Biography of Jean BENDER

This biography was researched, documented and written by two classes of 9th grade pupils from the Michel-Richard Delalande middle school in Athis-Mons, in the Essonne department of France, under the supervision of their teachers Clément Huguet, Déborah Le Pogam, Clara Adjanohoun, Laëtitia Legros and Valérie Virole during the school year 2018-2019.

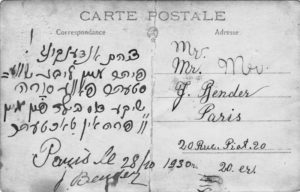

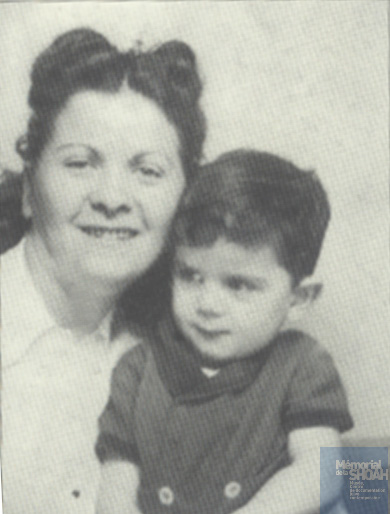

Photo of Jean with Gita, his mother (date unknown).

The Shoah Memorial / Serge Klarsfeld collection

Jean Bender was 4 years old in July 1944. This work, carried out by 9th grade pupils from the Michel-Richard Delalande middle school in Athis-Mons, during the school year 2018-2019, aims to tell his story along with those of his two sisters, Mina and Dora and his brother, Jacques.

Teachers’ notes

The story of the Holocaust is a one of destruction: of witnesses, of records and of evidence. We therefore wanted to show the students that this project could only ever lead to tentative, partial and non-absolute truths.

In writing this short chapter of history we could not reflect all the concerns raised by the students during their quest to retrace the life stories of these four children. For this reason, we asked them to imagine the type of conversations and thoughts that the family members might have had at various times in their lives.

These ideas, written in italics in the text, correspond to their own free interpretation of events. Alongside the scientific approach, they enrich the historical narrative by bringing in some of the feelings that students have expressed consistently and over the entire duration of the project.

Shattered childhoods

The lives of Mina, Jacques, Dora and Jean Bender were turned upside down in June 1940 following the defeat of France, the State’s collaboration with Nazi Germany and the adoption of anti-Semitic laws under the Vichy regime. The years that ensued shattered their childhood and innocence. It is their story that we would like to share with you here.

Before we began to write down the story, which is the tangible expression of our commitment to the European project Convoy 77, we carried out a historical investigation in order to better understand the context in which the story of the Bender children unfolded. To begin with, we consulted and analyzed all the available documentation in an attempt to retrace the journey of each family member.

Aside from this, we worked with the journalist Louise Gamichon, who gave us valuable advice to help us prepare for our meeting with Daniel Urbejtel, a survivor of Auschwitz-Birkenau. Daniel’s account moved us deeply and gave us a better understanding of his journey and the historical context. He shared some of his memories with us by telling us about his childhood, his deportation aboard convoy 77 and also his life after the Holocaust.

We also benefited from a three-day training course given by Christine Loreau of the Anne Frank House. We learned a lot about Anne Frank’s life and then became guides to an exhibition that was set up in our school for six weeks. As a result, over 900 5th – 9th grade students were shown around the exhibition. We were able to raise their awareness of the issue of anti-Semitism and share with them our knowledge about what life was like for children during the Holocaust.

In parallel with our historical investigation, we also devised and produced a sound documentary, which tells the story of Daniel and the four Bender children in a different way.

Through this project, we have become more socially responsible and committed students.

