Simone BRONSTEIN

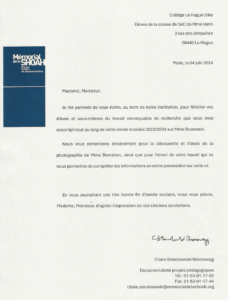

This project was carried out by the 9th grade students from class 3C at the Hague Dike middle school in Beaumont-Hague in the Manche department of France: Joseph Renard, Eudoxie Sulpice, Louis Renouf, Romane Soinard, Dimitri Launay, Honorine Varin and Yanis Henry.

Over the course of the year, some other students joined the project: Paul Rollo, Fabien Crestey, Jeanne Chanu, Maddy Dorey and Noémie Enquebecq.

Their teacher, Ms. Cécilia Varin, wanted to teach the subject of the Holocaust in a different way, by delving into the life story of one particular woman, Simone Bronstein, and her family: to put a face and a story to a name.

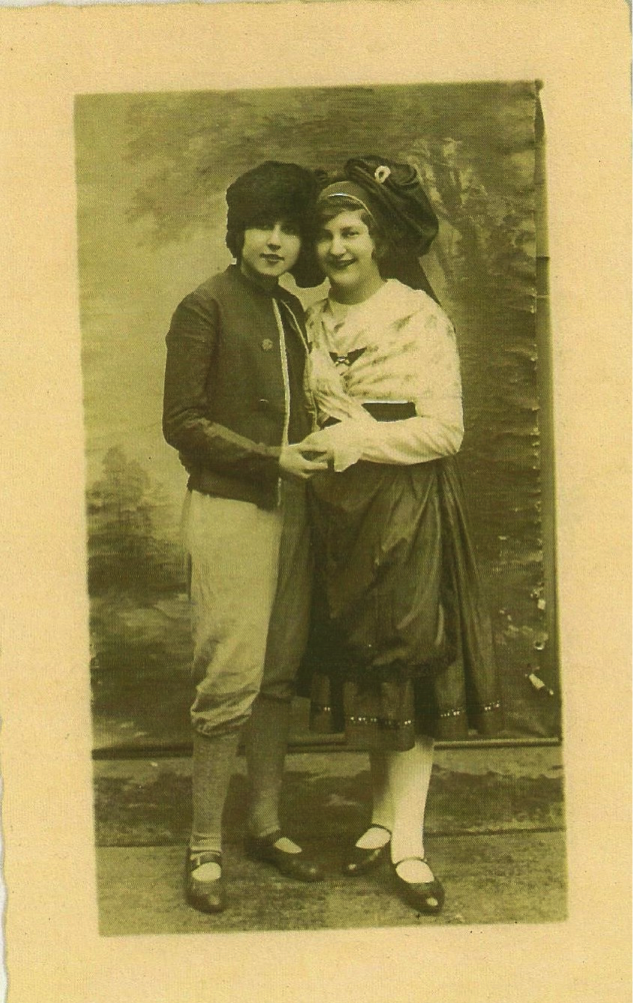

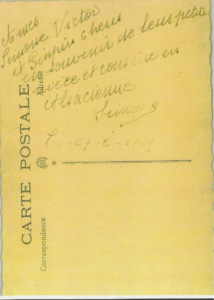

A postcard that Simone sent to her relatives. She is pictured with a young woman called Hélène (who we have not been able to identify). Simone, aged 13, is wearing a traditional outfit from Alsace.

The back of the postcard, on which she wrote: “To my beloved Simone and Victor and Pimpins (Simone’s cousin Serge and Jacqueline, Simone’s aunt’s sister, who was born in 1913 and often took care of Serge), as a memento of their great niece and cousin from Alsace. Simone”.

I) Introduction to Simone’s family

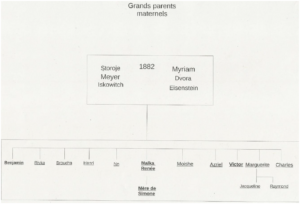

1. The maternal side of the family

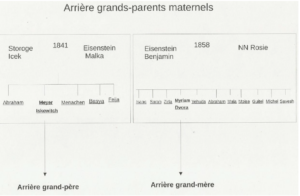

Both sides of Simone’s great-grandparents were born and lived in Ukraine (which was then in the Russian Empire). Meyer Iskowitch Storoge’s parents were Icek Storoge, who was a shoemaker, and Malka Eisenstein.

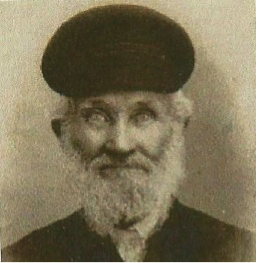

Icek Storoge

Myriam Dvora Eisenstein’s parents were Benjamin and Rosie Eisenstein

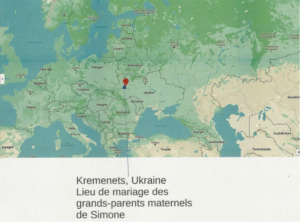

Storoge Meyer Iskowitch and Myriam Dvora Eisentein were Simone’s maternal grandparents. They were married in Kremenets, Ukraine, in 1882.

Simone’s mother was called Malka Renée Storoge. She was the sixth child in the family. She was born on December 20, 1893 at 20 or 22 rue de la Goutte d’Or in the 18th district of Paris, which turned out to be vitally important later on in life because it entitled her to become a French citizen.

Simone’s mother’s birth place in the 18th district of Paris

There were eleven children in the family, some of whom were born in Paris while others had been born the Russian Empire. This may well have been due to the political climate at the time.

In the 1880s, Simone Bronstein’s maternal grandparents lived in a shtetl in Kremenets. Shtetls were small Jewish towns or villages in Eastern Europe. They were closely-knit communities with their own cultural and religious traditions.

Photo of a shtetl in Kremenets in 1921. Source: My Shtetl.org

Photo of the Synagogue Choir in 1912. Sobol family archives

On March 13, 1881, a group of revolutionaries attacked Tsar Alexander the Second’s carriage. The emperor died, and his successor, Alexander the Third, immediately launched an anti-Semitic campaign, which in turn led to a series of pogroms.

