Peril ZANVIL

Photo: © Adrian Aresteanu, family archives

Following in the footsteps of Peril Zanvil; a historical investigation

Do not just say that in 30 years,16 million immigrants passed through Ellis Island

but try to put into context

those sixteen million individual stories,

sixteen million stories, identical yet distinct,

of those men, women, and children driven

from their native land by famine or poverty,

or by political, racial, or religious oppression,

leaving everything behind—village, family, friends

—taking months and years to set aside

the money for the trip,

finding themselves here, in a hall so vast that they

would never have dared to imagine that such a huge place

could exist anywhere,

lined up four by four,

waiting their turn

the point is not to have pity, but to understand.

Georges Pérec [1]

Each new project is like a jigsaw puzzle, for which we have just a few scattered pieces at the start of the year, some distinct, some linked, and some with no apparent connection between them. Our role is to seek out new pieces to add to the puzzle: records, of course, and also testimonials, meetings, visits, reading material etc.

At the start of the year, when we introduce the students to the project, we only outline the overall objective, which is to write the biography of Peril Zanvil, who was deported on Convoy 77. We explain to the students that anything is possible, to adapt, expand on and lend a more artistic dimension to the initial project of writing a biography, so that everyone can make their own contribution to the shared achievement and, above all, take ownership of it. The ultimate structure of the puzzle then depends on whether (or not) they find new pieces, and also on what suggestions each individual, whether student, artist or teacher, comes up with. Each of them, in his or her own way, takes on the project and adds to it with his or her own ideas and creative talents.

Peril Zanvil’s biography was written in French and History class by the 9th grade students of class 3e1, with the guidance of their teachers Clarisse Brunot and Claire Podetti. It is the result of a fruitful encounter with Adrian and Géraldine Aresteanu. Adrian’s family archives enabled us to get to know Peril a little better and, above all, to put a face to the name. Our investigation uncovered some additional records about Haîm, Peril’s husband, including his application for French citizenship by naturalization and his military service record.

What we did with the students was first and foremost a historical study, a thorough investigation into Peril’s life. The point of the project was not to feel sorry for her, as Georges Pérec so aptly wrote, but to better understand what her life was like before she was murdered in Auschwitz, and in doing so to continue Serge and Beate Klarsfeld’s work by going beyond a mere name, and retracing her journey.

We were not able to write a complete biography from the records we found. Many questions remain unanswered: what was Peril’s childhood in Romania like? When did she move to France? Did she ever see her Romanian family again? The students soon began to understand that the Holocaust was not just about the death and disappearance of individual people, but also about erasing all traces of them so that it would be impossible, later on, to piece together the lives of the people they murdered.

This year we decided to translate Peril Zanvil’s biography into all the languages spoken by the students, their parents and/or grandparents; 14 languages in all. The variety of foreign languages (Peuhl, Gouro, a West African language, Tunisian and Algerian Arabic, Haitian Creole, Hebrew, Russian, Tamil, Albanian etc.) and scripts shows the great diversity and breadth of knowledge among the students in the class. Two Romanian students, Adelina-Maria Bocancea and Maria-Daniela Gusa, translated the biography into Romanian.

Peril’s story has been passed on within the students’ families, and has in some cases provided an opportunity for them to explore their own family history. Peril is now part of our collective memory, and her story, which was so difficult to reconstruct, is also partly our own. The Holocaust is no longer just about the European memorial at Auschwitz, the liberation of which we commemorate every year on January 27; it’s also about a “living memory”, one that is being recorded through this collective narrative of a shared history. This will be rekindled next year, when students from the Estienne school of typography will be working on a new project based on the multilingual biography of Peril Zanvil.

Biography of Peril, Perl or Pauline Zanvil, née Juster

©Géraldine Aresteanu

1. Growing up in Romania

Peril was born in Tzibana or Jassy on May 10 or 12, 1898[2]. Her maiden name was Juster. Her mother was called Pesla, and her father Jano or Janeu, depending on the records. Peril had four sisters. The little information we have gathered about Peril’s life in Romania all comes from French archives, and there is very little to go on. We do not know why Peril emigrated to France, but the anti-Semitic climate in Romania in the 1920s may well have been one of the reasons that she left.

