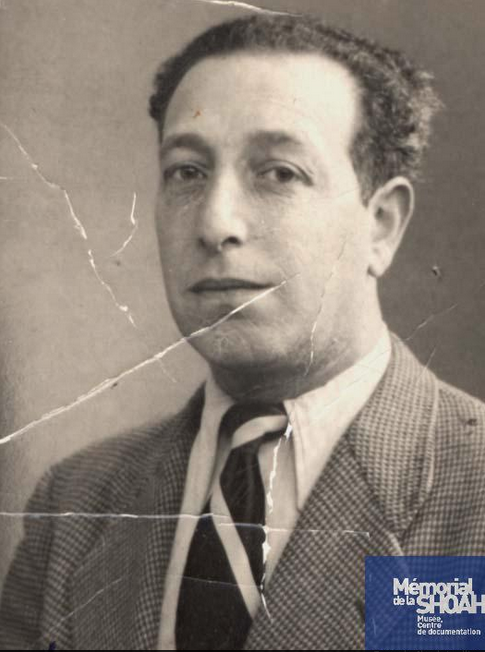

Jacques DRUCKER

Jacques Drucker was born on November 26, 1901 at 43 rue Simart in the 18th district of Paris[1]. His parents were Chaïm Drucker, a tailor, and Beïla Roman, both of whom were originally from Austria. When they were married, on December 3, 1904, the parents officially acknowledged that Jacques, his sisters, Jeannette, who was born in Berlin in 1896, and Juliette, who was born in Paris in 1904, were their children. The family was living at 27 rue Simart at the time[2]. Jacques was granted French nationality by means of a declaration made before the Justice of the Peace of the 17th district of Paris on June 11, 1915[3]. As a result, he had to carry out his French military service, and was drafted into the army in April 1921. He was promoted to corporal on October 7, 1921, and then, on December 21, 1922, after training at the Andelys military academy, to the rank of sergeant. He was discharged on May 30, 1923 with a good conduct certificate. He was transferred to the reserves in 1925, but was discharged with a residual fracture of his right leg at the start of the Second World War. According to his military service record, he had previously been a interpreter and worked as a salesman[4].

On October 27, 1932, Jacques married Dobrisch Rose Goldfeld, who was born in Chargorod in Russia on December 6, 1906. Her parents were Beila and Haïm Goldfeld. The couple moved in with the Goldfelds, who lived at 47 rue Boinod in the 18th district of Paris[5]. It was there that their two children were born, Raymond on June 23, 1933, and Maurice Raoul on January 21, 1936. Dobrisch was working as a shorthand typist at the time[6].

The family then moved to 37 rue Boinod and were still living there on July 23, 1944 when Dobrisch and Jacques were arrested[7]. The Paris Police Headquarters register lists the reason for their arrest as “Jewish” and the authority responsible for it as “Jewish affairs”[8]. Dobrisch Drucker later applied for her husband to be granted the status of déporté politique, or political deportee (meaning that he had been deported for political reasons), stating that the Gestapo had arrested him near their home. The Police Justice Department’s internal investigation confirmed this on August 10, 1953[9]. Dobrisch also stated in her application that Jacques had worked at the Renault factory but had also been a salesman and interpreter[10]. Jacques and Dobrisch were interned in Drancy camp on July 24 and deported to Auschwitz on Convoy 77 on July 31, 1944[11].

In a statement relayed by the Police Justice Department, Dobrisch explained that she had been transferred to a different camp to the one where her husband was sent, and that she had not heard from him since[12]. In fact, Jacques was sent to the Struthof camp, where he was assigned to metalworking tasks as of October 28, 1944[13]. Dobrisch, meanwhile, was transferred to the women’s camp in Kratzau (now in the Czech Republic)[14]. Despite the fact that the Allies were advancing rapidly across France, and that most of the prisoners in Struthof were already being evacuated to Dachau, the German authorities must have wanted to exploit the experience that Jacques had gained at Renault to the full, so transferred him to Struthof nevertheless. From 1943 onwards, Struthof was focused mainly on the war effort, in particular the production of aircraft engines[15]. Jacques must have been one of the camp’s last remaining prisoners, as he appears to have been executed just before the Americans arrived there on November 25 1944[16].

