Elie BENSO, l’amoureux

I. Elie’s parents, Moïse and Esther, who moved to France in search of a better life

Elie Benso was born on November 16, 1925 in Paris, France. His parents were Turkish: both were born in Constantinople.

His father, Moïse Benso, who was born in 1901, was a day laborer, which meant he was paid by the day. This was a very insecure job.

HIs mère, Esther Tchiprot, who was born in 1899, was a “housewife”[1].

His parents emigrated from Turkey soon after the Turkish Republic was founded in 1923[2]. The first arrived in Marseille, on the south coast of France[3], then moved to the same apartment building as some other family members: according to the 1926 census, the Tchiprot and Benso families both lived at 22 rue de Belfort, in the 11th district of Paris[4].

The Benso family was made up of the grandmother, Estréa, a widow born in 1877 and Moïse; Esther; and Israël, who was born in Paris in 1925—this must surely be Elie[5].

The Tchiprot family included Vida, a widow born in 1877[6], her son David, born in 1904[7]) and another child, born in 1909[8].

II. Elie’s childhood

Elie’s birth certificate states that he was born on November 16, 1925, at 19 bis rue Chaligny in the 12th district of Paris, which was the Saint-Antoine Hospital. He lived for a few years at 22 rue de Belfort, in the 11th district. The family then moved to 36 bis rue des Amandiers in the 20th district.

The family was already living there in 1931, according to that year’s census. Moïse’s 1933 voter registration card confirms this. Only the four of them were still living there, however: him, his parents, and his sister Sole.

36 rue des Amandiers is no longer there now, but behind the site where it once stood is number 38[9], a group of buildings surrounding a large courtyard. Elie must have lived in a traditional Parisian building with narrow staircases leading down to this courtyard.

In 1932, Elie, his sister and his father were naturalized as French citizens[10].

III. Violette, the love of his life

We visited the 20th district with guidance from the Shoah Memorial staff. We learned that a large number of Jewish families lived in this area and, as the apartments were cramped, the children often went out to play.

It was there that Elie met Violette Parsimento. She was born on November 13 1925: there were only three days between them!

Violette lived at 14 rue des Amandiers, just a hundred yards or so from 36 bis rue des Amandiers. Their birthdays being so close together meant they had something in common. They soon became inseparable. They both came from low-income families and had to start work at an early age: Violette worked in the goatskin tanning industry, while Elie was a mechanic.

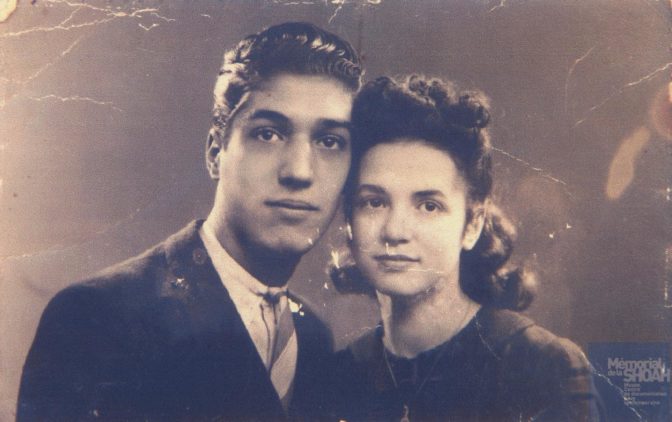

We can only imagine how difficult everyday life must have been for them during the war and with the persecution of the Jews[11]. They got engaged nonetheless and went to a photographer to have their picture taken. They planned to throw a party and celebrate properly once the war was over.

Elie and Violette’s engagement photo © Shoah Memorial, Paris

Serge Klarsfeld submitted this photograph of the two of them to the Shoah Memorial. Elie and Violette are named, but there are no other details.

On October 5, 1943, Violette’s father was arrested, followed a few months later, on March 7, 1944, by her mother and sisters. Violette herself was not at home at the time. She could hardly alone in the 20th district after that, so sought refuge with the UGIF (Union Générale des Israélites de France, or General Union of French Jews), a Jewish-run organization founded to help Jewish families. which offered her a place in one of their children’s homes, at 9 rue Vauquelin in the 5th district of Paris[12].

