Louise MOCHON

We began working on the Convoy 77 project towards the end of February, 2024. For many of us, the project provided an introduction to the world of historical research. It was a memorable experience, and although we had various setbacks along the way, we did eventually manage to find out what had become of Louise Mochon and her family. The Holocaust featured prominently in our school curriculum this year, in geopolitics and history classes as well as in humanities and literature. By working on the biography of a deported person, we were able to take an in-depth look at what deportation means, and to explore it from a far less academic perspective. Writing such a biography also helps to maintain the legacy of what happened during the Holocaust. Very few former deportees are still alive, and we were very lucky to be able to find Louise. We know that bearing witness remains both difficult and painful for the last remaining concentration camp survivors. We would like to thank Catherine Koblentz for providing us with so much detailed information about her mother. We hope that our work will help to preserve the family’s memories of Louise.

As far as our approach to the work and the research is concerned, we shared out the various tasks to be carried out. Each of us took turns to find information about a period in Louise’s life and add it to the biography. We went to Rue Sedaine, in Paris, to see the places where the Mochon family lived before, during and after the war and to look for any remaining traces of their time there. These long forays through the streets of Paris in search of places where Louise might have lived often proved unsuccessful, however. When we began our research, we were able to draw on the records provided by the Convoy 77 team, which mainly involved administrative procedures for deportees who survived. In addition to these records, we also found the Mochon family’s Drancy files in the French national archives in Pierrefitte, which enabled us to explore the steps involved in the deportation of each member of the family. Secondly, we searched the Bad Arolsen archives at the International Center on Nazi Persecution[1], which was set up by the International Committee of the Red Cross in Germany at the end of the Second World War. The records they shared with us turned out to be a decisive factor in our search for Louise Mochon. We already knew that she had survived and returned to France, and a number of official documents confirmed that she had applied for compensation, but apart from that, there was no trace of her. However, we discovered from the Arolsen archives[2] that she had got married in 1959, and another record[3] mentioned that Serge Klarsfeld’s team had contacted her in 1996 as part of their research for his book “Mémorial des enfants juifs déportés de France” (French Children of the Holocaust: A Memorial). The town hall of the 19th district of Paris had responded to the Arolsen archives service confirming that it had forwarded the request to the person concerned. We therefore concluded that Louise Mochon, née Koblentz, was still alive in 1997, but other than that, all our research was in vain; we found no trace of her. We then had to begin a meticulous investigation in the Paris Archives, and little by little, through birth and death certificate extracts, searches of school registers and even cemetery records, we managed to uncover some clues about Louise’s family. The decisive factor was being able to identify her husband, Albert Koblentz, because his death certificate gave an address in the 18th district of Paris. We went there, but the group of buildings was too spread out to even contemplate going from door to door. Besides, time was passing and we had to think about finalizing our project. At the end of May, after discussing it with our teacher, we decided to send a letter to the address on the death certificate, hoping that, if Louise was still alive (and there was no reason to think otherwise, as we had checked the French National Institute of Statistics and Economic Studies death registers going back to 1990 and had found no trace of Louise’s death), we might get a reply. Essentially, the letter was a last-ditch attempt, so we explained in a straightforward manner who we were and that we were writing a biography, her biography, as part of the Convoy 77 project. And then, one evening, we were thrilled when the student who had given his number received a call from Louise’s daughter, Catherine, who told us that Louise was still alive! She agreed to send us a huge amount of information, including a number of photographs, although she made it clear that her mother was still unwilling to talk about this painful chapter of her past. Our work then took a new turn, as we received a number of key documents that shed much-needed light on various points that had hitherto remained unclear.

The biography of Louise Mochon, who was deported at the age of 16, not only includes details about her family and her husband, but also provides a chilling account of what the European Jews endured at the hands of the Nazis, who were so ruthlessly determined to stamp them out.

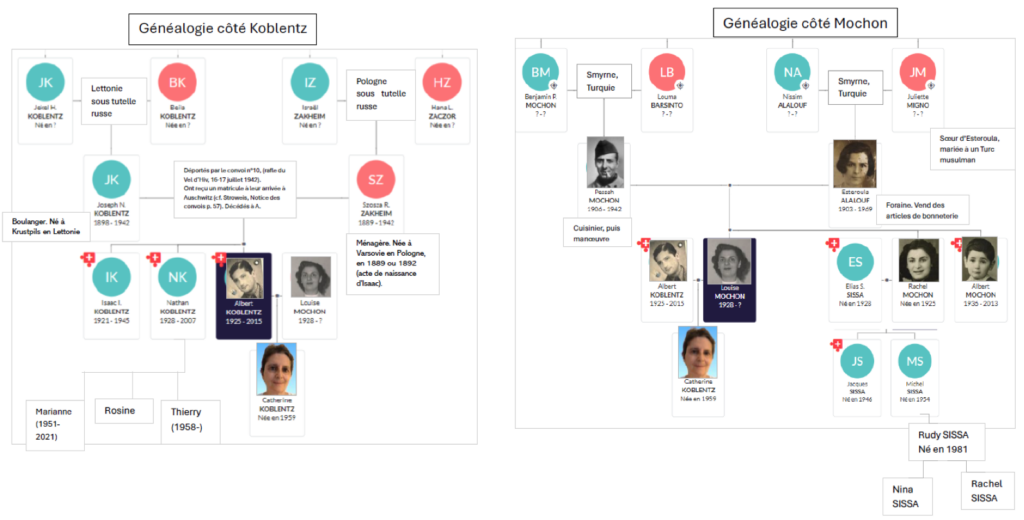

Louise’s parents were Pessah Mochon and Esteroula Alalouf. She had an older sister, Rachel, and a younger brother, Albert.

She went on to marry Albert Koblentz, who was also deported to Auschwitz-Birkenau (as were his parents and his older brother, while his younger brother joined the FFI resistance group).

Louise and Albert had one daughter, Catherine Koblentz.

Chronology

- January 1, 1903: birth of Esteroula/Steroula Alalouf in Smyrne/Izmir, in Turkey.

- January 15, 1906: birth of Pessah/Elie Mochon in Tiré in the province of Smyrne/Izmir, in Turkey.

- December 7, 1925: birth of Rachel Mochon.

