Charlotte ALTER

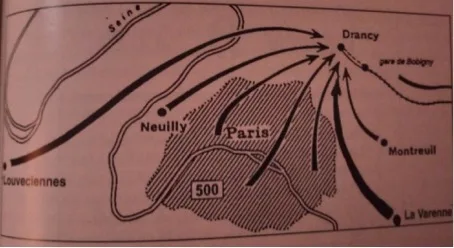

We are a group of 9th grade students from the Les Blés d’Or secondary school in Bailly-Romainvilliers in the Seine-et-Marne department of France. We took on the task of writing the biographies of Berthe and Charlotte Alter as part of our work with the Convoy 77 non-profit organization, an educational project designed to teach 21st century teenagers about the Holocaust in an alternative way. The project was founded by Georges Mayer and has been rolled out in the thirty-two countries from which the deportees came. Convoy n°77, or simply “Convoy 77” was the last of the large deportation convoys of Jews to leave Drancy internment camp, via Bobigny railroad station, bound for the Nazi extermination camp at Auschwitz-Birkenau, in eastern Poland. It set off on July 31, 1944. Aboard the convoy were 1,306 people who travelled in cattle cars, 836 of whom were sent to the gas chambers as soon as they arrived in Auschwitz. Only 250 of them survived. Berthe and Charlotte Alter, who were 6 and 4 years old at the time, were among the Convoy 77 deportees who were executed in Auschwitz Birkenau. We split into two groups to research what happened to the two girls, but then decided to write a joint biography because their stories were so similar.

We found a Genially on the Internet, produced by Stéphane Amélineau, a teacher from Joinville, based on the book Les Orphelins de La Varenne (The Orphans of La Varenne), of which we obtained a copy. It features numerous sources and testimonials, including life in the orphanage, the children’s arrest, their arrival at Drancy, the travelling conditions and their arrival on the ramp at Birkenau. It was from this that we drew our inspiration.

Berthe Alter was born on September 20, 1938 in the 10th district of Paris. She had three sisters, Lise, who was born on March 31, 1933, Rosine, born on September 30, 1934, and Charlotte, born in Paris on May 2, 1940, and one brother, Nathan, who was born on September 9, 1936. Their father’s name was Salomon Alter. He was born in Bucharest, Romania, on August 10, 1893. Their paternal grandparents were Leibu Alter and Lisa Gold. Their mother’s name was Ruchla Ita Modrzeniecka and she was born in 1902 in Szydlowice, Poland. Their maternal grandparents were Manachem Modrzeniecka and Fajça Zalctregier. The family, which was Jewish, had Romanian and Polish roots.

Berthe and Charlotte lived at 17 rue Ferdinand Duval in the 4th district of Paris, from the time of their birth until the beginning of the war in September 1939. In 1943, the whole family was rounded up. From the Shoah Memorial website, we discovered that Berthe and Charlotte were interned in Drancy from March 19 to 22, 1943. They were then transferred to an orphanage, while the rest of the family was deported on convoys 52 and 53 in March 1943. The orphanage, La Varenne Sainte Hilaire, was in Saint-Maur-des-Fossés in the Val de Marne department of France. Before the Second World War, it had links with the Bastille neighborhood of Paris, which was home to a large Jewish community. This facilitated the development of Jewish orphanages in what was at that time quite a rural setting, on the banks of the river Marne. It was run by the UGIF, an organization that took care orphaned Jewish children, and was previously called as “Beiss Yessoïmim”. UGIF stands for Union Générale des Israélites de France, or General Union of French Jews. It was founded by the Vichy regime on November 29, 1941, at the request of the Germans. The UGIF was responsible for helping Jews with their dealings with the French authorities and for taking care of children left behind after their parents had been arrested. This was the reason that the UGIF children’s homes, most of which had previously been Jewish residential homes, were founded.

The La Varenne orphanage housed around twenty children, who the staff tried to keep out of the clutches of the Germans. Berthe and Charlotte, who had been arrested at the same time as their parents, were what were known as “blocked children”. This meant that they were on a list of children compiled by the Germans and effectively under house arrest, which made it more difficult to protect them. However, despite the trauma of the roundups and the separation from their families, the teachers did their best to make life as normal and enjoyable as possible for the children: on the face of it, nothing seemed to interfere with the smooth running of the orphanages. School activities, singing, storytelling and poetry readings by the social workers, gifts to mark the Jewish festival of Hanukkah (the Festival of Lights), Hebrew language lessons in song, medical check-ups: these were all part of the daily routine for the two sisters. The children played games, which kept them amused and stopped them getting bored. During school time, they went to local schools. From 1942 onwards, children aged 6 and over had to wear the yellow star whenever they left the orphanage. They had plenty to eat, despite food shortages and rationing, and the orphanage had its own vegetable garden. Potatoes, vegetables and milk could be bought from nearby farms in Chennevières.

