Esther SAYAG (épouse FABRE jusqu’en 1946)

Our research into Esther’s life began with this message:

“Dear Teacher

We know next to nothing about Esther Fabre, as you will see from this one record. However, this person survived, as did my mother, Régine Skorka Jacubert, whose biography you can read on our website. Their parallel journeys may be of help to you. We also recommend that you contact the Shoah Memorial in Paris.

I shall be happy to hear from you and remain at your disposal for any further information,

Serge Jacubert”

After a year of research, we have been able to retrace the story of Esther Sayag. We hope you will find our biography interesting.

*******************************************************************************************************

Childhood in Oran

Esther’s story began in the beautiful city of Oran, one day in September 1906.

First of all, let’s set the scene.

In the northwest of Algeria, the clear waters of the Mediterranean Sea crash with a thud against the hulls of boats moored in the port. Going up into the winding lanes, the damp smell of the sea mingles with the sweet scents of the food that the women are preparing and the subtle aromas that drift out of the open windows with their brightly colored shutters. Children play, chasing each other, running around like currents of air among the buildings of the old city.

At the corner of a street, one might run into a street vendor, his hands fixed, as if glued to the handles of his cart, on top of which, in colorful letters, is written the word يانصيب (Lottery), a multicolored sign made to catch the eye of passers-by.

In one of Oran’s numerous squares, he spends a few hours selling tickets before going on his way. The wheels of the carts and wagons and the iron of the horseshoes all clatter on the paving stones in warm tones and traditional patterns. A few grains of sand slip into the joints between the tiles, having blown in from the nearby beach with its line of elegant palm trees. The streets are filled with the sound of chatter and lively conversation.

It was there, between the rue de Ratisbonne and the rue de Fleurus, in the neighborhood surrounding the synagogue, that Esther Sayag was born on September 3, 1906.

Esther was the fifth of six children born to Yamine Sayag and Fortunée Bentilola. When she was born, her parents were in their thirties and already had four children, two girls and two boys. The youngest child, Alia, came along two years after Esther.

Yamine Sayag was a successful grocer and fruit and vegetable merchant. The four girls and two boys were a full-time job for their mother, who stayed home to take care of her family. Esther’s parents were married by a rabbi, which explains why they are listed as single on her birth certificate.

Growing up in France

Yamine Sayag died shortly after Alia was born. Their mother, Fortunée, had no choice but to emigrate to France with the children. She set up home in Marseille, where her father, an auctioneer and civil servant, was living. Uprooting the family like that was not easy.

Since the family had no income, they were dependent on their grandfather and the children were still young. On top of this, they had to deal with the repercussions of the First World War which, fortunately, did not affect Marseille too much.

The 1920s were a happier time. The family moved to Paris and the girls got married one after the other. Esther got married on October 29, 1927, just a few days after she came of age.

The war years

When France went to war in 1939, Esther and her husband Jean-Baptiste Fabre were not overly concerned. And when Philippe Pétain was appointed President of the Council ( the equivalent of Prime Minister) on May 16, 1940, many French people were happy to see the appointment of a First World War hero who stood a good chance of helping France win.

On June 17, the government called for an armistice and on July 10, the majority of the deputies gathered in Vichy and granted total power to Pétain. France was occupied by the Nazis. Philippe Pétain installed an authoritarian regime and began to collaborate with Hitler’s Germany on July 30, 1940.

On October 7, 1940, the French state, Pétain’s new regime, repealed the Crémieux decree. France had conquered Algeria in 1830 and remained in power until 1870. From 1870 onwards, the Crémieux decree (named after Adolphe Crémieux) created a new status for the “indigenous Jews” of Algeria, of which there were around 35,000, including Esther’s family. In order to benefit from it, they had to agree to give up the religious practices associated with Judaism. Their living conditions improved somewhat and their status was a little more secure, but it was still inferior to that of French citizens in mainland France.

When Pétain decided to repeal this law, the Jewish and Muslim people of Algeria found themselves stateless. Esther’s family began to worry. But this was only the beginning. In October 1940 a decree relating to “the status of the Jews” was issued: they had to take part in a census, which meant that they were put on a list.

In 1941, step by step, Jews were no longer allowed to be doctors or politicians or to be teachers or even students in schools. Their identity cards were stamped with the words “Jew”.