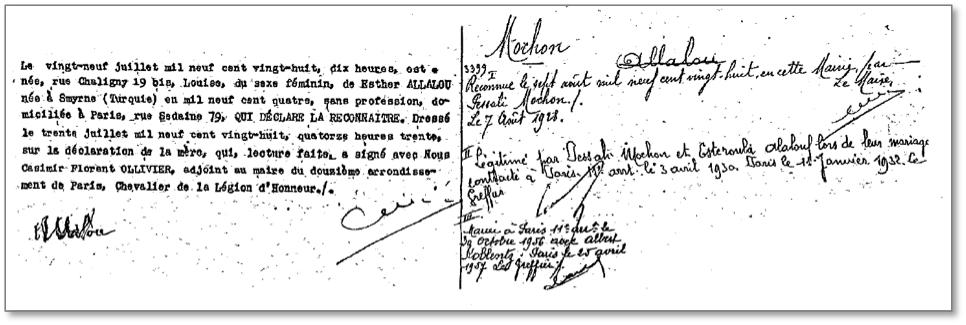

- July 29, 1928: birth of Louise Mochon at 10:00 am at 16 bis rue Chaligny in the 12th district of Paris (Saint-Antoine Hospital).

- April 3, 1930: marriage of Pessah and Steroula Mochon at 11 :43am in the town hall of the 11th district of Paris, which means that their daughters were legitimate.

- April 19, 1936: birth of Albert Mochon.

- September 1939-June 1940: Pessah enlisted as a volunteer in the RMVE (Foreign Volunteers Infantry Regiment).

- June 30, 1941: Esteroula, a traveling saleswoman, ran out of goods to sell.

- July 7, 1942: the end of a legal procedure brought by the French government, Esteroula was struck off the commercial register.

- July 1942: Louise and her family had to pick up their yellow stars.

- July 16 -17, 1942: Joseph and Szosza Koblentz[4], Albert’s parents, were arrested during the Vel d’Hiv roundup[5].

- End July/August 1942: Pessah was arrested during an identity check a few weeks after the Velodrome d’Hiver roundup, as he was on his way to work[6].

- July 24, 1942: J. and S. Koblentz were deported on Convoy 10 to Auschwitz-Birkenau[7].

- September 14, 1942: Pessah was deported from Drancy to Auschwitz-Birkenau on Convoy 32. According to the information gathered by Louise and her family, her father died very shortly before the camp was liberated. Pessah therefore appears to have been selected to go into the camp to work and to have survived two years of living hell in Auschwitz-Birkenau.

- August 18, 1943: The Koblentz siblings Isaac (22), Albert (18) and Nathan (15) arrived in Tarbes, in the Hautes-Pyrénées department of France, and registered with the local Refugees’ Service[8].

- August 21, 1943: The STO (compulsory work program) summoned Albert and Isaac to work as laborers at an industrial plant, Ets. Dumont, in Tarbes.

- October 18, 1943: Albert and Isaac began work a factory belonging to the aeronautics company Ets. Morane-Saulnier in Louey in the Hautes-Pyrénées department, and Nathan worked for a photographer[9].

- November 6, 1943: Having asked the Refugees’ Service for help, each of them were given a pair of trousers and a shirt.

- April 8, 1944: Esteroula Mochon and his oldest daughter, Rachel, were arrested and interned in Drancy camp. Albert, the youngest sibling, who was 8 years old, was staying in hiding elsewhere in the country, and Louise, who was 15 years old and working as a chambermaid in a hospital, were not arrested.

- April 29, 1944: Esteroula and Rachel were deported from Drancy to Auschwitz-Birkenau on Convoy 72.

- May 1, 1944: Convoy 72 arrived in Auschwitz-Birkenau. Esteroula and Rachel were selected to enter the camp for forced labor[10].

- During the night of 21 to 22 July 1944: The roundup on rue Vauquelin took place. Louise was arrested in the UGIF children’s home at 9 rue Vauquelin in the 5th district of Paris, together with thirty or so other young Jewish girls.

- Isaac and Albert Koblentz were arrested and deported to Auschwitz on Convoy 76. When they arrived, they were selected to go into the Monowitz camp for forced labor.

- July 31, 1944: Convoy 77 left Bobigny station, near Drancy, bound for Auschwitz-Birkenau. 1306 prisoners were on board, including 324 and a newborn baby, who had been born in Drancy.

- August 3, 1944: Convoy 77 arrived in Auschwitz-Birkenau.

- October/November 1944: Louise, Rachel and Esteroula were transferred to the Bergen-Belsen camp. It was only when they got to Bergen-Belsen that they met up with each other again.

- January 18, 1945: Isaac Koblentz was forced to take part in a death march heading for Gleiwitz, but died along the way. Albert meanwhile, who was very ill and unable to walk, was left behind in Monowitz.

- January 27, 1945: The Soviet army liberated the Auschwitz-Birkenau-Monowitz camp complex.

- April 15, 1945: The British army liberated the Bergen-Belsen camp, and found nearly 60,000 people there.

- May 17, 1945: Louise and Rachel’s record cards both state they returned to France by truck. However, Louise remembers being repatriated by train, together with her mother. Perhaps the girls insisted that they not be separated from their mother, whose state of health was such that she would have been too uncomfortable in a truck[11].

- May 21, 1945: Due to outbreaks of typhus, typhoid fever, tuberculosis and dysentery, the British troops decided to burn part of the Bergen-Belsen camp.

- May 24, 1945: Louise arrived at the repatriation center in the Lutetia Hotel in Paris, where she was issued card no.I.625.585[12]. Louise, Rachel and Esteroula stayed in the Lutetia center for three weeks. They then met up with young Albert, who had been kept hidden in the countryside during the war.

- September 25, 1945: Louise received her deported person’s card, type A.

- July 11, 1946: Rachel Mochon married Elias Sissa at 10 :13am at the town hall in the 11th district of Paris.

- October 6 and then November 15, 1950: Official recognition that Pessah Mochon had died during deportation.

- March 11, 1952: Louise applied for the status of “déporté politique” (political deportee, meaning that she had been deported for political reasons).

- May 9, 1955: Louise was officially granted the status of political deportee (she was listed as living at 79 rue Sedaine, in the 11th district of Paris, although the number 79 may be a mistake, because in October she was living at no. 77).

- October 5, 1955: Louise received the deportees’ allowance of 12,000 francs.

- October 30, 1956: Louise Mochon married Albert Koblentz in the town hall of the 11th district of Paris.

- July 24, 1959: Birth of Catherine Koblentz, Louise and Albert’s daughter

- 1959: Louise and Albert were living at 8 impasse Kuszner in the 19th district of Paris.

- January 29, 1969: Esteroula Mochon died at 184 rue Saint Antoine[13]

- April 19, 1996: A French decree was issued that said that the words “died during deportation” should be added to death certificates. Pessah was one of the people to whom this applied [14].

- March 1997: The International Tracing Service at Arolsen contacted the town hall of the 19th district, following up on Serge Klarsfeld’s request. He was trying to track down the children deported during the Holocaust, and wanted to make contact with Louise.

- June 1997: The town hall of the 19th district replied to the ITS at Arolsen saying that they had forwarded the request to Louise Koblentz, but without giving her new address.

