Jeanne MOHA (1925–1998)

Deported at the age of 19 on the same convoy as her parents and brothers, all of whom were killed, Jeannette Secaz, née Moha, lived through her experiences in Auschwitz and returned home to France. This is the story of a survivor.

Jeanne Moha was born at 4 a.m. on April 5, 1925 at her parents’ home at 31 rue des Nonnains d’Hyères in the 4th district of Paris. It was in the Marais quarter, which was home to a sizeable Jewish community. Her parents, Charles and Zina (née Djian) Moha, were married in Algiers in 1915, while Charles was serving in the army. They named their little daughter Félicie Jeanne, but as she grew up, she chose to use the name Jeanne, and her close friends and family called her Jeannette.

Charles and Zina already had a daughter, Berthe, who was born on April 24, 1920, and a son, Marcel, born on November 10, 1921. Both were born in Algiers, in Algeria. Charles was a signwriter and Zina a homemaker. When they first arrived in Paris, although we do not know exactly when that was, the family opened a little grocery store on rue du Roi de Sicile in the Marais. Around two years later, on April 13, 1927, the family expanded again when another son, Roger, was born.

The following year, in 1928, the family moved to 13 rue Abel in the 12th district of Paris. In 1931, by which time she was 6, Jeanne started at the nearby Charles Baudelaire elementary school for girls. She left in March 1938 having passed her school leaving certificate. The school register states that after she left, “she stayed at home”. She may well have gone on to train as a typist, as this is the occupation listed in later records.

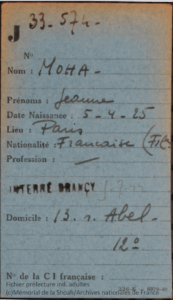

By October 1940, a little over a year after the outbreak of the Second World War, Jeannette was 15. Together with the rest of her family (records for them can no longer be found, however), she had to take part in a census of the Jews. Although there is no occupation listed on her registration form, which is blue, she appears to have worked as a secretary for a copy-printing firm prior to her arrest. On October 7, the Vichy government repealed the Crémieux decree, which, since 1870, had granted Algerian Jews French nationality[1].

Jeannette’s census form

Jeannette in 1943 or 1944, before she was deported

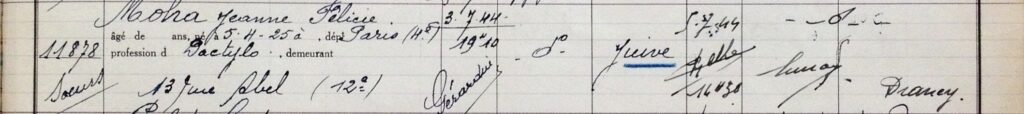

On July 3, 1944, the Gestapo arrested Jeannette, who was 19 by then, along with her younger brother, Roger. It would seem they were on their way home from an afternoon at the local pool. If so, they were breaking the German order that banned Jews from various public places, including swimming pools[2]. The arrest report states that the siblings arrived at the Paris police headquarters detention center at 7.10pm. and that they were brought in by police officers acting on behalf of the “Jewish Affairs” department. Jeannette was then handed over to some nuns who were responsible for watching over female prisoners. They were released two days later, on July 5, and transferred to the Drancy camp.

Arrest record

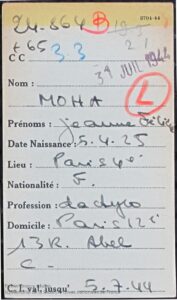

When Jeannette arrived in Drancy, she was assigned prisoner number 24864 and then interned in room 3 on staircase 19, not far from Roger, who was put in room 4. The form completed when she arrived in the camp reveals that she had been working as a shorthand typist.

Drancy record form

Jeannette’s parents, her brother Marcel and his fiancée, Colette, were all arrested three weeks later, on July 27, as a result of a tip-off from someone who knew them. Shortly afterwards, they too were interned in Drancy. By chance, Berthe, her eldest sister, managed to avoid being arrested, and went into hiding with a neighbor for a while.

DEPORTATION

On July 31, 1944, 1309 of the people interned in Drancy were put on buses, taken to Bobigny railroad station and hastily loaded onto a waiting train. At 8 o’clock in the morning, the whistle blew and Convoy 77 set off for Auschwitz.

We know from a number of survivors’ accounts that the travelling conditions during the journey were appalling. The deportees were crammed into cattle cars, the sanitary conditions were abysmal (there was just a tin bucket by way of a toilet), and there was not even enough room for people to sit down. Eventually, in the early hours of August 3, the train arrived in Auschwitz-Birkenau, the doors were flung open and the deportees were met with glaring spotlights and SS men shouting orders in German, their dogs barking furiously. They had to jump or scramble out of the carriages and line up as fast as they could, men on one side, women and children on the other. The selection process began immediately. Jeannette later recalled “that day, it was the infamous Josef Mengele[3][4] who decided the fate of the deportees”. The less-able people (seniors, sick and disabled people, women with babies or small children, and anyone else who did not look strong enough to work) were sent straight to their deaths in the gas chambers. Jeannette’s parents, Charles and Zina, were among them.

