Jacques HALIMI

The Halimi family: from Algeria to Auschwitz

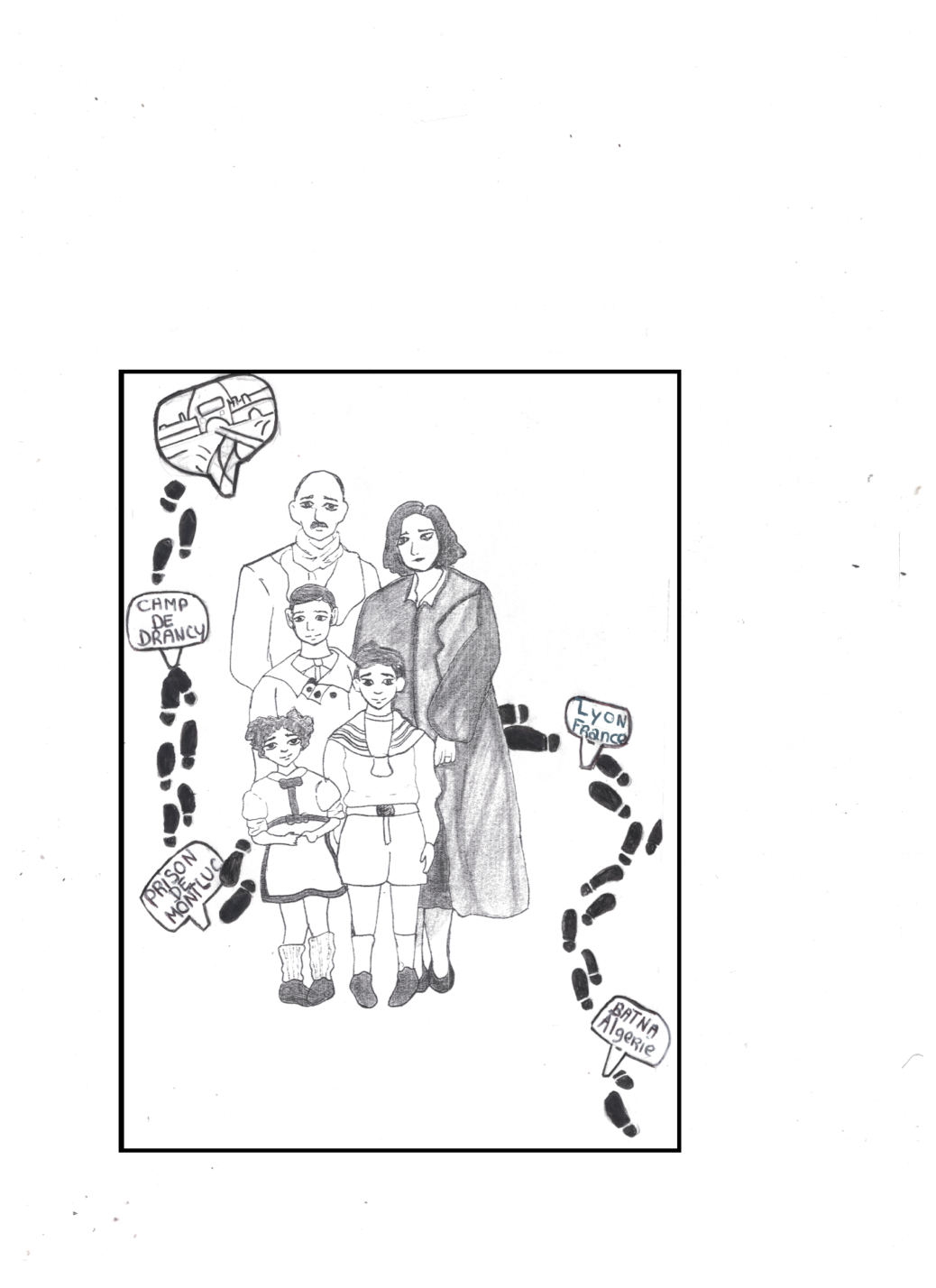

A family’s journey through the Holocaust

By the 9th grade students of class 3e2

at the Michel-Richard Delalande middle school

in Athis-Mons, France

Preface

For the fourth consecutive year, a class of 9th graders from the Michel-Richard Delalande middle school took part in the European project Convoy 77, the aim of which is to write the biographies of the 1,310 people who were deported from Drancy camp and Bobigny railroad station to Auschwitz-Birkenau on July 31, 1944.

Continuing our personal and micro-historical approach[1], we guided the students over the course of the school year as they wrote the biographies of Adolphe, Fortunée, Claude, Jacques and Josiane Halimi.

Having completed a historical investigation based on multiple archived records, our students wrote the story of this family from Algeria who were deported to the hell of the Nazi camps in the summer of 1944.

The writing of this chapter of history, which involved twenty-five students, did not, however, enable us to answer all of the questions raised during the investigation, since the story of the Holocaust is one in which witnesses, archives and evidence were systematically destroyed. It therefore contains some gaps and ellipses.