Chapter 1

In 1920, a young man named Josek Chaïm Bender arrived in France. He left Poland due to the anti-Semitism (systematic hostility towards Jews) and pogroms (violent attacks against Jews) that had begun to take place in his country. Following the murder of his father, Yitzhak, during a break-in in 1919[1], Josek Chaïm no longer felt safe and decided to flee Poland, leaving the other members of his family behind.

Josek Chaïm: Pawa Sura?

Pawa Sura: Yes?

Josek Chaïm: I have something to tell you. This isn’t going to be easy.

Pawa Sura: I’m listening.

Josek Chaïm: I’ve been thinking about it since our father died. I can’t stand the insults, the sudden, violent attacks, all the deaths, and all the people being killed… So that’ s why I’ve decided to leave….

Pawa Sura: I understand your fears but I can’t let you go away and leave our family.

Josek Chaïm: You don’t understand. One day it will be our turn.

Pawa Sura: Don’t say that.

Josek Chaïm: Since our father’s death, life has been very hard for us.

Pawa Sura: If you want to leave, then leave, but you must send us your news!

Josek Chaïm: Of course. I’ll say so long but not goodbye.

Pawa Sura: So long, brother.

In 1923, a young woman called Gita Goldstein arrived in France with her family. Her parents, Samuel Goldstein (born in 1890) and Jochwet Leibovitz (born in 1888), had also traveled across Europe to escape the social crisis in Poland and the increasing numbers of pogroms.

Jochwet: Samuel, what with the crisis and pogroms happening all around us, death will soon catch up with us – us and the children.

Samuel: I know, I think that too. I have a plan. My friends have a lot of contacts in Europe. We have a chance of surviving if we leave.

Jochwet: I…I…I can’t. My family has been living in Lodz for a long time. But still, you’re right, I know deep down inside that our survival is the only thing that matters.

Samuel: Don’t worry about it! We’ll go to Copenhagen to begin with.

Jochwet: Copen…where?

Samuel: Copenhagen in Denmark. It’s a country where we’ll be safe. And if it gets too dangerous there, we’ll go to Germany, where there’s a well-established Jewish community.

Jochwet: But… what about the children? How…?

Samuel: They’ll come with us! Stop worrying, they’re like me; they’re tough.

Jochwet: There’s no question of the children travelling in unsuitable conditions.

Samuel: If they don’t leave with us, their lives will be at risk here. We can’ t afford to wait any longer, we have to leave.

By the time Samuel and Jochwet arrived in France, they had had nine children born in various countries: three were born in Poland before 1914, five were born in Denmark between 1914 and 1920 and one was born in Germany in 1922[2]. Later on, they had three other children born in France. In 1927, they applied for French nationality and were naturalized in 1928[3].

Many others came to settle in France as they did, it having been the first country to have emancipated the Jews. A mutually supportive community then developed centered around Jewish culture and religion. Some had been in France for a long time and others had only recently arrived from Central and Eastern Europe. These people spoke Yiddish and lived in well-organized communities. Some were involved in federations founded in 1926 and others in trade unionism or even political activism.

Gita Goldstein became acquainted with Josek Chaïm Bender, who she married on January 10, 1928[4]. According to their marriage certificate, Gita was then a seamstress and worked in the same line of business as her father, Samuel, who was a tailor. Josek Chaïm was a packaging worker but also pressed clothes.

Their marriage led to the birth of four children who were called Mina (born June 28, 1930)[5], Jacques (born June 28, 1932)[6], Dora (born July 29,1935)[7] and Jean (born March 22, 1940)[8].

Gita and her son Jean (date unknown).

The Shoah Memorial, Serge Klarsfeld collection

Dora and her sister Mina.

Undated photograph.

The Shoah Memorial, Serge Klarsfeld collection

Their children were born French and Jewish and were raised in the Yiddish tradition, as shown by a postcard dated October 28, 1930. It was written, in Yiddish, by Josek Chaïm to his sister to announce the birth of his daughter, Mina. The parents therefore never abandoned their language and culture and kept in touch with those who had remained in Poland.

