Maurice SALOMONOVITCH

This project was carried out by a class of 12th grade students at the Maurice Ravel high school in the 20th district of Paris, France, during the 2023-24 school year, under the guidance of their history teacher and homeroom teacher, Philippe Landru. Comprising some thirty students, the class split into three groups to work on three different biographies as part of the Convoy 77 project. Ten students worked on this biography of David and Maurice Salomonovitch. This year-long assignment was also their ethics and civic education project, which was assessed as part of their French baccalaureate exams.

The Convoy 77 project team initially assigned us the task of writing the biography of one man, David Salomonovitch, who was born in Paris in 1909 and, after having been interned in Drancy, was deported to Auschwitz on July 31, 1944. When we began to search the civil registers and census records for Paris, we discovered two things, and soon realized that we were going to have to broaden the scope of our research enormously:

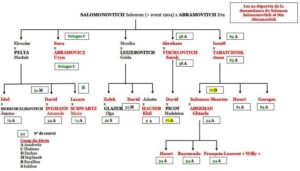

- The first was that the Salomonovitch family was a very large one, and we were able to follow them from register to register. Born in Russia-occupied Poland at the end of the 19th century, an entire sibling group emigrated to Paris early in the 20th century.

- The second was that we could not make much progress unless we carried out comprehensive analysis of the family tree: not only did the same first names occur again and again, with some names spelled differently from one record to the next, but this pattern of first names was further complicated by the random use of one first name of Hebrew origin, which varied greatly according to the authorities’ interpretation of the accents, and a second that was “Frenchified”, often to disguise its Hebrew origin. There were also some names that were not listed in the civil register at all, but just used within the family[1]. Had we not made this exhaustive list, there would inevitably have been considerable confusion between the various branches of the family.

It soon became clear, therefore, that we were embarking on a family monograph that went far beyond the story of this one individual, David. As our research progressed, we discovered that twenty-two members of the family were deported from France, the youngest of whom was under two, on eleven different convoys. Only one of the 22 survived and made it home from the camps! Two of them, including “our” David, were deported on the last transport from Drancy, shortly before the camp was liberated: Convoy 77.

We went through all the Parisian civil records to find all the Salomonovitch family members in all the districts of Paris from 1883 onwards, as far as possible within the limits of the online archives. Virtually all of them are related to the branch discussed below[2].

What follows is the fruit of a considerable amount of work, not without its pitfalls, but which we found both moving and fascinating.

I- FROM POLAND TO FRANCE: the first two generations

- Their Polish roots

- The move to France

II- KHOUDES (c1867-1930) AND THE PELTA BRANCH

III- EMMA (1872-1955) AND THE LAUFER FAMILY

IV- MORDKA (c1873-1932) AND HIS DESCENDANTS

- Jules (1891-1943) and David (1898-1943), the two oldest sons

- David’s descendants: unravelling a mystery about a record from the Shoah Memorial

- The war: house arrests and deportation of Jules and David

- Juliette (1900-1981) and Khil Hauser

- Salomon Maurice (1903-1981)

- Anna (1906-1947)

- Léon (1907-1992)

- Isaac “Jean” (1910-1989)

- Joseph (1914-1996)

V- ABRAHAM (1883-1943) AND HIS DESCENDANTS: David Salomonovitch’s branch

- Abraham and Sarah: his parents

- Ferdinand, Isaac and Juliette: his brothers and sister

- David himself (1909-1944)

VI- ISRAËL (1885-1943) AND HIS DESCENDANTS: A BRANCH DECIMATED BY DEPORTATION

SOURCES – THANKS

The 18th district of Paris – Wikipedia

The 15th district of Paris – Wikipedia

I – FROM POLAND TO FRANCE: THE TWO FIRST GENERATIONS

1. Their Polish roots

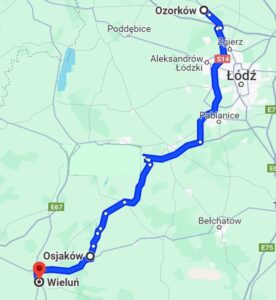

The Salomonovitch family hailed from the Łódź region, a part of Poland that was occupied by the Russians in the early 20th century. More specifically, two places, some 10 miles apart, represent the family’s “homeland”: Osjaków (often spelled Osiakov, but also Tousiakeff, Assiakero, Assiakers…) and Wieluń (which in the archives, including those of the Shoah Memorial and on the Yad Vashem website, is spelled in numurous incorrect ways): Vieloune, Vielanne, Jelanne, sometimes Vjsbonne, and even Nephonne or Williom in the Vincennes archives!).

Wieluń in 1939, after it was bombed

Source: fr-academic.com

Both had significant Jewish communities, particularly Wieluń, an important trade and manufacturing center where Jews had been present since the beginning of the 16th century and by 1939, made up half of the population [3]. At 4.40 a.m. on September 1, 1939, it was the first Polish town to be bombed by Luftwaffe, and some 80% of it was destroyed. The region, which had been repeatedly occupied by foreign powers, had also been the setting for numerous pogroms, and anti-Semitism was rife.

This was no doubt why, coupled with their search for a better life, the Salomonovitch family emigrated to France.

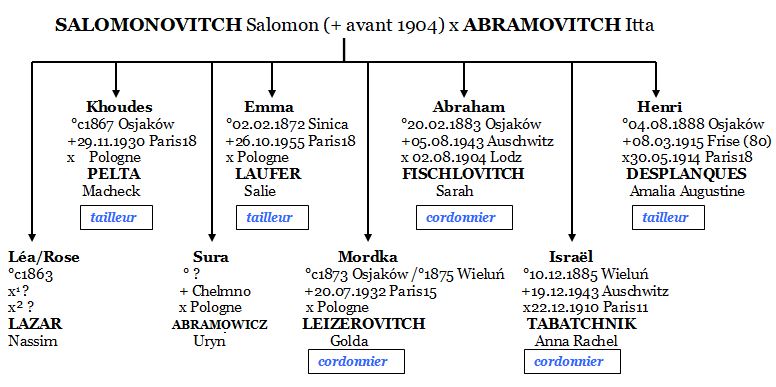

The earliest ancestors we know of were Salomon (sometimes spelled Chloma, even Chlionna), who was married to Itta/Ida/Hannah/Anne Abramovitch[4]. We know very little about them except that they died in or before 1904. We can thus confirm that, with the exception of Emma, the Salomonovitch siblings only left Russian occupied Poland after their parents died.

Salomon and Itta had a large number of children, almost all of whom eventually made their way to France. We will begin by listing the six for whom we have documetary evidence:

- Khoudes (Choudessa in some official documents), who was born around 1867 in Osjaków, and who may have been the eldest daughter, whose descendants we will discuss in section II.

- Emma, who was born on February 2, 1872 in Sinica, Poland[5] and it was there that she married Salie Laufer. Whe shall come back to them in section III.

- Mordka [6] (also sometimes spelled Modka, Mordko and Mordko Leil, or even Léon), who was born between 1873 and 1879 in Osjaków. He married Golda Leizerovitch in Poland, and it was he who had the greatest number of descendants; eight children born between 1891 and 1914, the first six of whom were born in Wieluń. HIs son Léon, who was born there in 1907, was the last Salomonovitch of the French branch to be born in Poland. Two of his sons were deported. We will focus on this branch of the family in section IV.

- Abraham, who was born on February 20, 1883 in Osjaków: he was the father of David Salomonovitch, born in 1909, on whom our Convoy 77 project was to focus on initially: we shall look further into this line in section V.

- Israël, who was born on December 10, 1885 in Wieluń. He married Anna Rachel Tabatchnik in Paris in 1910. This branch of the family suffered the most during the Holocaust, as it appears to have been completely wiped out. We shall cover their story in section VI.

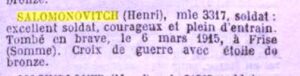

- Henri, who was born on August 4, 1888 in Osjaków. A dressmaker by traded, he was living at 6 avenue des Tilleuls on May 30, 1914, when he married Amélie Augustine Desplanques, a seamstress from Trouville-sur-Mer, in the Calvados department of France[7]. At the same time, he declared that he was the father of a daughter, Andrée, who was born in the 11th district of Paris in 1911[8]. Their relationship was short-lived, however: when the First World War began in 1914, as he was a Polish citizen, he joined the French Foreign Legion. A 2nd-class private in the 7th company of the 2nd battalion of the 3rd foreign regiment infantry regiment (regimental number 3317), he was killed by a bullet to the head[9] on March 6, 1914, while fighting on the front line in Frise, on the Somme. He was awarded the French War Cross with bronze star. His name is inscribed on the War Memorial in Paris, on the wall of the Père Lachaise cemetery.

French official gazette, October 5 ,1919

Andrée, who was born in the 10th district of Paris on May 25, 1911, was the couple’s only child. She never married or had children, and died in Avon, in the Seine-et-Marne department of France, on May 30, 1994.

It would be remiss of us not to mention a police report about Abrahams family which was issued on November 12, 1929, when he applied to be naturalized as a French citizen. This report, which lists Abraham’s brothers and sisters among other things, hardly seems reliable: it includes Khoudes, who it says was 70 years old, which would mean she was born around 1859 (!), and then goes on to say “Léon, 50 years old, shoemaker, 10 impasse Ribet, Izendar, 30 years old, shoemaker, 23, rue Juge and Léa, 55 years old, remarried to a French citizen, no occupation, 24, rue Leibnitz”. The fact that the report refers to Khoudes (b. 1859) as the sister of Izendar (b. circa 1899), i.e. a forty-year age difference them, shows how sloppy the police were in their research. But what can we make of this data?

- As regards Léon, there is no doubt: this was Mordka Leil. He was indeed living at 10 Passage Ribet in the 15th district at the time, and was a shoemaker (according to the 1926 census, he was born in 1873). In the 1931 census, he is even listed as Leile.

- Modka/Mordko/Leil/Leile/Léon: we can clearly see from this how changeable first names could be. We we have no way of knowing exactly which one was actually used by family and friends at the time, however.

- As for Izendar (who the report says was born in 1899), in reality, this must have been Isaac (who was in fact born in 1885). He was the one who lived at 23 rue Juge in the 15th district, as confirmed by the 1926 census.

- Léa, the only trace of whom is to be found in the 1926 census, was listed as living at 24, rue Leibniz. It says that she was born there in 1863 (which would make her the eldest of the siblings), that she was a widow and that she was living with a man by the name of Nassim Lazar. We do not know what happened to her after that. However, Nassim’s death certificate, dated 1939, which we found in the civil registry in the 18th district, suggests that although they were living together, they never married.

That just leaves Sura. We know almost nothing about her, because she never moved to France. What little we do know is that she married Uryn Abramovicz, a butcher, with whom she had a large family, including Golda, who married her cousin Maurice Salomon Salomonovitch in France, and Fradla, whose daughter Estera married André Salomonovitch. Most of the Abramovicz family, which forged several family links with the Salomonovitch family, stayed behind in Poland, where they were decimated by the Holocaust. Sura Salomonovitch and her husband Uryn were exterminated in Chelmno[10]. Was Sura one of the sibling group that we are researching? We cannot say with absolute certainty, although it is highly likely. Present-day family members believe so.

Sura Salomonovitch – Family photo

2. The move to France

When did Salomonovitch family first arrive in France? According to the present-day family, the story goes that the men arrived first to look for work, and then their families followed: a classic migratory pattern. What happened in reality, however, may have been more nuanced: the eldest of the siblings were women, who were already married when they arrived in France. When he applied to be naturalized as a French citizen, Abraham stated that he had arrived in France in 1904. In any case, we can safely say that the family migrated very early on in the 20th century.

Mordka’s son Léon, who was born in Wieluń in 1907, was the last of any of the branches of the family to be born in Poland, while Emma’s son, Maurice Laufer, who was born in the 18th district of Paris in 1900, was the first to be registered in France.