In parallel with this written work, the students thought about the contents of the records from an artistic point of view. They made memory boxes and time capsules that address the themes of absence, disappearance and destruction of witnesses, records and evidence. In short, this task helped them to reflect on what the genocide brought about: empty or partially empty boxes. In addition, this creative approach, which involves using the imagination, complements the written work undertaken throughout the year.

Over the course of the school year, Michael Aymard, a video maker, followed up on the work undertaken by the students and conducted several filmed interviews in which he asked them about their perception of the project and the challenges it presented. These interviews led to the release of the first episode.

The second episode focused on a virtual meeting with Daniel Urbejtel, a witness and survivor of Auschwitz-Birkenau, someone we have been inviting to the school for the past three years but who was unable to come to the classroom this year due to the health crisis. In order that the students could still listen to this exceptional testimony, we filmed Daniel Urbejtel and put to him, on video, the questions that the students wanted to ask him.

We would like to thank Daniel for making himself available and for his kindness and trust. We all send him our warmest regards.

We would also like to thank Liliane Rehby, who provided us with the invaluable information and records that were essential for the students to be able to retrace the Halimi family’s journey.

Our thanks also go to Georges Mayer, Serge Jacubert, Véronique Likforman and Laurence Klejman of the association of friends and families of the deportees of convoy 77 and to our colleague Claire Podetti for their unwavering support.

Thanks to the Académie de Versailles and the Essonne Department, both of which sponsor this project.

Finally, thanks to Michael for sharing this adventure with us.

Clément Huguet and Déborah Le Pogam, the supervisory teachers.

Introduction

We are the 9th grade students of class 3e2 and we are proud to have participated in the Convoy 77 project, which aims to have us study history and make us think about the dangers of racism, anti-Semitism and hatred of the other.

Since the beginning of the year, we have been working on the stories of Adolphe, Fortunée, Claude, Jacques and Josiane Halimi, a family that came from Algeria and was living in Lyon at the outbreak of the Second World War.

This period of history and the horror of the Holocaust would change their lives forever. Along with more than 1,300 other people, they were deported to Auschwitz-Birkenau on Convoy No. 77 on July 31, 1944.

The Nazis wanted, through the genocide, to make them disappear altogether. So that they will never be forgotten, we have written their story, which is now before your eyes.

For all of us, this task, which involved a historical investigation of archived records and writing the biographies, was very important. Telling the story of what happened is a way to ensure that we do not forget the mistakes of the past.

Unfortunately, both racism and anti-Semitism still exist today. It is therefore up to all of us to work together to banish them from people’s minds.

Chapter 1

Adolphe Halimi was born on April 2, 1899[2] and Fortunée Rehby was born on February 3, 1902[3] in Batna, a small town in the Constantine department of Algeria, which was at that time a French colony. They both come from Jewish families and were French citizens.

The Jewish families living in Algeria go back a long way (their ancestors may have settled there as early as the 8th century BC). Their story is therefore a long one, but an important turning point was the Crémieux decree of 1870, which granted French citizenship to the 35,000 Jews living in Algeria at the time.

We have no information on how or when Fortunée and Adolphe first met, but we do know that they were married on February 25, 1931 in Batna[4]. Adolphe was at that time a “mailman” and Fortunée was “not working”.

The marriage register also states that Haï Halimi, Adolphe’s father, was a “public letter writer” and that Isaac Rehby, Fortunée’s father, was a “senior attorney’s clerk”. Adolphe’s mother, Messaouda Lévy, and Fortunée’s mother, Semah Péraï, were not working at the time. This information is important because it suggests that both Adolphe’s and Fortunée’s families were well-integrated into the community.

After they were married, Adolphe and Fortunée left to set up home in Lyon, France, perhaps in the same year, 1931. We are not sure about the year, however. Once in Lyon, they lived in an apartment in a small building at 5 Place de la Baleine.

On November 30, 1932, a year after they settled in Lyon, they had their first child: Claude[5]. He was followed by Jacques, who was born on December 17, 1935[6].

On May 22, 1938, they had a daughter, Josiane, but unlike her brothers, she was born in Batna, Algeria[7]. Perhaps at that time of year, Adolphe and Fortunée were away visiting their families in Algeria, or perhaps they simply wanted her to be born in Algeria. We do not really know.

In Lyon, Claude, Jacques and Josiane went to the Gerson elementary school. In a class photo taken in 1943-1944, Claude is in the second row. He looks happy and proud to be at school with his classmates. He is posing for the camera with a big smile on his face.

Class photo, taken during the 1943-1944 school year. Claude Halimi is in the second row, fourth from the left. Source: Documentation Center on the Deportation of Jewish Children from Lyon.

Claude was in a boys’ class in elementary school while his little sister Josiane was in a mixed class in kindergarten.

In another class photo, also taken in 1943-1944, we also see Josiane Halimi. She is smiling, looking directly at the photographer, and has her hair is done up in a little bow, as do many of the other little girls.