The word pogrom, from the Russian “to destroy everything”, refers to an unlawful and violent attack on a community or an individual, and in particular on the Jews in the Russian Empire. It describes an anti-Semitic frenzy of murder, pillage and rape. The first spate of pogroms took place in April 1880 in the towns and cities of present-day Ukraine. These pogroms were led by peasants, manual workers and townsfolk. Alexander the Third’s government then put its anti-Semitic policy into practice by stripping Jews of their businesses and social status.

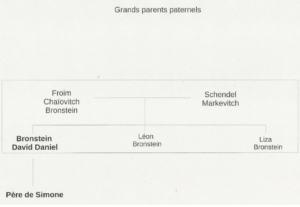

2. The paternal side of the family

We have no information about Simone’s paternal great-grandparents, and very little about her paternal grandparents. We do know that her grandfather, Froïm Chaïovitch Bronstein, was born in Paris, as was her grandmother, Schendel Markevitch. They were both traders and lived at 52 rue des Vinaigriers in the 10th district of Paris.

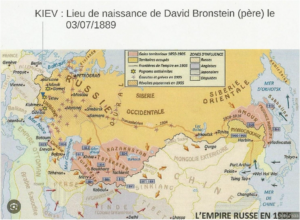

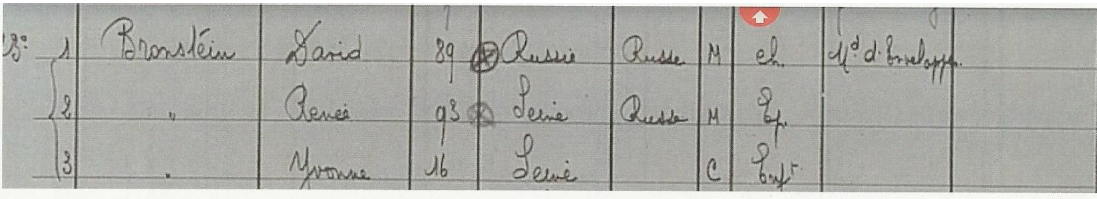

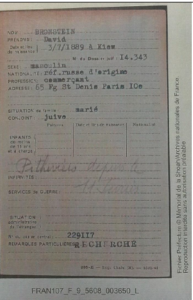

Their children were David Daniel Bronstein, who went on to become Simone’s father, Léon Bronstein, who was born in 1887, and Lisa Bronstein, born in 1884. David was born in Kiev, in present-day Ukraine, on July 3, 1889. This proved to be a serious problem for him during the Second World War, as he was not a French citizen.

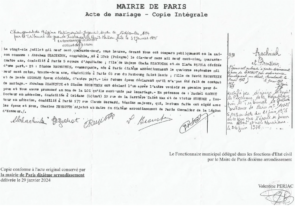

3. Simone’s parents’ wedding

Renée and David met in Paris and were married on May 7, 1914.

Source: French National Archives, Paris (online)

The wedding took place in the town hall of the 10th district of Paris. It was probably followed by a ceremony in a synagogue, but we have no record of this. The guests included the couple’s parents, together with David’s brother, a trader, and his sister, who was not working at the time.

Renée’s brother, Benjamin Storoge, who was a student at the time, and one of her brothers-in-law, a furniture dealer, were also at the ceremony. The couple moved in with David’s parents at 52 rue des Vinaigriers. The marriage certificate lists David as a sales clerk and Renée as a saleswoman.

II) Simone (also known as “Moumoune”): birth and childhood

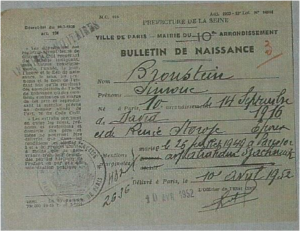

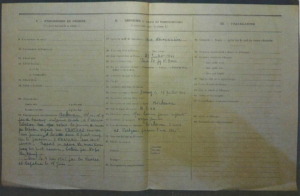

On September 14, 1916, at 6:00 p.m., Renée gave birth to our very own Simone Bronstein, who her family fondly called “Moumoune”. (Jacqueline Storoge, a daughter-in-law of Maurice Storoge, the eldest son of Renée’s family, explained this a handwritten letter.)

Simone Bronstein’s birth certificate

Source: French National Archives Paris (online)

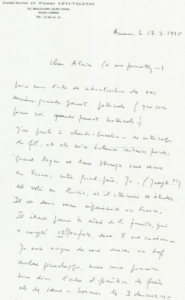

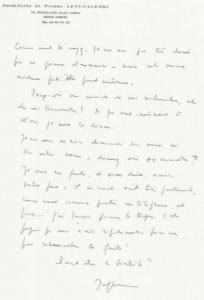

Letter written by Jacqueline Levi-Valensi, the daughter of Marguerite Storoge (Simone’s aunt), whose parents and brother were deported to and died in Auschwitz in 1942. Her uncle, Victor Storage, kept her hidden during the war. After the war, her other uncle, Charles, who had no children of his own, then adopted her.

Jacqueline Levi-Valensi PhD, an associate professor of Classics, was a leading figure in the study of the French philosopher and author, Albert Camus.

Dear Alain (if I may call you that..)

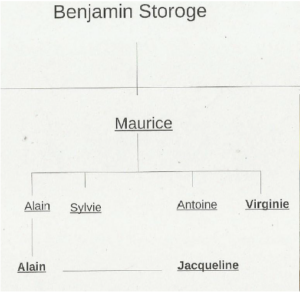

Here is the naturalization certificate for your great-grandparents ( my maternal grandparents). I spoke to Claude Gosselin about our phone call and she cleared up a few details for me. When Grand Meyer and Marie Storoge came to France, your grandfather (Joseph?) stayed behind in Russia to finish his education. He therefore came to France separately. He was among the eldest children in a family of 12, 8 of whom survived. I’ll try to draw up a brief family tree for you, but I can’t tell you the order in which the brothers and sisters were born, apart from the last 3.

As you can see, I’m not very good at this sort of thing, but maybe it will help us all the same. Do keep me up to date with your research and what you find out! If I ever get to Kiev myself, I’ll let you know. I haven’t asked about you or your sister: tell me your news? In fact, to be honest…

Although your father wrote to me, and we spoke on the phone, and then, well… I let the time slip by. This is why I’m writing to you so quickly, to reconnect with the family! Hear from you soon, perhaps?

Victor, the doctor, born in 1900 in Kremenets (due to a return to Russia)

Marguerite, my mother, born in 1903 in Paris

Charles, born in 1907 in Paris.