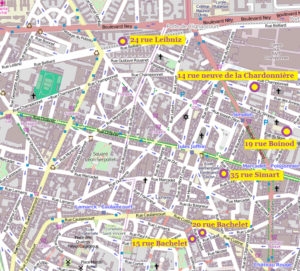

Although the early Salomonovitch records in Paris originate from various different districts, it was not long before the family clustered together in the 15th district. This is quite unusual, given that the most Jewish immigrants settled in the 4th, 11th, 19th and 20th districts of Paris. There are two possible explanations for this: the family moved nearer to those who had arrived in France first, and the fact that the Salomonovitch family were almost all tailors, shoemakers or seamstresses. It would have been easier to find customers in the densely populated, better-off 15 th district than in the more traditional Jewish neighborhoods, which were generally in poor areas.

II – KHOUDES (1867-1930) AND THE PELTA BRANCH

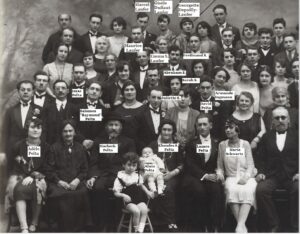

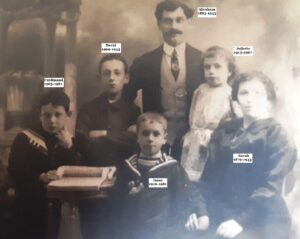

Family photo – taken in around 1918

Born in around 1867, according to her death certificate, Khoudes may have been the eldest of the siblings, unless perhaps Léa, or even Sura, came first. She married Macheck (also known as Moïse, Mochel or Nolisk) Pelta and the couple went on to have four sons, all of whom were born in Poland between 1895 and 1904. Early in the 20th century, the Pelta family was one of the first branches of the family to emigrate to France. They initially lived at 15, rue Bachelet, in the 18th district of Paris[11], and later moved to Montreuil-sous-Bois, in the Seine-Saint-Denis department. Khoudes died at 15, rue Bachelet in 1930. She and was buried on December 1 in the Bagneux cemetery in Paris, in what was to become the principal burial place for the family[12].

This branch of the family was particularly hard hit during the war:

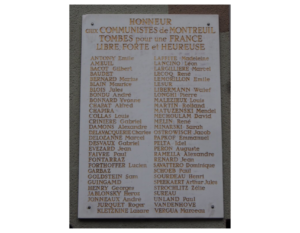

- Idel Isaac Pelta, who was born in 1895 in Osjaków, married Jeanne Herschcelikovitch on April 12, 1920 in Montreuil[13]. He was a tailor at the time. We do not know if he ever married or had children[14]. During the Second World War, he joined the French Resistance movement and because a member of the Front National[15], a communist group. After being arrested and interned in Drancy camp[16], he was deported from Bobigny station on May 30, 1944, on Convoy 75 (there were 1004 names on the manifest) and arrived at the Auschwitz-Birkenau camp on June 2. At the age of 49, he appears to be one of the 624 people from this transport who were sent straight to the gas chambers and murdered. His name is inscribed on a commemorative plaque in Montreuil, which pays tribute to local communists who gave their lives for France.

Source: Geneanet

- David Pelta, who was born in 1897 in Osjaków, married Armande Igmann on June 8, 1926 in the 18th district of Paris. He was tailor by trade, as was his brother (and various other family members). We discovered that the couple had a son, Alain Bernard, who was born on May 17, 1930 in the 10th district of Paris, but died the following year, on April 4, in the 18th district. David enlisted at the very start of the Second World War with the Foreign Voluntary Infantry Regiment (regimental number 841). He was subsequently placed under house arrest in Lacaune, in the Tarn department of France[17]. Between 1942 and 1944, almost 650 Jews were captured in Lacaune. The first round-up took place on August 26, 1942, and 90 Jews, including 22 children, were deported. After the second roundup, on February 20, 1943, 29 men were taken to the Gurs camp, transferred to Drancy, and then deported to Maidanek on Convoys 50 and 51 on March 4 and 6, 1943. None of them survived. David was deported on Convoy 51. His name is inscribed on the war memorial in Lacaune. His wife had been deported previously, from Pithiviers to Auschwitz, on Convoy 35 on September 21, 1942.

The memorial in Lacaune – Wikipedia

- Lazare Pelta, who was born in 1901 in Wieluń, married Marie Schwartz on May 22 1930[18] in the 15th district of Paris. As far as we are aware, they had no children. Both worked in the fur trade. We do not know for sure, but it was probably during the “roundup of notables” on December 12, 1941, that Lazare was arrested and taken to the Royallieu camp near Compiègne, in the Oise department of France, where he died on February 16, 1942. His name is inscribed on the communal grave in the South Cemetery in Compiègne. 137 internees from the camp were buried there after being tortured or shot. Marie Schwartz arrived in Drancy on May 13, 1944, and was deported to Auschwitz on Convoy 74 on May 20.

The communal grave in the South cemetery in Compiègne – our own photo

Marie was the only one of the twenty-two family members who survived and made it back from the camps!

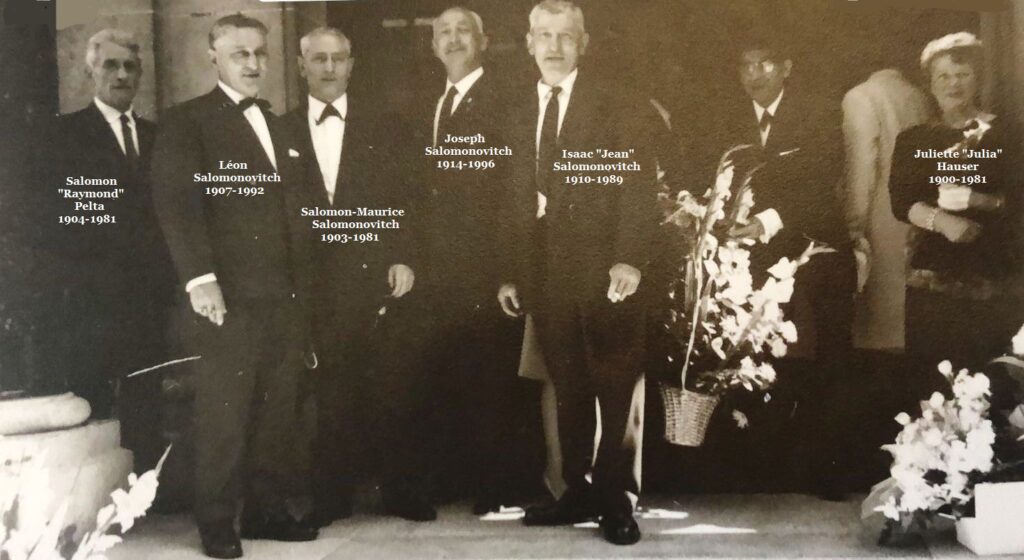

Their wedding photo, dating from 1930, puts a face to the name of many of the family members mentioned in this biography.

Lazare Pelta and Marie Schwartz wedding – Paris, May 22, 1930 – Family photo

- Salomon “Raymond” Pelta [19], who was born in 1904 in Osjaków, married Adèle Herschcelikovitch, his brother Idel’s wife’s sister, in a religious ceremony held at the Tournelles synagogue in Paris on June 22, 1930. He too was a furrier, first on rue Boutry in Paris and then in Montreuil. He was a 2nd class private in the 621st regiment of the French army. He was taken prisoner of war in Germany in 1941 and incarcerated in Stalag XVII B. He subsequently returned to France and was naturalized as a French citizen by decree, which was published in the French official gazette on February 22, 1947.

Salomon and Adèleat at their wedding in 1930 – Family photo

He died at 9, rue Carnot in Montreuil in 1981; making him the only member of the family who was not rounded up and deported. He kept in touch with the rest of the Salomonovitch family after the war.

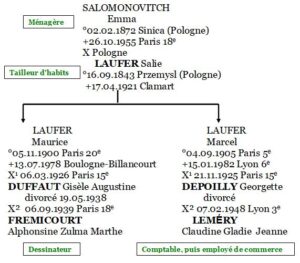

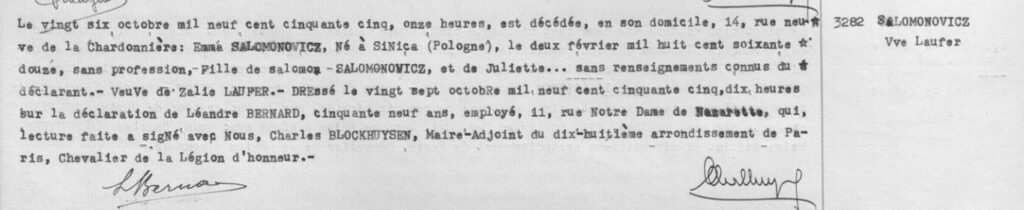

III – EMMA (1872-1955) AND THE LAUFER FAMILY

We had numerous questions about this family when we first made contact with the present-day Salomonovitch descendants: they all mentioned the “Laufer” family and had some photos of them, including a particularly precious one annotated by the late “elders” of the family, stating that Marcel Laufer’s mother was Abraham’s sister. We had found nothing in the registry office, and had even come to believe that there was no link between the Salomonovitch and Laufer families until we spoke with the family members themselves.

After a very long search, we finally managed to solve the enigma: an Emma Salomonovitch did indeed marry a Laufer and went on to have two sons: Maurice, in 1900 in the 18th district of Paris, and Marcel, in 1905, in the 5th district.

Despite an error in the ten-year index (but fortunately not in the registers), we finally found a record of Emma’s death in Paris in 1955.

Emma Laufer, née Salomonovitch’s death certificate – 18th district of Paris, 1955

We can see that the person who made the declaration was not very sure of themself: Emma’s mother was said to have been called Juliette (although admittedly Salomon Salomonovitch’s (now Salomonowicz’s) wife never seemed to have the same first name)! What is even more curious is that the birth certificate is quite specific, and states that she was born in Sinica, a Polish township nearly 200 miles from where her siblings were born. Then again, anything is possible: one pogrom was all it took to prompt some Jewish families flee their homes. When she died in 1955, Emma’s husband Salie, who was 29 years older than her, had been dead for 34 years! We finally found them in the burial registers: he was buried in the Bagneux cemetery[20], and she in a plot that her son Maurice bought in the Pantin cemetery[21], both on the outskirts of Paris.

As we have already mentioned, her son’s birth certificate, issued at the Tenon hospital in the 20th district of Paris in 1900, was the very first birth certificate issued in Paris for this Polish family. Emma Salomonovitch was therefore definitely living in Paris by then. We know where they lived from the various records: the couple were living at 71, rue Saint-Jacques in the 5th district when their two children were born. When Salie died in Clamart in 1921, he was living at 73, avenue Victor in Clamart, a suburb south west of Paris, although we do not know why. In 1925 and 1926, Emma was living at 10, passage Ribet in the 15th district [22] and in 1939, when her son got married, until her death in 1955, she lived at 14, rue Neuve de la Chardonnière in the 18th district.

Photo 1: Seated: Emma Laufer, née Salomonovitch. The young man behind her could be Ferdinand Salomonovitch – Family photo

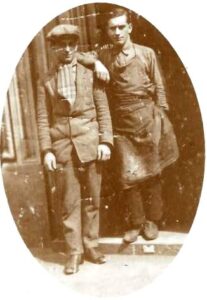

Photo 2: Ferdinand Salomonovitch (standing) and Marcel Laufer (seated) – Family photo

The present family members remember a physician by the name of Laufer who treated some members of the family: might he have been Maurice and Marcel’s brother?

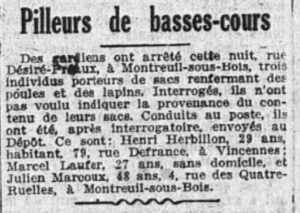

Lastly, an amusing anecdote about this branch of the family: a short article found in the French newspaper L’Intransigeant dated August 24, 1932, relating to a chicken-stealing racket! We have no proof that the Marcel Laufer involved was “our” Marcel, but the age matches!