On her right is her classmate, Josiane Navarro, who gave her testimony to the Documentation Center on the Deportation of Jewish Children in Lyon (CDDEJ) in 2020[8].

Class photograph, taken during the 1943-1944 school year. Josiane Halimi is in the fourth row, third from the right (shown by the arrow). Source: Josiane Navarro / Documentation Center on the Deportation of Jewish Children from Lyon.

In her testimony, she explained that Josiane Halimi was her “favorite little girlfriend in kindergarten” and recalls how disappointed she was when her classmate did not come back to school in September 1944. She described her as a happy little girl who taught her new songs that she had learned from her brothers, Claude and Jacques.

She also said that Fortunée Halimi liked her first name, Josiane, so much when she was born in April 1938 that she wanted to call her daughter by the same name a month later.

Indeed, Ms. Navarro also said that in the Saint-Jean district, which is now called Vieux-Lyon (Old Lyon), there was a vibrant community and that all the families knew each other.

The Gerson school registers provide interesting information about the parents, Adolphe and Fortunée[9]. On Claude’s enrollment form in 1938-1939 and that of Jacques in 1941-1942, Adolphe Halimi is listed as a “mailman for the PTT” (the French postal service), whereas on Claude’s enrollment form for the school year 1943-1944, he is listed as a “pharmacy employee”. He was most likely dismissed from his job with the postal service due to the Vichy regime’s anti-Semitic legislation, and therefore had to change his job. As for Fortunée, we know that she was a homemaker throughout this period, although the records all describe her as “unemployed”.

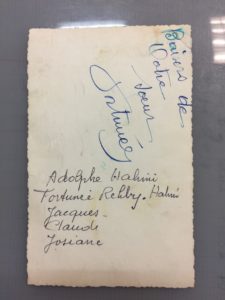

We have only one photograph of the whole family together. It is not dated but it was taken outdoors, in front of a garden, perhaps in Lyon. The three children are in front of their parents. The expressions on their faces are very different: Adolphe seems serious, looking at the photographer with his hands holding Claude’s shoulders, while Fortunée seems more guarded, perhaps more anxious. The children are smiling and appear mischievous. Josiane is wearing a little dress and Jacques is wearing a sailor suit.

On the back of the photo there is an inscription: “Kisses from your sister. Fortunée”. This suggests that Fortunée sent it to her family in Algeria. It was perhaps intended for her brother, Maurice Rehby, who moved to France, more specifically to Bourg-le-Comte in the Saône-et-Loire department, where he became a teacher as from 1936[10].

The inscription on the back is at the top, on the right in the photo below. The names were added later.

Photograph of Adolphe, Fortunée, Claude, Jacques and Josiane Halimi. Date and place unknown.

On the back of the photograph, it reads “Kisses from your sister. Fortunée”. The names below were added later.

Source: Rehby family archives.

Chapter 2

May 1940 marked the beginning of the attack on France by Nazi Germany, after several months of war spent without any actual fighting (the “phoney war”). The German army invaded France quite quickly and, when he was appointed head of government, Marshal Philippe Pétain announced that he was asking for an armistice in a message broadcast on the radio on June 17, 1940. The armistice was finally signed on June 22, 1940 and, just a few days later, Philippe Pétain turned France into a dictatorship: this was the birth of the French state.

A few months later, on October 24, 1940, Philippe Pétain and Adolf Hitler met in Montoire-sur-le-Loir in the Loir-et-Cher department to discuss the situation. This meeting symbolized the state collaboration that Marshal Pétain set up with Nazi Germany.

It was also in October 1940 that the “first statute of the Jews” was drawn up and enforced in France. This decree, directly derived from the Nuremberg Laws passed in 1935 by the Nazi regime, defined Jews from a racial point of view: any person with at least three Jewish grandparents was deemed to be Jewish.

This decree also took away much of the Jews’ freedom. It forbade them from entering certain public places and from working in several professions, such as the civil service.

As of June 2, 1941, it became mandatory for all Jewish people throughout France to take part in a census, which enabled the police to gather their addresses and information about their family members.

As a result, Maurice Rehby, Fortunée Halimi’s brother, wrote a “declaration of Jewish race” in which he declared that he “was considered to be of Jewish race, according to the law of June 2, 1941,” but also specified that he “was a Catholic prior to June 25, 1940,” that he was “married to a non-Jewish woman” and that he had “two non-Jewish children”[11].

This document also tells us that Maurice Rehby was a schoolteacher but that following the “first status of the Jews”, he had been relieved of his duties on December 20, 1940. He could no longer teach his students because he was deemed to be Jewish. This is confirmed by his teacher’s service record, which is kept in the Saône-et-Loire departmental archives[12].

The 8th German decree, issued on May 29, 1942 made it compulsory for all Jews over the age of six in the northern, occupied zone to wear a yellow star. The reason for this symbol was to distinguish Jews from other people in order to better discriminate against them.