On the family tree, starting from Rénée (Simone’s mother) she wrote:

Daniel Bronstein 1 daughter Simone known as Moumoune. All 3 were deported. Moumoune came back, married, no children = Mr Gachot 13 rue de Trévise 75009 Paris (she must be nearly 80, her husband a little older…) According to Claude, she is the only daughter who would be able to give me any details about the family. Claude saw her a short while ago, and was impressed by her memory… She is, I believe, very keen to renew a long lost connection (even with me, I admit among the family).

Simone was born at 65 rue du Faubourg Saint-Denis in the 10th district, since her parents had moved by then. In those days, children were born at home.

Where Simone was born and raised

Simone was the couple’s only daughter, and as she was born in France, she was obviously entitled to French citizenship according to the “droit du sol” (being born in the country) legislation.

III) Simone’s life before the German occupation in 1940

1. Where she lived

The doorway of 65 rue du Faubourg Saint-Denis (front elevation)

Behind the entrance doors

At the end of the pathway, the burgundy-colored buildings were most likely workshops.

Recent photo of the pathway.

Simone may well have fetched water from this fountain in one of the lanes

2. Her education

Simone Bronstein almost certainly went to the local elementary school, which was at 34 rue Faubourg Saint-Denis in the 10th district of Paris, but unfortunately, we are unable to confirm this. The school’s current principal, Claire Legentil, together with some of her students, kindly agreed to help us.

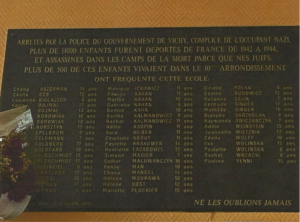

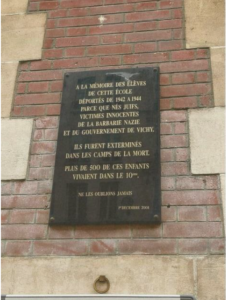

However, as Simone would have been at the school between 1922 and 1927, her name is not listed in any of the registers. Mme Legentil’s students therefore sent us some photos of the school and the commemorative plaque listing the names of all the Jewish children who were deported in the days of the Vichy regime.

Photo of the elementary school at 34 rue du Faubourg Saint-Denis

Deportation commemorative plaque with all the names of the Jewish children from the school who were deported. It was a girls’ school, hence they are all girls’ names.

Another commemorative plaque on the exterior wall of the school.

3. Simone’s uncle Victor’s wedding

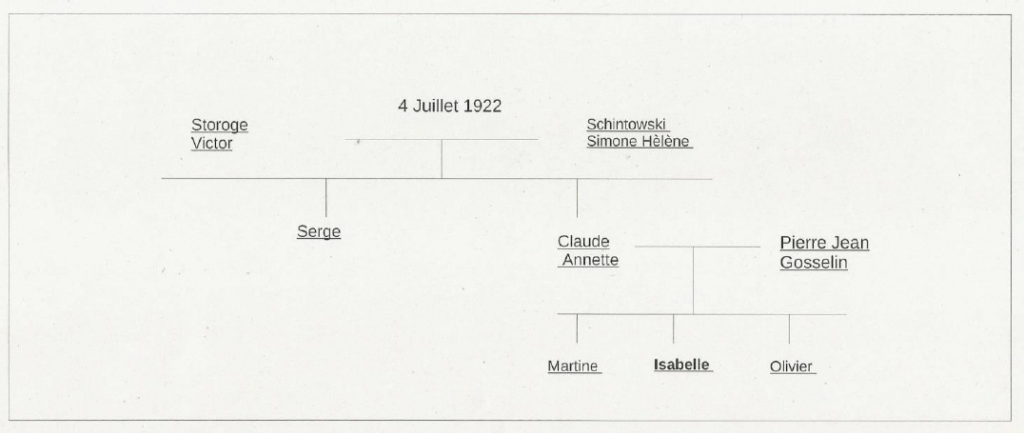

Her uncle Victor (Renée’s brother) married Simone Schintowski on July 4, 1922. He was a doctor, while she was a teacher.

Photo of Victor Storoge, Simone’s uncle

Benjamin Storoge, who was the eldest of the family, was a witness at the wedding.

Virginie Storoge (Simone’s second cousin)

The couple went on to have two children: Serge, who was born in 1927 followed by Claude Annette in 1930. We can only imagine how happy Simone, as an only child, was to have these two cousins.

Simone’s uncle Victor Storoge’s family tree

Photo of Isabelle Moreshi Gosselin

4. Life in Faubourg Saint-Denis

In the 1920s and ’30s, Faubourg Saint-Denis was renowned for its cinemas, cafés and stores. According to our research, it was bustling street with a blend of industrial sites, craft workshops and retailers. The entertainment industry, textiles, hides and skins and music paper manufacturers stood side by side with wholesalers. Tailors, cutters, furriers, penmakers, embroiderers and lingerie makers, as well as typographers, lithographers and cinema ushers, were among the Faubourg residents’ occupations.

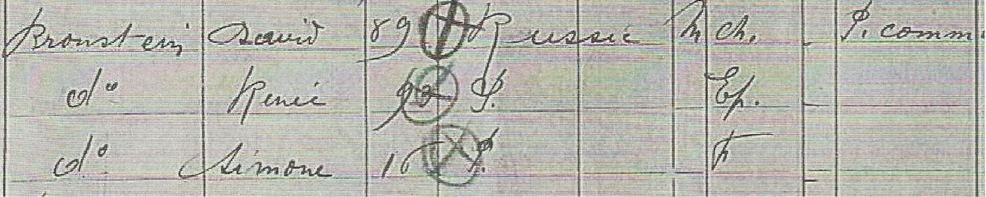

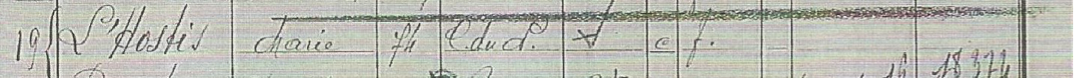

David had a small business, which suited the neighborhood perfectly. According to the 1926 census, David was a storekeeper and then, according to the 1931 census, he became a paper merchant and by 1936, he had become an envelope merchant. We can safely assume that Simone and her mother helped him with his work.

Source: 1926 census: French National Archives, Paris.