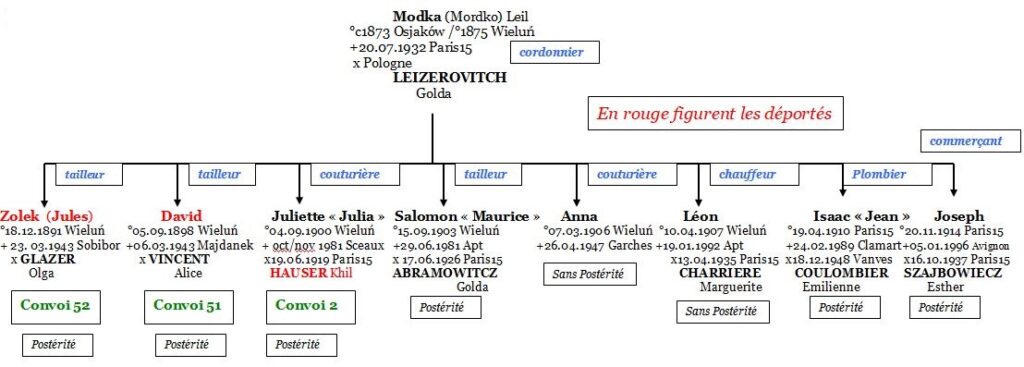

IV – MORDKA (c1873-1932) AND HIS DESCENDANTS

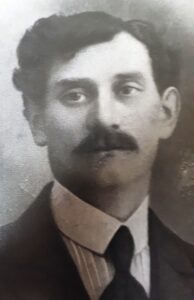

Mordka – Family photo

Although Mordka was Salomon’s first son, he was not the first to arrive in France (his last son Léon was born in Poland in 1907). We can track his numerous changes of address in Paris [23]: 27, rue Dupleix and 3, Place Dupleix in 1910, then 21, rue de l’Eglise at the start of the First World War in 1914 and then 70, rue de Lourmel in 1919 [24]. In 1926, he moved permanently to 10, impasse Ribet in the 15th district, where he died in 1932 [25]. In common with many other members of his family, he was a shoemaker. He was buried on July 31, 1932 in the same vault as his sister Khoudes, in the Bagneux cemetery.

Mordka, his wife Golda and their son Salomon Maurice – Family photo

His wife, Golda Leizerovitch, was also buried in the same vault a year later, having spent a year in a retirement home on rue Houdan in Sceaux, in the Hauts-de-Seine department of France. The couple had eight children:

The first six were born in Wieluń:

- Zolec (Jules), born December 28, 1891,

- David, born September 5, 1898,

- Juliette, born September 4, 1900,

- Salomon Maurice, born September 15, 1903,

- Anna, born March 7, 1906,

- Léon, born April 10, 1907.

After they arrived in France, they had another two children in the 15th district of Paris:

- Isaac, also known as Jean, born April 19, 1910,

- Joseph, born November 20, 1914.

Page from the French newspaper “Le Matin”, 16 mai 1914

Amid a story fraught with grief and tragedy, a brief anecdote that might raise a smile (although no doubt not for the unfortunate woman involved): on May 16, 1914, a short legal column appeared in the daily paper Le Matin, chronicling an unusual court case between a Mrs. Salomonovitch and a physician, Dr. Laurent de Belloc. Blessed with “well-developed body hair growth”, she had decided, “out of a justifiable sense of vanity, to seek the services of a doctor who treated her with X-rays, causing radiodermatitis and permanent ulcerations on her legs”. She claimed that the doctor had not sufficiently warned her about the risks involved, and that he should have confined himself “to the removal of the deformity known as ‘sapper’s beard’ in women”, he was ordered to pay eighteen thousand francs in damages.

This bears witness to a time when the Curies’ discoveries were being tested for the first time! We have no idea which “Mrs. Salomonovitch” this refers to, given that we found no woman in the family who married in or around 1914.

Moving on, we shall now attempt to reconstruct the lives of Mordka and Golda’s eight children:

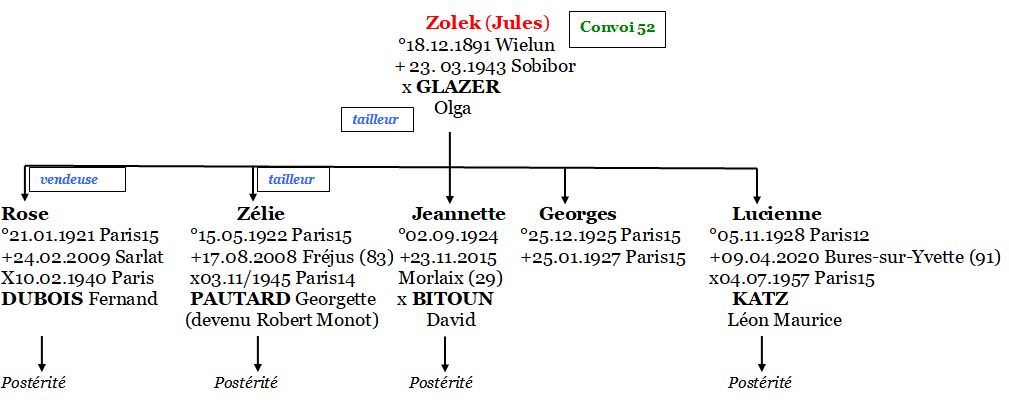

1. Jules (1891-1943) and David (1898-1943), the oldest two boys

When war broke out in 1914, all the Salomonovitch family members from this branch of the family were in France. Of Mordka’s eight children, only the eldest, Zolec, better known as Jules[26], who was born in 1891, was old enough to fight. As a Polish citizen, however, he could not join the French army.

At the age of 19, Jules therefore joined the French Foreign Legion. He fought in the war, and we know from a later record that he was awarded the French War Cross. In 1919-1920, he fought against the Bolsheviks in Poland. It was there that he met his future wife, Ukrainian-born Olga Glazer. They probably got married in Poland, but their five children were all born in France, in the 15th district of Paris: Rose [27] (1921), Zélie (1924) [28], Jeannette (1924), Georges (1925) [29] and Lucienne (1928).

Jules was a tailor and, according to the 1926, 1931 and 1936 censuses, lived at 81, rue du Théâtre in the 15th district of Paris.

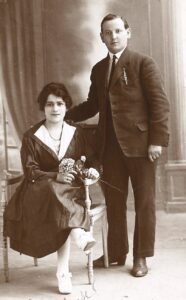

Jules and Olga Glazer – Family photo

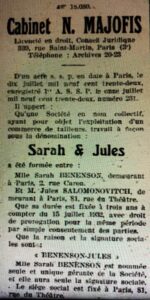

In 1936, the family moved in together: Jules, his wife and daughters lived in one apartment, and his brother Salomon Maurice, his wife and their son moved in to the adjoining apartment, as did their unmarried sister Anna, who was born in 1906. On July 11, 1932, Jules and a woman named Sarah Benenson set up a company called “Sarah et Jules” and operated a tailoring/made-to-order business based at Jules’ home address, at 81, rue du Théâtre. On June 26, 1933, however, according to an article in Le Matin, the company was declared bankrupt.

Photo 1: French commercial archives, July 20, 1932 newspaper announcement

Photo 2: 81, rue du Théâtre in the 15th district: The Abrahamowicz family lived in this building (on the first and 4th floor) after the war, as did some other family members. Behind it was another building overlooking the courtyard, where Jules and his family lived, as did Salomon Maurice and his family. It was also the head office of Jules’s company. Photo: Google Maps

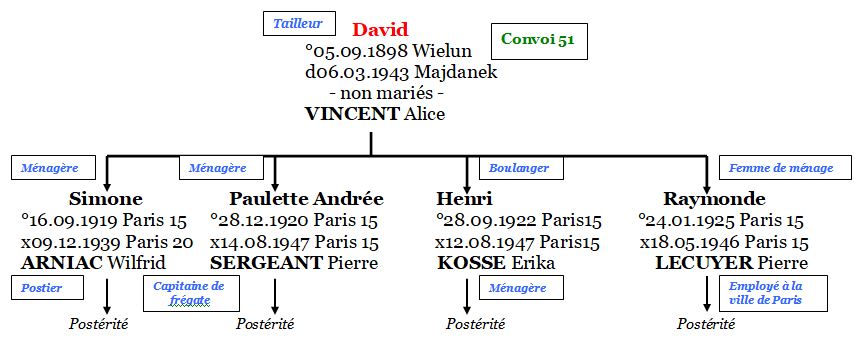

His brother David, who was born on September 05, 1898 in Wieluń and also worked as a tailor, turned 18 and thus became old enough to fight at the front in 1916. He was awarded the French War Cross. We were able to retrace his career from registry office and census records for the 15th district of Paris.

In June 1910, Alice Albertine Amanda Vincent married an accountant, Armand Maginaut, in the 15th district of Paris. They had a daughter, Odette, in 1913, but he was killed on the front in the Meuse department in February 1916. The young widow was left to raise her three-year-old daughter alone. She soon began a relationship with David Salomonovitch, and although they never married, she had four more children with him: Simone (1919), Paulette Andrée (1920), Henri (1922) and Raymonde (1925) [30].

Alice Vincent – Family photo

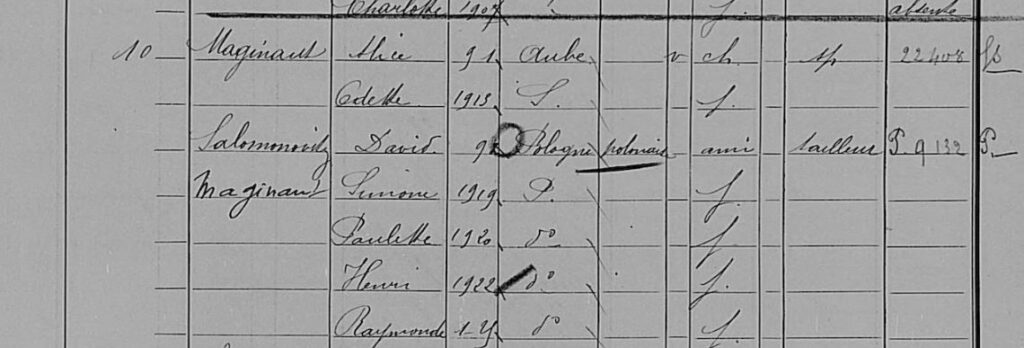

David is listed in the 1926 census as living with Alice Vincent, at 7, rue Léontine-Prolongée in the 15th district. Interestingly, he is listed as a “friend”, and the four children are listed under the surname Maginaut, even though Armand had died three years before the first child was born!

This is probably a photo of David Salomonovitch (born in 1898) – Family photo

We do not know where the family was living at the time of the 1931 census, but we catch up with them again in the 1936 census, by which time they were living at 10, Impasse Ribet in the 15th district. This suggests that David had taken over the apartment from his father, who died there four years earlier.

7, Passage Léontine-Prolongée – Photo: Google Maps

In 1939, when their daughter Simone got married, David and Alice were living at 84, rue Lecourbe in the 15th district. They never married, as we said above, and her death certificate, which was issued in the 13th district of Paris in 1970, still says that she was the widow of Armand Maginaut!

1926 census listing for 7, Passage Léontine-Prolongée

2. David’s descendants: unravelling a mystery about a record from the Shoah Memorial

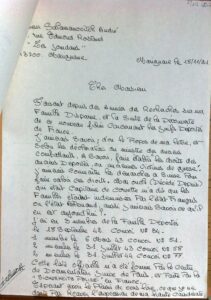

Among the documents in the file on David Salomonovitch provided by the Convoy 77 team there was a letter, dated 1991, from a certain André Salomonovitch in Marignane, asking for information about some of his family members who were deported:

We did not pay much attention to it initially: we just assumed it was from Mordka’s grandson André, who was born in 1941. However, when we got in touch with André’s widow, she assured us that her husband had not written the letter, and that they had never lived in Marignane, which is near Marseille, on the south coast of France.