Photograph taken in October, 1930.

On the back, Josek Chaïm wrote in Yiddish “Remembering my dear sister Pawa Sura, I am sending you a picture of my daughter. Kisses.”

Goldstein-Bender family archive.

The card shown above is a photograph of Mina in her mother’s arms. She was 4 months old at the time. This photograph was probably taken in a professional studio: it is oval in shape, the background is black, Gita looks elegant, wearing a pearl necklace, and Mina appears to be supported by a tripod. Both of them are looking at the camera.

This is an unusual document because it was found in a closet in Australia in 2014 by Braham Zilberman. He is the grandson of Pawa Sura, who took refuge in Australia at the beginning of the Second World War.

We sought to trace the family’s journey through Paris in the 1930s. The birth certificates of Mina, Jacques, Dora and Jean reveal that the family moved from one address to another quite frequently.

When Mina was born in 1930, Gita and Josek Chaïm were living at 20, rue Piat and by the time their second child, Jacques, was born in 1932, they were living at 11, Faubourg Saint-Antoine. In 1935, when Dora was born, the family was living at 16, rue des Fossés Saint-Bernard and finally, when Jean, the youngest, arrived in 1940, they were living on the 3rd floor at 10-12, rue des Deux Ponts. Gita’s parents lived on the first floor of the same building, which was managed at that time by the Halphen Foundation.

At the outbreak of the Second World War, Josek Chaïm signed up for France as part of the 21st Marching Regiment of Foreign Volunteers [9].

On the left, Josek Chaïm Bender in the army (date unknown).

Goldstein-Bender family archives.

Josek Chaïm: Gita, I have to tell you something.

Gita: What is it?

Josek Chaïm: My desire to protect this country is so strong. That’s why yesterday I met with the man who recruits foreign soldiers to join the French army. The war has begun: it is time to defend France.

Gita: But… How… Why…?

Josek Chaïm: I have to leave tomorrow to start the training.

Gita: How am I going to tell the children that?

Josek Chaïm: I left a letter for each of them under their pillows. Gita, the reason I’m doing all this is to protect you and defend this country that offered us asylum, remember.

Gita: Yes, I know… Come back to us soon. Look after yourself. I love you.

Josek Chaïm: I’m so relieved that you understand. Thank you. I love you.

Chapter 2

Following the defeat of the French army and the signing of the armistice on 22 June 1940, Philippe Pétain and Adolf Hitler had a meeting in Montoire, on October 24. When the Vichy regime was established in July 1940, Philippe Pétain had set France on the road to collaboration with Nazi Germany.

From October 1940 onwards, the “first Jewish status law” was conceived and implemented. This took away many of the Jews’ rights and banned them from working in various professions and from continuing to work in the public sector.

A series of exclusionary measures were introduced, such as restrictions on access to certain public places. Through the census, the police were able to obtain information on the composition of Jewish families and their places of residence.

In November 1941, l’Union Générale des Israélites de France (UGIF) a grouping of Jewish assistance initiatives, was created by the Vichy regime at the request of the German authorities. A number of children’s homes in the Paris area were run by UGIF, which took in children of all ages and from very diverse backgrounds. Some of them were orphans, while others were sent there by their parents, no doubt in the hope of protecting them.

This was what happened to Mina and Jacques, who were placed in the Varenne center by their mother, probably in 1942, but they refused to accept this and escaped from the center to return to their family home.[10]. As for Dora and Jean, they were also placed in UGIF homes, notably those on rue Lamarck and on avenue Secrétan[11] but it is difficult to retrace their steps exactly.

Jacques: Mina? Are you asleep?

Mina: No, I can’t get to sleep.

Jacques: I’m starting to have had enough of staying here.

Mina (sighing): I understand, but what are you going to do about it?

Jacques: I have an idea. An escape plan!

Mina: You want to run away from here?

