Germaine WAGENSBERG

The biography you are about to read was written by Sidonie Berthelot, Zoé Boivin, Amalia Cervantes, Elly Dana, Camille Froment, Jade Gautier, Louise Legouis, Antonin Louis, Siloé Pascarel and Maxime Wamo, a group of 9th grade students from the La Cerisaie middle school in Charenton during the 2022-2023 school year, supervised by their history and geography teachers, Nathalie Baron and Sonia Drapier.

As luck would have it, our research on the Internet led us to Gilles Hejblum, Germaine’s son. We would like to thank him for all the help he has given us throughout our investigation by providing us with a large number of useful records and also the contact details of his aunt, Madeleine Germain, to whom we would also like to express our gratitude.

Both of them came to speak at our school.

You can watch Madeleine’s testimony in French, filmed by the Créteil Departmental Archives service, here: Madeleine Germain.

I – 1921-1938: Before the war

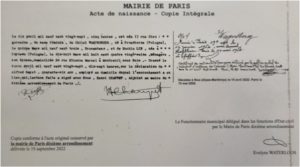

According to their daughter Germaine’s birth certificate, Chilel Wagensberg was born on March 15, 1903 in Przedbórz (near Łódź), while his wife, Ruchla Lin, was born on March 18, 1896 in Czyżewo (near Warsaw).

Chilel and Ruchla met in France, although we do not know how. They probably both fled their homeland as a result of anti-Semitism: there were widespread pogroms in Poland at that time.

Germaine’s birth certificate – 1927 – Source: Paris Civil Register

Chilel arrived in the Paris area around 1921-1922. He came from a family of 18 children, including “two sets of twins”. He left alone, having refused to follow in his father’s footsteps and become a rabbi.

Chilel and Ruchla met in Paris in 1925, perhaps at a July 14th ball. They were married in 1926, and a year later, on April 10, 1927, Germaine was born in the 10th district of Paris. Why Ruchla gave birth to her first daughter in Paris when the couple lived on the outskirts, in Montreuil-sous-Bois, remains unclear.

In the years that followed, Jacqueline was born on June 1, 1930 in the 12th district of Paris, and Madeleine on March 13, 1934 in the 20th district. Although the parents never acquired French citizenship themselves, they did apply for French citizenship by naturalization for Germaine and Jacqueline, but not for Madeleine, probably due to administrative difficulties.

Chilel and Ruchla’s wedding photo – 1926

Source: Madeleine Wagensberg Germain

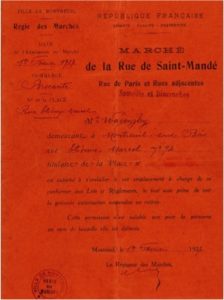

The family set up home at 94 rue Etienne Marcel in Montreuil, in the present-day Seine-Saint-Denis department of France. This address is shown on a receipt from a flea market, the Puces de Montreuil.

Receipt from the Montreuil flea market – February 1, 1927

Source: Gilles Hejblum

According to Jean Laloum’s book “Les juifs dans la banlieue Parisienne” (“Jews in the Paris suburbs”), Montreuil was home to a large Polish Jewish community.

The author describes it as “a fully-fledged community with its own synagogue, its own food scene with Jewish groceries, butchers and bakeries, a well-organized, left-leaning community with numerous non-profit associations”.

Chilel or Ruchla may have had friends in Montreuil who encouraged them to move there.

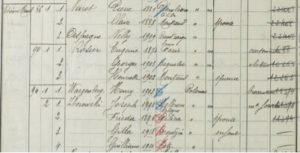

The Wagensberg name only appears at 94 rue Etienne Marcel in Montreuil in the 1926 census. Even then, only the father is listed, with the first name of Henry rather than Chilel. The address is not listed at all in the 1921, 1931 or 1936 censuses. This is still a mystery to us…

Extract from the 1926 census

Source: Seine-Saint-Denis departmental archives

Be that as it may, the girls’ parents worked hard. Their father, Chilel, started out as a road builder, working on the paving of the Rue de Bercy. He then set up as a second-hand dealer, and before long began to specialize in mattresses.

After starting out with a stall on the Montreuil flea market, the couple set up their own store. Business must have been good, since the company owned two automobiles and a horse-drawn carriage, and even employed several workers. According to Germaine and Madeleine, Chilel even invented the folding metal bed and the “suitcase bed”.