- November 3, 2013: Death of Albert Mochon, who was living at 17 avenue Vivien in Saint-Mandé, in the Val-de-Marne department of France[15].

- July 22, 2015: Death of Albert Koblentz, who was living at 234 rue Championnet in the 18th district of Paris[16].

Biography

Louise’s parents: before the war

Louise Mochon was born into a Turkish Jewish family. Her mother, Esteroula, Steroula/Steroula or Esther (H)alalouf, was born in Izmir (then Smyrna) in Turkey in 1903[17] and her father, Pessah or Elie Mochon was born in Tiré, also in the province of Izmir, on January 15, 1906. They emigrated to France sometime between 1919 and 1925. A number of historical factors prompted Turkish Jews to leave their country and move to France in the early 20th century. First of all, as the Young Turks movement gained ground in the Ottoman Empire, plans to make the country more “Turkish” gave rise to a new wave of anti-Semitism and animosity towards the Jewish community. As well as this, minorities were persecuted, an example of which was the Armenian genocide in 1915-1916. The First World War not only irreparably damaged the Ottoman Empire but also created a huge demand for labor in France, which needed to boost its economy and repair the damage caused during the war. This combination of circumstances triggered a wave of migration to France. Pessah, who had trained as a cook, emigrated in order to avoid a long period of compulsory national service. Esteroula, meanwhile, had a French friend in Turkey who helped her to leave the country and find a place in Paris, where she earned her living as a seamstress. Her mother had also been a seamstress. Having lost her parents at an early age, she most likely emigrated for financial reasons. We know that she had a sister who she corresponded with for a time in Judeo-Spanish, with the help of Rachel, her eldest daughter, because she herself was unable to read or write. After a while, however, due to the distance and the war, they lost touch. The fact that Esteroula’s sister married a Turkish Muslim man probably had something to do with it as well, as Jewish families frowned upon mixed marriages.

Pessah and Esteroula met in a restaurant, where Pessah was working as a cook. Soon afterwards, they set up home together at 7 Passage Maurice, in the 11th district of Paris[18].

Rachel Mochon, their eldest child, was born on December 7, 1925 in Paris, and three years later her little sister, Louise, was born at 10 a.m. on July 29, 1928, at 16 bis rue Chaligny, in the 12th district of Paris.

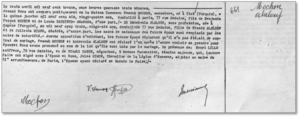

Louise Mochon’s birth certificate

Paris digital archives.

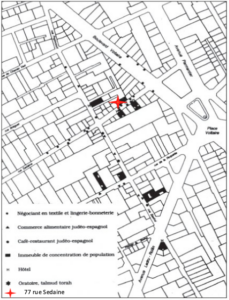

In 1928, the Mochon family was living at 79 Rue Sedaine, a street that was home to a large number of Jews from the East, so much so that the neighborhood was known as “Little Turkey.” In April 1930, according to Pessah and Esteroula’s marriage certificate, they had moved next door to 77 Rue Sedaine.

Plan taken from Annie Beneviste’s paper “Récits de migration, récits de persécution. La ‘petite Turkey’ entre mémoire et fiction” (“Stories of migration, stories of persecution. ‘Little Turkey’ between memory and fiction”).

Archives Juives, 2009 / 2 (Vol. 42), pp. 41-56. DOI: https://doi.org/10.3917/aj.422.0041.

Source: shs.cairn.info

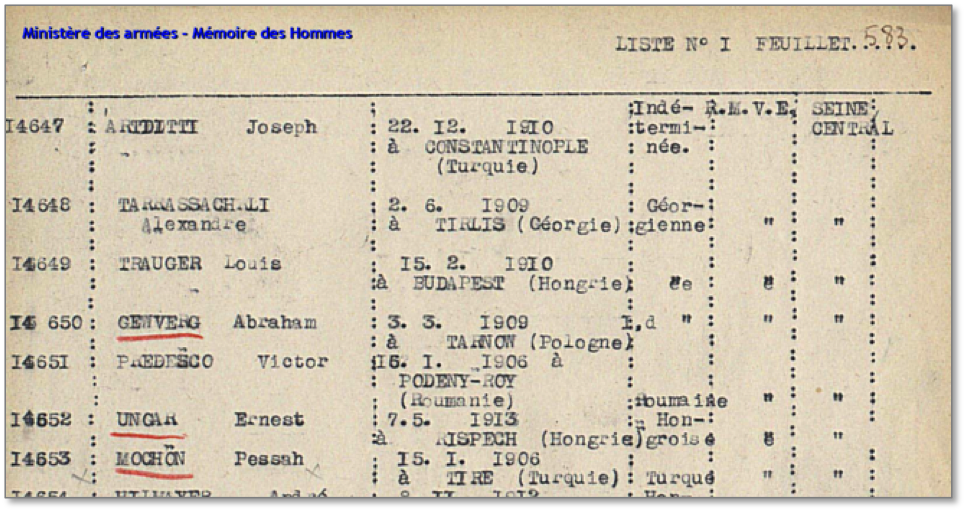

In 1927, in order to make it easier for foreign workers to integrate into French society, the government introduced a law that allowed them become naturalized as French citizens after having lived in the country for only three years[19]. Pessah Mochon does not appear to have requested French citizenship, however. Firstly, we were unable to find a polling card in his name in the Paris archives. Secondly, early on in the war, he joined the Foreign Volunteers Infantry Regiment[20] (his name is on the list below). Thirdly, on his Drancy internment card, it says “nationality: Turkish”[21] and lastly, Esteroula, when she returned home after the war, was not entitled to an invalidity card in the same way as Louise, Rachel and Albert Koblentz were, even though people who had been “denaturalized”, (i.e. had their French citizenship revoked) in 1940[22] had it reinstated in 1945[23]. Also, children born in France to foreign parents automatically became French at birth, although they could renounce their French nationality before they came of age if they wished. This meant that Louise and Rachel, who were both under 21 when they were arrested, were still French citizens[24].

Pessah Mochon is named on the Foreign Volunteers Infantry Regiment list. Mémoire des Hommes website, dossier 7_0085.

Pessah and Esteroula’s wedding photo, April 3, 1930.

(Koblentz family archives)

Photo of Pessah in uniform, taken sometime between September 1, 1939 and June 25, 1940. (Koblentz family archives). Foreign Volunteers Infantry Regiment, 1st bureau. First military region, Central Seine bureau, regimental number 14653.

Pessah and Esteroula’s marriage certificate. Paris digital archives

Esteroula and Pessah Mochon in 1930 (Koblentz family archives).

It was due to France’s need for workers that Steroula/Esteroula became a travelling hosiery saleswomen[25] in Paris, while Pessah began working as a laborer.

