Moïse CHETOVY

Moïse Chétovy’s parents were Jacob Chetovy and Ester Mora. He was born in Constantinople, now Istanbul, on May 3, 1893[1]. We know nothing about his early life. We imagine that he moved to France, probably with his parents, in response to the political climate in Turkey. One of the reasons that Jews left Turkey was a change in the status of ethnic minorities (Armenians, Greeks, etc.) in the former Ottoman Empire, but there were often also other more complicated explanations[2].

The Jews, who had built up prosperous communities in the former Ottoman Empire, were then confronted with political change and ever-increasing hostility. Political pressure and pogroms, particularly at the end of the 19th and beginning of the 20th century, prompted large numbers of Jews to emigrate to other areas, in particular to Western Europe, the United States and Palestine which was then under British mandate. France, which was a popular destination for Jewish emigrants, became home to many Jews from Turkey, including Moïse Chetovy, who appears to have arrived in 1919 and set up home in the 11th district of Paris. These Turkish Jews made a significant contribution to Jewish traditions and diversity in France.

Moïse married Rosa Nichli, who was born in 1895. Her parents were Marco Nichli and Oro Varon. They were married on December 13, 1919 in the 11th district of Paris. They appear to have been neighbors at the time, since both were living at 113, rue de Montreuil, also in the 11th district[3]. According to some local people, the families who lived there were not very well-off but all got on well together[4].

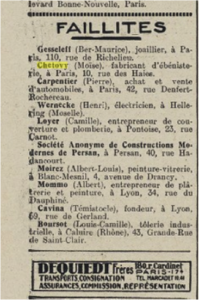

Moïse and Rosa went on to have three children: Ester, Jacob, and Mordo. Moïse ran his own cabinet-making business at 10 rue des Haies in the 20th district of Paris. His name appeared in the newspapers a few times[5], but only to report that his business went bankrupt in late September 1928. There was an announcement in Les Echos on September 22, 1928, for example.

One of the newspaper announcements. Source: gallica.bnf.fr

During the war, Moïse had little money and no income, and applied to the UGIF (Union Générale des Israélites de France, or General Union of French Jews) for financial support for his family[6]. This leads us to believe that neither he nor his wife had been able to find work, which appears to have been the case from 1928 to 1944[1].

After the Germans invaded France and the armistice was signed, the Vichy government carried out a census of foreign Jews. A roundup, known as the “green ticket” roundup, took place on 14 May 1941. Foreign Jewish men were summoned to local police stations and then arrested. Moïse, as a Turkish citizen and a Jew, may have been caught during a later roundup. He was arrested in August on account of his “race”[7]. He was interned in Drancy camp on August 21,1941 but released again on November 5 due to ill-health[8]. Moïse did not move away however, he and his family stayed on at 113, rue de Montreuil. They probably could not afford to move, given that they had no income.

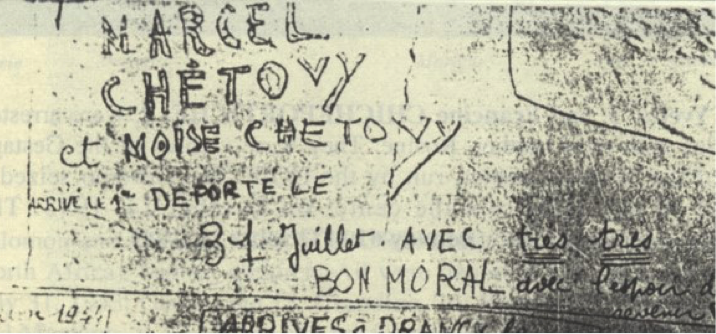

On June 9, 1944, Moïse was arrested again, at his home, an hour or so after the German police had stopped his son, Mordo. According to the arrest record, Mordo was arrested “during a time of alert, with his star”[9]. Moïse was taken to Drancy, where he was assigned the serial number 24680[10]. His wife, Rosa, his other son Jacob and his daughter Ester were not arrested. Moïse was then deported to Auschwitz on Convoy 77, together with his son, on July 31 1944.

Following the Allied landings in Normandy on June 6, 1944, the Nazis intensified their “final solution” campaign. They deported as many people as possible in quick succession in the summer of 1944. Paris was liberated on August 25, 1944. Convoy 77 was the last large transport to leave Drancy, three weeks before the liberation. The numbers of people exterminated in in the killing centers also increased rapidly. Moïse was not sent to the gas chambers when he arrived in Auschwitz, however, despite his advancing years. He must have been selected for work, possibly because he was a skilled cabinet maker. He was subsequently transferred to Buchenwald[11], probably having passed through other camps in the meantime, where he died on December 16, 1944. He died on the same day as his son, who, according to the death certificate issued by the Nazi authorities, died of “heart failure”. Heart problems would often be given as the cause of death in order to cover up the true reasons for the deaths of Jewish deportees[12].

Notes & references

[1] Death certificate dated June 12, 1956, file on Moïse Chetovy, © Victims of Contemporary Conflicts Archives Division of the Ministry of Defense Historical Service, in Caen, ref. 21 P 435 981 4089 © DAVCC 5112.

[2] Annie Benveniste, “Récits de migration, récits de persécution. La « petite Turquie » entre mémoire et fiction” (Stories of migration, stories of persecution. ‘Little Turkey’ between memory and fiction) Archives Juives (Vol. 42), 2, 2009, p.41-56.

[3] Marriage certificate, Paris archives, act n° 3577, ref. 11M 495.

[4] The Chetovy family are mentioned in the biography of Rebecca Farsy, who was also deported on Convoy 77, and whose children went to the same school as the Chetovys.

[5] La Liberté, September 25,1928.

[6] Union Générale des Israelites de France records, Folder 22.3.1, Reel MK 490.110, Box 120-121 (RG 210).

[7] File on Moïse Chetovy, © Victims of Contemporary Conflicts Archives Division of the Ministry of Defense Historical Service, in Caen, ref. 21 P 435 981 4089 © DAVCC 5127.

[8] File on Moïse Chetovy, © Victims of Contemporary Conflicts Archives Division of the Ministry of Defense Historical Service, in Caen, ref. 21 P 435 981 4089 © DAVCC 5112.

[9] File on Moïse Chetovy, © Victims of Contemporary Conflicts Archives Division of the Ministry of Defense Historical Service, in Caen, ref. 21 P 435 981 4089 © DAVCC 5106.

[10] File on Moïse Chetovy, © Victims of Contemporary Conflicts Archives Division of the Ministry of Defense Historical Service, in Caen, ref. 21 P 435 981 4089 © DAVCC 5109.

[11] File on Moïse Chetovy, © Victims of Contemporary Conflicts Archives Division of the Ministry of Defense Historical Service, in Caen, ref. 21 P 435 981 4089 © DAVCC 5114.

[12] Eva Bitton and Théophile Leroy, “Enregistrer la mort à Auschwitz : le certificat de décès comme source pour l’histoire de la Shoah” (Recording death at Auschwitz: the death certificate as a source for the history of the Holocaust), 2022, https://lubartworld.cnrs.fr/enregistrer-la-mort-a-auschwitz-le-certificat-de-deces-comme-source-pour-lhistoire-de-la-shoah/

Français

Français Polski

Polski