Then, at the end of 1941, Jews and stateless foreigners who had arrived in France after 1936 began to be interned. In the South, many foreigners were locked up in the Les Milles camp, which our class was able to visit. In the Paris area, an internment camp was set up in Drancy. We shall come back to this later.

For Esther’s family, the situation took a dramatic turn. Her brother-in-law, Robert Mercante, who was the husband of Rachel, one of Esther’s two older sisters, was arrested, locked up in Drancy and deported to Auschwitz on Convoy No. 3 on June 22, 1942. He was murdered on July 24 of the same year.

After that, Esther helped the other members of her family to go into hiding. A short time later, she herself moved to Marseille. It was her niece, Danielle, who told us about this.

Three of Esther’s cousins, Roger, Edith and Renee, who were much younger than her, were sent to Burgundy and kept hidden throughout the war.

In July 1942, the French police carried out a roundup in the 10th district of Paris and a large number of foreign Jews were arrested and then deported to concentration camps. Gidalia and Simha Zavarro, Esther’s aunt and uncle, asked Mr. Baccary, the teacher at their children’s elementary school, to take them in to keep them out of harm’s way. Realizing that the situation was getting worse, Mr. Baccary moved the children to his vacation home where his wife and daughter took care of them. André Baccary forged their identity documents and enrolled the children in the village school, thus keeping them safe. This act of bravery and compassion led the Baccary family being recognized as “Righteous Among the Nations”. This is a distinction that is awarded to people who saved Jewish people’s lives during the Holocaust.

In November 1942, the Nazis occupied the entire country, but Esther managed to escape the roundups and stayed on in Marseille, where she worked as a milliner.

She came close to death more than once. In the early summer of 1944, as the Allied forces were advancing, thousands of Jews were transported to Drancy from cities in the south of France, including Marseille, where Esther was living in hiding, and were then deported. Esther was eventually caught, however, during a round-up in the summer of 1944, and was transferred to Drancy camp on July 24.

Internment in Drancy camp

The building complex at Drancy, about 20 miles north of Paris, was originally designed to provide low-cost housing for disadvantaged people.

The building complex at Drancy, about 20 miles north of Paris, was originally designed to provide low-cost housing for disadvantaged people.

In July 1940, the Wehrmacht commandeered the site.

The complex was first used as a temporary detention camp for French and English prisoners of war. In 1941, while the building was still unfinished, it was converted into an internment camp for foreign Jews, and then for French Jews as well. It has to be said that the building was ideally suited to this purpose: built on 4 floors around a courtyard about 200 yards long and 40 yards wide, it was surrounded by 2 rows of barbed wire and a sentry walk, and watchtowers were added at each corner.

For 3 years it remained the main internment site for Jews before they were deported from Le Bourget railroad station (from 1942 to 1943) and then from Bobigny station (from 1943 to 1944) to the Nazi extermination camps, mainly Auschwitz.

In 1942, as the number of round-ups increased, mass arrests took place, in particular in Paris. The camp held up to 800,000 prisoners until they were transferred to the German concentration camps.

The living conditions were very harsh, the sanitary conditions were appalling and the people were hungry. The Germans circulated propaganda photos of the Drancy camp. They showed the internees looking happy to be there.

Convoy no. 77, with Esther on board, left Bobigny on July 31, 1944. It was the last convoy to deport Jews from Drancy internment camp.

Deportation to Auschwitz and then to Kratzau

On July 31, 1944, the internees were gathered in the courtyard at Drancy and told that they were about to be taken elsewhere.

Esther stood facing the long line of cattle cars that made up Convoy 77, then she stepped forward and looked back one last time as she climbed aboard the train. She saw children who had been separated from their parents and men and women hugging each other as they were loaded into different cars. With her, there were about sixty women and children all squashed into one cramped cattle car with only a rusty metal bucket to urinate in. With no food or water, everyone was aware that some people were likely to die before they got to Auschwitz. Esther could barely feel anything at all: she was afraid that she was about to die, never to see her family and friends again. She had known the risk she was running when she decided to help them, and she had put her own life in danger to save them. Other women were forcibly dragged and shoved into the wagon. None of them tried to sit down but in any case, there wasn’t enough room. The doors were closed behind the last few people to get in, and a few minutes later the convoy set off. Esther waited, still standing. The train was on its way to Auschwitz.

After a two or three day journey (the hours all merged together and everyone lost track of time) the train stopped.