We did not see any yellow stars in the photographs of the Halimi family that we examined. In fact, since the city of Lyon was in the southern, free zone, it was not compulsory for Jews to wear a yellow star. On the other hand, they did have to have a stamp saying “Jew” on their identity cards (decree dated December 11, 1942). We do not know if the Halimi family’s identity cards had this stamp or not. It is difficult to retrace their history accurately during this period.

We do know, however, that Maurice Rehby was involved in the Resistance, more specifically in the FFI, the Forces Françaises de l’Intérieur (French Forces of the Interior) of the Saône-et-Loire department. He was in the Marcigny Maquis (Resistance group) from February 1944 to September 1944. An FFI membership certificate was drawn up in September 1949[13].

We do not know if Fortunée knew about her brother’s involvement in the Resistance. Perhaps he felt he could not tell her because he did not want to put her in danger.

Meanwhile, Fortunée and Adolphe Halimi asked for help from the Swiss Red Cross’ Children’s Relief fund, to sponsor one of their children. We know that Claude was sponsored in May and June 1944 (the sum of 250 francs was paid each time): a letter received by Fortunée confirms this, as does a sponsorship card[14]. This shows that despite the difficulties and persecution, the parents tried to find solutions to make their children’s lives a little easier.

Chapter 3

On January 20, 1942, at the Wannsee conference, the Nazis agreed to implement the “final solution to the Jewish question” throughout Europe. They decided to systematically exterminate all the Jews in Europe.

From July 1942 onwards, roundups and mass arrests, sometimes involving an entire neighborhood, became more and more frequent in France. For example, on July 16 and 17, 1942, the Vichy regime organized a huge roundup in Paris at the request of Nazi Germany, deploying more than 9,000 French police and gendarmes. 13,152 people (including more than 4,000 children) were arrested and detained for several days in appalling conditions in a Paris cycling track called the Vélodrome d’Hiver, after which they were sent to the Auschwitz-Birkenau killing center in Poland.

In Lyon, as in other large French cities, arrests also took place routinely from 1942 onwards. For example, on February 9, 1943, the Gestapo, the Nazi political police, arrested 86 people during a round-up in rue Sainte-Catherine.

There were other mass arrests in the Lyon area, for example at Izieu on April 6, 1944, where 44 children and 7 adults were arrested. Throughout this period, there were also many arrests that targeted one or more families in smaller towns and villages.

On July 8, 1944, the Halimi family was swept up in the horror. In a written testimony addressed to a police commissioner in 1950, Maurice Rehby recounted that day in July[15]. On July 8, 1944, the Halimi family was swept up in the horror. In a written testimony addressed to a police commissioner in 1950, Maurice Rehby recounted that day of July 8[15]. 15] Adolphe Halimi, his wife Fortunée, and their three children, Claude, Jacques, and Josiane, were at home at 5 Place de la Baleine in Lyon. The police burst into the small building, knocked on their door, and asked them to follow them right away, and with that, they were arrested. We do not know if the family was targeted specifically, or if the police were looking for one or several other families in the building or in the neighborhood.

That day, a little boy aged 6, who was born in Luxembourg, happened to be at the Halimi house: he was called Edmund Sandmann.

His mother, Hena, and father, Moses, had been arrested a few months after they arrived in France in 1941. Both were interned in the Rivesaltes camp in the Pyrénées Orientales department. Hena was deported in September 1942 but we do not know what became of Moses[16].

Initially interned at Rivesaltes, Edmund was then placed in children’s homes run by the OSE (Oeuvre de Secours aux Enfants, Children’s Aid Society), including the Château de Chabannes in Saint-Pierre-de-Fursac in the Creuse department, and then in foster families[17].

He had only arrived in Lyon the day before the arrest and was staying the night with the Halimis, after which he was to be smuggled across the border into Switzerland[18].

Sadly, he was arrested at the same time as the Halimi family, as confirmed by the testimony of René Allouche[19], a friend and neighbor, who stated that “a child entrusted to his care” had been arrested at the same time as the family. Several other administrative records also mention that there were four children in the Halimi family.

Might Adolphe and Fortunée have been in contact with a network that smuggled children into Switzerland, or did they agree to help a little orphan boy just the once? We do not know for sure.

Immediately after they were arrested, the parents were locked up in the Montluc prison in central Lyon. It was a transit facility and the gateway to the whole concentration camp system. The cells were tiny: they were only about 43 square feet each and meals were few and far between. As time went on, more and more people were taken to Montluc: 1,300 were detained there at the beginning of 1944. All the other spaces, apart from the cells, were gradually converted into accommodation: the showers, the toilets and the workshops. A large wooden hut in the prison courtyard was known as the “Jewish hut” and was used to hold mainly Jewish men over the age of 15[20].

Given that Montluc was so overcrowded, the Halimi and Edmund Sandmann children were interned, without their parents, in the Antiquaille hospital in Lyon, which in February 1944 had been converted into a detention center for Jewish children rounded up by the Gestapo and the French collaborators.