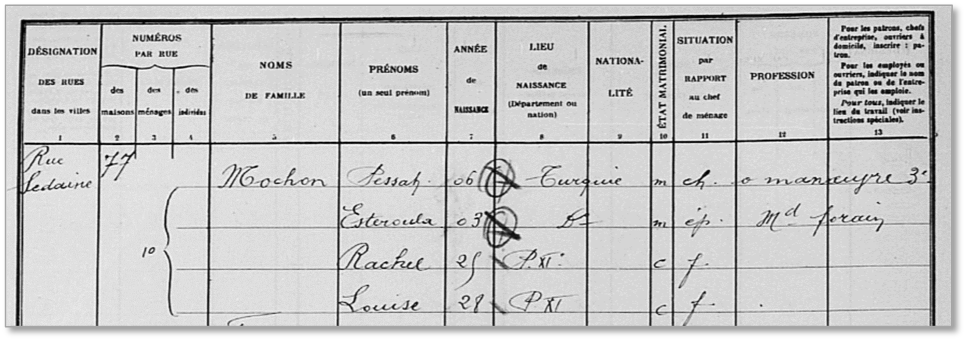

Extract from the 1931 census of 77, rue Sedaine, showing the Mochon family members.

Paris digital archives.

Rachel went to school on rue Keller[26] while Louise remembers going to school on rue Breguet. Louise’s Drancy internment card states that she was an apprentice seamstress, and Rachel’s states that she was a “mechanic”[27].

Albert, the last of the Mochon sibings, was born on April 19, 1936.

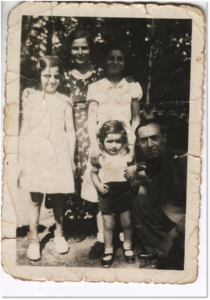

The Mochon family before the war. Left to right: Louise, Esteroula, Rachel, Albert

and Pessah. (Koblentz family archives)

Louise’s family during the war

We know from the French military records that Pessah volunteered to fight for France, even though he was not a French citizen. Louise remembers that at around the same time, as the Germans were advancing towards Paris, the family (presumably without Pessah) left the city for a short while, but soon moved back again.

When Germany invaded France on June 22, 1940, life took a sudden turn for the worse for Jews. On July 10, 1944, a few days after the German forces took over, the Vichy government was formed, led by Marshal Pétain. From the outset, the Vichy regime began collaborating with the Nazis by introducing a series of anti-Semitic laws. These banned Jews from practicing various professions and holding State positions, and gradually restricted their rights and freedoms even more.

The first decree on the status of the Jews was enacted on October 1, 1940. On October 2 and 3, the prefectures, by means of newspaper announcements and posters, asked both foreign and French Jews to register with the authorities. Louise’s parents were foreign Jews, but the children had been French from birth, which perhaps explains why the parents were not overly concerned about the negative impact this might have on their family. However, Louise later told her daughter that when the French government asked Jews to take part in the census, a member of the town hall staff advised them not to, as the surname “Mochon” sounded neutral and typically French, with no Jewish connotations. Even so, along with most other Jews who trusted the French state, the Mochon family went ahead and registered themselves[28].

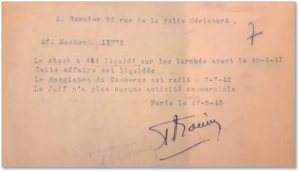

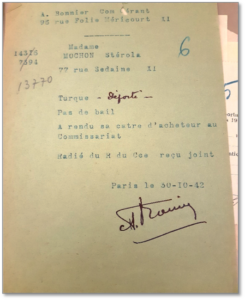

The second decree on the status of the Jews, enacted on June 2, 1941, was wide-ranging in scope and included a ban on Jews working in all commercial and industrial occupations. As a result, the Vichy authorities soon took an interest in Esteroula Mochon, who sold hosiery at fairs and on the markets. The records show that by June 30, 1941, when the confiscation process began, she had already sold off all her stock[29].

The administrator, who was appointed on July 7, 1941, then had Esteroula struck off the commercial register with effect from July 7, 1942. She was also ordered to return her buyer’s card to the police station by October 30, 1942, and not to engage in any commercial activity thereafter.

French National archives at Pierrefitte, n° 121418-Steroula Mochon.

French National archives at Pierrefitte, n° 121453-Steroula Mochon

French National archives at Pierrefitte, n° 121547-Steroula Mochon

That same year, on May 28, 1942, a decree was enacted that required all Jews over the age of six to wear the yellow star. Louise and her family collected theirs in July. 1942 was also the year in which the Nazis began deporting Jews from Drancy to concentration and extermination camps[30]. The deportation of French and foreign Jews quickly gathered pace and the number of convoys increased, and as a result, Louise’s father, Pessah Mochon, was arrested and deported. He was caught while on his way to work a few weeks after the Velodrome d’Hiver roundup, in either late July or early August 1942. He was deported on Convoy 32, which left Drancy on September 14, 1942, bound for Auschwitz-Birkenau. When the convoy of around 1000 foreign Jews arrived in Auschwitz, the selection process took place immediately: around a hundred people, 58 of whom were men, were assigned a registration number and sent into the camp to work, while the rest were sent straight to the gas chambers. Pessah, who had previously worked as a laborer, appears to have been one of the men selected for forced labor, as Louise and her family later discovered that he had died in Auschwitz shortly before the camp was liberated on January 27, 1945.

Esteroula, most likely soon after Pessah was arrested, decided to send Albert out of Paris to live in hiding in the countryside. She took him back later in the war because she missed him so much, but eventually sent him away again, and as a result he was not deported.

Given that Pessah had been arrested and Esteroula was no longer allowed to work, the family must have struggled to make ends meet, which may explain why Louise got a job at the hospital.

Less than two years later, in April 1944, Louise’s mother and her sister Rachel were also arrested: they were deported from Drancy to Auschwitz-Birkenau on Convoy 72 on April 29, 1944. Louise was working on the ward at the hospital at the time[31]. After they were deported, Louise, who was only 15, lived alone for around three months. Although she was reluctant at first, she eventually took the advice of a social worker and went to look around the UGIF (Union Générale des Israelites de France, or General Union of French Jews) home for girls on rue Vauquelin, in the 5th district of Paris. After her visit, she felt she would be more comfortable staying there, and she liked the fact that there was piano, so she moved in. She was still wary, however, and she and some other girls put together an escape plan, which they intended to use if ever the Germans ever came to arrest them.

From when Louise was rounded up on rue Vauquelin to her arrival in Auschwitz-Birkenau

The Vichy authorities founded the UGIF in 1941, at the request of the Nazis. It replaced all other Jewish organizations and was intended to monitor the whereabouts and activities of all the Jews in France. It also provided social and financial support to Jewish families and shelters for Jewish children. We thus assume that the UGIF took Louise in because she was an orphan, both of her parents having been deported.