She was arrested during the night of July 21-22, 1944, as part of a round-up of all the UGIF homes in and around Paris. All of the young women who were staying in Rue Vauquelin that night were arrested[13].

Elie, who was madly in love, was devastated when Violette was arrested.

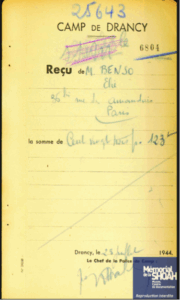

Yvette Levy, who was with Violette in the home on Rue Vauquelin and in Drancy camp, later recounted that Elie insisted that he be arrested too, so they could be together. He reportedly went to Drancy three times before a guard finally agreed to let him into the camp. He was interned on July 23, 1944. As he entered the camp, he was searched and handed over 123 francs[14].

Elie’s search receipt from Drancy camp © Shoah Memorial, Paris

As for his parents, all they knew was that he left home that day and never came back.

IV. Internment in Drancy

The Germans took over Drancy camp in June 1940, and used it as a short-term internment camp for prisoners of war and foreign civilians. As of 1941, it became a transit camp for Jews[15].

Living conditions in the camp were very tough. There were a few bunk beds, but only about 20 water taps for the 5,000 or so people interned there. When they arrived, the Jews had their identity papers, money and valuables confiscated[16].

V. Deportation

On July 31, 1944, after spending a week in Drancy, Elie was loaded onto a train and deported to Auschwitz. The Germans told the Jews that they were going somewhere to work, but there were over 300 children on the train, and everyone wondered what was going to happen to them. For the time being, some young women were taking care of them.

Elie was in the same car as Violette Parsimento and Yvette Levy[17], who later recounted how he sang songs to Violette along the way.

The deportees were crammed into cattle cars, with so little room that they had to stand up most of the time. The journey took three days and they had only one bucket to relieve themselves, which soon overflowed[18].

When they arrived in Auschwitz, most of the prisoners were loaded onto trucks that took them to the gas chambers, where they were executed.

Only those who were deemed fit enough to work were selected to go to the concentration camp, where they were forced to work until they were exhausted.

Elie was not selected for work: he died in the gas chambers on August 3, 1944[19].

Violette, however, was selected for work, so was sent into the camp, where the notorious Dr. Mengele carried out medical experiments on her. He reportedly chose her because she was pregnant. Mathilde Jaffé, who survived her time in the camps, later testified that Violette died as a result of the experiments in early February 1945, by which time she had been transferred to the Bergen-Belsen camp (see Violette’s biography). If what Mathilde Jaffé said about Violette is true, Elie gave his life not only for his girlfriend, but the mother of his unborn child.

VI. After Elie’s death

The archives contain various records of Elie’s parents’ efforts to trace him after the war. Starting in September 1945, they wrote to the Polish Red Cross in an attempt to locate him. Years later, by which time they were living in Israel, they resumed their efforts. In 1962, they applied to have him officially recognized as a “political deportee.” They stated that on July 23, 1944, Elie “left home at 36 bis rue des Amandiers, in the 20th district of Paris, and never returned,” which seems to support the claim that he went to Drancy of his own accord. This was the same date on which he handed over the 123 francs to the Drancy authorities.

Elie’s father said he thought Elie had been arrested in the street because he was Jewish. He said that he was in hospital on July 23, having recently been repatriated from a prisoner of war camp in Silesia. Élie’s mother, meanwhile, said that she and Sole, his sister, had received a letter from Élie saying that he was in Drancy and not to worry about him.

We found a few records relating to his sister, Sole. She had worked as a laboratory technician and was divorced from Samuel Gattegno. She died in Poissy, in the Yvelines department of France, on January 24, 2011.

We also found records of an Elie Gattegno, who was born in Israel in 1949. His parents were Samuel and Khokhavet Gattegno. Might this be another name for Sole? Did she name a son after her late brother[20]?