Jacques: And why not? I’m getting fed up with it! Because I wear a stupid star, I will never be allowed to live a normal life. If that’s what Jews are expected to endure, then I refuse.

Mina: But where are we going to go?

Jacques: I haven’t really thought about that. Anyway, come with me tomorrow, early in the morning, we’ll have a chance to escape.

Mina: Okay, I’ll come with you, even though I’m scared,

Mina and Jacques escaped from the UGIF center the following day. As soon as they were out, they took off their yellow stars.

Mina Bender (in the first row, just above the green cross) in 1942, in a children’s home located at the foot of Sacré Coeur in Paris.

Serge Klarsfeld / Fils et Filles des Déportés Juifs de France (FFDJF) Sons and Daughters of Jewish Deportees from France

In fact, after the publication of the 8th German Decree of 29 May 1942, Jews over the age of six were required to wear a yellow star.

The photograph below, taken in August 1942 thus shows Dora Bender, sitting in the front row, surrounded by other children, many of whom are wearing yellow stars. Dora did not have to wear one because she was only 6 years old at the time. On another document there is a photo of Mina and Jacques with their yellow stars sewn on to their clothes. They appear to be cheerful and close to one another.

Mina et Jacques.

Undated photograph.

The Shoah Memorial, Serge Klarsfeld collection.

Dora in the first row, 7th from the left.

Shoah Memorial, Goldstein collection

When faced with wearing a star, which was intended to be stigmatizing and discriminatory, some children had mixed feelings. For example, Hélène Berr refused to wear a star at first because she considered it an insult and thought it would be proof of her compliance with the German rules. She finally decided to wear it, however, and sometimes felt comforted by the sympathetic looks that people gave her[12]. Annette Muller also testifies to the shame she herself felt when her friends rejected her because she had to wear a yellow star.[13].

Jacques: Mina, where’s my sweater with the star on it?

Mina: Why? Do you really want to wear the star?

Jacques: Yes, I’ll wear it, because remember what mom said, it’s a requirement for us Jews. And even though I’m ashamed of it, I‘ll wear it.

Mina: Why are you ashamed of it? Is it because of other people?

Jacques: Yes, I don’t like it when people see me wearing it.

Mina: I understand. I know how you feel.

On January 11, 1943, the Goldstein-Bender family was investigated by the Prefecture of Paris Police with a view to securing their denaturalization[14]. By removing their French nationality, the Vichy regime was attempting to isolate Jews from the rest of the population and deprive them of their freedoms. However, the Goldstein-Bender family members were not denaturalized because several of them, including Josek Chaïm, had enlisted in the French army at the beginning of the war.

Chapter 3

On January 20, 1942, at the Wannsee Conference, the “final solution of the Jewish question” was approved. It was in this context that the Nazis decided to systematically exterminate over eleven million Jews in Europe.

Even before that, the Vichy regime had been collaborating with Nazi Germany and making arrests on French soil. On May 14, 1941, the French police organized the “green card” roundup. Foreign Jewish men were sent green cards summoning them to police stations for an “examination of their administrative situation”, hence the name ‘green card’ roundup. In reality, this summons was just a pretext for their arrest.

It was on this occasion that Josek Chaïm was arrested and taken to Austerlitz station. He was transferred to the Pithiviers camp in the Loiret department, later that same day[15]. It was a transit camp made up of wooden huts.

Josek Chaïm was given the number 66 and was first assigned to barrack 14 and then to barrack 8. [16]. Like the other internees, he had no idea what to expect or how much time he would have to spend in this camp.

Some internees were able to go to work outside the camp: Josek Chaïm, for example, was assigned to a farm as an agricultural laborer in August 1941. He later worked in the Pithiviers sugar factory, which was located just outside the camp, from October 1941 to April 1942[17].

Family visits were allowed, thus Gita was granted permission to visit her husband on 16 June 1941, accompanied by one of their children[18].