The UGIF home at 5 rue Vauquelin, in the 5th district of Paris.

Louise was still living in the UGIF home on rue Vauquelin, run by Françoise Mortier, on July 20, 1944, when someone tried to assassinate Adolf Hitler. It was supposedly in retaliation for this attack that Aloïs Brunner, who was in charge of Drancy camp, had all the children in the UGIF homes in and around Paris arrested. During the night of Friday, July 21 to Saturday, July 22, 1944, the French police rounded up the children in rue Vauquelin. Louise was taken away in the middle of the night, along with 27 other young girls and 3 young women who worked there, before they had even had time to get dressed. Yvette Lévy, who was arrested at the same time as Louise, said that she and the other girls had to spend three days in Drancy in their nightdresses, after which the manager was allowed to go back to the shelter to collect some of the girls’ belongings. When Louise and the other girls arrived in Drancy, the Germans carried out a roll call: they already had a list of all the orphans whose parents had been deported. Living conditions in the Drancy camp were appalling, not only due to the buildings themselves, which were too hot and had no running water or sanitary facilities but also because there was so little food, and what there was made some people sick. To make matters worse, the officers in charge of the camp were abusive, including the commandant, Aloïs Brunner, who the deportees said was a cruel man who couldn’t bear to hear children laugh. On July 29, 1944, Louise turned 16.

In the early hours of Monday, July 31, 1944, 1,306 internees from Drancy were herded onto buses and taken to Bobigny station. There they were put on a train: this was Convoy 77.

The convoy was made up of 1306 people, including 250 children under 16 and a newborn baby. The deportees were first taken by bus from Drancy camp to Bobigny station, which was just a five-minute journey. When they arrived, they were crammed into cattle cars, in which there was not even room to sit or lie down. The wagons were overloaded with people, up to a hundred per car. There was little or no ventilation, which made it hard to breathe, especially with so many people trapped in a such a confined space. They had hardly any food or water during the journey, and many suffered from extreme dehydration and hunger. There were no toilets either, so they had to relieve themselves in buckets or in the corners of the wagons.

The route taken by Convoy 77 (Yad Vashem website).

At long last, during the night of Wednesday 2 to Thursday 3 August 1944, after an extremely arduous 70-hour journey, Louise and her friends from the UGIF home arrived in Birkenau. Meanwhile, back in France, the Allied troops were advancing in Normandy: the town of Vire, in the Calvados department of France was liberated on August 2, and General Patton landed in Dinan, in Brittany, on August 3.

Yvette Lévy, who was also rounded up in the UGIF home on rue Vauquelin and deported on the same convoy as Louise, later recalled the indescribable smell of burning flesh that hit them the moment they arrived as “a stench that caught in your throat”[32]. In fact, 2,996 gypsies had been murdered in the gas chambers the night before Convoy 77 arrived, and it was the smoke from their burning bodies that engulfed the deportees. As soon as they got off the train and onto the ramp, the selection process took place. The younger, fitter people, including Louise, were selected to go into the camp to work, while everyone else sent straight to the gas chambers and murdered. They did not know at the time, but the gypsies had been gassed the night before in order to make way for the “fresh” new workers.

Louise did not meet up with her mother and sister right away, but heard from other deportees that they were there somewhere. She eventually caught up with them when they were transferred from Birkenau to Bergen-Belsen in October or November 1944[33], nearly six months after she last saw them. The reason they were transferred in the fall of 1944 was because the Soviet troops were moving closer, so the Germans decided to send the deportees in Auschwitz-Birkenau to camps further away from the Eastern Front.

From the time Louise left Auschwitz-Birkenau until the Bergen-Belsen camp was liberated

Between late August and December 1944, and even in early January 1945, many women, particularly those who had been deported on Convoy 77, were transferred out of Auschwitz-Birkenau to other camps. Most of them were the younger women, as the Third Reich needed as many workers as possible to sustain the war effort. With the Soviet army closing in on them, the Nazis were keen to evacuate prisoners who were still fit enough to work and send them to other labor camps. The majority of the women were between 15 and 30 years old. Around 65,000 deportees were moved from the three main camps at Auschwitz-Birkenau to other camps. Louise was fortunate enough to be among the women who climbed aboard one of the last trains to Bergen-Belsen (as were her mother and sister), thus narrowly escaping being sent on the terrible death marches. She arrived in the Bergen-Belsen camp, south of Hamburg, in Germany, in October or November 1944, and it was there that she finally found her mother and sister. One of the first questions her mother asked her was if she knew what had happened to Albert. She knew that if he had been on the same transport as Louise, he would have been sent to the gas chambers immediately. Louise reassured her that when she left Drancy in July, he was still safe and living in hiding in the country[34]. In December 1944, Bergen-Belsen became one of the main camps to which prisoners from Auschwitz-Birkenau were evacuated. Between then and April 1945, however, 35,000 of the 85,000 of them died. Lisette Cohen, who was deported on Convoy 74, had previously lived on Rue Sedaine and knew Rachel Mochon, later recalled seeing Louise. She said that when she arrived in Bergen-Belsen having survived one of the terrible death marches, the three Mochon women helped her to find her mother, who had arrived earlier[35]. This is a good example of the solidarity between Jews from the rue Sedaine neighborhood, which remained strong even in the camps. On April 15, 1945, when the British army liberated the camp and the SS in surrendered, they found around 60,000 prisoners. However, there were terrible epidemics of typhus, typhoid fever, tuberculosis and dysentery throughout the camp, and the bodies of the victims were lying in the dirt. The British soldiers were horrified and hastily set up field hospitals.

Louise, together with her sister Rachel and her mother, Esteroula, was repatriated to France on May 17, 1945. Although some records say that they were brought home by truck[36], Louise clearly remembers that they travelled by train. To prevent further epidemics, the British army burned down the hospital barracks in Bergen-Belsen on May 21, 1945.

Louise, her sister and her mother arrived at the Lutetia Hotel reception center in Paris on May 24, 1945. During the Occupation, the building had been used as the German military intelligence service headquarters. Between April 26 and September 19, 1945, it was used as a reception center for survivors. When people first arrived, they were questioned about their time in the camps, disinfected with DDT, examined by a physician and X-rayed. They were also given a repatriation card as proof of identity, some clothes and shoes, subway tickets and a little money (1000 to 2000 francs). Sick people were sent to hospital or convalescent homes, while those who were too weak to go home or had nowhere to go stayed in one of the 500 or so hotel rooms for anything from a few hours to a few days, or even several weeks. Louise remembers that she, her mother and her sister stayed in the hotel for about three weeks, because someone was living in their apartment at 77 rue Sedaine, and it took a while to get them out. As for Albert, who had been kept hidden during the war, the family that was caring for him had to go to the Lutetia hotel and check the lists to see if any of his family members had come home. Albert was 9 years old by the time he was finally reunited with his mother and sisters.