Source: 1931 census: French National Archives, Paris.

Source: 1936 census: French National Archives, Paris

Here again, census data enables us to analyze the geographic background of the local population. Few of them were native Parisians. Many came from elsewhere in France (the Cantal, Nord, Loiret and Haute-Saône departments for example) or from foreign countries (Poland, Russia, etc.).

After the First World War, France was short of manpower. At the same time, it was a safe haven for people fleeing revolutions, pogroms and mounting fascism in Europe.

The Great Depression, which began in 1929, and the rise of the extreme right-wing groups then turned foreign workers into a so-called “undesirable” workforce.

On January 30, 1933, Adolf Hitler was elected Chancellor of Germany. Few people had yet read his book “Mein Kampf”, in which he clearly expressed his anti- Semitic views, but it heralded the disaster that was to follow.

Did Simone keep abreast of international events and sense the danger that lay ahead? She was only 17 at the time.

In February 1934, just a stone’s throw from Faubourg Saint-Denis, marches were held by various groups threatening to end the French Republic and overthrow Parliament. Anti-Semitism was on the rise again in France.

Simone and her parents must have seen and heard the threats…but what could they do? Could anyone have imagined what was about to happen?

IV) Simone and her family during the German Occupation

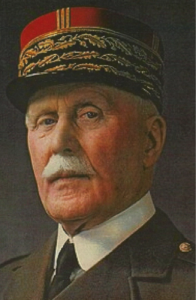

Over the six weeks between May 10, 1940 and June 22, 1940, the German army occupied the whole of northern France. Marshal Pétain, who was widely regarded as the savior of the battle of Verdun, was appointed to lead the country and put an end to hostilities.

Portrait of Maréchal Pétain

Source: French History-Geography textbook, published by Hatier.

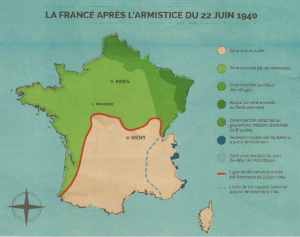

The armistice was signed on June 22, 1940. Marshal Pétain was put in charge of the government and promptly began to crack down on the Jews.

Map of Occupied France after the armistice

Source: French History-Geography textbook, published by Hatier

Jews had to register themselves in a special census and as of September 27, 1940, if they were engaged in a commercial activity, they had to display a sign saying “Jewish business”.

Did Simone and her family go to register? Did David put a sign up on his little store? According to the records, he did not, and was promptly arrested as a result.

In October 1940, following a meeting between Pétain and Hitler at Montoire, the Vichy regime began to collaborate with the Germans.

Later in October 1940, the first decree on the status of Jews was enacted. “Any person born of three grandparents of the Jewish race, or of two grandparents of the said race if their spouse is Jewish, is deemed to be a Jew”.

This first decree gave the Prefects of French departments the power to intern “foreigners of the Jewish race” in “special camps”. David Bronstein, Simone’s father, was therefore at risk. The decree also barred Jews from working in the civil service, the army, education and journalism.

The front page of “Le Matin” newspaper of October 19, 1940

Source: Hérodote.net

In March 1941, Xavier Vallat was appointed head of the newly-founded Commissariat aux Questions Juives (Commission for Jewish Affairs), which was responsible for overseeing the “Aryanization” of French businesses. This paved the way for Jewish assets to be confiscated, a task facilitated by often-greedy interim managers.

A second decree was enacted in July 1941, making it compulsory for Jewish businesses to be registered, and barring Jews from all commercial and industrial activities.

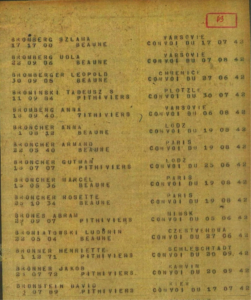

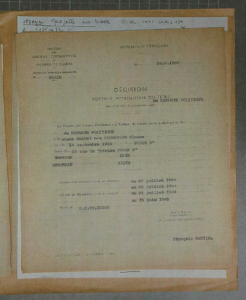

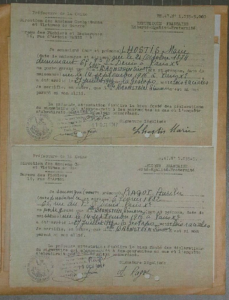

The Paris police arrested Simone’s father on November 17, 1941. He was then sentenced to three months in jail for continuing to operate a business that Jews were no longer allowed to undertake.

Source: Spoilation record (Ministry of the Interior, Commission for Jewish Affairs)

An interim manager was then nominated to wind up the business.

The spoliation report states that David Bronstein’s business was “Buying and selling printed stationery and envelopes”, that it was founded in 1915 and that the address was 65 rue du Faubourg Saint-Denis, which was also his home address.

Source: Spoilation record (Ministry of the Interior, Commission for Jewish Affairs)

A man called René Cornu, a stationery salesman, who had won the French War Cross and was, most importantly, “Aryan”, bought the company for 8,000 francs. He had to declare on his honor that he, his parents and his grandparents were all Aryan.

Source: Spoilation record (Ministry of the Interior, Commission for Jewish Affairs)

The report also notes that Mrs. Bronstein (Simone’s mother) was aware of a few invoices still outstanding after the business ceased trading, and wanted to cover the shortfall out of her own pocket rather than leave behind any debts.

Source: Spoilation record (Ministry of the Interior, Commission for Jewish Affairs)

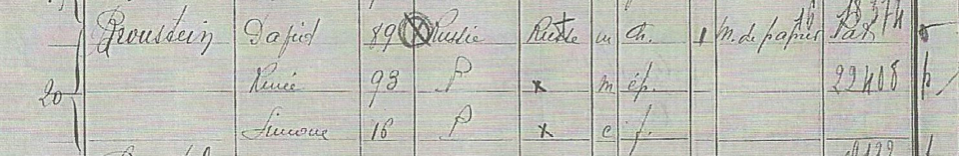

David had failed to declare his business as Jewish-owned. As he had not complied with the law, he was arrested and locked up in Tourelles on November 17, 1941. This former military barracks used to hold “undesirable foreigners” (Jews, refugees, stateless persons, etc.). He was released on January 26, 1941.

Photo of the Tourelles barracks (20th district of Paris)

Source: Wikipedia

According to the Shoah Memorial archives, he was arrested again and sent to the Pithiviers camp, in the Loiret department of France, on February 11, 1942.