Ruchla was a quilter, making mattresses, pillows and cage beds. She had to carry heavy loads, which resulted in a herniated disc and, a few years later, her legs became paralyzed.

The business did well and the family soon made plenty of money.

Life at home was happy, the girls went to state school and Germaine started playing the piano in 1933-34. She had one at home and took private lessons. As for Ruchla, she enjoyed dressing the three girls in pretty clothes and sandals.

Ruchla’s father was a rabbi in Poland. According to Madeleine, he had his beard ripped off on his way back from a wedding ceremony and died of septicemia six weeks later. After Germaine was born in 1928, his wife Chaja moved to France and lived with the Wagensberg family.

Chaja took great care of the girls, and is described by Madeleine as a very kind woman. She spoke only Yiddish and was very religious, going to synagogue and eating only kosher food, unlike the rest of the family.

Chilel was heavily involved in politics. Madeleine told us that he took part in a demonstration in support of Sacco and Vanzetti in Paris on August 7, 1927. This led to the police opening a file on both Chilel and Ruchla, thus undermining their application for French citizenship by naturalization.

Chilel joined the Communist Party, which he believed could help curb the anti-Semitism that was rampant Europe. The couple helped Jewish and Spanish refugees by hiding them in their barn. There were always a lot of people in the house according to Germaine’s testimony.

In 1934, Chilel travelled to the USSR, to Birobidzhan, a Jewish state in its infancy, as part of a Communist delegation, with a plan, abandoned soon afterwards, to move his family there. to the infant Jewish state.

In 1938, Chilel volunteered to join the ranks of the French army.

However, around this time he decided to go off alone, without telling his family, to Cuba, leaving behind his sick wife and three daughters. Throughout the war, the girls never heard from him. Madeleine just told us that he had left in a cab, calling him “not a very nice man”. Ruchla then went to the police station to report that Chilel gone missing.

In August 1939, when war was declared, the Wagensberg family’s daily routine was changed forever.

II – 1939-1944: Life in war-torn France

Right from the start of the war, in September 1939, the decision was taken to evacuate children living in Paris. Special trains were allocated to transport Parisian children to other departments of France. Germaine, Jacqueline and Madeleine were separated from their mother and grandmother, and taken to Burgundy along with the other children in their school.

The girls were sent to a village in Burgundy. They were then separated for a time, with Jacqueline in Sens and Madeleine in Joigny.

During the winter of 1940, Ruchla and Chaja found lodgings in Bassou, the “snail capital” of the Yonne department, where the Countess took in refugees in her château. The five of them then stayed in a house opposite the church, and Germaine and Jacqueline went to the village school.

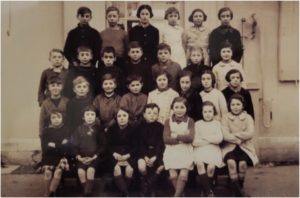

Bassou school photo (Yonne department) – March 1940

Bassou school photo (Yonne department) – March 1940

Source: Madeleine Wagensberg Germain

Germaine on the second row from the top, on the left – Jacqueline in the first row, on the right

Ruchla then decided to return to the Paris area. In 1941, as part of the Aryanization program, Jewish people had all their property, businesses and bank accounts seized. As a result, the store in Montreuil was taken over and its accounts were audited by the receivers. Ruchla managed to keep the house and outbuildings, but had to sell everything else, including the automobiles. She was left with no income.

The situation became even more complicated when Ruchla, suffering from a slipped disc, was hospitalized at the Pitié-Salpêtrière Hospital. She was admitted in the name of Walin (a combination of Wagensberg and Lin). Germaine thus found herself in charge of the family when she was only 13. As of 1941, she had to find work and therefore joined the social security system.

She first worked in a Mazda factory, filling batteries, before taking on a series of odd jobs: selling newspapers, then pretzels, and doing housework etc.

In October 1942, her grandmother Chaja became difficult to cope with and was placed in the Rothschild Institute with the help of a social worker.

Since 1941, the Rothschild hospital has been the only one where Jewish doctors were still allowed to practice. It catered only for Jewish patients, who were no longer admitted to any of the other hospitals in Paris.