We were baffled by this revelation: in that case, who on earth was this other André? None of the present-day family members could help us; they too were puzzled. We did some more digging, of course, but there is no longer anyone by the name of Salomonovitch in Marignane to point us in the right direction.

The letter did, however, include one important detail: André mentioned that one of his uncles, who was already dead when the letter was written, had been a “captain of a corvette” (a small warship). This was not much of a clue, given that the said uncle might not even have been a Salomonovitch at all, but it was still worth looking into. It was our comprehensive study of the family that eventually enabled us to solve the “mystery”: David (born 1898) had four children with his partner, Alice Vincent. Three of them were women, but were married, so of course their children would not have the surname Salomonovitch.

In 1947, Paulette, who was born in 1920, married a man called Pierre Omer Sergeant, and it just so happens that he was in fact … the captain of a corvette! Born in 1921 in Millencourt, in the Somme department, he was still a student when, in June 1940, he joined the French navy. At the end of the war, he stayed on in the navy, served in the Indo-Chinese campaigns, and was promoted in 1966 to be the captain of a frigate. He died in Rouen, on the north coast of France [31] in 1988, three years before André wrote the letter. The mysterious André therefore had to be one of Paulette’s brothers’ sons, so her nephew. And, although David had four children, only one of them was a boy: Henri, who was born in 1922 and married a German woman from Berlin, Erika Anneliese Kosse, in 1947.

Pierre Sergeant

Source: compagnonshavrais.jimdofree.com

If our analysis turns out to be correct, André would have been born in or after late 1947. Perhaps one day he will read this biography, in which case we hope he will find out a little more about his family.

In the meantime, let us return to the story of what became of Jules and David.

3. The war: house arrests and the deportation of Jules and David

When the Second World War broke out, Jules and David got caught up in a downward spiral that culminated in them being deported to the camps. Although we have a lot of information about this period, we must admit that some of it is incomplete, so we are still unsure about exactly what happened because in some cases, the records contain contradictory information.

The oldest living members of the Salomonovitch family were too young at the time to know very much about what happened. We shall therefore back up documentary evidence with their suppositions, which are probably, albeit not definitely, correct.

Jules Salomonovitch – Shoah Memorial

We shall begin by discussing our two eldest sons, Jules and David, who followed a broadly similar route.

We know very little about Jules and David’s lives at the start of the war, other than that Jules and his wife separated in the early 1940s. We do have one record, dated April 25, 1940, which suggests that David wanted to enlist in the French army: he asked for his Polish identity card to be exchanged for a card saying “undetermined nationality”, which was required in order to enlist. He obtained the card from the Polish consulate, but after the Armistice he was no longer eligible to join the French army.

Letter from the General Security Service dated April 25, 1940 – French Police Archives, ref. 1999 40 446/3

We do not know when or in what circumstances, but at some point, the two brothers crossed the demarcation line into the “free zone” in the southern, unoccupied part of France. The next trace we found them was when they were placed under house arrest in the Cantal department.

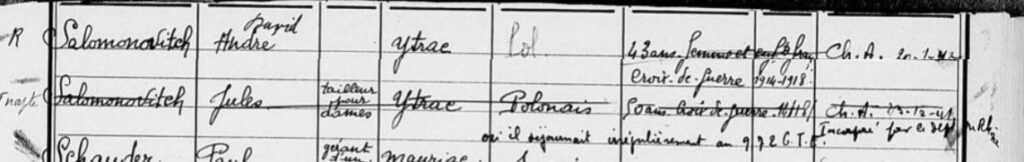

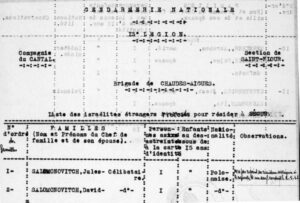

Cantal departmental archives – ref. 9NUM7

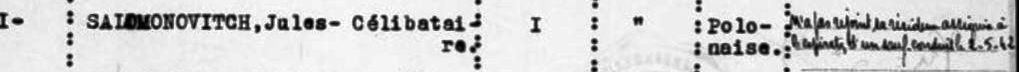

This record list both of their names and includes the following information:

- Jules, who was described as a “ladies’ tailor” and “unfit for work” (no doubt meaning unsuited to hard, industrial work), was interned by the Rhône department authorities while he was“ staying at 972 GTE”. The GTEs were groups of foreign workers, established under a law passed on September 27, 1940. Their purpose was to reduce unemployment by excluding Spanish Republicans, prisoners of the Reich (before the Armistice), and Jews, who were “surplus to requirements for the national economy”. Run by the Ministry of Industrial Production and Labor and managed by a reserve officer, the GTEs each comprised some 250 men, who were paid a pittance and were usually assigned to back-breaking jobs, which varied widely from one place to another. In 1941, there were five GTEs in France, one of which was based in Lyon, in the Rhone department. The GTE 972 group, made up of Polish workers, was stationed at the Chapoly fort in Saint-Genis-les-Ollieres. This particular GTE was more arduous than most since discipline was strict and it even had its own jail. What follows is our attempt to piece together a possible storyline, even though we have few details to go on. Jules crossed the demarcation line in 1941. Having been arrested during a roundup (perhaps in Lyon?), he was assigned to a GTE. Since he was unable to do the hard work required, but had a means of supporting himself, he was eventually placed under house arrest on December 23, 1941, first in Ytrac and then in Chaudes-Aigues, both in the Cantal department of France.

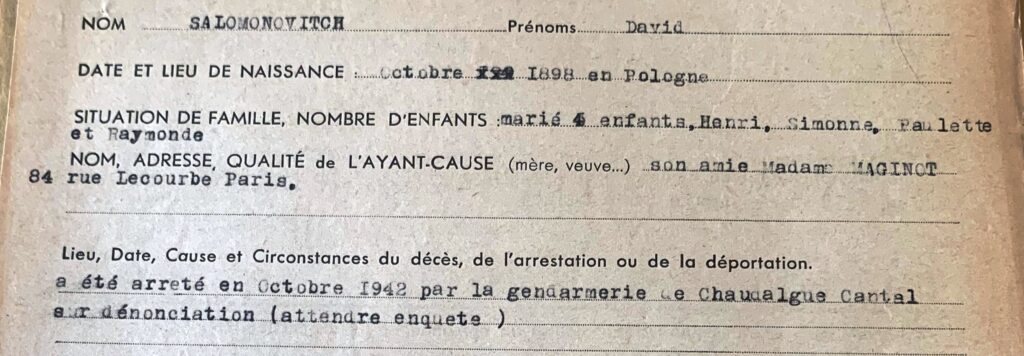

- As regards David, we have a file dated 1947 which contains various documents gathered together by his partner, Alice David, and then by his eldest daughter, Simone, in order to have him recognized as having been a member of the FFI (French Forces of the Interior, part of the Resistance) [32]: Some of the details in the file are incorrect, however: he was born in either 1896 or 1898, depending on the record, and may or may not have been married. He is said to have crossed the demarcation line in July 1940 [33] and to have set up home in Chaudes-Aigues, but then another record contradicts this, stating that he spent only a short time there and then moved to somewhere near Aurillac, also in the Cantal department, but we found no record of him ever having spent time there.

Cantal departmental archives – ref. 9NUM7

The Victims of Contemporary Conflicts Archives Division of the Ministry of Defense Historical Service, in Caen, Normandy, holds an application for Jules to be recognized as having been a political deportee. One record says that on January 20, 1942, he was put under house arrest in Rouget-Pers, which at that time was in the municipality of Saint-Mamet-la-Salvetat, also in the Cantal department, supposedly with his wife and a child [34]. There is then a decree dated January 29 of the same year [35] instructing him to move back to Chaudes-Aigues within the next two weeks [36]. A slightly later record, which unfortunately is not dated, states that both Jules and David were in Chaudes-Aigues at the same time, as part of a group of 69 Jews, and both of them were single [37]! And then, according to a record from the French military archives in Vincennes, [38] the Chaudes-Aigues gendarmerie (military police) arrested him in October 1942 after someone had turned him in.

French Military archives in Vincennes – ref. 16P 532 893

While the internment and transit camps in the southern zone (Gurs, Rivesaltes, Les Milles, etc.) are well documented and have been widely researched, this does not seem to be the case for a system that impacted a large number of foreign Jews: house arrest. We touched on this in the first part of this biography, since David Pelta was placed under house arrest in Lacaune, in the Tarn department of France [39]. There were thirty of so internment facilities, known as “Assigned Residence Centers”, in the southern zone. They were set up under the terms of a French decree dated October 4, 1940, which stated that “foreign nationals of the Jewish race may, at any time, be assigned compulsory residence by the Prefect of the department in which they live”. These centers began to spring up at the end of 1941 [40] and their numbers peaked in 1943.

The municipalities chosen to house the Jews in the Free Zone region all shared similar characteristics: a small, remote town [41] in a rural setting, with a military police station and suitable accommodation. Small spa towns, where tourism had all but dried up during the war, fitted the bill perfectly, for example. People who had the means to support themselves tended to be placed under house arrest [42], while the rest were interned in camps. This was seen as a more cost-effective way for the Vichy government to segregate Jews without having to intern them. In theory, women and children under the age of fifteen and people over sixty were not eligible. The living conditions of the people kept under house arrest depended on the price of “board and lodging” that they could afford to pay.

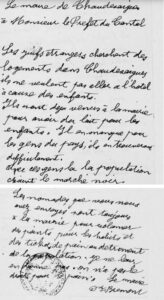

Located close to the town of Saint-Flour, Chaudes-Aigues met all the essential criteria: a small rural spa resort well away from major urban population centers. A municipal order dated June 01, 1942 decreed that “Jews in compulsory residence in Chaudes-Aigues will only be allowed access to retail stores selling food products from 10:30 a.m. to midday and from 4:00 p.m. to 6:00 p.m., the remainder of the day being strictly reserved for the French population of Chaudes-Aigues”. To begin with, the municipalities and their local residents were opposed to this sudden influx of Jews, which they saw as an invasion: not only was it the first time many rural communities had come into contact with Jewish people, but they also saw them as lazy (although in reality they had lost their businesses or been fired from their jobs). This fueled anti-Semitism: the Jews were seen as “parasites”, who made no effort to earn a living! Another common accusation was that they traded on the black market to buy food.

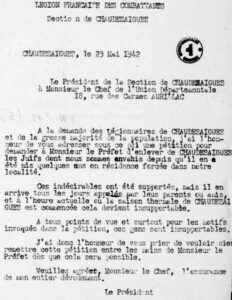

Letter from Mr. Brémont, the mayor of Chaudesaigues, and a petition signed by all the local French Legion of Veterans members, dated May 16, 1942. These not only reflect the prevailing anti-Semitism, but also total ignorance – whether intentional or not – of the dreadful plight of the people under house arrest. Source: Cantal departmental archives, ref. 9NUM7

The demands were seconded, on May 23, 1942, by the French Legion of Veterans, a Vichy movement, which clearly revealed their political and ideological leanings.

Cantal departmental archives – ref. 9NUM7

Despite all this, little by little, the local population began to befriend the people sent to live in their area. Initially, this was purely pragmatic: for private individuals who housed Jews, as well as owners and managers of hotels and spa complexes, who were hit by the downturn in tourism during the war, it offered an opportunity to make a small profit. A mutually beneficial barter system emerged: a large number of people under house arrest were craftsmen (shoemakers, tailors, etc.), so they worked in exchange for agricultural produce. Although house arrest was seen as less harsh than internment in camps, it only provided short-term protection: not only were people still rounded up, as happened to David Pelta, but as soon as their funds were exhausted, they were sent to camps in France, or even deported to Poland.