The women were dragged out of the car, lined up, inspected and sorted like objects. Esther watched the older women leave. She did not know at the time that they were about to be killed, but she guessed that their fate was already sealed.

The women were dragged out of the car, lined up, inspected and sorted like objects. Esther watched the older women leave. She did not know at the time that they were about to be killed, but she guessed that their fate was already sealed.

Esther was taken to a room, along with some other young women. They were told to undress, right there in front of everyone, and to go into a communal shower, where grayish water descended on them and drenched them to the core.

After the shower, the women were tattooed on their forearms. Esther watched, grimacing with pain, as the numbers 2, 5, 6, 6, 1 appeared. She was then shoved towards a big pile of clothes and the guards yelled at her to get dressed!

She was placed in a barrack hut known as a block. The beds were made of planks of wood, with no mattresses, pillows or sheets. The stifling July heat seeped in through the thin walls and she later discovered that the cold crept in likewise in winter.

When we looked at her repatriation card, we discovered that she was later transferred to Kratzau.

We learned from the biographies of other deportees that there were armaments factories in Kratzau where the deportees worked. Some of them said that being in a permanent building was almost a luxury. Others described how they hoped that the camp would be bombed, because that would put an end to their misery and slow down the Nazis’ progress. In Kratzau, Esther certainly worked hard. She lost a lot of weight and almost died several times, and as a result she aged prematurely.

Esther never really confided in anyone at all about what she experienced in Auschwitz.

Danielle, her niece, remembers only that her aunt was terrified of trains. Her aunt also told her sisters that in the camps, the deportees would fight over a little piece of bread, even between mother and daughter. It was a painful time and it was very hard even to survive.

Esther’s return to France

When Esther came back from the camps, she had a bad cough, was very weak and had lung problems.

She was very thin and remained so all her life. Since she was unable to work, she lived on benefit and went to live with her sister Jeanne.

Her marriage did not survive the traumatic impact of the camps. She and her husband got divorced in 1946.

She spent the rest of her life in Paris, living with her older sister Jeanne, supported by her family and with her cat – well, the cat that her niece Danielle had given her: Charles-Auguste.

Esther died on January 26, 1983.

***********************************************************************************************

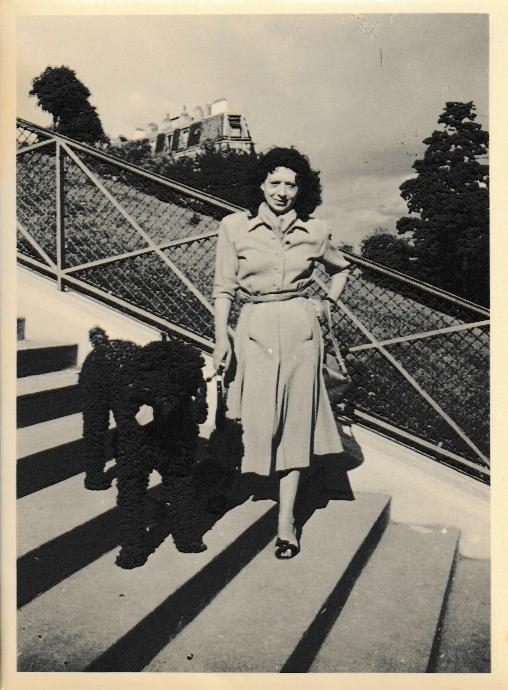

In the course of our research, we tracked down Danielle, Esther’s niece, who was very happy to hear that we were investigating her aunt’s life story. She shared some memories and photographs with us, which are included in this biography.

We also managed to piece together the Sayag family tree.

***********************************************************************************************

Students’ observations

Hélin:

“We are 9th graders at the Emile Thomas school and we are involved in a club called “Convoy 77” in which we learn a lot about this important period. Through the club program, we are increasing our knowledge about the Holocaust. This club is really fascinating because it has allowed us to gain valuable insights, to conduct research and to make contact with the family of a deportee. We are inquisitive and enthusiastic, which is why this project was perfect for us. We are highly motivated and committed and we have done our utmost to tell Esther’s story.”

Juliette

“I jumped at the chance as soon as I heard about this club. Searching for family trees, old records (birth certificates, marriage certificates, etc.) or finding telephone numbers reminds me of my favorite game: “Cluedo”. I love to immerse myself in this kind of investigation, which revives the history of our country. It also enhances our cultural awareness. I have always been fascinated by history and as a child I dreamed of becoming an archaeologist. This project also appeals to me because it honors the memory of those who have gone before.”