The Social Services Department then placed the three girls in the “Hospice for assisted children in the Seine department” on avenue Denfert-Rochereau. Soon afterwards, however, Marshal Pétain issued a decree that banned Jewish children from the welfare system. The girls then found refuge with the UGIF, The Union générale des Israélites de France or General Union of French Jews. The UGIF was an organization that had been founded according to a law dated November 29, 1941, for the purpose of representing Jews in their dealings with the authorities and providing them with support. All Jews living in France were required to join the UGIF, since all the other Jewish organizations had been closed down and their assets donated to the UGIF.

The sisters were initially placed in the UGIF children’s home on rue Lamarck in the 18th district of Paris. This coincided with the period when the Vichy government introduced the yellow star, and when the French authorities began to send children to concentration camps.

As Madeleine was not a French citizen, her sisters hid her in closets and laundry bags to keep her safe from arrest.

Then the sisters were separated. The younger ones went to the UGIF home at 9 rue Guy Patin in the 10th district of Paris, while Germaine was moved to the UGIF home at 9 rue Vauquelin on September 6, 1943.

Jacqueline and Madeleine were then placed with foster families in the Sarthe department of France. In all, they stayed with seventeen different families, but always stayed together.

Madeleine explained to us that they sometimes ended up in the homes of people who were not very kind, because in those days being a foster family was a source of income, so some people took in a lot of children just for the money.

For example, Madame Martin, whose son was a member of the Militia, took in fourteen children purely for the money. She put the eldest child of a family in charge of their siblings, gave them a daily ration of bread and sent them to school, or not, as she pleased.

The girls also met up with a social worker who provided them with the protection they needed.

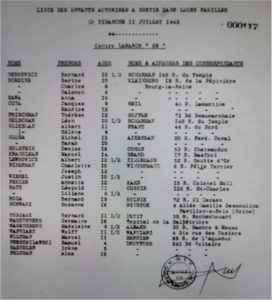

Extract from the UGIF register dated September 6, 1943

Extract from the UGIF register dated September 6, 1943

Source: The Shoah Memorial in Paris

Germaine had passed her primary school leaving certificate in May 1940. While living with in the UGIF home on rue Vauquelin, she began training to become a dressmaker, doing an apprenticeship with the famous fashion designer Lucien Lelong on avenue Matignon in Paris.

Germaine describes him as unpleasant and anti-Semitic. He was accused of collaborating with the Nazis, for which he was tried, but acquitted, in 1945.

While she was staying on rue Vauquelin, Germaine took part in various activities and went to the ORT school (The Society for Trades and Agricultural Labor) on rue des Rosiers in the 4th district of Paris. At weekends, she went to the French Jewish Scouts group on rue Claude Bernard in the 5th district. Both the ORT and Jewish Scouts were run by the UGIF during the war.

Germaine was well aware of the dangers faced by Jewish people in Paris during the Occupation. In 1942, for example, she remembers being stopped on the Champs-Elysées by a German soldier who was checking whether people were wearing their yellow star.

In July 1942, some police officers alerted Germaine to a forthcoming round-up, so that she could pass on the information. She sent Nono, her neighbor, to warn his family, including his uncle, aunt and a cousin. Nevertheless, her cousin’s wife and their little boy, Serge, were arrested.

On the outings register from the UGIF home on rue Lamarck dated July 11, 1943, we noticed that Germaine had been given permission to go to the Salpêtrière hospital. The mystery surrounding this outing was solved by Gilles, her son, and then Madeleine, her sister: Germaine went to visit her mother, who was in that hospital.

The UGIF register from rue Lamarck dated July 11, 1943

The UGIF register from rue Lamarck dated July 11, 1943

Source: The Shoah Memorial in Paris

Germaine also acted as a link between her sisters and her mother, writing reassuring letters so as not to panic anyone.

She probably decided not to tell them that Chaja had been arrested at the Rothschild hospital and deported to Auschwitz. Chaja, who was born in Poland in 1866, was arrested on November 6, 1942 and deported on Convoy 45 from Drancy on November 11, 1942. She never came back from the camps.

