.

It is not clear how or when exactly Clara Ilzicer died. It may have been during the journey or after she arrived in Auschwitz, but given her age, either 58 or 66, and her disability (caused by her fractured leg, which may or may not have happened recently), there is little doubt as to what happened to her. If she survived the journey, she must surely have been selected to go to the gas chambers as soon as she got off the train onto the ramp at Auschwitz.

MAX’S EFFORTS IN MEMORY OF CLARA

Clara’s legacy did not end there, however. It continued on not only with the birth of her second grandson, Jean-Roger, on October 23, 1948 in Fontenay-aux-Roses, in the south western outskirts of Paris, but also through the tireless efforts of her son, Max, to have the truth surrounding his mother’s death fully acknowledged[20].

From the 1960s onwards, in common with many other family members of murdered deportees, Max embarked on a series of lengthy official procedures to have his mother’s status formalized. On November 20, 1961, he submitted a request for information to the French Office for Deported persons and miscellaneous statuses. This was dealt with several days later, and he received a reply on January 16, 1962.

According to the Office for Deported Persons at the French Ministry of Veterans’ Affairs, after having applied to have Clara’s civil status as a “non-returned person” confirmed, Max was issued with a “disappearance” certificate on April 4, 1962. Max himself was unable to provide any details about what had happened to her because he had been a prisoner of war for five years[21]. But from then on, the French authorities classified his mother as “disappeared”, which was an essential prerequisite for submitting a request to the court for a death certificate.

The various stages of the recognition process

The Seine High Court took several months to examine the case, and eventually issued a ruling on October 19, 1962: Clara was officially declared to have died in Drancy on July 31, 1944. This judgment was forwarded to the Police Headquarters on December 10, and from then on served as her death certificate.

The official acknowledgement of her death[22] enabled Max to continue his efforts.

And so, thanks to her son’s determination, Clara was finally granted the status of “political deportee”, more than five years after his initial application on November 30, 1957. Political internee or political deportee status is granted to anyone who was arrested, imprisoned or deported by the occupying forces for political reasons, i.e. for anything other than a common law offence.

The court approved the request on June 14, 1962, and Max was notified on June 25, 1962. The internment dates taken into account was from July 17 through July 31, 1944, while the deportation dates were July 31 through August 5.

The outcome of Max’s efforts to pay tribute to his mother

The fact that Clara had been officially acknowledged to have died as a “political deportee” led to the words “Died for France” being written in the margin of her death certificate on January 30, 1963. Max then made sure that the same instructions were sent to the town halls in Drancy and the 4th district of Paris, the first being the place where she was declared to have died, the second her last place of residence (the address she had given when she applied for French citizenship).

Lastly, in November 1963, under the terms of decree no. 53-103 issued on February 14, 1953, in accordance with a French law passed on July 19, 1952 on the status of ex-servicemen and victims of war, Max was awarded a compensation payment for families of political internees who had died in detention. As Clara’s descendant, Max received a cheque for 120 francs from the French Treasury: a final gesture from the State to mark the loss of his mother.

The French government is still working on acknowledging what happened to the Jews who lived in France. One thing it is doing is changing some of the death dates that were initially given for deported persons. In 2011, for example, a publication in the French Official Gazette changed Clara’s date of death from July 31, 1944 in Drancy to August 5, 1944 in Auschwitz, which was just after Convoy 77 arrived at the killing center.

Clara was then granted the status of “died during deportation” in accordance with a French law no. 85-528, which was passed on May 15, 1985 and which stipulates that these words be recorded on the death certificate anyone who was deported and died during the Second World War. The changes in death dates significantly increased the number of people eligible for this status. Although it took more than 25 years for this law to apply to Clara, the Ministry of Veterans Affairs is actively pursuing its efforts on behalf of other deportees who are not yet eligible for this status.

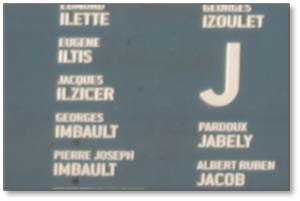

In writing this biography of Clara, we pay tribute not only to her but also to her husband, Jacques Ilzicer, who gave his life for France on the battlefield in 1915. His name, along with those of the 94,415 other people from Paris who died in the war, is engraved on the war memorial on the exterior wall of the Père-Lachaise cemetery, on the boulevard de Ménilmontant in the 20th district of Paris, which was inaugurated on November 11, 2018.