Berthe and Charlotte may well be in the following photo, but unfortunately we have no way of knowing, because not all of the children have been identified.

Sadly, on the night of July 21-22, 1944, on the orders of SS commandant Aloïs Brunner, the SS and Gestapo rounded up all the children from the UGIF orphanages in around Paris. Only one child survived this tragedy and later testified as to what happened that night. His name is Albert Szerman. He was born in Paris in 1936, so was only 8 years old at the time. He gave his account in 2004 in a book written by the Groupe Saint-Maurien contre l’Oubli, entitled Les Orphelins de la Varenne (The Orhpans of La Varenne). He describes how the children were woken up in the middle of the night, and how they had no idea what was going on: “The roundup struck the Orphanage on the same night as the nearby Zysman boarding house was hit. The Orphanage was surrounded and the SS ordered it to be evacuated, but the children, overcome by panic, refused to come downstairs. To show that they were serious, the SS shot at the front of the building with machine guns (the bullet holes remained visible until the building was demolished in 1982).

Eighteen terrified children emerged from the orphanage. They were loaded onto a bus, along with five female staff members. However, one of them convinced the Germans that she was not Jewish and she was allowed to leave.”

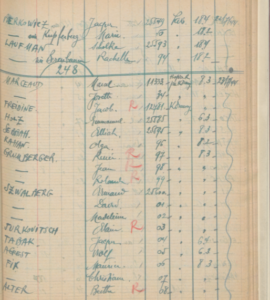

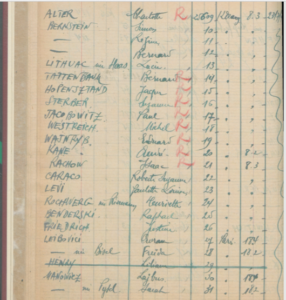

On July 23, the children arrived at Drancy camp. Their names, including those of Berthe and Charlotte, were listed in a register (see below. The red R after their first names stands for “réintégré” (reintegrated, or re-entry), which confirms that this was the second time the girls had been admitted to the Drancy camp (the first time having been with their parents, in 1943). 28 enfants et 7 care givers from the orphanage were registered. Berthe was assigned the number 25608 and Charlotte 25609. They and the other children were sent to a room on the “4th floor, staircase 8”. The living conditions in the camp were appalling, especially for two children aged 6 and 4, despite the dedication of the UGIF carers, who did their utmost to make them forget their fears and the prison environment.

The Drancy camp arrivals register (Shoah Memorial/French National Archives, ref. F9/5788).

In his book L’Impossible Oubli (The Impossible to Forget)(1), internee André Warlin recounts the children’s arrival and stay in Drancy camp, and the conditions in which they were held:

“One clear, starry night, we could make out the distant sound of buses arriving in rapid succession, their whistles announcing their arrival. They came one after another. We didn’t see the new arrivals right away. But soon, to our indescribable horror, we heard the bubbly, chattering voices of little children, all alone, without their mothers or fathers. Some were as young as two, as they dragged along their pitiful little bundles. They were crying. They hadn’t even had time to get dressed, they’d been dragged out of bed and shoved around.

Here and there, a woman walked beside them, dragging them along behind or pushing them in front of her.

They were herded into empty staircases, with improvised diapers, and crammed together into bedbug-infested beds. The whole camp was in uproar […]

The following day, disciplined, well-behaved, used to obedience and suffering, they all lined up in the dining hall, holding oversized bowls in their little hands and playing with their spoons. The five-year-olds took care of the three-year-olds. As for the rest, they were more mature and adaptable. They already knew what this life was like, the persecution, the suffering. They had been separated from their parents, many of whom had already been deported, most of them following the Vel’d’Hiv round-up. They knew they were Jews, in fact that was the only thing they knew, and they often didn’t even know their own names. They knew they were in danger, having heard about the deportation camps from birth. As little children, they had an instinct for self-preservation, like baby animals. They tried to flee from danger. One of them was found in a dog kennel. “I want to be a dog,” he said, “because dogs don’t get deported.””

On July 31, Berthe and Charlotte were taken by bus to the nearby train station and deported in cattle cars to Auschwitz-Birkenau. This was the largest concentration and extermination camp in the Third Reich. It was in the province of Silesia, in Poland.

The journey lasted three days and the travelling conditions were unbearable: they must have been exhausted when they arrived on the ramp at the Birkenau camp in the early hours of the morning, only to be selected to die immediately.

Denise Holstein was 18 when she was arrested at the Louveciennes children’s home and subsequently deported. When she returned to France in 1945, she wrote about her experience. This is how she described the children’s journey to Auschwitz:

“From Drancy camp, July 31, 1944] the bus took us to a little station near the camp. There, the cattle cars were waiting for us, and inside they had already loaded up some supplies, buckets and even mattresses, and we had to cram 60 more people into the remaining empty space. As best we could, we made space for the 48 poor youngsters on one side of the car, while on the other, the 12 older people squeezed between the bundles beside the supplies.