Ruchla, meanwhile, who had been admitted to the Rothschild hospital, was in trouble. In February 1944, one of Germaine’s childhood friends, a secretary at the hospital, told her that her mother was on the list of people to be arrested. Germaine enlisted the help of Monsieur Marcel, a resistance fighter who was hiding at the UGIF home on rue Vauquelin, to help her escape. The staff at the Rothschild hospital had a range of tricks up their sleeves to save the patients. Monsieur Marcel was able to get Ruchla out via the morgue, no doubt with a forged death certificate, as he had done with several other patients.

Ruchla then went to stay with a woman who sold newspapers at the Porte de Montreuil. She was told not to make too much noise, as the woman’s son was in the militia and if he discovered her in the attic, he might report her. Germaine therefore looked after her mother very discreetly, taking her food that Jacqueline sent from the country. She visited her every other day, and used to slip a subway ticket under the door so they knew it was her. Then when Germaine was arrested, her friend Rosette Berangol took food to Ruchla, she too slipping a subway ticket under the door.

Photo of Germaine taken in 1942

Photo of Germaine taken in 1942

Source: Gilles Hejblum

III – 1944-1945: The hell of life in the camps

In the dead of night, between July 21 and 22, 1944, the Gestapo arrested Germaine; the UGIF home on rue Vauquelin was targeted for a roundup on the orders of Aloïs Bruner, the commander of Drancy camp, who had all the children from UGIF homes in and around Paris arrested.

Germaine states in her testimony that only three people escaped the roundup in rue Vauquelin that night. All of the children, girls and staff were taken to Drancy internment camp.

Germaine recalls that the arrest and the journey to Drancy took place on a very hot day. When they arrived, they were met by the camp commander. The manager of the UGIF home on rue Vauquelin, Ms. Mortier, who had also been rounded up and spoke German, acted as interpreter. During their stay in the camp, the children were poorly cared for and hungry, and Germaine explained that the older children had to look after the younger ones. They had no idea where they were going next, but were simply told that families were to be grouped together in labor camps.

The journey to Auschwitz began on July 31, 1944 at the Bobigny railroad station, where the prisoners and their belongings were crammed into cattle cars. Germaine describes the journey as “horrible” and “the worst of all”. In the middle of the car there was a barrel containing some water, which was later used as a toilet. The sanitary conditions were appalling. The children screamed and cried, with no idea where they were going. The older ones tried to reassure them by telling them they were on their way to a place called Pitchipoï.

Three days later, the deportees arrived at Auschwitz in the middle of the night. They were herded onto the platform, shouted at and made to hurry off, leaving all their belongings in the cattle cars. Germaine remembers the dazzling light, the noise of dogs barking and Germans yelling, and also the unbearable smell. Only later did she realize that it was the smell from the crematorium.

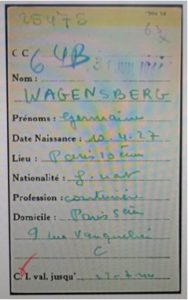

Drancy record card

Drancy record card

Source: The Shoah Memorial in Paris

With just a wave of their hand, the Nazis decided who would live and who would die. No children made it through the selection process. In their group, only one thirteen-year-old girl was chosen to stay in the camp. Germaine mentions the fact that she was tall for her age, and that she became the group’s “mascot”. Germaine also says that the girls were separated from Ms. Mortier, and that Rachel Honigmann, who was 21, hung on tight to her arm, refusing to let go. This scene remains etched in Germaine’s memory, as neither Rachel nor the manager passed the selection process.

Another memory left a strong impression on Germaine: when she was in Drancy camp, she bonded with a two-year-old boy, who she took care of on the journey. When she got out of the car at Auschwitz, a man in striped clothes took the boy away from her and put him on the ground. She says she didn’t know it at the time, but that the man probably saved her life, because no mothers with children got through the selection process.

Germaine, together with several other girls from rue Vauquelin, was selected to go to the work camp.

When they first arrived in the camp, everyone was put in quarantine. Next, the women were ordered to get undressed and were shaved all over, which they found unbearable. There was no sense of dignity or respect; men walked in and out of the room. They were then dressed in old rags and had numbers tattooed on their arms. Germaine’s number was A16827.

Once inside the camp, Germaine stayed with her friends from rue Vauquelin and her Scouts group. They remained close-knit in this hostile environment. The girls never had enough to eat. A small square loaf of bread was cut into pieces for eight people, who had to make do with that until the evening, when they were given a kind of thin soup.