We can only imagine how heartbreaking it must have been for the parents who were separated from their children and did not know if they would ever see them again. At the Antiquaille hospital, social workers from the UGIF, the Union Générale des Israélites de France, or Union of French Jews took care of the children. This was true, for example, of Irène Cahen, who kept a list in a little notebook in which she noted the names of all 75 children she cared for from February 4, 1944 to August 17, 1944. The names of Claude, Jacques, Josiane and Edmund appear in it, and we thus have proof that the children were indeed held in this hospital from July 8, 1944 to July 22 1944[21].

In the Antiquaille hospital register, a blue dot was added next to their names: this meant that they were being held there until they were deported.

Between July 22 and 24, 1944, the parents, the three children and Edmund Sandmann were all taken to the Paris area and interned in Drancy camp. Once there, they found a U-shaped housing development that was still under construction, as it had been left unfinished before the war. Converted into an internment camp, it was guarded by French police and surrounded by barbed wire, watchtowers and fences. The living conditions were very harsh. There were no facilities in the buildings and only one water point was available[22].

When they arrived at Drancy, they were first sent to the search barracks in the courtyard. This is where they were checked in and issued with internment cards with identification numbers, ranging from 25.824 to 25.829 for the Halimi family and little Edmund Sandmann[23].

Their personal belongings were also confiscated, in particular valuables. Money, jewelry and a few other items were taken from Fortunée and Adolphe, according to the records of the search logs kept at the Shoah Memorial. They had probably taken them with them when they were arrested in Lyon.

In the camp, Adolphe was first placed in staircase 9, room 3, and then in staircase 5, room 4. Fortunée, Claude, Jacques, Josiane and Edmund were all initially put in staircase 5, room 1, and then in staircase 4, room 3.

Chapter 4

On July 31, 1944, the Halimi family and Edmund Sandmann were deported on Convoy No. 77 from Drancy-Bobigny[24]. The convoy was put together the day before the deportation and then, early in the morning, buses took the internees from Drancy camp to the Bobigny railroad station.

When they got there, the 1,310 people are crammed into cattle cars bound for the Auschwitz-Birkenau killing center in Poland. Children were crying and screaming. Some of the internees found it hard to climb into the wagons because the steps were so high[25].

The journey lasted several days and the travelling conditions were extremely difficult. It was the height of summer and the weather was very hot that year. There were so many of them that they they were forced into awkward and uncomfortable positions. There was barbed wire over the tiny windows, very little ventilation and only one bucket of water at one end of the car. The train stopped regularly, but only after several days did the doors finally open at Auschwitz-Birkenau killing center. The deportees did not know where they were.

Adolphe, Fortunée, Claude, Jacques, Josiane and Edmund found themselves surrounded by chaos: they could hear screaming, yelling and aggressive orders from the Nazis, as well as dogs barking. They had to hurry and abandon all their belongings. It was a terrifying experience.

While they were still on the platform, the Nazis carried out the selection of the deportees. They looked briefly at their physical characteristics and decided whether or not they were suitable for forced labor. They put the deportees in two separate lines. The adults, mainly healthy-looking men, were usually selected for forced labor, but it was not always that clear-cut.

Daniel Urbejtel, for example, who was deported on the same convoy, was deemed fit for work although he was only 13 years old. ”My brother was sent to the men’s side. And, against all the odds, I too was sent to the men’s side. One thing is for sure: if I had been free to choose which line to be in, I would have chosen the children’s side”. [26]

It is at that point, on the ramp at Auschwitz, that the Halimi family was separated forever.

Fortunée and the children were sent to the line of deportees unfit for work. Their fate was sealed: they were to be murdered the same day in the gas chambers at the far of the camp. They were sent to a place that seemed to be a communal shower room. However, when the doors closed, a deadly gas called Zyklon B was released into the room. All the deportees died of asphyxiation. Other deportees, the Sonderkommandos, then removed the bodies and burned them in crematoria.

On the platform at Auschwitz-Birkenau, Adolphe was selected to work. For the next few months, he lived in atrocious conditions. There was not enough food and it was very basic, just bread and water. The deportees’ clothing was not suitable for work or for the winter, which could be very cold in Eastern Europe. The sanitary conditions were also inadequate and the deportees were almost always covered with mud, dirt and sweat. Such an environment gave rise to illnesses that were easily spread. On the rare occasions that they were allowed to take showers, they were afraid that they were gas chambers. Rest times were short and the work seemed never ending, was always very hard and involved earthworks, for example.

Sometimes the work was utterly useless and was intended only to cause the deportees psychological distress.

Adolphe endured these difficult conditions for several months, first in Auschwitz-Birkenau, and then in other camps. The Nazis decided to transfer him, along with many other deportees, as the Soviet army was advancing westward in 1944 and 1945. He was first moved to the Stutthof camp, near Danzig, in Poland, and then to the Struthof camp in Natzweiler, near Strasbourg[27].