Louise’s medical exam revealed that she was extremely weak. Her medical report states that she was suffering from dysentery, amenorrhea, cachexia (wasting syndrome), tooth decay, calcium deficiency, bone damage and pain, and cardiac insufficiency. Her overall state of health was described as “poor”[37]. She was also treated with the insecticide DDT (to eradicate lice, which are the most common carriers of typhus).

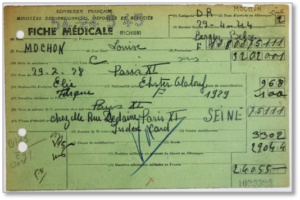

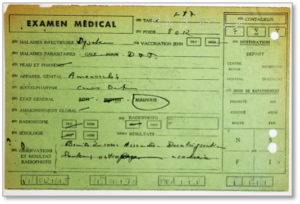

Louise Mochon’s medical report.

Victims of Contemporary Conflicts Archives Division of the Ministry of Defense Historical Service, in Caen, ref. AC 21 P 599256.

Louise was issued with a repatriation card, No. I. 625 585.

Louise’s life in Paris after the war

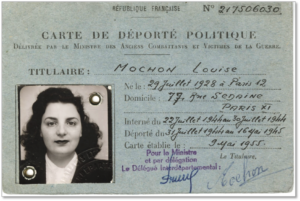

On September 25, 1945, Louise received a deportation certificate, type A, which was “issued to persons deported or interned by the enemy”[38].

This certificate entitled her apply for political deportee status (meaning that she was deported for political reasons), which she did on March 11, 1952. This was granted on May 9, 1955 and later that year, on October 5, she received a compensation payment of 12,000 francs (equivalent to around 300 dollars these days).

The Mochon family after the war. From left to right: Albert, Louise, Rachel and Esteroula.

Koblentz family archives.

On July 11, 1946, a year after they returned home from the camps, Louise’s sister Rachel married Elias Sissa, who was three years younger than her and lived at 5 bis boulevard de Bonne Nouvelle[39]. Rachel then worked as a secretary for a while before having two children, Jacques and Michel[40]. After that, she worked for a number of clothing manufacturers and then, together with her husband Elias, opened a market stall selling fabrics. Like her mother before her, she was an excellent seamstress, so was able to offer expert advice to her customers.

Another interesting point is that Esteroula and Rachel noted on Rachel’s marriage certificate that they did not know where Pessah Mochon was living, which implies that they had not yet given up hope that he was still alive. In fact, Pessah Mochon was not officially declared dead until November 15, 1950, and the date on which he died was modified in 1996.

Louise Mochon (center) with two colleagues in their workshop at the Bril factory in June 1955.

(Koblentz family archives).

Louise Mochon’s political deportee card.

(Koblentz family archives).

30 October 1956, Louise Mochon and Albert Koblentz on their wedding day, October 30, 1956.

(Koblentz family archives).

On January 30, 1956, Louise married Albert Koblentz[41], who she had met at a dance. They went on to have one daughter, Catherine Koblentz, who was born on July 24, 1959.

Albert Koblentz had also been arrested and deported, together with his brother, Isaac, a month before Louise, on Convoy 76.

Albert, Isaac and their younger brother Nathan had fled Paris after their parents were arrested. They went to Tarbes, in the Hautes-Pyrénées department of France, because Nathan knew someone who lived there. They arrived there on August 18, 1943 and registered with the departmental Refugee Service straight away. On August 21, the STO (compulsory work service) summoned Albert and Isaac and sent them to work for the Dumont company. On October 18, 1943, they were moved to the Ets. Morane-Saulnier aircraft factory, while Nathan worked for a photographer. On November 6, 1943, the Refugee Service clothing and footwear distribution department gave each of them a shirt and pair of trousers. All three brothers attempted to join the Resistance. Some time later, the Gestapo arrested Albert and Isaac, who were taken to Saint-Michel prison in Toulouse and then transferred to Drancy. Their younger brother, Nathan, who was tipped off by someone he knew, narrowly avoided being arrested and subsequently joined the Resistance. Albert and Isaac were deported and interned in the Auschwitz-Birkenau-Monowitz concentration camp[42]. When the camp was evacuated on January 18, 1945, Albert, who was too weak to be sent on the death marches, was left for dead[43]. The Russian army arrived just in time to save him from being sent to the gas chambers at the last minute. The Nazis decided to leave the camp immediately rather than stay on to kill the prisoners who could no longer walk. Isaac, although he too was very sick[44], was deemed fit enough to be sent on the death march to Gleiwitz, but died along the way[45].

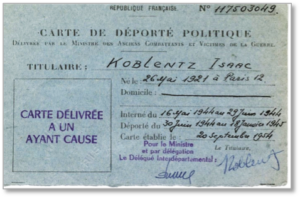

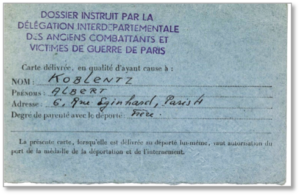

The political deportee card issued posthumously for Albert’s older brother, Isaac Koblentz, who died while on a death march in January 1945.

It states on the back that it was issued to Albert, as his next-of-kin.

(Koblentz family archives).

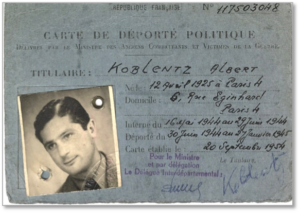

Albert Koblentz’s political deportee card.

(Koblentz family archives)

Nathan Koblentz, Albert and Isaac’s younger brother, in his Resistance uniform, in 1943 or 1944. He is wearing an armband bearing the Cross of Lorraine, which proves that he was a member of the FFI (Forces françaises de l’Intérieur, or French Interior Forces)

(Koblentz family archives).

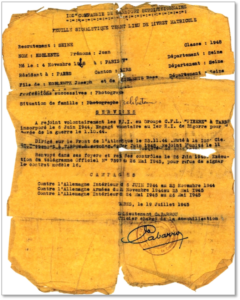

Nathan Koblentz’s personal information sheet, which doubled as his service record, dated 1945

(Koblentz family archives).

After the war, Albert initially worked in a matzo factory, and then became a second-hand goods dealer[46]. As for Louise, she worked in a warehouse for a while and then got a job as a sales assistant in a bakery. She also worked on market stalls, but only for a short time. She eventually found a steady job as a trouser presser in the Bril clothing factory on Rue du Renard in Paris[47], where she had her photo taken with two of her colleagues. She continued to worked there until she fell pregnant several years later, and was not well enough to return to work after the baby was born. Louise’s retirement pension record also shows that the time she spent in the camps was described as “military service during the war under the general system”, and as a result was counted as four quarters worth of pension contributions[48].