Map showing the location of the Pithiviers camp

Source: Arolsen Archives, in the German town of Bad Arolsen

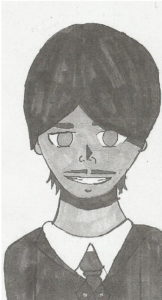

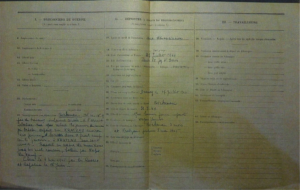

When he arrived at the camp, his physical description was documented. The form reveals that he had blue eyes, greying chestnut hair, a medium-sized forehead, a straight nose, a long face and an American-style moustache. He was 5’7” tall.

He was wearing a grey striped overcoat, grey pants, a Basque style beret and black lace-up shoes.

Source: Pithiviers / Beaune La Rolande camp records

Maddy’s drawing of Simone’s father

David was held in the Pithiviers camp from February 11, 1942 to July 17, 1942. The camp covered an area of around 12 acres, was surrounded by barbed wire and overseen by over 100 military policemen. Between 90 and 200 men were housed in each 2000 square foot barrack hut. The wooden barracks had tin roofs, which meant that they were very cold in winter and hot in summer. The internees worked in various factories in Pithiviers (sugar mills, malting plants etc.) and on nearby farms, or in some case further afield, in the Sologne region for example. Some internees managed to escape, but David was not one of them.

Families occasionally visited the internees, but we have no way of knowing whether David, Renée and Simone were lucky enough to spend a day or two together in this way. Simone was 26 by then. No longer a child, she must have been a great support her mother.

Photo taken from Serge Klarsfeld’s book “1941, Les Juifs en France, prélude à la Solution finale” (1941, The Jews in France, prelude to the Final Solution)

Source: Shoah Memorial / Ministry of Foreign Affairs collection, ref. CILL_189

Internees standing outside the barracks on the southern part of the Pithiviers internment camp on November 27, 1941. Source: Shoah Memorial, ref. CILL_414

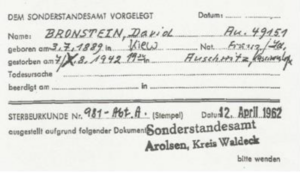

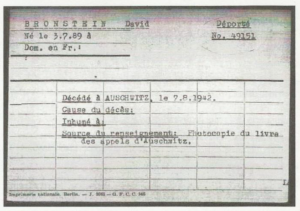

At 6:15 am on July 17, 1942, David Bronstein was deported from Pithiviers station on Convoy 6, bound for Auschwitz-Birkenau. This date bears a certain significance. The aim was to make room in the camp for the families arrested during the Vélodrome d’Hiver roundup, which took place in Paris on July 16-17, 1942. 928 Jews, including both adults and children, were deported on Convoy 6, the first of the convoys to carry that many women and children. The journey to Auschwitz took 3 days and 3 nights. Some people died on the way, mainly from exhaustion or suffocation. David, although he was probably unaware of it, was in the same car as a Russian novelist by the name of Irène Némirovsky, who, like him, was born in Kiev in 1903. According to the Arolsen archives in Germany, when David arrived in Auschwitz, he was assigned prisoner number 49151. He died there on August 7, 1942.

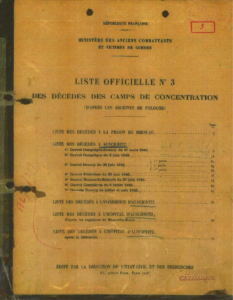

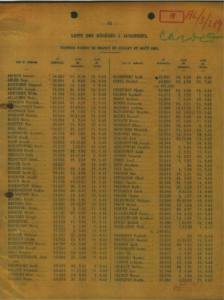

Source: French Ministry of Veterans’ Affairs and Victims of War archives.

Source: Arolsen Archives, in the German town of Bad Arolsen

Source: Arolsen Archives, in the German town of Bad Arolsen

Source: Arolsen Archives, in the German town of Bad Arolsen

Meanwhile, Simone’s uncle Victor was still living in Paris. His children did not wear the yellow star. Victor and his family decided to move out of Paris and take Jacqueline, who had lost her parents and brother, with them. But why didn’t Simone and her mother go with them? Perhaps they felt they should be there in case David was released and came home.

Photo of Serge and Claude-Annette (Simone’s uncle Victor’s children) taken in front of their house in Paris in April 1942.

Jacqueline, Claude Annette and Serge after April 1942

According to Isabelle, Claude-Annette’s daughter, the family took refuge in several different places including Nevers, Clermont-Ferrand, Perpignan in the Niévre, Puy-de-Dôme and Pyrénées-Orientales departments of France respectively. While they were in Perpignan, Serge was reported and very nearly arrested at his high school. The family then moved closer to the Spanish border before returning to the north of France, where Serge and his father, Victor, joined the Resistance.

Photo of Serge, his father and some other Resistance colleagues.

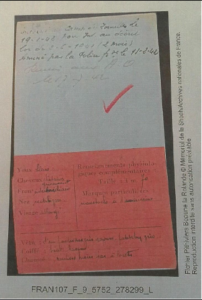

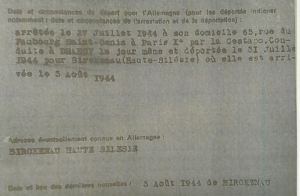

On July 27, 1944, after the someone reported them, the Germans arrested Simone and her mother at 65 rue du Faubourg Saint-Denis in Paris.

Source: French Ministry of Veterans’ Affairs and Victims of War archives

Had they been living in hiding until then? Did they wear the Jewish star? Did they stop wearing it when Simone’s father was arrested? Simone and Renée were taken to the Drancy transit and internment camp. SS commander Aloïs Brunner had been in charge of the camp since June 18, 1943.

Photo of Aloïs Brunner

Source: France Info (AFP archives)

From the moment Aloïs Brunner took charge of the camp, he focused on pushing ahead with the Final Solution. Terror reigned supreme in Drancy. His objective was to hunt down all the remaining Jews in France. He embodied the very essence of extreme anti-Semitism. Hitler had escaped an assassination attempt just three days earlier, and this spurred him on to increase the numbers of Jews arrested. We wonder if this is why the two women were captured so soon afterwards.