In November 1944, he was in the Echterdingen annex camp in Germany and his last transfer was to the Vaihingen annex camp, also in Germany. Working and living conditions were once again appalling and illnesses spread rapidly. According to the records, Adolphe died of exhaustion there on March 15, 1945[28].

On December 19, 1945, a neighbor of the Halimi family in Lyon, a Ms. Demay, wrote to the wife of Maurice Rehby, Fortunée’s brother, who was looking for information. In her letter, she wrote the words: “The people deported at the same time as Madame Halimi have, like her, vanished without a trace of their stay on earth. It is as if a huge trap door opened up in the bowels of the earth and swallowed up all these human lives, so that only memories and regrets are left in the hearts that mourn them[29].

Postface

In parallel with the historical investigation and written work that we began at the very beginning of the school year, we made time capsules using archive boxes and glass jars.

Prior to the this, our teacher introduced us to a book that both amazed and impressed us: It was called Notre Combat (Our Struggle), compiled by Linda Ellia and published in 2007.

In it, artists and others used Adolf Hitler’s Mein Kampf (My Struggle) as the basis for many different pieces of work. The original text is no longer readable and has been used as a medium for pieces that oppose, erase and transform the original Nazi ideology.

We were all very surprised by this approach and by the incredible number of drawings and creations that are included in the book.

We in turn thought about the records that we used in our historical investigation and how we might interpret or showcase them.

The work was carried out in the same groups as the historical investigation so that everyone could make the best use of the records we had.

We started by brainstorming and thinking about the techniques we wanted to use. Then, over the course of several sessions, we created our designs.

It was a very interesting exercise for us because it was an alternative way of thinking about how to make use of the records. We are happy that our creations feature in this biography.

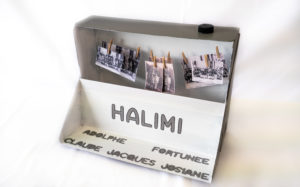

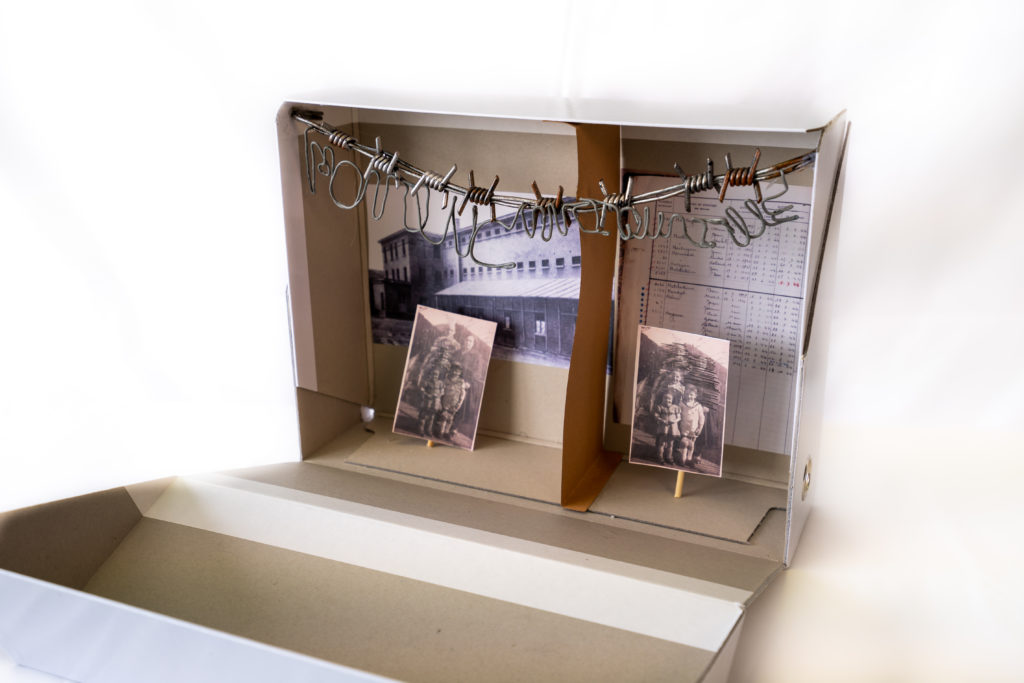

The front and inside of the box.

Our archive box represents a camera in which we have recreated a photographer’s studio. In it, we hung the photos of Adolphe, Fortunée, Claude, Jacques and Josiane Halimi that we worked on. It was very important for us to showcase these photos because they depict the Halimi family’s life prior to the war and before the Holocaust.

LUNA, FATOUMATA, WAIL AND ABDELMALEK

To make our time capsule, we chose to work with a glass jar.

We have put yellow stars inside, some on the bottom and some hanging on transparent thread. These symbolize the persecution and discrimination that the Jews suffered during the Shoah.

On the sides of the jar, we stuck passages from the “declaration of Jewish race” written by Maurice Rehby, Fortunée Halimi’s brother. We were very moved by this document during our investigation and it is, for us, representative of the racist and anti-Semitic ideology adopted by the Vichy regime in France during the Second World War.