Albert Koblentz, Louise and Rachel began receiving a war veterans’ and civilian victims’ pension on July 31, 1957. Esteroula, who was not a French citizen, was not eligible. The family had a rough time in the post-war years, living in poverty and struggling with health issues[49]. The invalidity pension was thus (albeit very belatedly) a huge help. Much later on, they also received what is known in France as the “Jospin” compensation[50] and later still, another payment, which was released by the Claims conference.

Esteroula died it the Saint-Antoine hospital in the 11th district of Paris on January 29, 1969. She was 63 years old and had been in very poor health ever since she returned from the camps. She was still living at 77 rue Sedaine when she went into hospital. She was buried in the Pantin cemetery in Paris.

In June 1997, a clerk from the town hall in the 19th district of Paris, contacted Louise, following up on Serge Klarsfeld’s letter to the Arolsen archives. Louise’s daughter, Catherine, remembers that the clerk was very insistent, and that her mother refused to answer and asked Catherine to respond on her behalf.

On January 29, 2010, Rachel’s husband, Elias Sissa, died at the age of 82.

Albert Mochon, who remained single all his life and never had children[51], died in the Saint-Antoine hospital on November 3, 2013. Until he went into hospital, he was living in Saint-Mandé. He was buried, like his mother before him, in the Pantin cemetery in Paris.

On July 22, 2015, Louise’s husband, Albert Koblentz, died at the age of 90 in the Vaugirard hospital in Paris. We were able to find his address from his death certificate, which says that he lived in the 18th district of Paris and was married to Louise Mochon[52].

As we write this biography, in September 2024, Louise and Rachel, both widows, are still alive. Louise is 96 and Rachel is 99.

When she got back to France after being deported, Louise vowed never to talk about what had happened to her. She did not want her children to know what she went through in Auschwitz-Birkenau, hence her decision not to comply with Serge Klarsfeld’s request in 1996.

According to Catherine, Albert and Louise discussed the idea of giving testimony and passing on the memory of the deportation. She says that her mother told her that she remembered it all, but did not want to talk about the place which, as she put it, “got you by the throat” because it “was so distressing for the children”. Albert, on the other hand, did want to talk about it. These two contrasting attitudes, to remain silent or to talk about it, are not uncommon and provide an insight into both the extent of the trauma and the different ways in which people try to deal with it.

After we contacted Louise in May 2024, courtesy of their daughter Catherine, we were able to gather some valuable insights into the tragedy of the Nazi policy of systematic extermination of the Jews and how it affected the Mochon and Koblentz families.

Louise very kindly allowed us to make use of her family photos and the picture of the number that was tattooed on her arm when she arrived in Auschwitz-Birkenau on August 3, 1944.

We would like to extend our sincerest thanks to Louise and Catherine for their contribution to our research and this biography: we are enormously grateful to both of them.

Photo of the serial number tattooed on Louise Koblentz nee Monchon’s forearm, taken in May 2024.

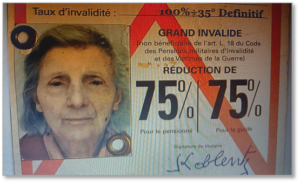

Louise Koblentz née Mochon’s disabled person’s card, which was issued due to her state of health after the deportation, and is still valid to this day.

(Koblentz family archives)

Drawings by Ondine Desaché.

Text written by Louis Vray, Pétronille Sécher-Léonelli, Eva Nahon, Shirine Aissaoui,

Louise Elissèche, Gabrielle Créquer, Maxime Caraty and Ondine Desaché, with the guidance of their teacher, Ms. Deroyer.

Notes & references

[1] The ITS, or International Tracing Service.

[2] In a report on the surviving deportee begun in March 1959.

[3] An exchange of letters between the Bad Arolsen archives services and the town hall of the 19th district of Paris.

[4] Living at 6 rue Eginhard in the 4th district of Paris.

[5] As a childless couple, they would have been immediately interned in Drancy: the Vel d’Hiv roundup (in French).

[6] Close examination of the plan of Drancy camp relating to Pessah suggests that he stayed in a number of different rooms.

[7] We know from Le Mémorial de la Déportation des Juifs de France de S. Klarsfeld, revised by J.-P. Stroweis, p. 57, that “On arrival at Auschwitz-Birkenau, the 370 men were assigned registration numbers 52883 to 53252 and the 630 women numbers 11345 to 11974”. We can surmise that Albert Koblentz’s parents were not murdered as soon as they arrived, but they did not survive.

[8] Koblentz family archives.

[9] Koblentz family archives.

[10] S. Klarsfeld, J.-P. Stroweis, ibid., p. 195: “A revised version of the Auschwitz-Birkenau calendar records that 91 women were selected to be assigned to the camp and that they were given registration numbers from 80569 to 80659. The remaining 865 people were gassed immediately.”

[11] Information on the back of their Drancy internment card, noted by the refugee reception service when they returned to Paris.

[12] Her mother and her sister as well.

[13] She is buried in the Pantin cemetery in Paris, Division 208, Row 5, Tomb 36.

[14] On this date, Pessah Mochon was declared to have died on September 19, 1942, in Auschwitz-Birkenau, rather than on September 14, 1942, in Drancy.

[15] He is buried in the Pantin cemetery in Paris, Division 135, Row 16, Tomb 23.

[16] He is buried in the Montmartre cemetery in Paris. His grave is referenced under number 7 DX 2015 and is located in division 20 / row 2 and grave 31, on the chemin Artot.

[17] This is often only given as “1903”, and the date of January 1st, which is found in some cases, appears to be a “substitute” date.

[18] Paris digital archives, 1926 census.

[19] It had previously been 10 years, according a law dating back to 1889.

[20]https://www.memoiredeshommes.sga.defense.gouv.fr/fr/arkotheque/client/mdh/recherche_transversale/bases_nominatives_detail_fiche.php?fonds_cle=19&ref=2573332&debut=0.

[21] In comparison with the file on Abraham Kaplan, who had been naturalized as a French citizen in 1906, and whose nationality is listed as “French by origin” on his Drancy record.

[22] In 1940, a law was passed that revised/revoked French citizenship by naturalization for anyone who had acquired it since 1927. Pessah’s Drancy card list his nationality as “Turkish”, while Esteroula’s card lists hers as “undetermined”.

[23]https://www.immigration.interieur.gouv.fr/Archives/Les-archives-du-site/Archives-Integration/Historique-du-droit-de-la-nationalite-francaise and Claire Zalc in L’Humanité Dimanche, n° 571, August 2017, pp. 77-81.

