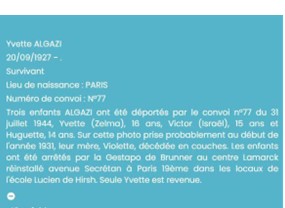

Yvette ALGAZI

We are a group of 9th graders from Les Blés D’Or middle school in the Seine-et-Marne department of France, and we participated in the Convoy 77 project in order to write the biography of Yvette Algazi. We worked with archived records and drew on what we learned on our field trips to Drancy, in museums during our trip to Berlin and from the many testimonies we studied, as well as from documentation about the Holocaust and books we read, such as Simone Veil’s Une jeunesse au temps de la Shoah (Growing up at the time of the Holocaust).

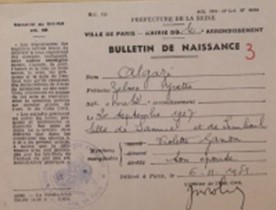

I am Yvette Zelma Algazi and I was born in the 12th district of Paris on September 20, 1927. My family and I were Jewish. My mother was called Violette Ganon, but I did not know her for very long because she died giving birth to my sister when I was three years old. My father, Samuel Algazi, was born on July 31, 1906, in Turkey. He emigrated from his country due to the Greco-Turkish war, 1919-1922.

Bulletin de naissance

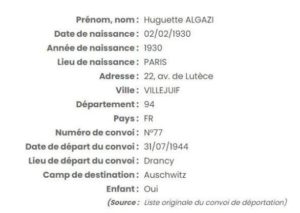

My brother, Victor, was born a year after me, on October 3, 1928 and my sister, Huguette, was born on September 2, 1930. Still a child, I was placed in a Jewish children’s home at 2 avenue de Lutèce in Villejuif.

Information about Huguette and Victor from the Shoah Memorial

I had a happy childhood, and I had a lot of fun with my brothers and sisters since we were almost the same age. My father worked hard to provide for us. When he was at home, he spent his time playing with us. We loved him very much. We also had a nice nanny to take care of us and we were very fond of her too.

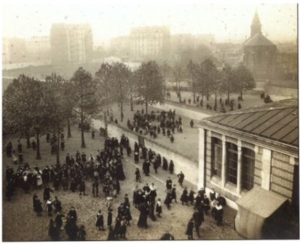

In 1939, when I was 12 years old, I heard about the invasion of Poland and the beginning of the Second World War. I was very worried and afraid of what might happen to us. My father then enlisted as a volunteer in the Régiment de Marche de Volontaires Etrangers, or Infantry Regiment of Foreign Volunteers (RMVE). Huguette, Victor and I were therefore sent to stay in a children’s home, the Rothschild orphanage.

The Rothschild orphanage at 15 rue Lamblardie

Three years later, in 1942, it became compulsory to wear a Jewish yellow star. I could feel people staring at me and I felt ashamed. No one saw me as a young girl anymore, just as a Jew, so I no longer dared to go out. Ever more anti-Semitic laws were passed. We couldn’t even go out when we wanted to, because a law dated February 7, 1942 forbade us to be out from 8 pm to 6 am. On July 8, 1942, we were even forbidden to go to the shops except between 3 and 4 pm.

Just as I was losing hope, the Allied landings on June 6, 1944 were a great source of relief. I once again believed that the war would soon be over, but around 1 a.m. on the night of July 21-22, 1944, Huguette, Victor and I were arrested by Brunner’s Gestapo men. There were a lot of children and a few adults, since they arrested everyone in the orphanage. We were all taken to the Lucien de Hirsh School. It was really frightening. I hoped that nothing would happen to my brother and sister, who also looked terrified. I kept thinking about my father, who must have been very worried.

The Lucien de Hirsh school, in the 19th district of Paris

We were then sent to Drancy, on foot. At that time I was nearly 17 years old. I was terribly afraid, but I tried not to show it so as not to worry the young children. It was a long way and we had hardly any belongings with us.

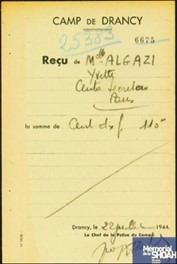

I stayed in Drancy for several days, from July 22 to 31. When I arrived, they confiscated the 110 francs I had brought with me. They told me they would give it back to me at the end of my stay but that was a lie. We had very little to eat except for a little soup. The toilets were outside the building and we were only allowed to wash ourselves once a week. During the day there was nothing to do, so it was quite boring. There were guards watching us all the time, which I felt a little embarrassing at times. I had to move rooms frequently, because the room I was in depended on the number of days left before my departure date.