Historical context: the departure of the Jews from Romania[3]

Anti-Semitism was rife in Romania at the end of the 19th century, particularly in the city of Jassy. It was there, in the early 1920s, that Alexandru Cuza, together with Nicolae Paulescu, reorganized the anti-Semitic National Christian Defense League, which called for Jews to be excluded from Romanian society. Both men published fiercely anti-Semitic texts in the 1920s.

In 1927, the party adopted the Romanian flag with a swastika in the center as its symbol. It demanded that Jews be stripped of their political rights, that their Romanian citizenship be withdrawn, and that all Jewish land and property be redistributed. Following a split in the party, the Iron Guard was founded in 1927.

Students from the university where A. Cuza taught carried out a number of often bloody disturbances in the Jassy area.

2. The move to Paris

Peril married Haïm Leib Zanvil in the 18th district of Paris on February 12, 1927[4]. Did she meet her future husband in France or Romania? There are no records to answer this question. Haïm was born on November 13, 1893 in Botosani, Romania. He first married Sepi Posner[5], also a Romanian, on May23, 1918. One of the three witnesses to this first marriage was Jancu Haimovici, whose signature can be seen at the bottom of the marriage certificate[6]. Jancu and Haïm lived at the same address, 13 rue Bachelet in the 18th district of Paris.

© Digital archives of the 18th district of Paris, dated 1918, certificate N° 958

Haïm and Peril’s wedding was immortalized in a photo. But was it actually taken at their wedding, or beforehand? In it, they are posing and staring straight ahead at the photographer. Peril is dressed all in white with a crown of pearls in her hair and her long white train has a bouquet of flowers placed on it. Haïm is wearing a suit and gloves and holding a hat. Both of them have a faint smile on their lips.

© Adrian Aresteanu, family archives

The couple set up home at 68 rue des Poissonniers in the 18th district of Paris. They lived in on third floor[7] since1931, as evidenced by the census and the confiscation record.

© Digitized Archives of Paris, 1931 census, 18th district, 68 rue des Poissonniers, Goutte d’Or district

© 68 rue des Poissonniers (Google street view)

68 rue des Poissonniers is now used as a fabric shop and a bar

Historical context: Romanian Jews in Paris [8]

In June 1941, in the Seine department, there were 2,558 heads of households who were Romanian Jews. According to Serge Klarsfeld, there were between 6 and 7,000 Romanians in Paris at that time, mainly living in the 11th and 18th districts.

3. Haïm, a bespoke tailor

Haïm was a bespoke tailor, making suits and clothes to order for private customers. His boutique was also at 68 rue des Poissonniers.

In the early 1930s, Peril and Haïm employed a young clerk, Hers Askenasi, who helped Haïm in his workshop: “On rue des Poissonniers, there is a tailor called Mr. Zanvil (…) Mr. Zanvil’s workshop is on the first floor. A very thin wall separates it from the street. I am an apprentice at the far end, and when someone rings the bell, I have to creep around a sort of low wall. I go to see whether it’s a customer or a tramp. If it’s a tramp, my instructions are not to open the door”[9]

This young clerk also helped Peril with household chores: “I have to do the copper for her. Once the kitchen copper is polished, I go back to my work.” He was not very fond of Peril: “Madame Zanvil hadn’t heard of Shakespeare, and when someone tells a joke, she constantly interrupts, asking about the experience, the difference between reality and fabrication: where, when, how. Farwoust? Why?” Peril had little or no formal education, as can be seen from her letters, which are written in Romanian but sometimes difficult to read or understand, and include some Yiddish phrases.

© Adrian Aresteanu, family archives

4. The birth of the children

Jacques was born on July 17, 1928 at the Rothschild hospital on rue Santerre in the 12th district of Paris. He was a cute little boy and his parents took him to Maurice & Cie photographers on rue Ramey in Montmartre, and sent photos back to family in Romania.

© Adrian Aresteanu, family archives

Photos taken in 1929 © Adrian Aresteanu, family archives

Peril and Haïm look a happy couple, as confirmed by this photo of the couple taken in the same photo studio and sent with this inscription on the back “To mark 1929”.