[24] As can be seen from the entries on their Drancy internment cards: Louise’s card says, “fr.or.” and Rachel’s says “française” (French).

[25] Many Jews from the East who lived in the Sedaine/Roquette neighborhood in the 11th district of Paris worked in the hosiery trade; they bought stock in bulk and sold it on markets in and around Paris.

[26] Rachel is listed in rue Keller school registers.

[27] We are not sure how much faith we can place in these statements, as Louise was working in the hospital at the time.

[28] “The vast majority (around 90%) of Jews in the Seine department registered themselves in October 1940. The Chief of Police informed the head of the military authorities in the Paris area on October 26: ‘This operation took place from October 3 to 19. By that date, 85,664 French subjects and 64,070 foreign subjects were registered, making a total of 149,734 Jews. Those who missed the deadline have up to July 1941 to register””: http://www.unlivredusouvenir.fr/recensement.html#:~:text=56%20690%20hommes%20et%2055,IVe%20(5%20%25).

[29] The documents provided by the French National archives in Pierrefitte archives refer to the liquidator of Esteroula’s business as A. Bonnier, Managing Commissioner, based at 96 rue de la Folie-Méricourt in the 11th district of Paris.

[30] The first convoy left on March 27, 1942.

[31] In fact, after passing her school certificate when she was 13, so in late 1942 or early 1943, Louise started work.

[32] https://seinesaintdenis.fr/actualite/culture-patrimoine/memoire/Yvette-Levy-enfant-de-Noisy-rescapee-des-camps/

[33] The Bad Arolsen archives refer to October, while Louise’s application to be recognized as a political deportee, p. 4, states that she arrived at Bergen-Belsen on November 30, 1944.

[34] Louise never knew exactly where Albert was sent to live in hiding, much to her regret.

[35] Ilsen About and Arnaud Nemet, “L’histoire de Lisette Cohen Abouth” (The story of Lisette Cohen Abouth), in Suppl. Kaminando I Avlando, no. 42, May 2022, p. 50. Magazine of the Aki Estamos organization – Les Amis de la Lettre Sépharade (Friends of Sephardic Literature) founded in 1998 April, May, June 2022 Nissan, Iyar, Sivan 5782.

[36] Source: Bad Arolsen archives, List of French nat. repatriated from Belsen camp to France. The list was made in French and says “par cam”, meaning “by truck”. We noticed some errors in the early records, which were drawn up during the chaotic aftermath of the liberation of the camps. One record from Bad Arolsen even states that they died. In their Drancy records, the information provided when they returned to France clearly states that Esteroula, Rachel and Louise were repatriated by train.

[37] There were three categories : “Good”, “Average”, and “Poor”.

[38] https://www.legifrance.gouv.fr/codes/section_lc/LEGITEXT000006074068/LEGISCTA000006174250/

[39] Rachel Mochon and Elias Sissa’s marriage certificate from the Paris digital archives. Elias is referred to as an “optician”, which Louise’s daughter finds surprising because Elias was in fact working at the Canonne pharmacy at the time.

[40] Jacques Sissa, born on December 19, 1946 in the 12th district of Paris and died on August 19, 2007 in the 11th district of Paris, never having had children. Michel Sissa, who was born in November 1954), had one son, Rudy, who was born in July 1981 and who has two daughters, Nina and Rachel.

[41] The son of Joseph Koblentz (a Russian citizen born in Kreuzburg/Krustpils in Latvia) and Szosza Rywka Zakheim (a Polish citizen born in Warsaw) , both of whom were deported on the convoy of July 24, 1942.

[42] “This convoy transported 1,156 deportees, including 654 men. 256 of them were gassed as soon as they arrived at the Birkenau extermination camp on July 4, 1944. 398 entered the camp. They were sent to the Monowitz camp, one of the three camps in the Auschwitz complex, also called Auschwitz III.” from Transferts et évacuations du complexe d’Auschwitz (Transfers and evacuations from the Auschwitz complex): https://www.cercleshoah.org/IMG/pdf/marches-mort-evacuation-monowitz.pdf (based on testimonies of deportees from Convoy 76 and archive material)

[43] “Furthermore, 63 prisoners from convoy 76, weakened by months spent in deportation camps, were not in a fit state to leave on January 18. All those who were ‘unfit’ to undertake the march, whether injured or sick, were left behind in the Monowitz camp by the Nazis.” ibid.

[44] “Deported prisoners also mention fellow prisoners who were sick but who nevertheless set out on the road, such as Franz Kettner (”He had severe phlegmon in his leg”) Karl Stark, (“He had a broken left arm and was in very poor health”), Samuel Meniack, Isaac Koblentz, André Carnos. Having never seen them again, they assume that they were shot during this first march, as were many others, no doubt”. Testimonies of deportees from Convoy 76 and archive material. ibid., pp. 7-8.

[45] “The SS units forced nearly 60,000 prisoners to march westward from the Auschwitz camps. Thousands of prisoners were killed in the camps a few days before the start of the death march. Tens of thousands of prisoners, most of them Jews, were forced to march 55 kilometers northwest to Gliwice (Gleiwitz (…) At least 3,000 prisoners died on the road to Gliwice (Gleiwitz), and about 15,000 others lost their lives during the evacuation marches from Auschwitz and the subcamps.” Note: 55km is around 34 miles. From: https://www.cercleshoah.org/spip.php?article264#:~:text=Les%20prisonniers%20souffrirent%20du%20froid,Auschwitz%20et%20des%20camps%20secondaires.%20%C2%BB

[46] Before the war, he had done some basic training in the electricity trade, while his younger brother planned to become a photograph retoucher.

[47] Catherine clearly remembers the employer’s name, as it was often listed in movie credits. Louise was obviously very proud of this, and Albert and Catherine would tease her about it.

[48] This entitlement applied to everyone who was granted “political deportee” status. https://holocaust-compensation-france.memorialdelashoah.org/en/index_engl.html

[49] Like all deported persons, she was issued (many years later) with a care booklet listing the illnesses attributable to deportation and for which she is entitled to a pension. She had to stop working for good during her pregnancy due to health reasons, as can be seen from her pension record.

[50] The Jospin decree of July 13, 2000, allows any person, French or foreign, who was under the age of 21 at the time of the events, whose parents died as a result of deportation, in a camp or by firing squad, to obtain compensation. “It is part of a comprehensive approach aimed at helping the direct or indirect victims of the Holocaust to obtain compensation for the violence and losses suffered during the Second World War”.

https://holocaust-compensation-france.memorialdelashoah.org/en/index_engl.html

[51] Albert Mochon did his national service at the military academy, working as a driver. Then, after a spell working as a market trader, he became a yoga instructor.

[52] Misspelled “Mochan” rather than “Mochon”

Français

Français Polski

Polski