French police officer: Hey you, Bender, you have visitors!

Josek Chaïm: It’s great to see you! Quick, give me all the news. Tell me, how you are doing? I don’t have much time! How are the others?

Gita: They’re fine, they’re safe. Here, this is for you, a little something to improve your day-to-day life. Why don’t you tell me how things are going here? Are they treating you well?

Josek Chaïm: You’re so far away from me. But I’m trying not to complain. Tell me more about the children.

Gita: Josek, do you know what’s happening?

Josek Chaïm: They tell us nothing. There are rumors… There’s no point in talking about it just now.

(To the child): What about you Honey, how are you?

The child: We’re worried about you Dad; we miss you. Here, this is for you. I wanted to ask you…

French police officer: Visit over! It’s time to go now.

Gita: Already?

Josek Chaïm: We’ll see each other again soon! Don’t worry. Goodbye my darlings! See you soon!

The child: Bye Dad!

Gita: Look after yourself! I’ll come again as soon as I can.

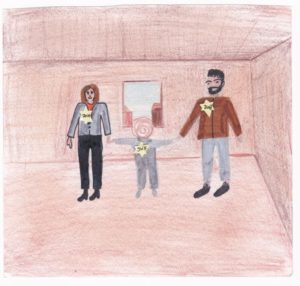

Gita and one of their children visiting Josek Chaïm at the Pithiviers camp.

Drawing by Sofia

After a bombardment in April 1944, the children were transferred from the UGIF Center on Avenue Lamarck (in the 18th district of Paris) to the Secrétan Center (in the 19th district). Tauba, their aunt, worked there as a maid.[19], which Gita found reassuring.

A few months later, to keep them out of harm’s way, many of the children were smuggled out of Paris and sent to live on outlying farms. Mina was sent to Montereau, southeast of the capital, to be hidden on a farm. She pretended to be a Catholic. Her brothers and sisters were to join her but not mention that they were Jews.

However, on July 22, 23 and 24, 1944, the Gestapo organized roundups in the UGIF centers in Paris. Jacques, Dora and Jean were thus arrested, as were nearly 300 children aged from 2 to 15[20]. They were caught in the trap.

Jean: Where are we going, Jacques?

Jacques: I don’t know but stay calm, don’t worry.

Dora: (holding back tears): You know very well… You know where we’re going.

Jacques: Dora, I assure you, I don’t know what’s in store for us. Try to stay positive (his voice starts to crack.

Dora (almost sobbing): I’m scared and Jean’s crying.

Jacques (squatting down to look his brother and sister in the eyes): Come here, I want to whisper something into your ear. Nothing will separate us, we’re together, and we’ll stay together.

Jean, dry your tears, we’re nearly there. Oh look, there’s Tauba!

Tauba comes up to the children discreetly.

Tauba: Children, here you are at last!

She gives them all a hug.

They were all transferred to the Drancy camp, on the site of the city of La Muette. When war broke out in France in 1940, the city was unfinished and was hurriedly converted into a prison camp. It became a transit camp in August 1941 and Jews who had been arrested were held there until they were deported.

The camp, under the supervision of the French police, was surrounded by barbed wire and watchtowers. The buildings formed a U shape, and although the structural work had been completed, nothing had been done to improve the interior[21]. There was only one water point for the entire population of internees, who were living in difficult and unhealthy conditions. Discipline was very strict. Separated, lost and sick children lived in fear[22].

Upon arrival, everyone was taken to a search hut at the end of the courtyard, where all their personal belongings were confiscated. They were also registered there.

Jacques, Dora, Jean and their aunt Tauba were first put in bedroom 4, on staircase 4, and then moved to bedroom 2, on staircase 6[23].

French police officer: Come forward and put all your belongings here.

Tauba (whispering): Go on children, do as he says.

Jean: Do you think I can keep my teddy bear?

Tauba (smiling and giving him a hug): Yes, my darling.