Was David Salomonovitch involved in the Resistance? A record in the French Forces of the Interior file[43] suggests that he belonged to a resistance movement affiliated to the eighth Lyon district. However, the family’s 1947 application to have him recognized as having been an FFI member was rejected by the validation commission, which, after examining his case file, deemed that there was insufficient evidence to support their claim. Another record in the file says that he was interned on March 1, 1943, but provides no further details.

For Jules, the situation is less clear: as we mentioned earlier, he was placed under house arrest in the Cantal department in December 1941, first in Ytrac and then in Chaudes-Aigues. According to a report in the Cantal departmental archives, he was granted a pass to go out on May 2, 1942, but did not come back!

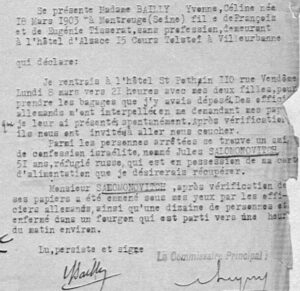

The next trace of him is a few months later, but we have no idea what he did or where he stayed in the meantime. On March 13, 1943, a report from the chief superintendent of police for the greater Lyon area states that Jules had been arrested. The story is not entirely clear: a Mrs. Bailly, who had her two daughters with her, was on her way back to her hotel at 110, rue de Vendôme [44] to pick up some luggage when she witnessed the arrest of a dozen or so people, including Jules. She added, however, that he had her food ration card, and that she wanted it back! The story within the family is that she must have been his mistress.

Official report from the Lyon Regional Criminal Investigation Department dated March 13 1943. Rhône departmental archives, ref. 3335W30, 3335W1

We have no idea why Jules was in Lyon, or whether or not Mrs. Bailly got back her ration card. For Jules, however, who had never declared to the Vichy authorities that he was Jewish, and who was apparently carrying false identity papers, this was the start of a rapid downward spiral. He was arrested on March 8 in Lyon, held in Montluc prison for ten days and then transferred to Drancy camp, even though he was suffering from typhoid. He was deported on Convoy 52 on March 23, 1943. That day, at 9:42 a.m., 994 Jews, carrying just a few provisions and a small suitcase, were loaded onto buses and taken to the Bourget-Drancy railway station. They were deported to the Sobibor extermination camp. It is assumed that Jules was murdered in the gas chambers as soon as he arrived.

David did not fare much better: when two Luftwaffe officers were killed in Paris on February 13, 1943, the Germans retaliated by arresting and deporting 2,000 Jews. Most of them were arrested in the Free zone in the southern part of France, and foreign Jews in particular were targeted. Most of them were taken to the Gurs camp to begin with, then transferred to Drancy, where they arrived on March 4. Two days later, at 8.55 a.m., Convoy 51 left the Bourget-Drancy station with 1,000 Jews on board, including David, bound for the Majdanek camp. By 1945, only five people from this transport had survived.

There is a memorial at the La Mouche Jewish cemetery in the Gerland district of Lyon dedicated to the deported Jews who passed through the Rhone department, in particular the ones who were held in Montluc. The names of four members of the Salomonovitch family are inscribed on it, together with their birth years and convoy numbers. They include Jules and David, whose itinerary we have attempted to retrace above, as well as the other David (born in 1909), who we shall cover in the next section, and Maurice (see section VI), both of whom left were deported on Convoy 77.

The La Mouche Jewish cemetery in Lyon

Photo: Geneawiki

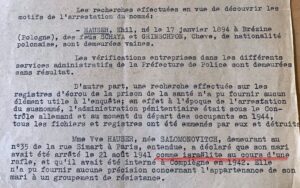

4. Juliette and Khil Hauser

Mordka and Golda’s third child, Juliette [45] and [46], was born on September 4, 1900 [47] in Wieluń. On June 19, 1919, she married Khil Hauser from Brzeziny, a village east of Łódź, in Poland, in the 15th district of Paris. At that time, she was a seamstress and was living with her parents at 70, Rue Lourmel, while he was a tailor. They went on to have one son: Maurice. In 1926, the family was living at 19, rue Boinod in the 18th district [48].

Photo 1: “Julia” and Khil Hauser

Photo 2: Maurice Hauser, Julia and Khil’s only son

Family photo

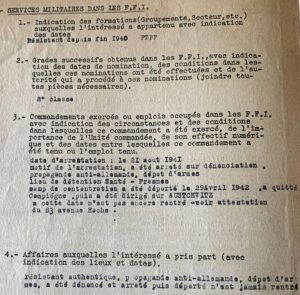

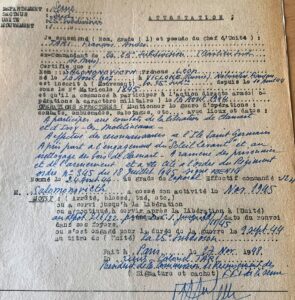

We found a dossier on Khil Hauser in the French Defense Historical Service Archives in Vincennes [49]. The file, which is in two parts, is fascinating. It shows how difficult it was to have someone recognized as having been active in the French Forces of the Interior, i.e. the Resistance: firstly, from an investigation that began in 1946, we see that in 1939 he served in the 2nd Foreign Infantry Regiment, and then in November 1940, he joined the FTPF (Francs-Tireurs et Partisans, the Communist Resistance). Then, on August 21, 1941, when he was a second-class soldier in the FFI, he was arrested after having been reported for taking part in an anti-German propaganda operation and for storing firearms. He was first interned in Drancy, in then La Santé, Fresnes and Compiègne, and as finally deported to Auschwitz on Convoy 2 on April 29, 1942. It was confirmed that he had been an active member of the FFI.

Khil Hauser

Family photo

French Defense Historical Service archives in Vincennes

FFI file on Khil Hauser, ref. 16P287144

In 1951, however, his case was reviewed. This time, it was decided that there was insufficient proof that he had been active in the Resistance. The report stated that the prison registers from La Santé, which could have provided additional information, had been destroyed by the occupying forces. In addition, his wife “declared that her husband had been arrested during a roundup on August 21, 1941, because he was a Jew, that he had been interned at Compiègne in 1942, and that she was unable to provide any details about her husband’s membership of a resistance group”. As a result, Khil Hauser’s status as an ex-FFI member was revoked.

French Defense Historical Service archives in Vincennes

FFI file on Khil Hauser, ref. 16P287144

Either way, Khil Hauser was deported from Compiègne to Auschwitz on Convoy 2. He never came home.

5. Salomon Maurice (1903-1981)

Salomon Maurice was born on September 15, 1903 in Wieluń. He was still living with his parents at 10 Impasse Ribet when, on June 17, 1926, in the 15th district of Paris, he married his cousin Golda Abrahamowicz, who was Sura Salomonovitch’s daughter. Their witnesses were Alice Maginaut, the girlfriend of David Salomonovitch, the groom’s brother, and Juliette Hauser, his sister.

In 1932, when he declared his father’s death in the 15th district of Paris, he was living at 12, re Buté in Bobigny in the Seine-Saint-Denis department and was working as a cobbler [50]. A year later, when he declared his mother’s death in Sceaux, he was living at 33, rue Robert Lindet in the 15th district. The couple had two children: Félix, who was born in 1928 and died the following year in the 15th district [51], and Henri, who was born on November 22, 1931 in La Courneuve in the Seine-Saint-Denis department and who died on May 4, 2024, while we drafting this biography. He worked for the French car manufacturer, Citroën, before the war.

During the war, he and his wife kept a low profile and continued to live at 81, rue du Théâtre in Paris, where, according to the 1936 census and as we mentioned earlier, some of the other family members also lived. They sent their son Henri to stay with a farming family in the Auvergne region of France during the war [52]. One of their neighbors, a police officer by the name of Scabini, who was originally from Corsica [53], warned them several times that roundups or police raids were about to take place. This was what enabled them, unlike so many other members of the family, to survive.

Long after the war, Salomon-Maurice and his brother Léon built two terraced houses in Apt, in the Vaucleuse department of France, where their brother Joseph also lived (see below). He lived in Apt until his death, after which his body was taken back to Paris and buried in the family vault in the Bagneux cemetery.

6. Anna (1906-1947)

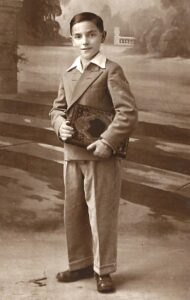

Anna’s bar-mitzvah photo, 1918

Family photo

We have very little information about Anna, who was Mordka and Golda’s fifth child. She was born in Wieluń on March 7, 1906. She was a delicate woman, never married, had no children, and died relatively young at the Garches hospital in the Hauts-de-Seine department on April 26, 1947. Listed in the 1926 census as a dressmaker living at 10, Passage Ribet in the 15th district, by 1931 she was working as a saleswoman for Maison Rabaux in the 19th district, and in the 1936 census, she declared that she was a painter!

Anna is also buried in the Bagneux cemetery, but not in the family vault [54].

7. Léon (1907-1992)

Léon, Mordka and Golda’s sixth child, was born on April 10, 1907 in Wieluń. According to the 1926 census, he was then living with his parents at 10, Passage Ribet and working as a driver. When he married Marguerite Charrière, a telephone operator, on April 13, 1935 at the town hall in the 15th district of Paris, he was a warehouseman and lived at 27, rue Robert Lindet. His sister Juliette was one of the witnesses at the wedding. Léon and his wife had no children.

His FFI accreditation dossier in the French Defense Historical Service archives in Vincennes [55] provides some information about what happened to him during the war: he enlisted in 1939, but for some reason was never called up, so went into hiding in Clamart in the Hauts-de-Seine department after the armistice was signed, and then crossed into the Free Zone. He was arrested and interned in the Malaval camp in Marseille, on the south coast of France, but managed to escape. On August 10, 1944, he joined the Resistance [56] and was active in the FFI in the Seine department [57] from August 18 – 25, 1944. He took part in the liberation of Clamart and Issy-les-Moulineaux, was involved in reconnaissance operations at Ile-Saint-Germain (in Issy-les-Moulineaux), took part in the “Soleil levant” (“Rising Sun”) operation [58] and in the sweep of the woods around Clamart, from which he brought back prisoners and weapons, for which he was commended in the regimental roll of honor. On August 24, he was appointed corporal.

French Defense Historical Service archives in Vincennes

FFI file on Léon Salomonovitch, ref. 19 P 532 895

He was officially recognized as a member of the FFI and demobilized in November 1945. He later became a salesman. When he retired, he and his brother Salomon Maurice both built houses near their brother Joseph, in Apt. Léon and his wife are buried in the Saint-Saturnin cemetery in Apt.

8. Isaac, known as “Jean” (1910-1989)

Of all the siblings, Isaac, who went by the name of Jean[59], was the one who lived furthest from the rest of the family: as a result, we know very little about him. Born on April 19, 1910 in the 15th district of Paris, he worked as a mechanic and then as a plumber. He became a corporal during the war, was taken prisoner and held in a German Stalag. On December 18, 1948, in Vanves, in the Hauts-de-Seine department, he married Emilienne Elisa Coulombier. They went on to have just one daughter, Jeannette.

He died in Clamart on February 24, 1989 and is buried in the Montrouge cemetery in Paris.

9. Joseph (1914-1996)

Mordka and Golda’s last child, Joseph, was born on September 20, 1914 in the 15th district of Paris. It was there, on October 16, 1937 that he married Esther Szajbowiecz. He was a driver at the time and lived at 81, rue du Théâtre. She lived at 27, rue Robert Lindet. His brother David, who was also a driver, was one of the witnesses.