Tayana

“I was very interested in this club because when I learned about the project, I thought it was a great idea to explore such an interesting and important event by playing the role of “Sherlock Holmes”. It’s very innovative, and on top of that, researching the life of a deportee enables us to learn more about the history of Jews in France; their place in society at the time and the suffering they endured during World War II.

Marine

“I read on a poster that there was a “Convoy 77” club for 9th graders. I was intrigued, so I went to see what it was all about. I loved the first session and found it very informative. I’m very curious by nature and I really like the idea of researching things ourselves. Finding out about a deportee’s life and reconstructing it is amazing. You challenge yourself to find out a little more each time. This club is an opportunity to really educate myself and learn more about the deportation. We feel like detectives and our workplace is the internet and the library. I love that we keep a logbook where we can keep track of all our exploration and discoveries. I hope that Esther Fabre’s family will appreciate our work.”

Claire

“I was interested in this project first and foremost because it provides an opportunity to learn more specific topics than in a regular history class. Secondly, tracing the life of a deportee is a really interesting experience that we can’t do in class due to time constraints. The fact that club meetings are held during the lunch break is a plus: instead of doing nothing, we can take advantage of this time to grow and to learn.”

Téhani

“My friend Jade and I joined this club because we have been interested in World War II for some time. We are interested in the Third Reich and how its ideology destroyed entire populations. Deportation was a key aspect of the “Final Solution” policy. The club is informative and teaches us how to research and find information. Currently, we are working on a piece about the atmosphere in Oran, where Esther Fabre spent her childhood, in the early 20th century.”

*******************************************************************************************************

Sources:

- Source : ANOM – Archives d’Outre-Mer

- Source : Archives de la ville de Paris

- Source : AJPN – Affichage dans les Bouches-du-Rhône

- Source : Mémorial de la Shoah – MERCANTE Robert

- Source : Yad Vashem France

- Source : Herodote.net + Wikipedia France

- Source : Association Convoi 77

Links:

- http://anom.archivesnationales.culture.gouv.fr/caomec2/osd.php?territoire=ALGERIE®istre=37829 page 598

- http://tinyurl.com/52s3vw7y page 10

- http://www.ajpn.org//images-comms/1341420236_Recensement-israelites-a-Marseille.jpg

- https://ressources.memorialdorg/zoom.php?code=177242&q=id:p_255249&marginMin=0&marginMax=0&curPage=0

- https://yadvashem-france.org/dossier/nom/11253/

- https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/a/a8/Bundesarchiv_Bild_183-B10919%2C_Frankreich%2C_Internierungslager_Drancy.jpg

+ https://www.herodote.net/16_juillet_1942-evenement-19420716.php

Image Sources :

1 – http://benzaken-descendance.centerblog.net/68-oran-ville-fran-aise-1831-1930

2 – https://www.geneanet.org/cartes-postales/view/217096#0

3 – http://simon.sirour.free.fr/page29/page29.html

4 – http://simon.sirour.free.fr/page2/page2.html

5 – Personnel – Danielle Azerraf

6 – Personnel – Danielle Azerraf

7 – http://www.ajpn.org//images-comms/1341420236_Recensement-israelites-a-Marseille.jpg

8 – https://ressources.memorialdelashoah.org/zoom.php?code=177242&q=id:p_255249&marginMin=0&marginMax=0&curPage=0

9 – https://www.tripadvisor.se/LocationPhotoDirectLink-g1080240-i180742853-Drancy_Seine_Saint_Denis_Ile_de_France.html

10 – https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/a/a8/Bundesarchiv_Bild_183-B10919%2C_Frankreich%2C_Internierungslager_Drancy.jpg

11 – https://www.herodote.net/16_juillet_1942-evenement-19420716.php

12 – https://www.gregoiredetours.fr/xxe-siecle/seconde-guerre-mondiale/annette-wieviorka-et-michel-lafitte-a-l-interieur-du-camp-drancy/

13 – https://www.nbcnews.com/news/world/bookkeeper-auschwitz-oskar-groening-set-stand-trial-n344796

14 – Association Convoi 77

15 – Personnel – Danielle Azerraf

16 – Personnel – Danielle Azerraf

17 – Arbre généalogique réalisé par les élèves.