French police officer: Head for stairwell 4, you’re in room 4.

Dora (going up to her aunt): Where are we going to sleep? There are so many people!

Tauba: Don’t worry. Look, we’ll find a place.

Staircase 4, room 4: They didn’t know it yet, but their fate was already sealed.

Chapter 4

Josek Chaïm was “handed over to the occupying authorities” on June 25, 1942. He was deported the same day, from Pithiviers station to Auschwitz-Birkenau as part of convoy No. 4[24]. He was never to return home, assassinated at the age of 41 in the gas chambers.

Josek Chaïm was one of the first Jews to be deported from France to this killing facility. The implementation of the “final solution” had begun. In fact, in anticipation of the major round-ups of July 1942, in particular that of Vel’d’Hiv, the transit camps were cleared of all their inhabitants.

On July 31, 1944, Jacques, Dora and Jean were deported from Drancy-Bobigny on convoy 77, one of the last to leave for Auschwitz-Birkenau. Like Daniel Urbejtel, they were among the last people to be deported from France in the cattle wagons.

“We saw a train. Not a passenger train but a train made up of freight cars! Those wagons were not made for passengers”[25]

The journey to Poland took three days. Conditions for the deportees were appalling: the cramped wagon had only a few air vents which were covered by barbed wire. There was only one bucket of water and another to serve as a toilet.

The heat was infernal and the train stopped regularly in full sunlight, with insufficient water for the deportees to drink.

There is also the fear, anguish and tears of separated children who were clamoring for their parents.

In the wagon, two days into the voyage, amidst the shouting, crying and wailing…

Jean: Jacques, I need to pee.

Jacques: Jean, there aren’t any toilets. I heard someone showing someone a bucket. You’ll have to use that.

Jean: Where’s Mom?

Jacques does not answer.

Dora: Jacques, do you have any water? I’m thirsty.

Jacques: There’s a little at the end of the wagon.

Dora (clinging to his brother and whispering in fear): Jacques, I think the person next to me is sick.

Jacques: Why do you say that?

Dora: She’s not moving any more. I think she’s dead.

Jacques: No, Dora. (He puts his arms around her) She’s asleep.

Some people did not survive the journey. Those who made it to Auschwitz-Birkenau had to face the brutality of the Nazis and their dogs when they got off the train.

As the train arrives, the children screaming and crying…

Jacques: Don’t worry, we’ll get through this.

Jean is crying. He’s afraid.

Dora: Jean, calm down.

The train comes to a sudden halt. Orders are shouted in German.

Jacques: I think we’ve arrived.

The doors open.

Jacques: We’ll stick together! No matter what happens!

They all hold hands.

When the doors opened, the deportees got off the train on to the selection ramp. They were then sorted into two groups according to their age and ability to work.

The first group was made up of persons deemed fit for work who were later used as forced labor. They were assigned barracks, in which there were wooden bunk beds but no mattresses or pillows.

The second group was made up of all those whom the Nazis considered unfit for work: children and those who were elderly, sick or weak. These people were killed, from the day they arrived in the camp, in the gas chambers.

Daniel Urbejtel, who was deported in the same convoy as the Bender children, was found fit for work thanks to his older brother, who told him to stay by his side.

“My brother went ahead of me and was sent to the side with the men (…) Against all odds, I was also sent to the men’s group.” “One thing is certain though: if I had had the freedom to choose my group, I would have chosen (…) the one that Bernard and his cousins Jacques, Dora and Jean were in”[26]

A Nazi soldier: @-(`/;.,°) !! _;(*`(« _ !

Dora: He’s scaring me.

Jacques: Don’t worry. Stay behind me.

Jean: I want my Mon, where’s Mom? I’m tired and hungry.

He starts to cry.

Jacques: I don’t know. He can hardly speak with the lump in his throat.

Jean: Where are we going, Jacques?

Jacques: I don’t know, let’s follow the others.