Drancy is located to the northeast of Paris, in the Seine-Saint-Denis department.

Simone and Renée arrived in the courtyard in the center of the camp.

Photo of the courtyard at Drancy

Source: Multimedia Encyclopedia of the Holocaust

They were each assigned a serial number, Renée 26029 and Simone 26030. Simone was placed on staircase 18, in a room on the 3rd floor. We suppose that her mother was as well.

Living conditions in Drancy were very tough. It was an internment camp, in which prisoners slept on the floor, crammed together on the concrete. The buildings had no heating or other facilities. Showers were in a barrack hut at the far end of the courtyard. Laundry was done outside in a type of concrete trough, as can be seen in this picture. Diphtheria (a respiratory infection that causes damage to the central nervous system, throat or other organs, leading to death by asphyxia/disease) swept through the camp.

Photo of women doing their laundry.

Source: Larousse Encyclopedia

Simone and her mother Renée only spent four days in Drancy camp. Were they forced to work? Were they beaten? We do not know. What we do know, however, is that Aloïs Brunner organized the deportations by sorting people into three groups: A (Aryans, spouses of Aryans and half-Jews), B (Jews), who were to be deported as a matter of priority, and C (those who were on hold for some reason). As Simone and Renée came into the B category, they could not remain in the camp for long.

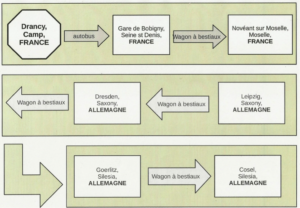

Simone and her mother left Drancy and were deported from Bobigny station to Auschwitz on July 31, 1944, just eighteen days before the camp was liberated. Convoy 77, with 1309 people on board, including 324 children, was the last convoy to leave Drancy.

Camp locations

On the crowded platform at Bobigny station, Simone must have been totally bewildered: she would have been expecting a passenger car with heaters and comfy seats, but instead there stood a cattle car. She must then have realized that she and all the other deportees were about to spend an unforeseeable length of time in a mere cattle car. They were to be treated like animals. This is yet another example of the humiliation that Adolf Hitler’s Nazi regime inflicted on the Jews. Simone, her mother and all the other deportees were herded into the cattle cars as quickly as possible, no doubt amid shouts by Alois Brunner’s sadistic SS guards. Were Simone and her mother insulted, or hit, or pushed to force them to get on the train? She was 28 at the time, and her mother 51. Just picture the scene: there were no steps to climb aboard, so people had to haul themselves up with their arms. Simone probably found it easier to get on than her mother. Perhaps she helped her up? From that point on, they were all crammed in together in what were sometimes called “the death cars”.

Photograph of a cattle car like those in which people were deported to the camps.

Source: 447 Holocaust Train stock photos

The travelling conditions in the cattle cars were abominable. Each car was packed to the limit, meaning that some prisoners had to stand up. Most of the cars were almost entirely closed, leaving the deportees in the dark. There was only one bucket in the middle for people to relieve themselves. One can only imagine how humiliating it was to have to do this in front of strangers, as well as the stench it caused even after a few hours. The journey lasted three days and three nights.

The towns and cities that Convoy 77 passed through

Tracé des étapes empruntées par le convoi 77

Source : Mémorial de la Shoah

Simone and her mother no doubt arrived at Auschwitz exhausted but perhaps also somewhat relieved. It was August 3, 1944. When the doors swung open, the deportees must have felt a rush of freedom as a blast of fresh air filled the cattle car. Were some of them already dead? What must Simone and her mother have been thinking? Were they going to have to work? It would be hard, for sure, but would they manage it? How could they possibly have imagined that they had arrived in a concentration and extermination camp, and that their lives were hanging by a thread?

Maddy’s drawing “Simone arriving in Auschwitz”

The “selection” was carried out as soon as they got off the train. Simone, who was 28, could still be useful as a worker. But what about her mother? We have no records of her physical appearance, but a woman of 51 in 1944 would have looked older than someone of that age today. According to the archives, a missing person’s report for Renée was drawn up, saying that disappeared on August 5, 1944. This official record gives the reason for her having been deported as “racial policy”. After August 4, Simone was forever separated from her mother.

Renée Bronstein’s death certificate.

Source: French Ministry of Veterans’ Affairs and Victims of War archives.

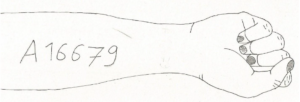

Simone, then, was selected to go into the camp to work, together with another 183 women on the convoy. After the “selection process” came humiliation and nudity. The deportees had to get undressed in public and were then shaved and had a number tattooed on their forearm. They were treated like cattle. Simone’s number was A16679. She no longer had a name; now she was nothing more than a number.

Noémie’s drawing

The deportees also had to put on “striped pajamas” or other old clothes and shoes that did not fit.

Photo of a deportee’s uniform

Source: Museum of the Resistance and Deportation (France)

Simone would then have been sent to her barrack hut. The barracks were in blocks of two, built out of wood. The walls of the space were lined with bunks made of wooden planks. The women slept huddled together to keep warm. It was very cold in winter and extremely hot in summer. This is where Simone slept, alongside her fellow prisoners. At that point, would she have even known what had become of her mother?

Photo of the inside of a barrack hut

Source: Pédagogique.ac-nantes.fr website

Every day in Auschwitz began with the roll call. The SS commandos called out the women’s names one by one. Simone had to go through this long, drawn-out process, standing up for hours on end. The roll call often involved public humiliation and punishment, such as having to squat for a whole hour.

Photo of the roll call yard

Source: French website Fortitude-WW2, History of the Second World War WW2

Auschwitz-Birkenau was both a concentration camp and an extermination camp. Selections were sometimes carried out in order to make space in the camp. Simone may have experienced some of these. In any event, she must have realized very early on that her mother had been selected for extermination. The women who had been in the camp the longest did not necessarily take the time to explain the unspeakable. As Ginette Kolinka (another Auschwitz survivor) so aptly put it, “the women showed me the chimneys in the distance. At first, I didn’t understand, but soon afterwards, when I saw the smoke and smelled the odor, I understood what had happened to my father, who was also deemed to have been too old and weak to work”.