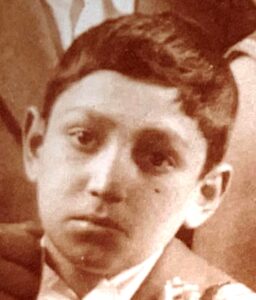

In 1941, he made the headlines: he and several associates were operating a gold-dollar racket in the Bourse district of Paris. Unfortunately for them, they approached four police inspectors and offered them a deal!

Cutting 1: from the Paris-Soir newspaper of February 24, 1941

Cutting: from Le Matin newspaper, also of February 24, 1941

They were caught after a chase through the Saint-Denis subway station, but we do not know what happened to them in the end.

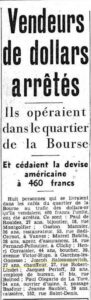

We do know that shortly afterwards, Joseph made his way to Toulouse, in the Free Zone, where he stayed with a Catholic family. When the Germans took over the Free Zone and invaded Toulouse, he felt that it was too risky, so he and his family left the city. We next catch up with them in the Vacleuse department, where Joseph joined a Resistance group [60]: he served in the Free French Forces (FFI) from February 01, 1943 to August 26, 1944, and was promoted to the rank of sergeant-in-chief. He was commended in the Regimental Order [61] and praised for his role in a number of operations, including picking-up aircraft drops, being the driver in the unit that supplied weapons to the various networks in the Vaucluse, even where the German army was patrolling nearby, and for his daring and skill when the Resistance took over the town of Apt between August 20 and 22, 1944.

His FFI file [62] provides further details of his work: assigned to the local transport unit, between March and December 1942 he was the driver, day and night, for the Resistance group in Apt. In February and March 1943, he worked as a recruiter for the regional Resistance. In November and December 1943, he provided transport for the Resistance group led by the communist Alphonse Dumay, alias Commandant Lazare. In January and February 1944, he did the same for the Céreste group (in which he may have met the well-known poet René Char, who was a member at the time). In March 1944, he was involved in transporting firearms to Lagarde d’Apt. Lastly, in August 1944, he took part in the liberation of Apt, and was the driver for Commandant Henry of the Inter-Allied General Staff.

Commendation of the Regimental Order,

French Defense Historical Service archives in Vincennes, FFI file 16 P 532 894

Joseph and Esther had two sons: the first was Léon, born in 1931, who was sent to stay in Clamart with his aunt, Marguerite Charrière during the war. The second was André, who was born in Toulouse at the height of the war on October 15, 1941. Esther took supplies to Joseph when he was working with the Resistance, carrying their young son in a little cart hitched to her bicycle! After the war, the family decided to stay in the area for good: Joseph sold sheets on the markets and went on to open a clothing store. In 1965, André married his cousin, Estera [63], who is now the eldest living member of the family, and with whom we made contact. She kindly shared many of her memories and photos, some of which we have used in this biography.

André and Estera’s wedding, 1965 – Family photo

Joseph and his wife were both buried in the Jewish cemetery in Avignon, in the Vaucleuse department of France, as was their son André in 2005.

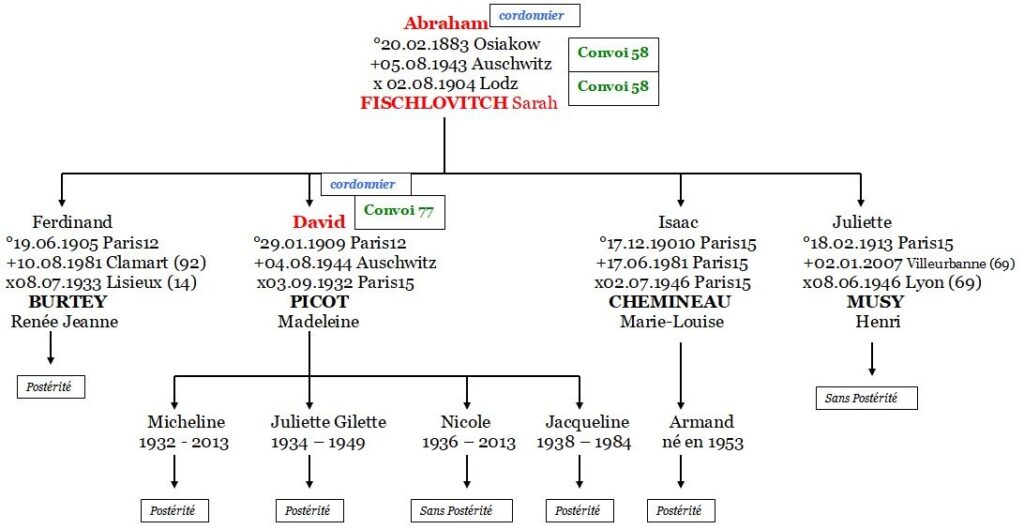

V – ABRAHAM (1883-1943) AND HIS DESCENDANTS: David Salomonovitch’s branch

The Convoy 77 project team originally asked us to focus on David and write his biography; we are therefore going to discuss his parents’ descendants as they relate to him.

1. Abraham and Sarah: his parents

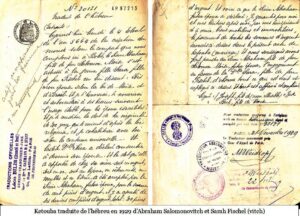

Abraham was born in Osjaków on February 20, 1883 [64]. He married Sarah Fischlovitch [65], who was born in Ozorków on December 1879, on August 2, 1904 in Lódź (Poland).

Abraham arrived in France in 1905, and from his application to be naturalized as a French citizen in 1930, we discovered that they lived at 94, rue Mouffetard for 2 years, then at 11, rue Beaubourg [66], again for about 2 years, and then at 9, Passage Gustave Lepeu (off rue des Boulets) for a year. In April 1910, they moved permanently to 81, rue de Lourmel in the 15th district of Paris [67].

He and his wife had four children: Ferdinand in 1905, David in 1909, Isaac in 1910, and Juliette, the only girl, in 1913.

In 1925, Abraham registered as a shoemaker/cobbler.

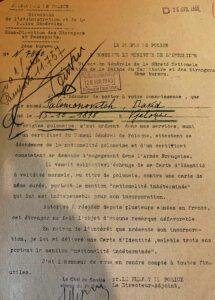

In 1929, he applied for French nationality. The police department issued a report on the family on November 12, 1929, which included a great deal of information, in particular on the family’s financial situation: it stated that he earned between 35 and 40 francs a day, and that he had not registered his store at 18, rue Lauriston, which he rented for 150 francs a month. The family paid a 700 francs a month rent for their apartment on rue Lourmel. As for his children, Ferdinand was a mechanic and earned 40 francs a day; Isaac worked with his father and earned 20 francs a day, while Juliette earned 450 francs a month as a hosiery saleswoman on rue Tiquetonne[68].

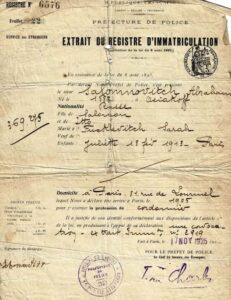

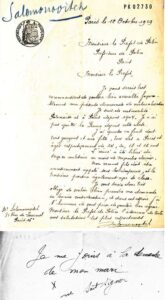

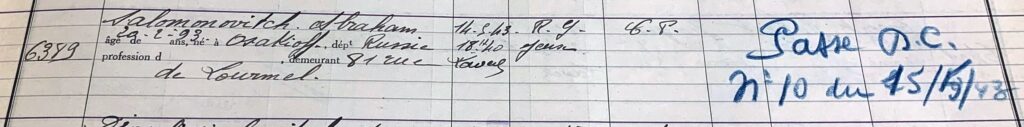

From Abraham Salomonovitch’s application for French citizenship – Archives

We also found out that he had learned French and spoke it well. The report ends as follows: “The applicant did not serve [the country] in any way. Aged 31 when war was declared, and having lived in France for nine years, he did not feel, when the danger arose, any love for France [69]. As a cobbler, he earns a good living and has no expenses. He says, however, that he is unable to afford anything”. For these reasons, the report was not in favor of his being naturalized as a French citizen. Nevertheless, on 3 September 1930, Abraham and his wife were granted French nationality [70].

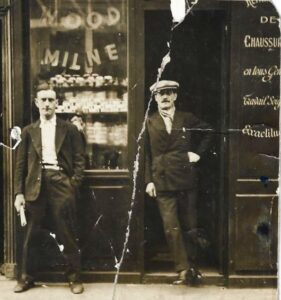

Isaac and his father Abraham in front of their little store on rue Lauriston – Family photo

War broke out, and then after the Germans occupied Paris, the noose tightened: on 14 May 1941, the Paris Police Headquarters appointed Marc Richard de Loménie as provisional receiver of Abraham’s store, thereby starting the Aryanization process. The store was in Isaac’s name by then, even though Abraham was still working there: did he think that handing it over to his son, who was born in France, would prevent it from being confiscated? On 27 May, the administrator wrote to the prefecture asking if Isaac met the required criteria to qualify as a craftsman.

In his report, he described the business: located at 18, rue Lauriston in the 16th district[71], it only measured about 3 feet by 6 feet! He said that Isaac worked alone, that he had no stock and that he earned approximately 60 francs a day. Given this negative response, Richard de Loménie closed down the store on 6 June. Stating that he had not found a buyer, he struck the business off the trade register. On the face of it, however, the business did not cease trading immediately.

On 6 August 1941, Abraham wrote a letter to Xavier Vallat the High Commissioner for Jewish Affairs: “I have lived in Paris since 1904, became naturalized as a French citizen in 1930, have three sons who, after completing their national service, were mobilized in September 1939, and one of whom is still a prisoner in Stalag VB n°9929. Until now, I worked as a cobbler in a small store rented in my name at no. 18, rue Lauriston. Having been forced to close down according to the decree on the status of Jews, I now find myself destitute, even though I still have to support my son and my family, and am unable to find work on account of my age. I would like to draw your attention to my rather unusual situation and ask for your kind permission to reopen my store so that I can provide for my family […]”. Unsurprisingly, Xavier Vallat did not respond kindly to this request!

But then, in a sudden and dramatic turn of events, Marc Richard de Loménie was dismissed from his post! It turned out that he was married to a Jewish woman! He was replaced by Raymond Molard, who also submitted a report: the store had been rented to a ‘coal merchant’, Mr Gaubert, for the sum of 1,200 francs a year. There were no accounts or cash books, but the turnover in 1939 was estimated at 6,700 francs, in 1940 at 8,000 francs and in the first quarter of 1941 at 2,950 francs. Isaac said that he continued to do a few repairs for private customers, which, according to a letter dated 18 May 1942, he was strictly forbidden to do [72]. As soon as he received the letter, Isaac closed the shop for good and left without leaving a forwarding address. The report concluded that his work was of “no real benefit to the country”! As stipulated by law, the proceeds from the liquidation of the assets were paid to the French Deposit and Consignment Fund.

Report on the Aryanization of the store 18, rue Lauriston, dated December 14, 1942

French National Archives

Obviously, this left the family in serious financial difficulty, and from then on they had to resort to various not exactly “lawful” ways of getting by. As a result, the French police arrested Abraham for the first time at 6.40pm on May 14, 1943. On May 17, he was sentenced by the 14th Criminal chamber of the Seine court to 15 days imprisonment in La Santé for “racing offences” (taking illegal bets on the public highway).

Abraham Salomonovitch’s detention record, dated May 14, 1943 – French Police Archives

Soon after that, an Inspector Dezan arrested him for a second time at 7.15pm on 31 May on grounds of his “race”. He was transferred to Drancy the following day, June 1st. HIs wife Sarah was arrested in July of the same year, also on “racial” grounds. They were both deported to Auschwitz on Convoy 58 on 31 July 1943 [73]. They were later declared to have died on August 5 [74], which implies that they were murdered in the gas chambers as soon as they arrived, without ever being admitted to the camp. Their deaths were recorded in the civil registry of the 15th district of Paris on April 30, 1947.