SHANEL, HAKIMA, CRISTIANO, ANISS AND ALMAMI

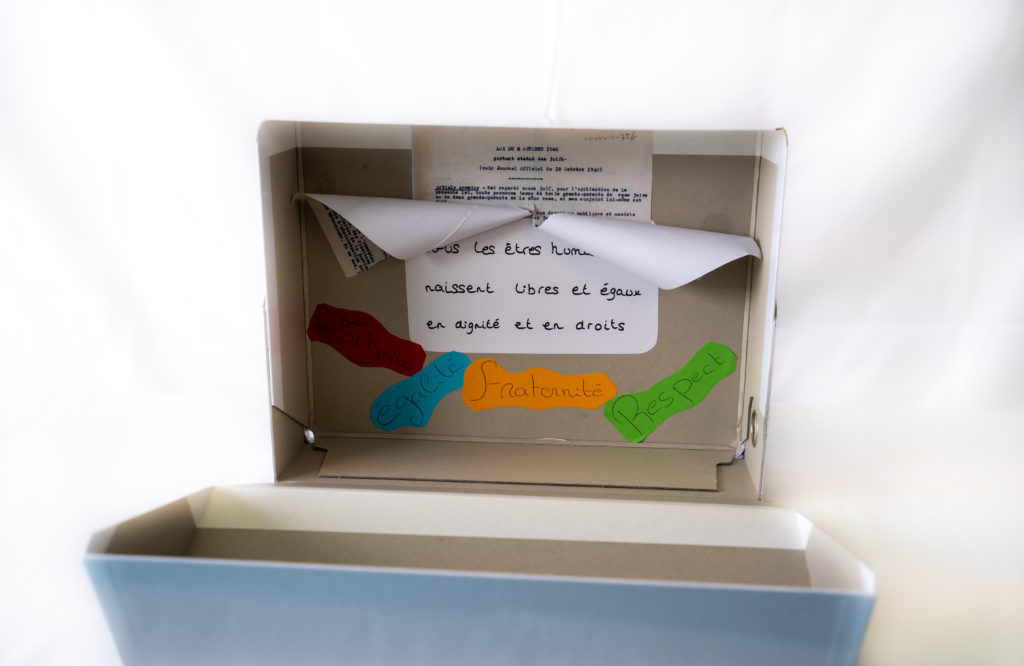

For our second piece, we decided to work with an archive box. We began by using the first page of the decree dated October 3, 1940, also known as the “First Statute of the Jews”. Article 1 of this law uses the same racial definition of Jews as the one used by the Nazis in the 1935 Nuremberg Laws.

We stuck this inside the box but tore it up, leaving only the top section, with the title and the first article, visible. Next, we placed the first article of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights below it to convey a message of hope and to remind us that “all human beings are born free and equal in dignity and rights”.

Lastly, we wrote the words “Liberty”, “Equality”, “Fraternity” and “Respect” on colored paper and glued those too inside the box.

SHANEL, HAKIMA, CRISTIANO, ANISS AND ALMAMI

In this archive box, we wanted to recall that following their arrest in Lyon in July 1944, the Halimi parents and children were separated: the parents were locked up in the Montluc prison while the children were taken to the Antiquaille hospital, which at the time had been partially converted into a detention facility.

To illustrate this separation, we divided the box in two. On the left, we glued in a photo of Montluc prison and, in front of that, we added a photo of the family in which we cast a shadow on the children. On the right, we put an excerpt from the register showing that the children were sent to the Antiquaille hospital. In front of it, we put the same photo of the Halimi family but this time with the parents shaded in.

Lastly, we strung a length of barbed wire across the box. This, for us, symbolizes the incarceration of the Halimi family. We then added the words “Montluc” and “Antiquaille” made out of wire.

SHAYNA, CHAD, KAILYS, BEATRIZ AND VALENTIN

In this jar, we wanted to depict the Halimi family’s deportation to Auschwitz-Birkenau. Rails, which we made, were placed at the bottom of the jar and we then hung the names of several people who were deported on Convoy 77. On the sides of the jar, we glued the Halimi family photograph and at the top we glued some cotton wool which symbolizes the clouds, the sky and death, given that none of the family survived the camps.

FAYROUZ, DIOGO, ROKIA, JOVANA AND ERICA

This archive box represents the deportation to Auschwitz-Birkenau. We decided to paint the inside of the box black, to symbolize death. At the bottom, on railroad tracks, we put two cattle cars, onto which we stuck sections of the Convoy No. 77 deportees list including the names of Adolphe, Fortunée, Claude, Jacques and Josiane. At the top, we put the Halimi family photograph between two black light bulbs, which represent the darkness in the cattle cars in which the deportees were taken to Auschwitz.

FAYROUZ, DIOGO, ROKIA, JOVANA AND ERICA

This project was sponsored by the Versailles Education Authority and the Essone department.