إستير صياغ (زوجة فابر إلى سنة 1946)

1906-1983/ الولادة : وهران / الاعتقال : مارسيليا / الإقامة : مارسيليا، وهران، الجزائر

هذه السيرة التي أنجزناها عن حياة إستير بدأت بهذه الرسالة :

“الأستاذة العزيزة، لا نعرف تقريبا أي شيء عن إستير فابر، مثلما سترون في هذه الوثيقة الوحيدة. لكن هذه السيدة عاشت، مثل والدتي، ريجينا سكوركا جاكوبير، والتي يمكن لك قراءة سيرتها في هذا الموقع. فمساراهما المتوازيان يمكن أن يساعداننا. كما ندعوك أيضا للاطلاع على ميموريال المحرقة. وسأظل في انتظار ردك ورهن إشارتك.

“الأستاذة العزيزة، لا نعرف تقريبا أي شيء عن إستير فابر، مثلما سترون في هذه الوثيقة الوحيدة. لكن هذه السيدة عاشت، مثل والدتي، ريجينا سكوركا جاكوبير، والتي يمكن لك قراءة سيرتها في هذا الموقع. فمساراهما المتوازيان يمكن أن يساعداننا. كما ندعوك أيضا للاطلاع على ميموريال المحرقة. وسأظل في انتظار ردك ورهن إشارتك.

سيرج جاكوبير.”

بعد سنة من البحث والعمل، تمكّنا من تتبع حياة إستير صياغ ونتمنى لكم قراءة طيبة.

*******************************************************************************************************

طفولة في وهران

حكاية إستير تبدأ في المدينة الجميلة وهران، ذات يوم من شتنبر 1906.

وفيما يلي الحكاية.

في شمال غرب الجزائر، الماء الشفاف للبحر الأبيض المتوسط يأتي ليتكسر في صوت خافت على هياكل السفن الراسية بالميناء. صعودا على طول الأزقة المتشعبة. انبعاثات الرطوبة البحرية تختلط بالروائح الرقيقة للمأكولات المعدّة من قبل النساء، أدخنة طيبة تتطاير من النوافذ نصف المفتوحة والمزيّنة بشبابيك ذات ألوان مشعّة. أطفال يلعبون ويجري بعضهم وراء بعض، مثل تيارات هوائية، بين منازل المدن العتيقة.

في مدار الزقاق، يمكن أن نقع وجها لوجه مع بائع متجول، يداه مسمّرتان كما لو كانتا لاصقتين بمقبضيْ عربته والتي كتبتْ فوقها بحروف ملونة، كلمة “يانصيب” علامة متعددة الألوان صُنعت لتجذب نظر المارّة. وحين تكون في إحدى الساحات العديدة بوهران، تبقى هناك بعض الساعات كي تبيع أوراق اليانصيب قبل مواصلة السير. عجلات العربات المجرورة وصفائح أحذية الخشب، كل ذلك يحدث صوتا فوق الأرضيات ذات الرسوم التقليدية. بعض حبات الرمل تتسرّب بين فتحات مربعات الزليج بعدما تطايرت من الشاطئ جد القريب الذي تحدّه نخلات باسقة. وفي الأزقة تسمع عدة محادثات.

هناك، بين زنقة راتيسبون وزنقة فلوروس، في الحي المحيط بالكنيس، وُلدت إستير صياغ في ثالث شتنبر 1906.

إستير هي الخامسة بين ستة أطفال ليامين صياغ وفورتوني بنطوليلا. حينما وُلدت كان أبواها في الثلاثينيات ولهما أربعة أطفال آنذاك : بنتان وولدان. سنتان بعد ولادة إستير ،جاءت الصغيرة الأخيرة عالية ليكبر عدد الإخوة.

يامين صياغ هو تاجر خُضر وبقّال مستقر. البنات الأربع والولدان يشغلان كل وقت والدتهم التي تتكفّل بعائلتها. تزوج والدا إستير أمام الحاخام وهو ما يُفسر أنهما سُجلا عازبين في عقد ولادتها.

فترة شباب فرنسي

توفي يامين صياغ بوقت قليل على ولادة عالية. فلم يكن للأم فورتوني من خيار : هاجرت مع أطفالها إلى فرنسا واستقرت بمارسيليا حيث كان يعيش أبوها الدلاّل والموظف. كان هذا الاقتلاع من الجذور صعبا عليها.

