Victor ALGAZI

Photo of Victor and his sisters

We are a group of 9th grade students who are involved in a memorial project in collaboration with Convoy 77, a association that works to preserve the memory of the people who were deported on this convoy, which left Drancy on 31 July 1944. We are going to focus on Victor Algazi, who was one of the victims. We based our work on documents provided by Convoy 77 and also on the books and videos that we studied during the year.

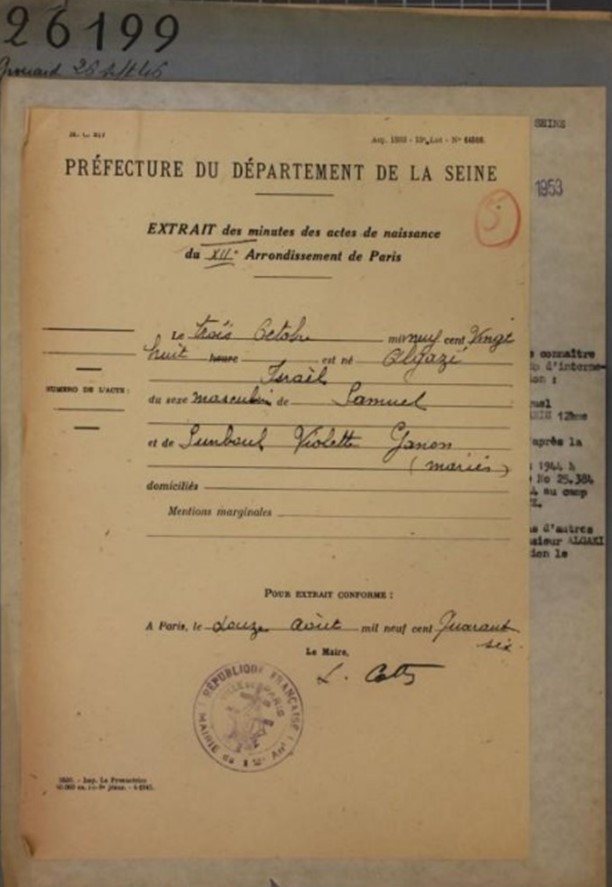

My name is Israël Victor Algazi. I was born on October 3, 1928 in the 12th district of Paris, at 22 rue de Lutèce to be exact. My birth certificate was issued in Paris on November 06, 1951 in the same district. I was therefore a French citizen. My parents, Samuel Algazi and Violette Sunboul Ganon, were married. We lived together at 20 rue Lamartine in the 9th district of Paris. I had an older sister , whose original name was Zelma and who was born on September 20, 1927, and a younger sister, Huguette, who was born on February 2, 1930. Sadly, my mother died just after she was born.

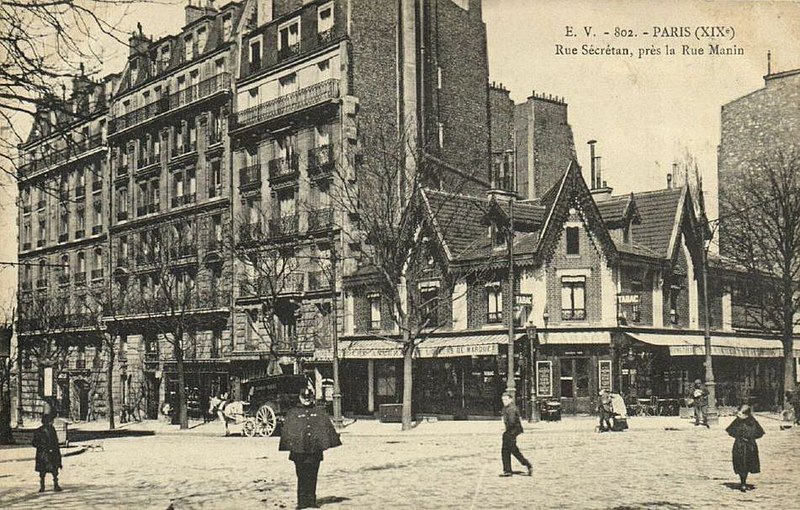

Map showing the location of the 19th district of Paris

I had a fairly typical childhood: I went to school, I had plenty of friends and I had a lot of fun, but I also missed my mother because I never really got to know her. I was 11 years old when the war began and 12 years old in May 1940, when the Germans attacked and occupied France. Then, in June, Marshal Pétain signed the armistice and decided to collaborate with the Germans. In October 1940, a law on the status of Jews was passed, which meant that we were banned from visiting parks, some shops and cinemas etc. The Jews also had to take part in a census and were put on a register.

I was 13 years old when the first round-ups began. Some Jews from our neighborhood were arrested and never seen again. When I turned 14, I had to wear a yellow star sewn onto my clothes whenever I went out. Even though we were still children, we soon realized that we were considered inferior to the rest of the population. My sisters and I then went to live in a children’s home. My father placed us there. I have only very vague memories of it, but he must have intended to protect us, because who would have thought that we would be taken away? It also meant that he could keep himself hidden more easily. The children’s homes were run by the U.G.I.F. (Union Générale des Israélites de France, or General Union of French Jews). The first home was on the rue de Secrétan in the Seine department, but we moved quite often as a result of the bombings and we ended up at the Lucien de Hirsch school. This was the oldest Jewish school in France, and 125 children and 52 adults were living there at the time.