In the summer of 1944, the lives of Adolphe, Fortunée and their three children Claude, Jacques and Josiane were changed forever.

Originally from Algeria and having lived in Lyon since the 1930s, they were arrested in their own home and deported to the Auschwitz-Birkenau killing center on Convoy 77.

This biography retraces their journey and tells their story, so that they will never be forgotten.

Wail, Shayna, Fayrouz, Diogo, Aniss, Fatoumata, Kailys, Shanel, Rokia, Almami, Erica, Lilko, Luna, Abdelmalek, Jovana, Inès, Nanding, Chad, Cristiano, Sydra, Beatriz, Hakima, Anrif, Valentin and Gaye

[1] Claire ZALC, Tal BRUTTMANN, Ivan ERMAKOFF and Nicolas MARIOT (dir.), Pour une micro histoire de la Shoah, Seuil, « Le genre humain », 2012.

[2] Adolphe Halimi’s birth certificate. Victims of Contemporary Conflicts Archives Division of the Ministry of Defense Historical Service, in Caen, dossier n°15.688, ref. AC 21P 461270.

[3] Fortunée Halimi’s birth certificate. Victims of Contemporary Conflicts Archives Division of the Ministry of Defense Historical Service, in Caen, dossier n°15.684, ref. AC 21P 461275.

[4] Excerpt from the marriage register of the municipality of Batna, Algeria. Victims of Contemporary Conflicts Archives Division of the Ministry of Defense Historical Service, in Caen, dossier n°15.688, ref. AC 21P 461270.

[5] Claude Halimi’s birth certificate. Victims of Contemporary Conflicts Archives Division of the Ministry of Defense Historical Service, in Caen, dossier n°15.686, ref. AC 21P 461272.

[6] Jacques Halimi’s birth certificate. Victims of Contemporary Conflicts Archives Division of the Ministry of Defense Historical Service, in Caen, dossier n°15.685, ref. AC 21P 461274.

[7] Josiane Halimi’s birth certificate. Victims of Contemporary Conflicts Archives Division of the Ministry of Defense Historical Service, in Caen, dossier n°15.687, ref. AC 21P 461276.

[8] See https://www.deportesdelyon.fr/les-archives-par-famille-a-m/enfants-halimi-2

[9] Enrollment registers from the Gerson school in Lyon. Lyon Municipal Archives, ref. 2307W/2.

[10] Maurice Rehby’s record of service as a teacher. Saône-et-Loire Departmental Archives, ref. 3T1177.

[11] Maurice Rehby’s “Declaration of Jewish Race”. Saône-et-Loire Departmental Archives, ref. 1W452.

[12] Maurice Rehby’s record of service as a teacher. Saône-et-Loire Departmental Archives, ref. 3T1177.

[13] Membership certificate of the French Forces of the Interior (FFI). Ministry of Defense Historical Service in Vincennes, ref. GR 16P 503692.

[14] Rheby family archives.

[15] Maurice Rehby’s testimony from 1950. Victims of Contemporary Conflicts Archives Division of the Ministry of Defense Historical Service, in Caen, dossier n°15.684, ref. AC 21P 461275.

[16] According to Laurent Moyse, La tragique odyssée du jeune Eddy (The tragic odyssey of young Eddy), Die Warte, Luxemburger Wort, June 13 2019, pp. 6-7.

[17] According to the Shoah Memorial archives.

[18] You can read the complete biography of Edmund Sandmann, written by Laurent Moyse, here: https://en.convoi77.org/deporte_bio/edmund-sandmann/

[19] Yad Vashem testimonial sheet (see https://www.deportesdelyon.fr/les-archives-par-famille-a-m/enfants-halimi-2).

[20] See http://www.memorial-montluc.fr/

[21] See the excerpts from Irène Cahen’s notebook: https://www.deportesdelyon.fr/les-archives-par-famille-a-m/enfants-halimi-2

[22] See Annette WIEVIORKA, Auschwitz expliqué à ma fille (Auschwitz explained to my daughter), Seuil, 1999, p.22.

[23] Registration sheets for Adolphe, Fortunée, Claude, Jacques, Josiane Halimi and Edmund Sandmann drawn up at the Drancy camp on July 24, 1944. French National Archives / Shoah Memorial. Drancy registration sheets for adults F9/5699 and for children F9/5744.

[24] Excerpt from the deportation register of Convoy 77, Shoah Memorial.

[25] Testimony of Daniel Urbejtel, Auschwitz survivor, collected in December 2020.

[26] Testimony of Daniel Urbejtel, Auschwitz survivor, collected in December 2020.

[27] Excerpt from the register of prisoners of the Natzweiler concentration camp. Arolsen Archives – ITS.

[28] Extract from the death register of the Wiesengrund subcamp, near Vaihingen. Arolsen Archives – ITS.

[29] Rheby family archives.

Contributor(s)

The 9th grade students of class 3e2 at the Michel-Richard Delalande middle school in Athis-Mons, France.

Français

Français Polski

Polski