لا تتوفر للعائلة وسائل عيش. فقد كانوا يعيشون على نفقة الجد والأطفال صغار. يُضاف إلى ذلك أصداء الحرب العالمية الأولى والتي، لحسن الحظ، لم تصب مارسيليا إلا قليلا.

سنوات 1920 كانت أكثر سعادة. رحلت العائلة إلى باريس حيث تزوجت البنات الواحدة تلو الأخرى. تزوّجت إستير في 29 أكتوبر 1927 أياما قليلة على بلوغها.

الحياة إبان الحرب

حين دخلت فرنسا الحرب عام 1939، لم تكن إستير وزوجها جان باتيست فابر قلقيْن بشكل خاص. فحين عُين فيليب بيتان رئيسا للمجلس (ما يعادل الوزير الأول) في 16 ماي 1940، كان كثير من الفرنسيين سعداء وهم يرون عودة بطل الحرب العالمية الأولى والذي كانت له جميع الحظوظ ليجعل فرنسا تنتصر.

وفي يوم 17 يونيو تمّ طلب الهدنة، وفي عاشر يوليوز، منح غالبية النواب المجتمعين في فيشي كامل الصلاحيات لبيتان. احتلّت فرنسا من طرف ألمانيا النازية. وضع فيليب بيتان نظاما سلطويا ونهج أسلوب التعاون منذ 30 يوليوز 1940 مع ألمانيا الهتلرية.

أُلغي مرسوم كريميو يوم سابع أكتوبر 1940 بقانون للدولة الفرنسية، هو النظام الجديد لبيتان. فرنسا كانت قد احتلت الجزائر بين 1830 و1870. وابتداء من 1870 فإن مرسوم كريميو (من اسم أدولف كريميو) منح وضعية جديدة لليهود المحليين بالجزائر، حوالي 35.000 يهودي (ومن بينهم عائلة إستير). وللاستفادة من هذه الوضعية كان عليهم التخلي عن قواعد الحياة الدينية المرتبطة باليهودية. تحسّنت ظروف حياتهم بعض الشيء وتحسّن نظامهم قليلا. لكنه ظلّ دون مستوى ما كان مطبقا على فرنسيي الميتروبول.

وحين قرّر بيتان إلغاء هذا القانون، أصبح جميع الأشخاص اليهود والمسلمين في الجزائر بلا وطن. بدأت عائلة إستير تقلق. ولكن كانت تلك البداية. ففي أكتوبر 1940 نُشر القانون الخاص باليهود، وتم إحصاء المعنيين وتقييدهم في لوائح.

وفي 1941، شيئا فشيئا لم يعد الحق لليهود في أن يكونوا أطباء أو سياسيين أو حتى الذهاب إلى المدرسة لو كانوا أساتذة أو تلاميذ. ووضع على بطائق الهوية طابع يحمل كلمة “يهودي” أو “يهودية”.

وفي نهاية 1941، تمّ سجن جميع اليهود أو الأجانب بلا وطن الذين دخلوا فرنسا بعد 1936.

وفي الجنوب سُجن كثير من الأجانب في معسكر “دي ميل” الذي قُمنا بزيارته مع قسمنا. كما سينشأ في جهة باريس معسكر اعتقال بدرانسي سنتكلم عليه فيما بعد.

بالنسبة لعائلة إستير أصبحت وضعيتها درامية. ألقي القبض على روبير مركانت زوج إحدى أخواتها الكبيرات راشيل وسُجن بدرانسي ثم رُحل إلى أوشفيتز عبر القافلة في ثالث يونيو 1942 . 1942 حيث ستتم تصفيته يوم 24 يوليوز من نفس السنة..

ومنذ ذاك ستُساعد إستير أفراد عائلتها على الاختباء. وبعد فترة سترحل هي بدورها إلى مارسيليا.

ابنة شقيقتها دانيال، هي من حكت لنا القصة.

أما رُوجي، وإديث وروني وهما، تباعا، ابن وبنت خال إستير ، وأصغر منها سنا. فقد أرسلوا إلى بوركون لإخفائهم طوال فترة الحرب.

وفي يوليوز 1942، قامت الشرطة الفرنسية بحملة توقيفات في الدائرة العاشرة حيث اعتقلت عددا كبيرا من اليهود الأجانب ورُحلوا نحو معسكرات الاحتجاز.