Jean: Oh Tauba! He wants to rush over to his aunt but Jacques holds him back.

Jacques: Stay beside me Jean. Don’t worry, we’ll catch up with her later, we’re in the same group.

Dora, happy to see a familiar face, wants to run to her aunt too.

Jean: Auntie, auntie…

She turns and looks towards them.

Jean: Auntie, where’s Mom?

The Nazis then took the deportees deemed unfit for work towards the far end of the camp. There they had to undress and were herded into to rooms that looked like communal showers. They were in fact gas chambers.

When the doors closed, they were murdered using a gas, Zyklon B. They died of asphyxiation.

The Sonderkommandos, forced laborers who were themselves Jewish deportees, were responsible for sorting the personal belongings of the murdered deportees and taking the bodies to the crematoriums, where they were then incinerated. The ashes were scattered near a lake in the woods.

Ten members of the Goldstein-Bender family passed through the gates of the Auschwitz-Birkenau killing facility. Of these ten, eight had their lives cut short: Josek Chaïm Bender and his three children, Jacques, Dora and Jean; Thérèse and Sonia Goldstein, the children’s aunts and Bernard and Daniel, the children’s cousins.

Apart from Josek Chaïm, who was deported on convoy No. 4, and Elieser Goldstein, who was deported on convoy No. 61, they were all deported on convoy 77 on July 31, 1944

Only Sonia’s husband, Wolf Goldstein, and her brother, Elieser Goldstein, survived.

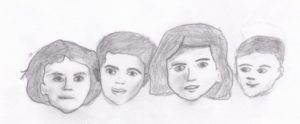

Dora, Jacques, Mina and Jean Bender.

Drawing by Emma.

It is not known when exactly Mina returned to Paris after the Liberation of France.

On the other hand, we do know that her mother, Gita Goldstein, stayed at 10-12, rue des Deux-Ponts in Paris and was still living there at the end of the war.

In 1948, she applied for deportation certificates from the Ministry of Veterans and Victims of War[27].

In 1951, she also submitted applications for the title of political deportee for each of her three missing children[28]. The Ministry took the decision to grant this on November 5, 1954[29].

Lives destroyed… but the fight goes on

Our school was awarded The Ilan Halimi prize for this project, which has been underway since last year. Our school was awarded The Ilan Halimi prize for this project, which has been underway since last year. The award is a tribute to the work done by the students last year and that which has continued this year.

Prior to this, we had not heard the story of Ilan Halimi, a young man who was kidnapped, tortured and left for dead near a railway line in Sainte-Geneviève-des-Bois in January 2006. Based on a stereotype that dates back to the Middle Ages, Ilan’s tormentors thought he must be rich simply because he was Jewish.

His tragic and moving story shocked us and made us think about the stereotypes associated with different groups of people.

The anti-Semitic attacks of the past few months, in which trees planted in memory of Ilan have been cut down and uprooted and Swastikas were drawn on portraits of Simone Veil, have made us realize that the fight against intolerance, racism and anti-Semitism must be continued.

The work we have done this year has enabled us to retrace the journey and write the story of a family devastated by the Holocaust.

Mina, James, Dora and John’s childhood and innocence were shattered, simply because they were Jews. This should not have happened and we must never let it happen again.

We in turn are now committed to fighting racism and anti-Semitism. Thus, inspired by the example of Otto Frank, Anne Frank’s father, we took it to heart and appealed to our comrades about the need to work together to combat discrimination.

Today, through this work, we are joining those who are committed to writing the stories of the victims of the Holocaust, the few remaining survivors of which are inevitably fading away.

It is our turn to pass on this history to the next generation.

Contributors: Two classes of 9th grade pupils from the Michel-Richard Delalande middle school in Athis-Mons, in the Essonne department of France, under the supervision of their teachers Clément Huguet, Déborah Le Pogam, Clara Adjanohoun, Laëtitia Legros and Valérie Virole, during the school year 2018-2019

Notes:

[1] Witness statement of Braham Zilberman, the grandson of Pawa Sura (Josek Chaïm’s sister), taken in October 2018.