The work they were made to do was exhausting and meaningless. They had to move stones, for example, and then put them back in their original place the following day. A selection process was carried out during the daily roll-calls, and sometimes even at night. Anyone who collapsed, exhausted, was immediately sent to the gas chambers.

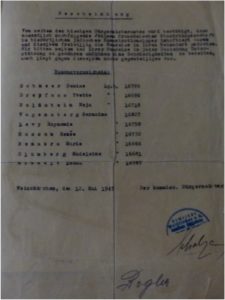

On October 27, 1944, Germaine and several of her friends were transferred to the Weißkirchen bei Kratzau kommando in northern Czechoslovakia, about twelve miles from Reichenberg. They had to walk four miles each morning to work in an aircraft factory, and back again in the evening. The winter of 1944 was awful and bitterly cold, and they had no proper clothing or footwear. They stayed in Kratzau until May 9, 1945.

They worked with some Italian prisoners of war who had contacts in the resistance movement. In the factory toilets, news, newspapers and apples were passed around. Germaine and her companions washed themselves as best they could under the tap.

In May 1944, Germaine, “Furet”, (Denise Schneer), “Gypsie” (Yvette Dreyfus) and some other girls were taken to the mountains to pack German weapons. Germaine’s friends had to remind her of this after the war, as she had forgotten all about it. Eventually, all the girls came back down from the mountains except Germaine, who continued to work up there on her own. A day or two later she too came back, and neither she nor her comrades were sent to the factory. It was a difficult month, as the Germans were annoyed and stressed out, having just lost the war.

IV – 1945-2020: The return to France

During the liberation of the camps, when the Soviet troops arrived in Kratzau, the Nazis, resistant to the end, kept the camp gates closed. They were finally opened on the evening of May 9.

The repatriation process was lengthy and laborious. Denise Schneer and Yvette Dreyfus went to the Kratzau town hall to ask the mayor for a permit to return to France. The group of girls had a tough time. Initially, they had to take sick people from the infirmary in tow, and then headed for Prague on their own.

The pass issued by the mayor of Kratzau

The pass issued by the mayor of Kratzau

Source: Yvette Levy

Germaine recounts how the girls were attacked on the road by British soldiers who intended to rape one of them. They struggled all night to defend themselves.

They then arrived at a barracks where, according to Germaine, they had to clean the toilets and were fed a diet ill-suited to the needs of deported women. They eventually taken back to Paris on an army train.

When she arrived at the Hotel Lutetia in Paris, not knowing where her mother was or who to contact, Germaine sent a telegram to her former English teacher, with whom she had been taking classes prior to her arrest.

The teacher alerted the staff at rue Vauquelin, which had become a shelter and where her mother and sisters were staying since their house and belongings had been confiscated.

In her testimony, Germaine’s sister Madeleine, who was a member of the committee responsible for assisting the deportees, explains that she ran down the street towards the subway in the hope of finding Germaine, just as a truck was driving up the street in the opposite direction. Suddenly, she heard someone shout “Madeleine!” It was her sister!

Germaine and her sisters were shocked when they finally met: she weighed only 68 pounds and her hair was cut short.

After they were reunited, Germaine went to stay with her mother and sisters on rue Vauquelin: they were the only women and the only mother there, which was mainly a home for boys. Her relationship with her sisters was sometimes difficult. From their point of view, Germaine was “unable to envisage what was to come”, and had never really left Auschwitz. This meant that no matter what the subject, she would always associate it with life in the camps. This led to a certain friction between Germaine and her sisters, and, according to Madeleine, their mother would sometimes say to them, “She was the one who deported. Her!”

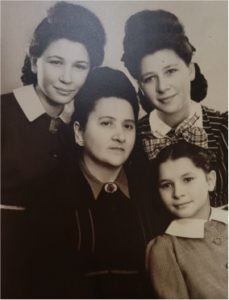

Ruchla and her daughters in January 1946

Ruchla and her daughters in January 1946

Source: Madeleine Wagensberg Germain

Once back home, Germaine tried to find their father. She discovered that he was in South America, where he had remarried and had children. He had filed for divorce in 1942, while he was in Cuba. Chilel returned to France for a short time in 1946. He took advantage of this visit to drop the divorce decree in their mailbox. The decree stipulated that he would pay Germaine alimony, although he never did so.