طلبت جيداليا وسميحة زافارو، وخال وخالة إستير من السيد باكاري، معلم أطفالهم في المدرسة الابتدائية أن يتكفّل بهم ويضعهم في مكان آمن. لاحظ السيد باكاري أن الوضعية تتفاقم فوضع الأطفال في المنزل الذي يشغله إبان العطل وتكلفت بهم زوجته وابنته. ثم أنجز لهم أندريه باكاري أوراقا مزوّة وسجّلهم بمدرسة القرية وهو ما حماهم. هذا العمل الشجاع والتضامني جعل عائلة باكاري تحصل على صفة “عادل بين الأمم” وهو لقب يُمنح للأشخاص الذين أنقذوا يهودا من المحرقة.

في نونبر 1942، قرر النازيون احتلال كل الإقليم ولكن إستير نجحت في الإفلات من الحملات وبقيت في مارسيليا حيث كانت تشتغل صانعة قبعات.

وقد نجت إستير من الموت أكثر من مرة. وفعلا، ففي بداية صيف 1944، أمام تقدم قوات الحلفاء، وُجه آلاف اليهود من مدن الجنوب إلى درانسي، ومن بينها مارسيليا حيث تختبئ إستير، لكي يرحّلوا. لكن سينتهى الأمر باعتقالها خلال غارة للشرطة في صيف 1944 ونُقلت إلى معسكر درانسي يوم 24 يوليوز 1944.

السجن في معسكر درانسي

في الأصل، صُممت هذه المجموعة من العمارات الموجودة على بعد 30 كلم تقريبا من باريس من أجل إسكان فئات هشة وبثمن زهيد.

في الأصل، صُممت هذه المجموعة من العمارات الموجودة على بعد 30 كلم تقريبا من باريس من أجل إسكان فئات هشة وبثمن زهيد.

في يوليوز 1940، تسلّم الجيش الألماني هذا المكان الذي يُستعمل كمعسكر مؤقت لأسرى الحرب الفرنسيين والإنجليز. وفي 1941، والبناية لم يكتمل بناؤها بعد، تحوّل المكان إلى معسكر لاحتجاز اليهود الأجانب، ثم اليهود الفرنسيين. وينبغي القول بأن البناية تتلاءم بسهولة : فهي مبنية على أربع طبقات حول ساحة من 200 متر تقريبا طولا على 40 متر عرضا، ومُحاطة بصفين من الأسلاك الشائكة وطريق دائري، بينما يوجد برج المراقبة في الزاوية.

وخلال ثلاث سنوات، اعتبر المكان الرئيسي للاحتجاز قبل ترحيل اليهود من محطة البورجي (من 1942 إلى 1943)، ثم من محطة بوبيني (من 1943 إلى 1944) نحو معسكرات التصفية النازية وخاصة نحو أوشفيتز.

وفي 1942، بينما تضاعفت غارات الشرطة، أصبحت الاعتقالات جماعية وبالخصوص في باريس.

يضم المعسكر حتى 800 ألف معتقل عابر، أي قبل نقلهم نحو معسكرات الترحيل الألمانية.

كانت ظروف الحياة جد صعبة، ووضعية النظافة كارثية، والجوع كان دائما. وُزعت صور للدعاية لمعسكر درانسي تظهر معتقلين سعداء.

أما القافلة 77، التي كانت ضمنها إستير يوم 31 يوليوز 1944 فكانت آخر قافلة لترحيل اليهود من معسكر الاحتجاز بدرانسي.

الترحيل إلى أوشفيتز – كراتزو

يوم 31 يوليوز 1944، تجمّع اليهود في الساحة وتمّ إخبارهم بأنهم سيذهبون إلى مكان آخر.

أمام صف عربات القافلة 77، تقدمت إستير وقبل أن تصعد بدورها إلى القطار، التفتت إلى الوراء لآخر مرة. رأت أطفالا انتزعوا من آبائهم، ونساء ورجالا تعانقوا قبل الصعود إلى مختلف العربات. كان هناك مع إستير حوالي ستين امرأة وطفلا مكدّسين في عربة للبهائم ضيقة وبها سطل واحد صدئ للتبول. بدون أكل ولا ماء، يعرف الجميع بأن بعض الأشخاص قد يموتون قبل الوصول إلى أوشفيتز. لم تعد إستير ترى شيئا، كانت تخاف أن يأتيها الموت في تلك اللحظة دون الالتقاء بعائلتها وأصدقائها. كانت تعرف مغبة ما سيصيبها لو ساعدتهم، ومع ذلك فضلت المخاطرة لتقديم المساعدة لهم. نساء أخريات حُملن بقوة وكُدسن في العنبر. لا واحدة منهن فكرت في الجلوس. وكيفما كان الحال فليست هناك أماكن كافية. أُغلقت أبواب العربات وراء آخر الوافدات وبعد دقائق، تحركت القافلة. إستير تنتظر واقفة، وغادر القطار نحو أوشفيتز.