Drancy camp

Drancy internment record

Early in the morning on July 31, we were taken by bus to Bobigny railroad station. Soon afterwards, we were loaded into cattle cars. We had nothing to eat or drink. Since it was summer, it was extremely hot, and we were all crammed in together. You could hear people screaming and crying, which I found atrocious. The whole car smelled terrible because we had to relieve ourselves in it and we were sweating in the heat. It was really horrible. I couldn’t even sit on the straw that covered the floor; there was not enough room, because there were too many of us. The journey took three days and two nights, which seemed such a long time. My brother and sister and I were in the same car, so that reassured me a little.

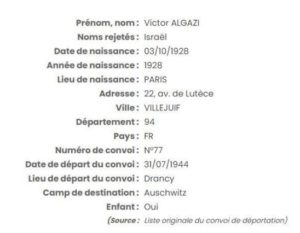

Certificate

I arrived early in the morning on August 4. A foul smell was noticeable from the moment we arrived. We could hear the SS men yelling and the dogs barking. I was able to turn around for a second and saw some people lying dead in the wagon. I didn’t have time to take in the horror of it because they pushed me into a line. I had to wait for a long time, not understanding what was going on, but when I heard the guards talking, I understood that I was in Auschwitz Birkenau. They had separated me from Victor and Huguette, so I was very worried about them.

They asked me how old I was, so I said that I was 18 because I wanted to seem older. Someone on the platform had advised me to do this. They took all my things and sent me off to be disinfected. We were all naked and felt extremely embarrassed as we stood there in front of the guards, who were staring at us; it was terribly humiliating. I took a disinfectant shower, was shaved all over and then had a number tattooed on my arm. After all that, I was sent into the camp, where I was sent to work the very next day. I couldn’t understand why they treated us so callously., even the animals were treated better than us. My clothes were worn out rags and not my size. With our hair shaved off, we looked like nothing on earth.

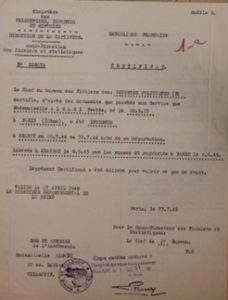

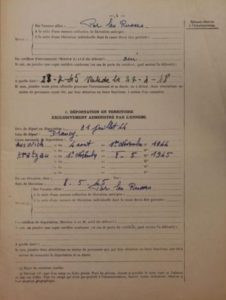

Yvette’s deportation record

I was forced to work in appalling conditions. Many of the prisoners in the camp were beaten to death by the SS. Food and water were always scarce and the poor sanitary facilities meant that even small wounds became infected.

Every day, there was a great deal of violence; we could hear the sound of gunfire within the camp. Guards came to inspect the state of the camp and checked our identity in the morning and in the evening after work by making interminable roll calls. The days were exhausting and we only had soup and a little bread to eat despite having to walk a long way to do forced labor. I found it hard to accept that this nightmare was reality and my health deteriorated significantly due to the poor living conditions.

On November 1, 1944, I was taken to work in Kratzau, a subcamp of the Gross-Rosen camp. Again, the journey was atrocious. People died before my very eyes; it was horrendous. The camp was overcrowded, the work days were over 12 hours long and there were at least four roll calls a day to check our identity. Again there was a lack of food and living conditions were unhealthy. Some people looked like skeletons and were very sick. The guards were violent and gave beatings and punishments. Our life expectancy was very short at that time, but the desperation nearly killed us too. The camp was made up of ruins, with some buildings made of bricks and wood. There were also gas chambers there.

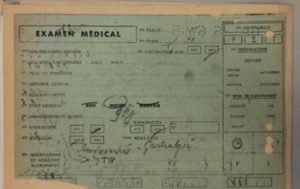

I was liberated by the Russians on March 8, 1945. I spent some time in hospital with some other Jews and then I was repatriated to Paris on June 6, 1945. In all, I had lost 20 pounds. It was a great relief to be home. I also had a very bad stomach ache and digestive problems.

Medical examination report

I wondered where Victor and Huguette were, so I did some research to try to find them. Unfortunately, I found out that they had been killed by the Germans. What I lived through was horrible and I held on to those painful memories no matter how hard I tried to forget.

Yvette Algazi died in Vence, France, on December 27, 2017.

Sources

- Archived records provided by Convoy 77

- Testimonials of Béqui Pisanti, Marceline Loridan and Yvette Levi, which are available on the Shoah Memorial website

- Books by Simone Veil, Jeunesse au temps de la Shoah ; Ginette Kolinka, Retour à Birkenau; Henri Borlant, Merci d’avoir survécu and Ida Grinspan, J’ai pas pleuré

Français

Français Polski

Polski