Haïm’s younger brother visited them for Passover. Peril described the Romanian meal they shared for Pesach as follows: “Mrs. Tucherman ate at my house, she cooked for me. She made gefiltefish, fried fish, chicken soup, leek dumplings, cicola, sweet lotchis and lotchis, walnut cake, bortsch. I cooked all this on Saturday, and we ate it with Zanvil’s younger brother” [10]

This happiness was short-lived, however, as Jacques fell ill with osteoarticular tuberculosis and had to be put in plaster and sent to the Saint François de Sales Institute at Berck plage, a seaside town on the north coast of France. In a letter to her sister Caroline, Peril says that they were going to Berck to see some medical specialists: “This suffering I have to endure, no mother suffers as much as I do with my poor child. You can imagine Zanvil asking the manager how long Jacques has to stay in plaster, and the manager saying it might be a year or a year and a half. You can imagine the state I was in when I heard this. But we’re not going to just leave it at that. I’m leaving for Berck-Plage at 7am on April 20. There are doctors there and we’re going to go and see what can be done. I’m going for 6 months, until after September, so help me God”.[11]

A photograph taken on the beach at Berck shows Peril and Haïm, hand in hand, on May 1, 1930. Three weeks later, on May 24, Jacques died, at the age of two, at the family home.

Berck plage, May 1 1930, © Adrian Aresteanu, family archives

A second ray of sunshine came along when Gisèle was born, on March 11, 1931. Just two years later, however, tragedy struck again when Gisèle died on April 11, 1933 at the Pierre Bretonneau Hospital on rue Carpeaux in the 18th district of Paris[12]. The children’s first names, both of which were French, show how keen the couple to integrate into French society and to stay in the country. Haïm also applied for French citizenship by naturalization in 1923, which was granted in 1926.

© Adrian Aresteanu, family archives

©Hôpital Pierre Bretonneau, Paris. (https://paris-promeneurs.com/lhopital-bretonneau/)

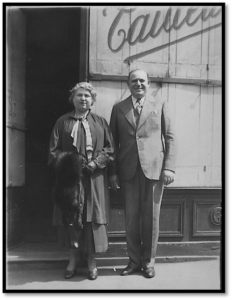

5. Life as a couple again

Peril and Haïm had their photo taken in front of their store in Paris. Smartly dressed, they showed their social ascent and professional success in France. They help their families back in Romania financially, as Peril says in one of her letters: “I sent the money on Wednesday 13th. Please confirm immediately when you have received the money”[13]

© Adrian Aresteanu, family archives

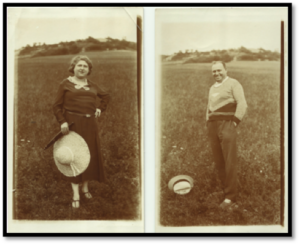

The photo is a little blurred and was probably taken by a friend. In fact, on the back of the photograph, Peril said that she had not had the photographs retaken because she did not think they were very good. One photograph suggests that Haïm and Peril may also have had a small allotment somewhere near Paris. Peril is gardening and there is a little shack in the background.

© Adrian Aresteanu, family archives

Since they no longer had any children, Peril and Haïm may have gone on vacation, as these photos taken in a hilly area suggest. Unless perhaps Haïm was sick at the time? In one of the photos, he is leaning on a cane. This photo must have been taken in the 1930s, so he was not so old. Nevertheless, he was in poor health and may have been gassed during the First World War [ 14]. Many soldiers who were gassed suffered from lung problems afterwards: pneumonia, chronic bronchitis, tuberculosis etc. Peril mentions her husband’s illness in 1935, in a letter to Aron Berkovi: “and my man is not like other men. He’s so weak he doesn’t have the strength to work. We’ve had a very tough winter. There wasn’t much work, and there isn’t now, and he can’t work anyway.”[15]

Haïm was a volunteer soldier in the First World War. On August 22, 1914, he was drafted into the 2nd Foreign Regiment.

We are not sure whether Haïm was gassed or not, but his service record states that he was “discharged the second time due to “flat feet” by the Blois reform commission on September 29, 1914 (…) then “definitively discharged, 20% invalidity, by the Orléans reform commission on June 24, 1921 due to sclerosis of the left apex with no worsening lesions. Sputum analysis negative.”

© Adrian Aresteanu, family archives

6. The war, the confiscation of the store and Haïm’s death

The store closed in 1941, when Haïm was admitted to the Sanatorium de Saint Martin du Tertre, in the Val d’Oise department of France. This was a huge hospital that provided specialized care for tuberculosis patients.