The day after Abraham was deported, the Ministry of Justice asked the Paris Police Headquarters to carry out an investigation into him. We have the result of this investigation, dated January 18, 1944, by which time Abraham was long dead! It reveals that the German authorities had sealed up his apartment at 81 rue de Lourmel in July 1943. The report also states that his store, at 18 rue Lauriston, was closed in accordance with the “racial legislation” and that he had been doing odd jobs in the neighborhood for some time. It goes on to say that he was unable to write French, but could read it, and that he had “never drawn attention to himself, from either a national or political point of view”. Lastly, we see that “his wife and children, Isaac and Juliette, left their home after the father was arrested, and that they had been searched for, but to no avail. The same is true of David, who rarely returns home”. In view of his conviction for taking bets on the street the report concludes: “in view of the aforementioned facts and his limited integration”, the prefecture is leaving it up to the Ministry “to assess the advisability of his remaining a member of the French community”!

In 1962, he was officially granted the status of “political deportee”, meaning that he was deported on political grounds [75].

2. Ferdinand, Isaac and Juliette: his brothers and sister

Family photo taken in around 1916. From left to right: Ferdinand, David, Abraham, Juliette and Sarah, with Isaac at the front, in the middle – Family photo

Photo 1: Left to right: Ferdinand, Isaac and David

Photo 2: Isaac and Ferdinand in front of their little workshop

Family photos

Ferdinand was born on June 19,1905 in the Saint-Antoine hospital in the 12th district of Paris. According to his birth certificate (and indeed his marriage certificate), his parents were Ferdinand and Sarah Salomonovitch [76]. In 1927, he began 18 months of national service in the 129th Infantry Regiment at le Havre, in the Seine-Maritime department of France, which ended in November 1928.

Ferdinand in his army uniform / Ferdinand in the prison camp

Family photos

He married Jeanne Renée Burtey in Lisieux, in the Calvados department of France, on July 8, 1933. He was taken prisoner of war in 1939, and was living at Bois-Colombes in the Hauts-de-Seine department in 1944 [77].

Ferdinand wedding to Jeanne Burtey – Lisieux, July 8, 1933

Family photos

Isaac was born on December 17, 1910 at his parents’ home at 81, rue de Lourmel in the 15th district of Paris. As a young man, he worked with his father in the little cobbler’s workshop at 18 rue Lauriston, in the 16th district. In 1929, as we have previously discussed, he was earning 20 francs a day. Given how tiny the workshop was, one can only imagine that young Isaac used to collect shoes for his father to repair and then return them to the customers, while at the same time learning the trade. He later took over the store, as mentioned above but, as a Jewish business, it was closed down under the Aryanization legislation. Unlike so many other members of the family, Isaac managed to avoid being rounded up and survived the war.

We catch up with him again in 1947, when, as his parents’ beneficiary, he put together a compensation claim. He stated that three of the “non-returned” couple’s children were still alive. In a record from 1961, only he and his sister Juliette were listed [78]. At that time, Isaac was living at 81, rue de la Convention in the 15th district. In 1946, he married Marie-Louise Chemineau and the couple went on to have one child, Armand, who was born in 1953.

In 1964 when he was living at 38, rue Gutenberg in the 15th district, he had power of attorney for his sister Juliette and was granted a “payment of compensation to beneficiaries of deportees” of 276 francs. A paltry sum, given that he had lost his parents, that his workshop had been confiscated, and that the family had suffered financial difficulties and anxiety for so many years. He died in 1981 in the 15th district, where he had lived all his life.

Isaac and Marie-Louise Chemineau

Family photo

Juliette, the youngest child, was born on February 18, 1913 in the 15th district of Paris. In 1929, she was a saleswoman on rue Tiquetonne and then, according to the 1936 census, she was living on rue Lourmel and working, still as a saleswoman, at 3, rue du Commerce, all in the 15th district. After the war, she married Henri Gabriel Musy in Lyon, in the Rhône department of France. They had no children. She died in Villeurbanne, Lyon, in 2007.

Juliette / Juliette and Henri Musy – Family photos

Family ration coupons, kept by Armand Salomonovitch

3. David

David, the second son, was born on January 29, 1909 in the Rothschild hospital in Paris. At the time, his parents were living at 9, Passage Gustave Lepeu inn the 11th district. The following year, the family moved to 81, rue de Lourmel in the 15th district, where David lived until he got married. He began his national service on October 29, 1929 and served in the 26th Infantry Regiment in Nancy, in the Meurthe and Moselle department of France.

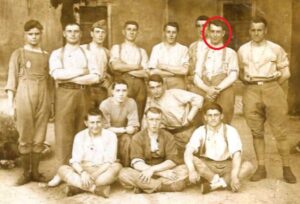

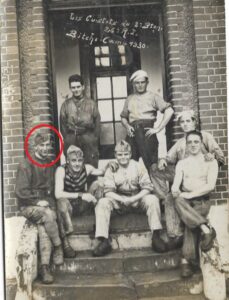

He is pictured in a number of photos at the army camp in Bitche, in the Moselle department of France, just a few miles from the German border. He was a member of the camp kitchen staff.

Family photos

He was called up for military service in September 1938, and joined the infantry on August 26, 1939. He was discharged in 1940 under a law that applied to fathers of families with four or more children [79]. Born when his parents were living in Passage Gustave Lepeu, he moved to 81, rue de Lourmel with them in 1910. He lived there until he got married, in 1932, at which time he and his wife then moved to 14, rue des Quatre Frères Peignot in the 15th district, where he lived until 1944.

Photo 1: David Photo 2: Madeleine Picot in the 1960s – Family photos

On September 3, 1932, he married Madeleine Marguerite Picot, who came from the Haute-Saône department of France. She was a chambermaid at the time, and lived at 30 avenue Bosquet in the 7th district of Paris. His brothers were witnesses at the wedding. The couple appear to have got married in a hurry, as their first child, Micheline, was born just two months later, on November 20. She was the eldest of four daughters, the others being Juliette Gilette, who was born on February 9, 1934 [80], Nicole, born November 25, 1936, and Jacqueline, born June 18, 1938.

When his parents were arrested and deported, in July 1943, this no doubt prompted the family to take action. The last two photos of David in were taken in the Creuse department of France in 1943.

In the photo on the right, David and his wife with two of their daughters, Micheline and Jacqueline

Family photos

On 9 September, 1943 [81], he was in Lyon, in the Rhône department, where he rented a furnished room at 25, rue du Bœuf, which he shared with his first cousin Maurice Salomon [82]: it was there that they were arrested on May 19, 1944 [83], on both racial and political grounds [84]. A record submitted as part of an application to have David recognized as having “Died for France” reveals that he went by the “nom de guerre” of Louis Nicolas [85], although we do not know where this name came from. He was initially imprisoned in Montluc jail in Lyon. On July 3, he was transferred to Drancy camp [86] from where he was deported to Auschwitz on Convoy 77 on July 31, 1944, a year to the day after his parents.

25, rue du Boeuf in Lyon, a narrow side street

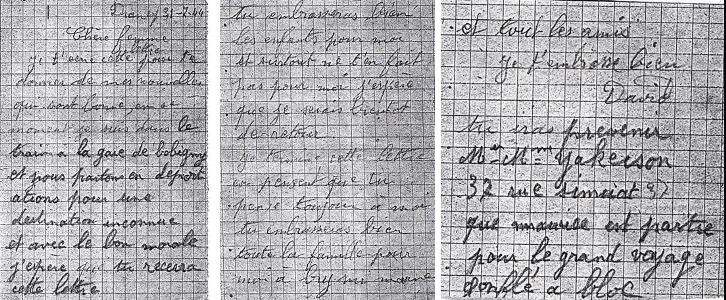

David never came home. The family still has a final and deeply moving reminder of him: the last letter he ever wrote, on July 31, when he was already on the train bound for Auschwitz. This is what it said:

Drancy, July 31, 1944

Dear wife,

I’m writing this letter to tell you my news, which is good – at the moment I’m on the train in Bobigny station and we’re being deported to an unknown destination and in good spirits. I hope you’ll receive this letter and give the children a big kiss for me and, above all, don’t worry about me, I hope I’ll be back soon.

I end this letter with the thought that you are still thinking of me. Please give a big hug to my family in Bry-sur-Marne[87] and all our friends.

You must tell Mr. and Mrs. Yakerson at 37 rue Simart that Maurice [88] is off on the long journey full of energy.

David’s last letter – Family archives

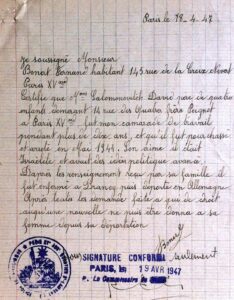

On November 27, 1945, Madeleine Picot, who still had no information about her family’s whereabouts, wrote to the French Research Department to find out what had become of her husband and parents-in-law. Between then and 1947, she gathered evidence and put together a file that bears witness to the fact that even at that late stage, she was still hoping that they might come home. The file includes several testimonies from neighbors about David’s “disappearance”.

File on David Salomonovitch – Shoah Memorial archives

On December 8, 1947, his death was recorded in the civil register at the town hall in the 15th district. He was initially declared to have died on July 31, 1944 in Drancy, but the record was amended in 1994 to state that he died on August 5, 1944 in Auschwitz [89]. In February 1948, the words “Mort pour la France” (Died for France) were added to his birth and death certificates. On May 5, 1954, David was granted “political deportee” status [90]. Later that year, his widow received a cheque for 12,000 francs “compensation for deportees’ beneficiaries”.