Jeannette and her brothers were all selected to go into the camp to carry out forced labor, but at that point, they were separated forever. The women’s camp and the men’s camp were in two different places.

Soon after she entered the concentration camp, the number A 16764 was tattooed on Jeannette’s forearm. From that moment on, she no longer had a name: it was replaced by the number. Apart from the number, however, we have no details about the five months she spent in Auschwitz. What type of work did she do ? Which kommando was she assigned to?

In November 1944, five months after she arrived in Auschwitz, Jeannette was transferred to the Kratzau camp in Czechoslovakia, a sub-camp of Gross Rosen. It held about 1000 women of various different nationalities, almost all of whom worked shifts in a nearby ordnance factory. According to Yvette Levy, another Convoy 77 survivor, the train journey from Auschwitz to Kratzau took 3 days and 3 nights. Jeannette stayed there for around 6 months, from November 1944 to May 8, 1945, when the Soviet army liberated the camp.

THE RETURN TO FRANCE AND LIFE AFTER THE WAR

Just under a month later, on June 5, 1945, Jeannette was repatriated to France from the Kratzau camp, arriving first in the reception center in Saint-Avold, just over the German border in the Moselle department of France. Her medical report does not mention any illness, nor does it say anything specific about her state of health, which was described as “average”. Nevertheless, she only weighed 68 pounds. Her son told us that his mother sometimes spoke of how she arrived at the reception center at the Lutetia hotel in Paris, how extremely thin she was, how she was examined briefly by a doctor and then given a subway ticket to make her own way home. She then spent some time in a convalescent home in Chamonix in the Alps mountains to regain her strength and put on some weight.

Jeannette in Chamonix in 1945

After that, Jeannette returned to Paris, where she moved back into the family home in the 12th district. Her brothers, Roger and Marcel, never returned from the camps.

On September 5, 1946, around a year after she was liberated, Jeannette married Joseph Szczekacz, an upholsterer, in Paris. The couple moved in with is parents, on rue Abel. They had their first child in 1947.

Jeannette in 1946

In 1953, Jeannette embarked on the formalities that culminated in her being granted “political deportee” status on October 1, 1956. This entitled her, among other things, to a compensation payment based on the number of days during which she was deported. In common with many other deportees, Jeannette spoke very little about that period of her life.

However, her son told us that she became firm friends with Perlette Drai and Germaine Akierman.

In 1957, Jeannette gave birth to a daughter, Ghislaine. Four years later, in 1961, the family moved from rue Abel. Joseph set up his own business as an upholsterer and decorator, and Jeannette worked with him. In 1968, they changed their surname to Secaz.

Jeannette died on June 12, 1998 in Savigny-le-Temple, in the Seine-et-Marne department of France. Aged 73, she left behind numerous grandchildren and great-grandchildren. One of her granddaughters recalls: “My grandmother wore [the perfume] l’Air du Temps. I remember her smile and how she always cheered me up when I was a troubled teenager. And her bracelets that tinkled when she baked her favorite cake. After searching for years, I finally found the recipe. Maybe one day I’ll make it too”.

Notes & references

[1] Although Allied troops landed in Algeria on November 8, 1942, this and the later anti-Jewish discriminatory legislation was not abolished until October 21, 1943. The Crémieux decree was then reinstated.

[2] On May 29, 1942, the German military command issued its eighth order requiring all Jews aged 6 and over in the occupied zone (except Italian, Greek, Turkish and Spanish Jews) to wear a six-point yellow star, also known as the Star of David, “clearly visible” on the left side of the chest. The decree took effect on the morning of June 7, 1942. On July 8, Jews were banned from public places, theaters, cinemas, telephone booths, swimming pools, sporting events and parks, and access to department stores was limited to one hour a day. The star made them easily identifiable as Jews. Cf. Claire Zalc, “L’étoile jaune, histoire d’un stigmate”, (“The yellow star, the history of a stigma”), published in L’Histoire in May 2022. The article is available, in French only, on the l’Histoire website.

[3] Other eyewitness accounts state that it was Dr. Horst Fischer, the camp’s deputy chief physician, who carried out the selection on the ramp in Birkenau.

Sources

- Paris archives (school registers, census data etc.)

- Victims of Contemporary Conflicts Archives Division of the French Ministry of Defense Historical Service, in Caen, dossier no. 21 P 679 385, Félicie Jeanne Moha, married name Szczekacz

- Shoah Memorial, Paris

- Jean Laloum’s, “Des Juifs d’Afrique du Nord au Pletzl ? Une présence méconnue et des épreuves oubliées (1920-1945)” (“North African Jews in the Pletzl? A little-known presence and forgotten hardships (1920-1945”)), published in Archives Juives

- Victims of Contemporary Conflicts Archives Division of the French Ministry of Defense Historical Service, in Caen, dossier no. 21 P 679 385, Félicie Jeanne Moha, married name Szczekacz

- Paris Police headquarters archives, ref. CC2-8

- Photographs kindly provided by Mr. Secaz, Jeannette’s son

- Mr. Secaz’s testimony

Français

Français Polski

Polski