© Chatsam, commons.wikimedia.org

The store was then “Aryanized”, in other words confiscated by the State, and a Mr. Goujaud was appointed administrator, followed in February 1941 by a Mr. Montovert de la Tour. Mr. Montovert la Tour took over eighteen months to take over the store, as he wrote to his manager, complaining that: “The Zanvils went to a great deal of trouble to leave their store vacant, and for various reasons and pretexts kept delaying handing over the keys to the owner” [16]. On March 3, 1942, he started proceedings requesting: “the striking off of the Zanvil business from the Trade Register and the Patent Roll, and the withdrawal of the buyer’s card”. He confirmed this to his manager on October 20, 1943: “The Jewess has been struck off the Trade Register and the Patent Roll, and her buyer’s card has been withdrawn.”

Unable to work as a tailor or keep the store due to the anti-Jewish legislation, Peril worked from home for two companies: Victor Fabre, at 12 rue Marcadet, earning 550 francs a month, Mr. Menart (one of its employers) and Ballan[17], at 84 Boulevard Barbès. She also continued to work from home for private customers until one or more neighbors reported her in writing, complaining that they were being disturbed by “too many comings and goings, and customers who try the wrong door or the wrong floor”. In a report to his manager, Mr. Montovert de la Tour explained that he had “reiterated, orally and in writing, his formal warning to the Zanvil woman not to continue with these reprehensible activities” and that he had “informed Mr. Zanvil of the penalties to which his wife was risking by continuing to contravene the provisions of the German decrees”.

Haïm died at home, at the age of 48, on May 16, 1943.

7. The arrest and deportation

The Gestapo arrested Peril at her home on July 18, 1944. The doorkeeper, Mrs. Galtier, and a neighbor, Mrs. Cottard, confirmed that “the Germans” arrested her on the grounds that she was an “Israelite”, meaning that she was Jewish[18].

She was interned in Drancy transit camp until she was deported on July 31, 1944. She was murdered as soon as she arrived in Auschwitz on August 3, 1944.

After the war, in 1946, a Jancu Haimovici opened a case file on Peril Zanvil, claiming that he was her “brother-in-law”. Neither he nor his wife were actually related to Peril or Haïm, but he had been best man at Haïm’s first wedding. Might he have been in contact with Peril’s family, who asked him to find out what had happened to her? There are no records to shed any light on this.

Sources

[1] Georges Pérec, Ellis Island, P.O.L, 2015 (1980, 1st edition).

[2] Peril’s place of birth varies, depending on the record: Tzibana (marriage certificate), Jassy (Peril’s death certificate, issued in July 1962). It is the same for her date of birth.

[3] Carol Iancu, “Le pogrom de Iasi, 28-30 juin 1941, Histoire et mémoire” Témoigner. Entre histoire et mémoire, n°135 / October 2022.

[4] See Paris digital archives, 1918, town hall of the 18th district, act n°958.

[5] Sepi Posner was born in Galatz in Romania on February 21, 1900. Until she got married, she lived with her parents at 12 rue Coustou in the 18th district of Paris.

[6] Sépi and Haïm Zanvil’s marriage certificate dated May 23, 1918. Digitized Archives of Paris, 18th district, act n°958. Haïm and Sepi were divorce on July 5, 1920.

[7] These details are mentioned in the confiscation report: “Small store, with storeroom at the back converted into a workshop, also used as a dining room and kitchen”, “Bespoke tailoring, garment alterations, etc… contact Madame Zanvil, 2nd floor, door on the right”. Aryanization dossier, Base ARYA, French National Archives at Pierrefitte, ref. AJ38/1735, dossier 995.

[8] These figures are taken from a paper by Philippe Boukara, La déportation de Juifs originaires de Iasi et de son judet à partir de la France, Iasy, 2021.

[9] Henri Morez (Hers Askenasi), L’air était saturé de peur, Cherche midi, 2015, p.67.

[10] Letter from Peril to her sister, 1929, Adrian Aresteanu, family archives.

[11] Id

[12] This was a pediatric hospital.

[13] Letter dated March 30, 1935, from Peril Zanvil to Aron Berkovi, Iassy, Adrian Aresteanu, family archives

[14] Application for French citizenship by naturalization, 16043X14, French National Archives in Pierrefitte.

[15] Letter dated March 30, 1935, from Peril Zanvil to Aron Berkovi, Iassy, Adrian Aresteanu, family archives.

[16] Aryanization dossier, Base ARYA, French National Archives at Pierrefitte, AJ38/1735, dossier 995.

[17] Id

[18] DAVCC (Victims of Contemporary Conflicts Archives Division of the Ministry of Defense Historical Service) dossier n°21P276317

Français

Français Polski

Polski