The Lucien-de-Hirsch school

When I was 15, I was arrested at the Lucien de Hirsch school in Villejuif and then sent to Drancy, together with my sisters. We were arrested in the middle of the night: we were fast asleep, and although we didn’t really understand what was happening to us, we felt sure that they hadn’t come for us for our own good! We were in our pajamas and we had barely enough time to grab a few of our belongings!

According to his arrest record, Victor was interned in Drancy from July 22, 1944 to July 30 of the same year. He was one of the 300 or so children rounded up that night from the various U.G.I.F. orphanages, of which there were six in total. Drancy was a transit camp in which most of the Jews in France were gathered before being deported. This huge four-story U-shaped building had served as a prison before the deportations began. The Jews were placed in different sections of the camp prior to their deportation; the closer the section was to the gate, the sooner they were scheduled to leave. The camp was surrounded by a double row of barbed wire. A dozen stairways led to the upper floors and the toilets were in a building built of brick. The main building surrounded a courtyard about 200 yards long and 40 yards wide.

Drancy camp

When we arrived in Drancy, we were asked to hand in all our papers, jewelry, valuables and cash, but I had none to give them. The accommodation was terrible. There were no beds, the sanitation was awful and there was not enough food. We were only allowed a small ration of bread and even that not every day. We were starving and Huguette complained a lot because she was so hungry. Sickness was rife and we could only wash ourselves occasionally. The older children took care of the younger ones. We just waited. I stayed there until July 31, 1944.

First of all, we were put on buses to the Bobigny railroad station. There was a deathly silence; no one dared to speak. Once we arrived, they made us get into cattle cars. The doors were high up, so it was hard to climb in. It was a dangerous ordeal for the seniors and the mothers who were deported with their children. There were about sixty of us in each car, all carrying a bag of some sort. There was not enough room to sit down, so we had to stand up and take turns sitting down for the whole trip. We had no food or drink either. We only had a kind of bucket in which to relieve ourselves. It soon filled up and the smell was unbearable. On top of that, it was incredibly embarrassing; we felt ashamed and humiliated. It was unbearably hot and we didn’t even know where we were going. The journey lasted almost three days and three nights.

Cattle cars

When we arrived in Auschwitz, they asked us if we were tired. If we were, we were told to get into a truck. The seniors, the mothers, the children and some other people got in and were taken away.

I got separated from my sisters who both stayed behind because they separated the boys from the girls. I didn’t see them after that and I cried because I was all alone. The guards made us leave our bags on the train. We walked a long way towards the camp. We could hear screaming, yelling and barking.

I went with a large group of people to some strange place. We then went into a shower room where the guards told us to get undressed.

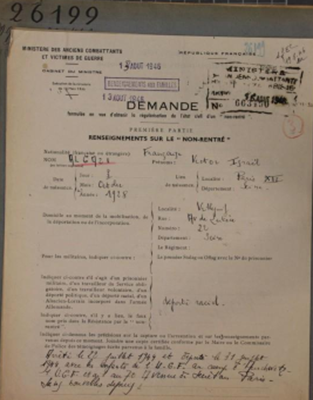

Victor was officially declared to have died on August 5, 1944 in the Auschwitz camp, the same day as his sister, Huguette. He must not have looked old enough to be selected for forced labor. His death certificate was issued to his father on January 14, 1948 (file 26.199, compiled in the 7th district of Paris). A request for information on Victor was made on June 1, 1953 to the office of files and research in order to have him recognized as having been deported on grounds of race. The response was delivered on July 27 of the same year. It should be noted that he was initially listed as having “died at Drancy”. Subsequently, on March 20, 1954, he was awarded the title of “political deportee”. A notification of indemnity payment was issued on March 14, 1955. Since he had no children, the beneficiaries were his ascendants and they were awarded 12,000 French francs.

Yvette, the only family member who survived after having been deported on this convoy, died much later, on December 27, 2017, at the age of 90.

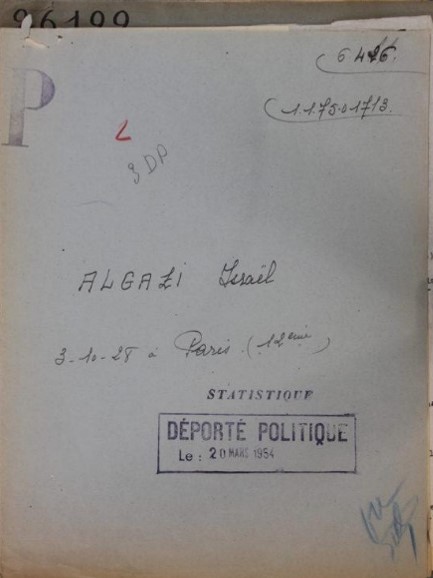

Blue record card stamped with the words “déporté politique”, meaning “political deportee”

Victor’s birth certificate

“Non-returned person” information sheet

Sources

- Archived records provided by Convoy 77

- Testimonials of Béqui Pisanti, Marceline Loridan and Yvette Levi, which are available on the Shoah Memorial website

- Books by Simone Veil, Jeunesse au temps de la Shoah ; Ginette Kolinka, Retour à Birkenau; Henri Borlant, Merci d’avoir survécu and Ida Grinspan, J’ai pas pleuré

- Photo taken at the Shoah Memorial at Drancy

Français

Français Polski

Polski