CLARA’S DESCENDANTS

We encountered some difficulties in gathering information about Clara’s descendants. We did, however, manage to contact her great-grandson, Jean-David Hildisey, via the social networks. He is the son of Jean (Roger) Hildisey, Clara’s second grandson. Her first grandson, the only one that she might have known, was Jacques (Georges) Hildisey, who died on December 22, 2005, at the age of 89, in Sens, in the Yonne department of France. Jacques’ brother, Jean (Roger), who eleven years younger than him, died at the age of 32 on August 17, 1981, together with his son, Franck Hildisey, who was just 8[23]. Jean-David, the only living family member that were able to contact, was Franck’s older brother.

Notes and references

[1] Depending on the source, she was also referred to as “Eugénie” or “Clara Eugénie”, “Nados”, “Nadof” or “Nado” and “Ilzicer” or “Ilziger ”.

[2] Clara’s year of birth is unclear. Some records list her year of birth as 1886, others as 1878. However, her son Max’s birth certificate, dated December 1913, states that she was 29 years old, which would mean she was born in 1884.

[3] He was a Polish Jew born in Warsaw on March 28, 1885, but his parents’ names are not shown in the records we have available.

[4] According to the deed drawn up by the notary in 1922, Victims of Contemporary Conflicts Archives Division of the Ministry of Defense Historical Service, in Caen, ref. 21_P_574_365_23400_DAVCC_copyright_0924.

[5] A record from the Paris prefecture dating from 1961 states that Clara arrived in France in 1911, Victims of Contemporary Conflicts Archives Division of the Ministry of Defense Historical Service, in Caen, ref. 21_P_574_365_23400_DAVCC_copyright_0921

[6] A simple job, a “commissionaire” carried various items through the streets and into buildings without elevators, and delivered messages.

[8] On March 30, 1918, during the First World War, a shell fired from a Big Bertha cannon exploded at no. 20 rue de l’Hôtel-de-Ville. We do not know if Clara and her son(s) were still living there at the time. Explosions in Paris that day left 10 people dead and 60 injured, including one at 20 rue de l’Hôtel de Ville. Source Gallica/BNF https://gallica.bnf.fr/ark:/12148/bpt6k4605797h/f1.image#

[9] Paris digital archives, act 714. Marriage on May 5, 1934 of David Ilzicer and Anna Rozner, born in Poland in 1901.

[10] The date of marriage was based simply on a declaration included in a deed drawn up by a notary in 1922, (Victims of Contemporary Conflicts Archives Division of the Ministry of Defense Historical Service, in Caen, ref. 21_P_574_365_23400_DAVCC_copyright_0924), It is therefore possible that the date may be mistaken (unclear diction, numbers copied incorrectly, etc.). It is also possible that there is an error concerning the place of birth: some records list London (census and Drancy list), but others “Conores” (Yad Vashem and Shoah Memorial records), and the Russian nationality. Might it be that the place of birth refers to a district or village near Warsaw?

[11] Victims of Contemporary Conflicts Archives Division of the Ministry of Defense Historical Service, in Caen, ref. 21_P_574_365_23400_DAVCC_copyright_0920

[12] French Official Gazette, March 6, 1919, p. 1046.

[13] See Max/David’s birth certificate, Paris digital archives.

[14] This was stated in the deed drawn up by the notary in 1922.

[15] Anna Rozner was born in Bézano (no doubt Brzezno) in Poland on February 6, 1901. Parents were Joseph Rozner and Dora Maltenfort, both of whom worked in sales, were living in Bézano and obviously still alive in 1934.

[16] After the war, went on to have a second child, Jean, born on October 23, 1948 in Fontenay-aux-Roses.

[17] Decree granting French citizenship by naturalization dated June 2, 1939, n° 29.387 X 37.

[18] This is what he stated on the “non-returned person” file he compiled in 1961, in the paragraph where he was asked to describe the circumstances of his mother’s arrest.

[19] The family was most likely captured during the Velodrome d’Hiver roundup. This is borne out by various dates and departure points for deportation: David (34) was deported from Pithiviers on Convoy 15 on August 5, 1942, Anna (41) from Beaune-la Rolande on Convoy 16 on August 7, 1942, and Simone (7) from Drancy on Convoy 22 on August 21, 1942.

[20] Further research is needed to find out if Max also filed a claim for the disappearance of his brother David Ilzicer.

[21] Our attempts to find out more about him came to nothing, as he is not listed in any of the prisoner databases.

[22] The date was subsequently corrected by a decree dated December 11, 2011: “Ilzicer, née Nados (Eugénie) born January 26, 1878 in Dwinsk (Russia), died on August 5, 1944 in Auschwitz (Poland), not on July 31, 1944 in Drancy (Seine department).”

[23] Both the father and his son drowned while swimming in the Dordogne river at Carlux on August 17, 1981, as reported in Le Nouvelliste et feuille d’avis du Valais, on August 18, 1981.

Français

Français Polski

Polski