Aside from the Paris Police Headquarters arrest register (Drucker-Dobrisch-APP_CC2-9) and an information sheet from Struthof held in the Bad Arolsen archives (Enveloppe-STUTTHOF-1.1.41. 2-4454061-62), the students worked mainly on a large dossier from the Victims of Contemporary Conflicts Archives Division of the French Defense Historical Service in Caen, Normandy. This included all the documentation that Dobrisch Drucker gathered and produced as she dealt with various official procedures after she returned to France. The references of the 58 records within it were “Drucker-Jacques-DAVCC-21-P-445-173-1” to “Drucker-Jacques-DAVCC-21-P-445-173-58”. To make the biography easier to follow, we have abbreviated these to “DAVCC1” to “DAVCC58”. Starting in August 1945, Dobrisch embarked on a series of official requests. The first was to ask for news of her husband[17] and then to prove that he was a “non-returned person” so that she could claim a war pension[18]. In 1947, she applied for him to be granted the status of “Died for France”[19] which was awarded later that year. This entitled her to a war widow’s pension and made the children wards of the State[20]. Lastly, in 1951, she applied for him to be granted the status of “political deportee, which was agreed in 1954[21] and entitled her to 12,000 francs in compensation[22]. The main limitation of this collection is the very short period it covers: primarily the arrest and deportation. In some cases, the records reveal contradictions between the details that Dobrisch provided and those compiled by the French authorities. There are also some gaps in the documentation. Nevertheless, this research enabled us to identify Jacques’ specific deportation route, from Auschwitz to Struthof, and to highlight the complexity of the administrative challenges that victims faced as they sought to have their status acknowledged and to assert their legal rights. To complete Jacques Drucker’s biography, the students also managed to find three invaluable records in the digital archives from Paris City Hall : Jacques’ birth certificate[23] his parents’ marriage certificate[24] and his army number[25]. These records made it possible to document Jacques’ life before he was married, and in particular his Austrian roots.

Sources and references

[1] Paris Civil Registry, Civil status register from 1860 onwards: 1901, Birth, 18, V4E10466 (act number: 5571).

[2] Paris Civil Registry, Civil status register from 1860 onwards: 1904, Marriage, 18, 18M330 (act number: 2532).

[3] Certificate of nationality (DAVCC16).

[4] Seine department military recruitment records, Recruitment number registers (1887-1921) Drucker, Jacques, army number 2834, D4R12292.

[5] Marriage bulletins (DAVCC48 et 49)

[6] Raymond and Maurice Raoul’s birth certificates (DAVCC36) and (DAVCC37).

[7] Seine department military recruitment records, Recruitment number registers (1887-1921) Drucker, Jacques, army number 2834, D4R12292.

[8] Paris Police headquarters register (DRUCKER-Jacques-APP_CC2-9).

[9] Application for the status of political deportee – page 3 (DAVCC25) and report from the Police Justice Department (DAVCC31-32).

[10] Application for the status of political deportee – pages 1 and 3 (DAVCC23 and DAVCC25).

[11] Paris Police headquarters register (DRUCKER-Jacques-APP_CC2-9), attestation letters (DAVCC13 and 14), official information request (DAVCC33).

[12] Police Justice department report (DAVCC31 and 32).

[13] Stutthof dossier (Enveloppe-STUTTHOF-1.1.41.2-4454062-recto_1.1.41.2).

[14] See the biography of Dobrisch Drucker.

[15] https://www.struthof.fr/le-site/le-kl-natzweiler

[16] Death certificate (DAVCC3), official information request (DAVCC33), Sworn statement (DAVCC42).

[17] Lettrers from Dobrisch (DAVCC53 and 55).

[18] “Non-returned person to date” certificate (DAVCC34), request to update civil status record (DAVCC43-46).

[19] Request for “Died for France” status (DAVCC8) and the Prefect’s approval (DAVCC9).

[20] Raymond and Maurice Drucker’s birth certificates (DAVCC36 and 37).

[21] Request for “political deportee” status (DAVCC23-28) and granting of “political deportee” status (DAVCC30).

[22] Checklist for the payment of compensation to the beneficiaries of deceased political deportees (DAVCC21).

[23] Paris Civil Registry, Civil status register from 1860 onwards: 1901, Birth, 18, V4E10466 (act number: 5571).

[24] Paris Civil Registry, Civil status register from 1860 onwards: 1904, Marriage, 18, 18M330 (act number: 2532).

[25] Seine department military recruitment records, Recruitment number registers (1887-1921) Drucker, Jacques, army number 2834, D4R12292.

Français

Français Polski

Polski