Photo of the chimneys at Auschwitz

Source: La Une Courrier Picard

Photo of the crematorium ovens at Auschwitz

Source: Photoway.com. Richard Soberka

After the roll call, Simone, together with all the other women, had to work. Working conditions in Auschwitz Birkenau were appalling. The SS officers in charge had no qualms about beating and humiliating the women. According to historical records, there was a saying “no work but chores”. Was this better? Easier? Were they more likely to come out of it alive? Simone somehow managed to survive this hell. She spent two months in the Auschwitz extermination camp. She and around 300 other women were then transferred to a concentration camp. From then on, she did not have to endure any more “selections”.

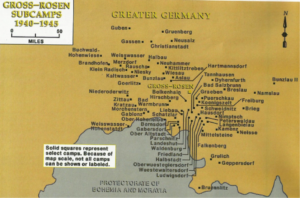

After a journey that lasted several days, presumably in cattle cars once again, Simone arrived in the women-only Kratzau camp, which was annexed to the Gross Rosen camp.

Map showing the location of the Gross-Rosen annex camps, including Kratzau

Source: Holocaust Encyclopedia

She stayed there from October 1944 to May 1945. The camp was a women-only ammunition manufacturing camp. The women had little to eat and were often beaten by the camp kapos.

Source: French Ministry of Veterans’ Affairs and Victims of War archives

The days were in Kratzau were all much the same: “Between 3:30 and 4:20 in the morning, the deportees had to stay in the dormitories, but were able to take hot showers. After the roll call, the deportees went to fetch their watery soup, which was sometimes thickened with a few raw potato peelings. At the same time, the deportees were given their daily ration of bread, around 8 ounces with less than an ounce margarine, a slice of sausage or a spoonful of jam. At around 5am, the day shift left for the factory near the camp. They worked from 5am to 6pm. When they got back to the camp, the women waited in the courtyard for their evening meal. This consisted of about two pints of soup. At around 9:00 pm, the women had to go back to their dormitories, and then it was curfew time.” (United States Holocaust Memorial Museum). The “Spreework” factory was built to manufacture ammunition and grenades, as well as various weapons that were sent to the Reich and thus destined for the Wehrmacht.

Five-sided badge issued to Helen Waterford identifying her as a prisoner from the Kratzau-Chrastava labor camp, a satellite camp of Gross Rosen.

Source: United States Holocaust Memorial Museum

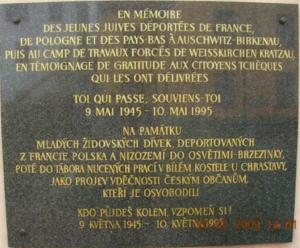

A commemorative plaque in Chrastava (a town in the Czech Republic)

2 500 women worked in the factory at Kratzau. We think there were more than that but the factory could not employ them all due to a shortage of machinery and raw materials such as fuel oil.

On May 7, 1945, Simone and the other women all had to gather together. Neither the day nor the night shift went to the factory. The factory manager then announced that the war was almost over, and wished them a safe return to their homeland.

On the morning of May 9, 1945, the women woke up to find the camp deserted. They SS officers had all gone, leaving their uniforms behind. It was the Soviet army that liberated the camp.

Map of the liberation of Europe.

Source: French Education Institute.

According to the records, Simone was initially taken to the town of Pilsen in what is now the Czech Republic. From there, she was flown back to the Lyon-Bron airport in France on June 15, 1945.

Source: French Ministry of Veterans’ Affairs and Victims of War archives

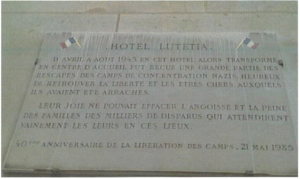

How did she get from there to Paris? Did she go to the Hotel Lutetia, which General de Gaulle had requisitioned to take in returning deportees? Did she manage to find her uncle right away? Did he bring a photo to the hotel in the hope of finding his niece? Was he searching for his sister Renée too? We found no answers to these questions.

Plaque on the wall of the Hôtel Lutetia in Paris

Source: Cercle d’étude de la déportation et de la Shoah (Study group on deportation and the Holocaust)

V) Simone’s life after the war

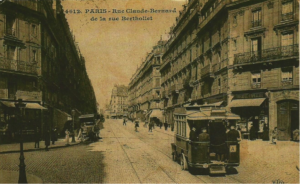

Simone, who had lost both her mother and father, went to live with her uncle Victor and his family. Her uncle, in fact, had lost no family members. He lived at 77 rue Claude Bernard in the 5th district of Paris with his wife Simone and their children, Serge, who was 18 at the time, and Claude-Annette, who was 16.

Postcard showing the rue Claude Bernard in the early 20th century

Source: Cartorum

Source: French Ministry of Veterans’ Affairs and Victims of War archives

As he was a medical doctor, we assume that Victor helped his niece to begin eating properly again and to try to return to some semblance of a “normal life”. Was she able to talk about what she had been through? According to a handwritten letter that Jacqueline, (one of Simone’s relatives) sent us, Simone did eventually open up to Claude-Annette (her uncle Victor’s daughter), but only much later on.

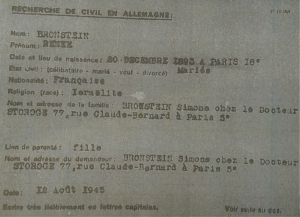

On August 12, 1945, Simone requested a “civilian search” in Germany for her mother, whom she had not heard from since they had arrived in Birkenau the previous August.

Source: Arolsen Archives, in the German town of Bad Arolsen

After a while, Simone met Abraham Szachniuck, who was born on March 19, 1905 in Luck, Poland. His parents were Mojsze Chaïm Szachniuck and Zlata Rejzla. We tried to put together Abraham’s family tree but unfortunately our inquiries in Poland came to nothing.

Photo of Mara Szachniuk, a relative of Abraham

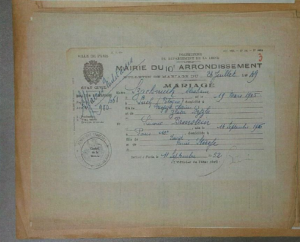

They were married on July 26, 1949 in the 10th district of Paris. Simone was 33 by then, and Abraham was 40.