Notes & references

[1] A woman who did not work outside the home.

[2] The establishment of the Turkish Republic in 1923 caused great anxiety among Jewish communities. The Jews who had settled in the Ottoman Empire centuries earlier spoke mainly Judeo-Spanish. Some had learned French thanks to a school network, which was founded by a French Jewish institution, the Alliance Israélite. However, a policy of forced “Turkification” forced minority groups to use the Turkish language as of 1934.

[3] There is a trace of Moïse and Esther in Marseille, in an announcement in the Petit Provençal newspaper dated February 11, 1924: the couple married in that city that month. He was living at 29 cours Belsunce, and she on rue Glandeves. Marseille was the port through which most Turks and Greeks arriving in France entered the country. From Marseille, many of them moved to Paris, where they often had family.

[4] In the 11th district, there was a neighborhood known as “Little Turkey” because of the large number of Turkish immigrants who lived there. Almost all of the people who lived in their crowded apartment building were Jewish families originally from Turkey.

[5] Although his birth certificate only lists one first name, Elie, which is a Jewish name. On this birth certificate, Moïse is listed as a “laborer”.

[6] She died in March 1953.

[7] He was deported and died in August 1942.

[8] The Pisanti family also lived in the same building. The father, Albert, and the daughters, who by then had moved to the 14th district of Paris, were also deported on Convoy 77.

[9] The neighborhood has since been completely redeveloped.

[10] When war was declared, Moïse, who was a French citizen, was called up. He fought at the front and was taken prisoner. Elie then became the breadwinner, and supported his mother and sister.

[11] A ominous mood hung over the Jewish community in general and Elie’s family in particular. The two decrees on the status of the Jews had banned them from all kinds of things: working in most professions, owning a telephone, a car, a bicycle or a radio and going to the movies, the theater, or public parks. They were obliged to ride in the last subway car, had to register themselves as Jews and had to wear the Jewish star, although Turkish Jews were exempt from this until 1943 (although this did not apply to the Benso family, who were French citizens).

[12] This Jewish organization, under the supervision of the Commissariat Général aux Questions Juives (General Commissariat for Jewish Affairs), was responsible for helping families and placing orphaned children and children whose parents had been deported in “homes.” Violette was placed in the home on Rue Vauquelin. She was allowed to go out to work during the day, but spent the night in the home with around twenty other girls who, like her, had no family. But a safe refuge it was not!

[13] The staff members were also arrested. The roundup was organized by Aloïs Brunner, the Nazi commandant of Drancy camp, who wanted to deport all the children from the UGIF homes in and around Paris. Almost all of them were deported on the same convoy as Elie et Violette, the others a little later.

[14] What Elie did not know is that women and men were kept in separate buildings and were only able to meet briefly in the courtyard, when they were allowed down there.

[15] Drancy camp, which was initially an internment camp but later became a transit camp, was based in a building complex called the Cité de la Muette, was originally intended to provide low-cost housing for families. It was the main transit camp for Jews who were deported from France, almost all of them to Auschwitz.

[16] Aloïs Brunner took over as camp commander in 1943, after having deported nearly 50,000 Jews from Austria, almost as many from Thessaloniki, and, during his time in Drancy, also went to Nice to conduct roundups there. Communication with the outside world was forbidden by this time, as were parcels, but news still managed to get through, as did a few parcels. Elie thus managed to send his mother one last letter to reassure her (see below). His parents, of course, were unaware that their son had thrown himself into the lion’s den. They thought he had been arrested in the street or during a roundup, which could happen to any Jew.

[17] As well as the young girls from rue Vauquelin.

[18] The train arrived during the night of August 3-4. Many of the deportees, especially those who were sick or elderly, did not even survive the journey.

[19] This is odd, given that he was only 18 years old and in good shape. Might he have objected when the men and women were separated on the platform?

[20] Or is this more likely to be Sole’s husband? This Elie Gattegno died in Paris on May 6, 2021.

Français

Français Polski

Polski