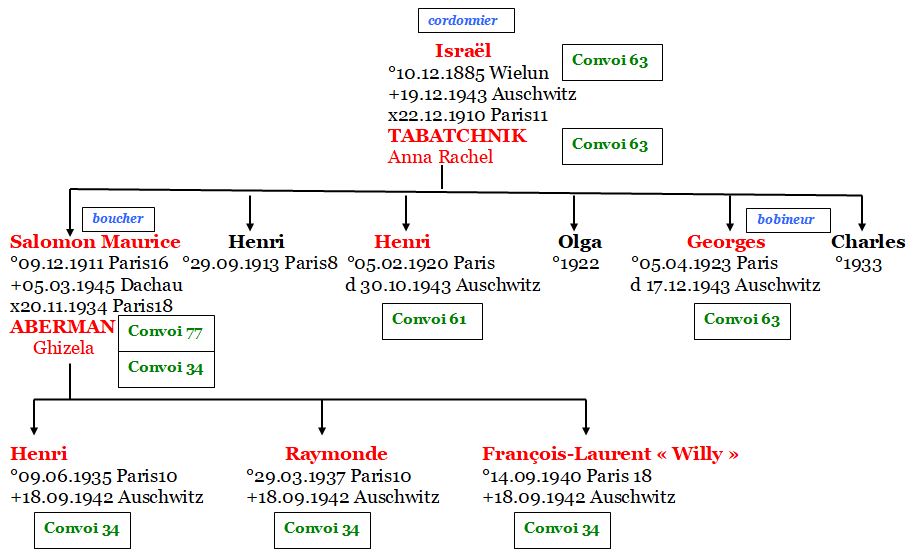

VI – ISRAÊL (1885-1943) AND HIS DESCENDANTS: A BRANCH DECIMATED BY DEPORTATION

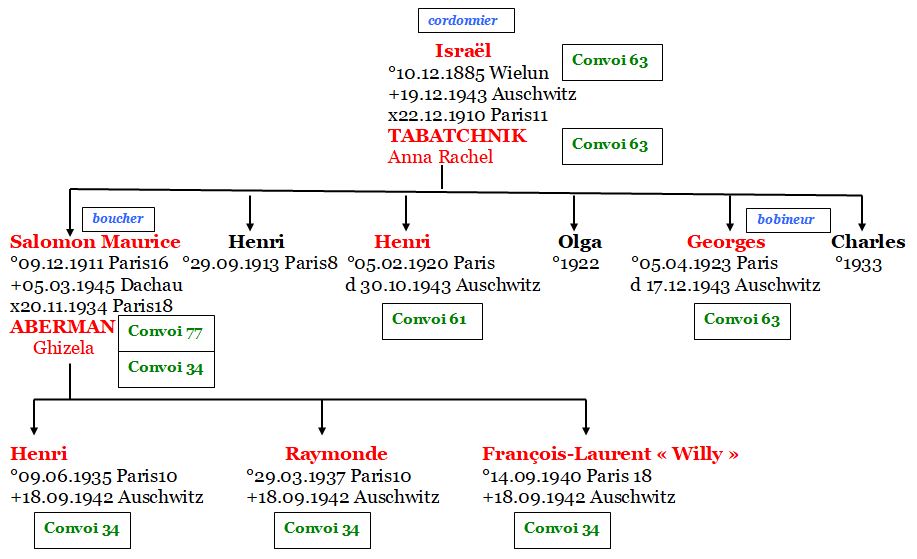

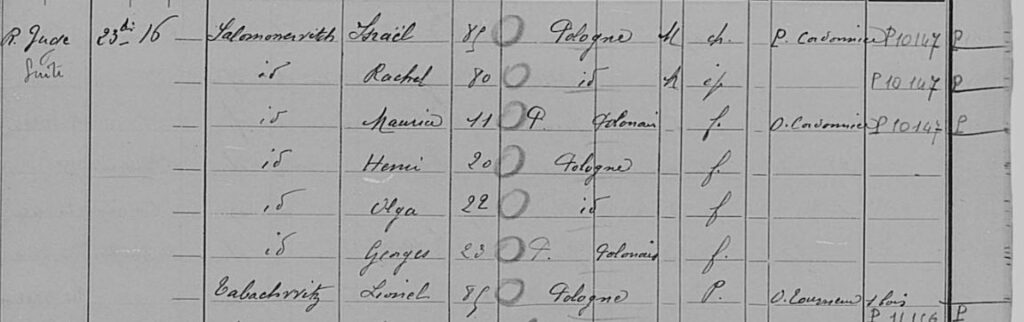

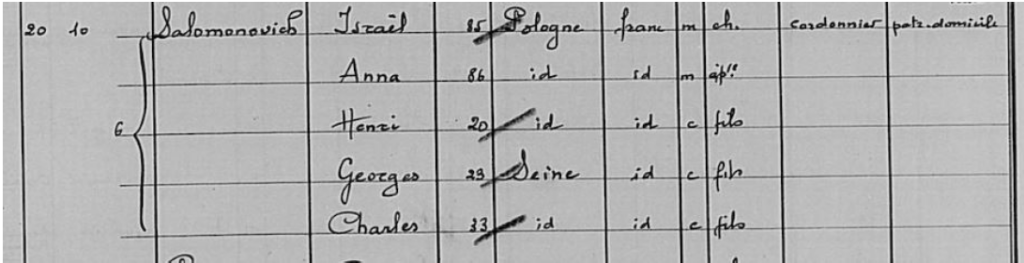

Israël, who was born in 1885 in Wieluń, was the father of the worst-affected branch of the family. As a result, it is also the least well-documented. Because we know so little about Israël’s relationship with the rest of the family, we cannot be sure whether any members of this branch appear in the photos featured in this biography. Israël married Anna Rachel Tabatchnik on December 22, 1910, in the 11th district of Paris[91]. He was a cobbler at the time and was living at 77, rue de Longchamps in the 16th district. She hailed from Gostynin, a village north of Lódź, in Poland [92]. The couple went on to have six children: Salomon Maurice (1911), Henri (1913 in the Beaujon hospital), Henri (1920), Olga (1922), Georges (1923) and Charles (1933).

The first “mystery” is this: while Salomon Maurice (not to be confused with his first cousin, born in 1903 and bearing the same first names – see part IV) was born in the 16th district, and the first Henri (1913) was born in the 8th district, there is no trace of the births of the other children in the Paris Civil Registry [93]. Here is what we have: When they were first married and had their first child, they were living at 77, rue de Longchamps in the 16th district. In 1913, when Henri was born, they were living at 53, rue Legendre in the 17th district and by the time of the 1926 census, the family was living at 23, rue Juge in the 15th district. In the 1931 and 1936 censuses, they were living at 20, rue Bachelet in the 18th district. Something else: Henri (b. 1913) and Olga (b. 1922) are not listed anywhere after that. This would suggest that they died when they were young, and yet there is no record of them in the death registers [94].

Photo 1: 23, rue Juge

Photo 2: 20, rue Bachelet

Places in this case, rather than photos of the people! Source: Google Maps

1926 census listing for 23, rue Juge (15th district) – the only record that we found that lists all of the couple’s [surviving] children.

1936 census listing for 20, rue Bachelet (18th district) – In the intervening ten years, Maurice Salomon had left the family home, Olga was no longer listed (died young, as did her brother?) and Charles had been born.

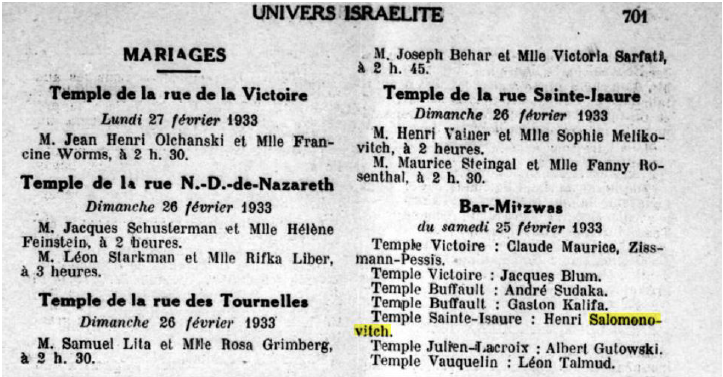

Announcement of Henri’s bar-mitzvah on February 25, 1933 at the Saint-Isaure synagogue in Montmartre. Source: L’Univers israélite, February 1933.

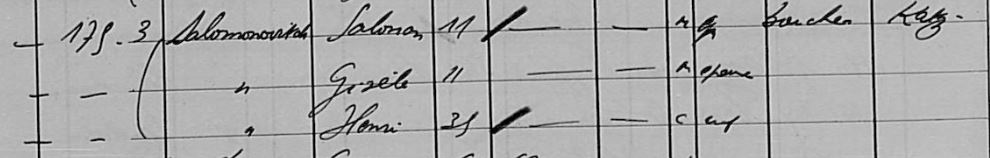

In 1934, Salomon Maurice married Ghizela Aberman, a Romanian Jewish woman in the 18th district of Paris. He was a butcher at the time, he and his wife moved to 35, rue Simart, also in the 18th district, where they were still living at the time of the 1936 census. The couple had three children: Henri in 1935), Raymonde in 1937 and François-Laurent, (who is listed on the Shoah Memorial website as sur le site as Willy, or Villy), in 1940.

1936 census listing for 35, rue Simart (18th district)

The Second World War was soon to decimate the entire family.

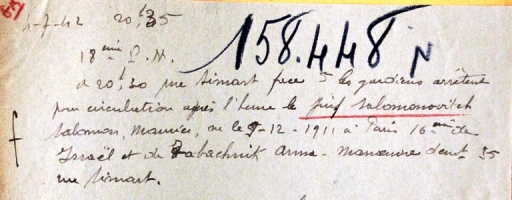

The first warning shot was fired on July 4, 1942: at 8:30 pm (30 minutes after curfew time), Salomon Maurice was arrested outside 5 rue Simart (he lived at number 35) on the grounds that he was out on the street when it was forbidden, and was taken to Drancy the following day. He was released on July 11. We do not know the exact date, but at some point, his wife Ghizela and their three very young children (Henri was 7, Raymonde 5 and little Willy just 2) were also arrested and sent to Drancy [95].

Report of Salomon Maurice’s arrest, July 4, 1942 – Police Archives

(general intelligence file, ref. 77 W art 347 – 158 448

At 8:55 a.m. on September 18, 1942, Convoy 34[96] left the Bourget-Drancy railroad station bound for Auschwitz, with 1,000 Jews on board. It arrived on September 20, and Ghizela and her three young children would most likely have been sent to the gas chambers and murdered immediately [97]. Salomon Maurice was thus left alone in Paris, and it was probably around this time that he decided to cross the demarcation line into the so-called Free Zone.

On October 28, 1943, his brother Henri (born 1920) was also deported from Drancy (we do not know when he was arrested or interned there) [98], abord Convoy 61, final destination Auschwitz. He did not survive [99]. A small but interesting detail, even though we have no way of working out what happened exactly: Henri’s Drancy record card says that he was born in Gostynin, a village in Poland that we mentioned earlier. This leaves us guessing: it could explain why there are no records of Maurice Salomon’s siblings’ births in Paris after 1913. Then again, it seems unlikely that he was born in Poland, unless Israël and Anna Rachel moved back there between 1913 and 1923 (after that, they are listed in the census of Paris). But given how difficult this would have been, in particular as the family were not French citizens, it’s hard to imagine that they would have sent off on such a venture with such young children in tow. Aside from that, something else does not quite add up: Georges Drancy record card [100] says that he was born in Paris, and yet we found no record of his birth there.

Less than two months later, Salomon Maurice lost his parents and his 20-year-old brother Georges. They were deported from Drancy on Convoy 63 on December 17, 1943, which arrived in Auschwitz on December 20. As Israël and Anna Rachel were in their sixties, they were probably murdered in the gas chambers as soon as they got there. Georges, like Henri, never returned from the camps. By the end of 1943, with the possible exception of his brother Charles, born in 1933 (we do not know what happened to him), Salomon Maurice had lost his entire family: parents, siblings and children.

A few months later, we catch up with him again, together with his cousin David, in a rented room on the rue du Boeuf in Lyon, as we discussed in the section on David. It was there that he was arrested on May 19, 1944 and taken to Montluc prison. Together with his cousin, he was transferred to Drancy on July 3, 1944, and deported to Auschwitz on July 31, 1944 on Convoy 77. Unlike David, who was later declared to have died soon after he arrived, Maurice Salomon was selected to stay in the camp and work. Sometime later, although we do not know exactly when, he was transferred to the Dachau camp, where he was assigned prisoner number 139.439. He was later declared to have died there on March 5, 1945, just under two months before the Americans liberated the camp. His death was eventually entered in the register of the 5th district of Lyon, but not until 2012!

Unless one of the Israël’s children miraculously survived somehow, there are no remaining descendants of this branch, which the current family members did not even know existed.

SOURCES – THANKS

Archives services:

- French National archives

- Police Headquarters archives

- French Historical Defense Service archives in Vincennes

Websites

- Online civil registers (Paris, Seine-Saint-Denis, Hauts-de-Seine and Val-de-Marne)

- 1926, 1931 and 1936 censuses, online

- Cantal departmental archives: 9NUM 7 et 9NUM 20-21

- Rhône departmental archives

- Geneanet

- Mémoires des Hommes

- Gallica

- 589-(03) Ch. Eggers (memorialdelashoah.org)

- MARC Sandra (celeonet.fr)

- Wikipedia

We would like to thank the Salomonovitch family, especially Estera, Armand, Alain, and Catherine Rougeul, for allowing us not only to share their family’s photographic legacy, but their invaluable knowledge and family anecdotes.

Notes and references

[1] Juliette Salomonovitch, born in 1909, was known to the Salomonovitch family only as “Aunt Julia”.

[2] There are only four exceptions: three people born in Poland, including one in Lódź, and a minor branch from Belgrade in Serbia.

[3] The Jewish population here was hit particularly hard during the war: during this period, the Jews in Wielun, some 4200 in all, were eliminated on the spot, transferred to the Łódź Ghetto or deported straight to the Chełmno extermination camp. Sura Salomonovitch, who stayed behind in Poland, was among them.