At midday, the convoy set off. 1,300 of us were being carried off into the unknown. The first day wasn’t too bad, but in the evening, when we had to put all the children to bed in the dark, the screaming started, and we couldn’t sleep a wink: the children were hot, thirsty and the air was running out, the openings were so small. That same evening, we crossed the Rhine and left the country. In spite of all that, our spirits were high – they had to be, we had the children and we had nothing to whine about. We sang travelling songs and songs of hope. The journey lasted two and a half days, and that was just the beginning of the suffering. It was great to have food, but we couldn’t swallow a thing – we were all so thirsty. The children cried, and we had to console them and make them be patient until our tormentors let us out to fill our water containers. As I had a red armband, I was able to get off at a few stops with the doctor, and at the same time breathe in some fresh air, drink my fill and wash myself a little. The train was starting to get a bit quieter, and the children were falling asleep when it came to a halt.

We could hear shouting in German, the doors were opened and the journey was over [the was during the night of August 2/3, 1944]. Men dressed in convict uniforms, their heads shaved, took the children in their arms to get them off the train; the poor little mites were mostly barefoot and naked; they were frightened by these unfamiliar-looking men, the vast majority of whom were foreigners. Among these men was a young man with big blue eyes, impeccably dressed, despite his striped uniform; I immediately asked him how he could be anything other than French! He replied through his teeth, so that the others wouldn’t see him speak: “Get back on the train. I can’t talk to you here”. I obeyed and he came over and told me straight away what the camp was like: food, just enough to keep you from starving, no place to lie down at night, rollcalls all the time and, he said, above all, when you get off the train, whatever you do, don’t pick up any children”. I asked him why, and he replied: “You’ll understand in a few days”. I really had no idea what he meant. “See them,” he said, pointing to the kids, “they’re going to be turned into soap”. He’d just told me he’d been in the camp for two years, so I thought he was crazy. I asked him if he knew of any Holsteins in the camp, and with a smile he replied: “There are maybe several million of us in this camp, and I’d advise you to stop asking about your family and, above all, to stop thinking about them”.

I was quite anxious when I got off the train, but didn’t want to say anything to my friends. There would be plenty of time to figure it out later. As I got off the train, I saw a little girl all alone, crying, and I couldn’t bear to leave her like that, so I took her by the hand and walked on for a while, until I recognized the man next to me, the Frenchman I’d just been talking to. He repeated in a firm voice, “You haven’t grasped what I told you about the children!” With a heavy heart, I left the little girl, who was no longer on her own, but in the midst of the crowd, and stepped aside to join two young women who were walking together, without children.

It was pitch dark, with floodlights lighting up the road. The train had stopped inside the camp; there was no real station. We were walking alongside the train when, across the road, a group of Germans were giving orders, sending some people to the right, where there were some trucks waiting, and others, including me, to the left. Right away we noticed that all the children were heading for the trucks, as were the older women, and all the people carrying children in their arms.”

Denise Holstein, together with 282 other women and 291 men, was selected for internment in the camp. All the others, including the children, were sent to the gas chambers and killed immediately.

On November 21, 1947, Ruchla Modrzenicka, the girls’ mother, requested a certificate confirming that her daughters had not returned from the camps. She then applied to have them recognized as having been political deportees, meaning that they were deported for political reasons. Her husband supported her through the formalities, as none of the children survived. How did they themselves manage to escape and return to France? We have no information about this.

The commemorative plaque at the former orphanage in Saint-Maur-les-Fosses, which was unveiled in 1986.

A sculpture in the Square Saint Hilaire in Saint-Maur-des-Fosses, inaugurated in 2000. Entitled “Hommage” (homage or tribute) it was designed by Pierre Lagénie in memory of the deported children and the local people who tried to save them. On one side, there are two children set in a wall, which might represent a railway car or a gas chamber: they are encircled by barbed wire to suggest that it was impossible to escape. On the other side, a child kept in hiding is approaching two adults, rescuers, a man and a woman, who are intended to symbolize life.

Sources :

- Jean Laloum, « L’U.G.I.F. et ses maisons d’enfants : le centre de Montreuil-sous-Bois », le Monde juif,1984 p 153 à 167

- https://view.genial.ly/5e5a7a6c3ca5910fdcf62e45/presentation-les-orphelins-de-la-varenne-juillet-aout-1944

- André Warlin, L’impossible oubli. Éditions La pensée universelle, Paris, 1981.

- collectif : Les orphelins de la Varenne, 1995.

- Serge Klarsfeld, Le calendrier de la persécution des Juifs de France 1940-1944. Editions FFDJF, 1993.

- Groupe Saint-Mauriens contre l’Oubli, Les Orphelins de la Varenne, édition L’Harmattan, 2004

Français

Français Polski

Polski