In August 1946, Germaine met Samuel Hejblum at a convalescent home in La Baule, on the west coast of France. He had been deported after the Vel d’Hiv roundup on Convoy 15, which left Beaune-la-Rolande on August 05, 1942, bound for Auschwitz.

Following this initial encounter, they sometimes ran into each other outside the Belleville subway station in Paris, as they lived in the same neighborhood. In April 1953, Samuel invited Germaine to have a drink at a café. While there, he invited her to the opening of the “Jardin de Montmartre”, a dance hall in the Montmartre district. They went dancing the very next afternoon, met up again the following week and soon became very fond of each other.

They got married on January 16, 1954 and had two children: Francine, who was born on August 27, 1954 in Paris and died on November 14, 2017, and Gilles, who was born on May 31, 1958, also in Paris.

Photo of Germaine, Samuel, Francine and Gilles in around 1962 or ‘63

Photo of Germaine, Samuel, Francine and Gilles in around 1962 or ‘63

Source: Gilles Hejblum

As Germaine explains in her testimony: “It’s revenge against Nazism to have started a family and to have grandchildren”.

After she got married, Germaine became a seamstress and she and Samuel started their own dressmaking business, which they called Elvy.

Their apartment at 83 rue de la Verrerie in Paris was devoted almost entirely to the business: there was no bathroom, and the children slept in a room with no window. The workshop had a cutting room where Samuel worked, as well as doing deliveries and the bookkeeping, while Germaine did the sewing.

In 1964, they moved to a larger, more comfortable apartment at 43 rue Turbigo. A few years later, their company went into liquidation and they then worked for a friend’s business.

In the early 1980s, Germaine and Samuel retired to Cannes. Samuel died in 2003. Germaine went into a care home in Nice in 2015. She died there during the Covid lockdown on April 16, 2020.

Germaine never wanted to return to Auschwitz. Her sister Madeleine went in 1989. According to Gilles, Germaine told her children very little about the deportation, no doubt not wanting to upset them. She did, however, give talks in schools and recorded an audio testimonial at the Alpes-Maritimes Departmental archives and a video testimonial at the Resistance Museum in Lyon. At a dinner in 2007, she met Simone Veil, who was also deported to Auschwitz.

Photo of Germaine meeting Simone Veil in Nice in 2007

Photo of Germaine meeting Simone Veil in Nice in 2007

Source: Madeleine Wagensberg Germain

Madeleine and Germaine

Madeleine and Germaine

Source: Madeleine Wagensberg Germain

Jacqueline’s wedding. Germaine on the left, behind Ruchla, and Madeleine on the right

Jacqueline’s wedding. Germaine on the left, behind Ruchla, and Madeleine on the right

Source: Madeleine Wagensberg Germain

Photos taken during Madeleine Wagensberg Germain’s testimonial on February 3, 2023 at the La Cerisaie school

Photos taken during Madeleine Wagensberg Germain’s testimonial on February 3, 2023 at the La Cerisaie school

Photo: Nathalie Baron

… and in 1965

… and in 1965

Source : Gilles Hejblum

Germaine and Samuel Hejblum, probably in the late 1950s

Germaine and Samuel Hejblum, probably in the late 1950s

Source: Gilles Hejblum

The second meeting with Gilles Hejblum on April 21, 2023

Photo: Nathalie Baron

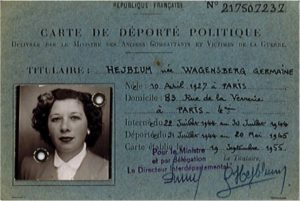

This card, which confirms that Germaine was deported for political reasons, is one of the records that served as the starting point for our investigation.

We are delighted to have been able to help ensure that all that remains of Germaine’s life is not just this one official document.

After enduring being deported, she had the strength to rebuild her life and start a family, which is something that we were not aware of when we began our research.

Germaine’s political deportee card, dated March 24, 1956

Source: Gilles Hejblum

Further reading: See the biographies of Necha Goldsztejn, Rosa Hofenung, Blima Krauze and Violette Parsimento

Français

Français Polski

Polski