[2] Application for naturalization filed in 1927 by Samuel and Jochwet Goldstein. National Archives of France.

[3] Naturalization decree with reference number 3140 x 25, National Archives of France.

[4] Marriage certificate of Josek Chaïm Bender and Gita Goldstein, issued at the Town Hall of the 4th district of Paris on January 10, 1928. City of Paris Archives.

[5] Birth certificate of Mina Bender, issued at the Town Hall of the 12th district of Paris, on June 28, 1930. City of Paris Archives.

[6] Birth certificate of Jacques Bender issued at the Town Hall of the 4th district of Paris on July 28, 1932. City of Paris Archives.

[7] Birth certificate of Dora Bender issued at the Town Hall of the 14th district of Paris on July 29, 1935. City of Paris Archives.

[8] Birth certificate of Jean Bender issued at the Town Hall of the 14th district of Paris on mars 1940. City of Paris Archives.

[9] Ministry of the Armed Forces (www.memoiredeshommes.sga.defense.gouv.fr) and Shoah Memorial (UEVACJEA records).

[10] Witness statement of Mina Bender, taken in December 2018.

[11] Record of interview with Gita Goldstein, carried out on October 27, 1952. Service Historique de la Défense, Division des Archives des Victimes des Conflits Contemporains (Ministry of Defense Historical Service, Office of archives of victims of contemporary conflicts), File N°63.108 (Jacques Bender).

[12] Hélène BERR, Journal (1942-1944), « Jeudi 4 juin, 1942 », Points, 2009, p. 54.

[13] Annette MULLER, La petite fille du Vel d’Hiv, Editions Denoël, 1991.

[14] File concerning the investigation by the Prefecture de Police, dated January 11, 1943. Prefecture of Police of Paris Archives.

[15] Extract from the Pithiviers file, Loiret Departmental Archives.

[16] File concerning the internment of Josek Chaïm Bender at the Pithiviers camp, Pithiviers file, Loiret Departmental Archives.

[17] Individual account records, Pithiviers file, Loiret Departmental Archives.

[18] Extract of the table showing visitors permits, Pithiviers camp, June 16, 1941, Pithiviers file, Loiret Departmental Archives.

[19] See the biography of Tauba (Thérèse) Goldstein at: http://www.convoi77.org/deporte_bio/tauba-goldstein/

[20] Raphaël ELMALEH, Une histoire de l’éducation juive moderne en France : l’école Lucien de Hirsch, édition Biblieurope, 2006, p. 190.

[21] Annette WIEVIORKA, Auschwitz expliqué à ma fille, Seuil, 1999, p. 22.

[22] Jean-Pierre GUÉNO (dir.), Paroles d’étoiles. Mémoires d’enfants cachés (1939-1945), Librio, 2002.

[23] Files of Jacques Bender, Dora Bender and Jean Bender, Drancy camp, July 22, 1944. National Archives/Shoah Memorial, Paris. Drancy children records F9/5742

[24] Extract of the deportation register for convoy N°4, The Shoah Memorial, Paris.

[25] Witness statement of Daniel Urbejtel, December 12, 2018.

[26] Witness statement of Daniel Urbejtel, December 12, 2018.

[27] Folders N°63.108 (Jacques Bender), N°63.109 (Dora Bender) and N°63.110 (Jean Bender). Service Historique de la Défense, Division des Archives des Victimes des Conflits Contemporains (Ministry of Defense Historical Service, Office of archives of victims of contemporary conflicts), 21 P 423.

[28] Ibid.

[29] Ibid.

Français

Français Polski

Polski

[…] Lire la biographie de Jean Bender […]

[…] http://convoi77.org/deporte_bio/jean-bender/ […]