بعد يومين أو ثلاثة من السفر (فالساعات اختلطت، ولا أحد أصبح يدرك مفهوم الوقت) توقف القطار.

جرت النساء خارج العربة ووقفن في الصف، حيث خضعن للفحص والانتقاء كأنما كنّ مجرد أشياء. رأت إستير كيف أن كبيرات السن قد ذهبن. لم تكن تعرف حينها بأنه ستتم تصفيتهن، ولكنها خمنت بأن مصيرهن قد تقرّر.

تم اقتياد إستير مع نساء شابات أخريات إلى غرفة. طُلب منهن إزالة ملابسهن، هناك أمام الملأ، وتمّ الولوج إلى حمام جماعي. نزل عليهن ماء داكن بلّلهن حتى العظام.

بعد الحمام، تم وشْم النساء في الساعد. رأت إستير وهي تتألم تكوين الأرقام على جسدها 25661. دفعت بعد ذلك بعنف أمام كومة كبيرة من الملابس وصرخ فيها بأن تلبس. !

وجدت نفسها في ما يسمى البلوك : الأسرة عبارة عن ألواح خشبية، بلا غطاء للسرير، ولا فراش. الحرارة الخانقة تمر عبر الجدران لأن الشهر كان يوليوز واكتشفت أن البرد كذلك يتسرب بنفس الطريقة في فصل الشتاء.

وبالاطلاع على بطاقة العودة، لاحظنا بأنها نُقلت إلى كراتزو.

وقد علمنا بعد قراءة سير مرحّلين آخرين أنه كانت توجد في كراتزو معامل أسلحة كان يشغّل فيها المرحّلون. تحكي بعض النساء بأن وجودهن في بناية صلبة كان بمثابة ترف.

وصرحت أخريات بأنهن كنّ يأملن أن يُقنبل المعسكر حتى تنتهي مآسيهن، ويُسبب ذلك في أضرار هامة تُعرقل تقدم النازيين.

اشتغلت إستير كثيرا في كراتزو. ضعفت جسديا وكادت أن تموت عدة مرات، وهو ما جعلها تشيخ قبل الأوان.

لم تبُح إستير لأي أحد بتجربتها في أوشفيتز. تتذكر دانيال ابنة خالتها بأنها كانت مرعوبة من القطارات. خالتها باحتْ أيضا لأخواتها بأنه في المعسكرات، كان المرحّلون يتعاركون، حتى بين أم وابنتها، من أجل قطعة خبز صغيرة. كان ذلك يخلق المعاناة، وكان من الصعب جدا البقاء على قيد الحياة.

العودة إلى فرنسا

بعد العودة من المعسكرات كانت إستير تسعل، أصبحت هشة وكانت تعاني من مشاكل في الرئة.

بعد العودة من المعسكرات كانت إستير تسعل، أصبحت هشة وكانت تعاني من مشاكل في الرئة.

أصبحتْ جد هزيلة وظلت هكذا طوال حياتها. فلم تعد قادرة على العمل، وعاشت بفضل منحة إلى جانب أختها جان.

لم يصمد زواجها لتجربة المعسكرات الصادمة. وتمّ الطلاق سنة 1946. أمضت بقية أيامها في باريس، بالقرب من أختها الكبرى جان، محاطة بعناية عائلتها وقطها – يعني القط الذي جلبته لها دانيال ابنة شقيقتها : شارل-أوغست. وتوفيت إستير يوم 26 يناير 1983.

*******************************************************************************************************

خلال إعدادنا لهذه السيرة، استطعنا العثور على أثر دانيال، ابنة شقيقة إستير والتي سعدتْ حين علمتْ بأننا كنا نقوم بأبحاث حول خالتها. وهي من أمدّتنا بذكريات وصور أدرجناها في هذه السيرة، كما استطعنا تركيب شجرة الأنساب لعائلة صياغ.

Français

Français Polski

Polski