Photocopy of Simone and Abraham’s marriage long-form certificate

Simone and Abraham’s marriage certificate

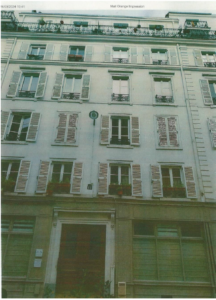

Did they also have a religious wedding in a synagogue? Our requests for information from the synagogues in the 10th district did not produce any results. On the marriage certificate, Abraham is listed as an accountant and Simone as a storekeeper. Might she have followed in her parents’ footsteps? After they were married, the couple set up home together at 13 rue de Trévise in the 9th district of Paris.

Photo of 13 Rue de Trévise

Simone and Abraham lived in the 9th (IX) district of Paris

In 1953, Abraham changed his surname by court order. From then on, the couple were no longer called Szachniuck, but Gachot. We thought long and hard about this name change. It might have been because the name was too awkward to use, to avoid a family name dying out, because they felt it was disadvantageous, or simply because they wanted to “Frenchify” it… We went for the last option, but after doing a bit of research, we realized that he did not choose the name at random. In fact, Abraham’s witness at the wedding was Rachel Gachot, a medical doctor who live in Orléans, in the Loiret department of France. Did this woman, who was 42 at the time of the wedding, help the family in some way during the war? Given that she was a doctor, did she know Victor Storoge, who was also a physician? Did she play some role in Abraham’s life, perhaps in that of his family? Either way, Abraham’s wish to become “more French” became evident again in 1978, when he changed his first name to Albert.

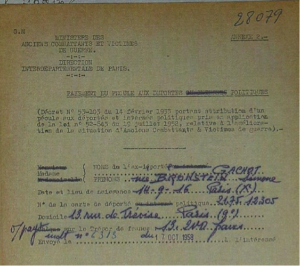

On May 23, 1958, Simone was granted the status of political deportee, meaning that she had been deported on political grounds. She had officially applied for this beforehand. Her card number was 21.75.12305. As a result, she received a compensation payment of 13,200 francs.

Source: French Ministry of Veterans’ Affairs and Victims of War archives

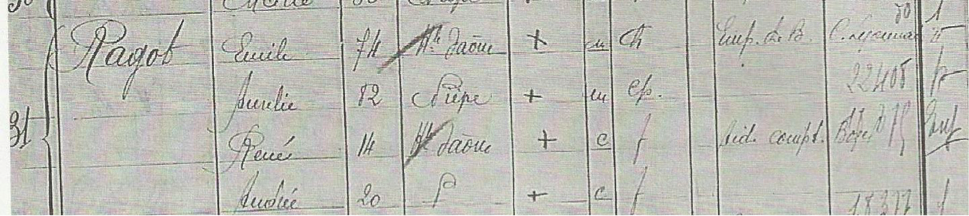

Two witnesses had to confirm that they had seen the arrest take place. Marie Lhotis and Aurélie Ragot, two neighbors who lived at 65 rue du Faubourg Saint-Denis, testified to having been there when Simone and her mother were arrested.

Source: 1931 census: French National Archives, Paris (online)

Source: French Ministry of Veterans’ Affairs and Victims of War archives

Source: French Ministry of Veterans’ Affairs and Victims of War archives

Source: French Ministry of Veterans’ Affairs and Victims of War archives

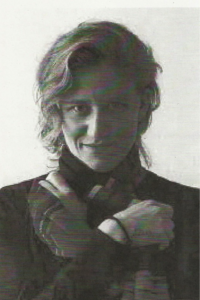

What was life like for Simone after the war? Isabelle, her uncle Victor’s granddaughter, found this photograph for us. It was taken at a family gathering, but it is hard to say how old Simone was at the time.

Simone Storoge, Claude Annette Storoge and Simone Bronstein

Source: Family photo found by Isabelle (Victor’s granddaughter)

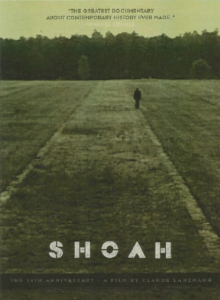

What about her later years? We really do not know. When people in France and around the world began to discuss the Holocaust, did Simone and Abraham want to listen? Did they want to share their stories? Did they follow the trial of Adolf Eichmann, who was responsible for deporting and murdering thousands of Hungarian Jews? Did they go to see Claude Lanzmann’s movie “Shoah”?

Photo of the Eichmann trial.

The poster for the movie “Shoah”

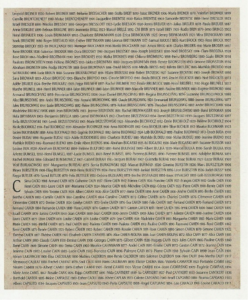

We do know, however, that Simone never got to see her name or those of her parents on the Wall of Names at the Shoah Memorial in Paris, which was inaugurated in January 2005.

Source: The Wall of Names at the Shoah Memorial in Paris.

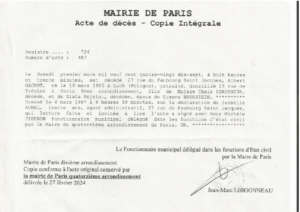

Albert (Abraham) died on March 1,1997 at 27 rue du Faubourg Saint-Jacques, which is the Cochin hospital in Paris.

Simone died on August 11, 1997 in Menton, in the Alps-Maritimes department of France, just six months after her husband.

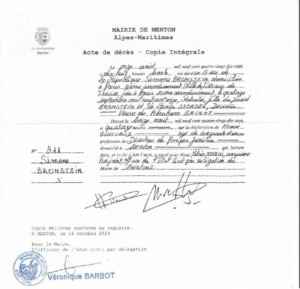

Death certificate (long version)

At some point in their lives, Simone and Abraham bought an apartment at 15 rue de la République in Menton which was where she died. Her body was later brought back to Paris for burial.

The apartment building in Menton, at 15 rue de la République.

They are both buried in the “Jewish plot” in the Montparnasse cemetery in Paris.

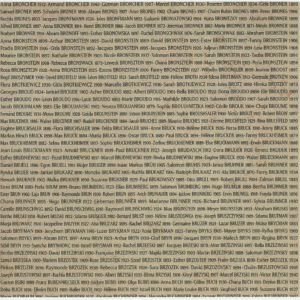

They arranged to have the following inscription on their grave as a final tribute to their parents: “In memory of our parents, Mojsze Szachniuck Zlata Szachniuck David Bronstein Renée Bronstein, who died during the Shoah”.

This verse from the Bible (probably at Simone’s request, since she died last) is also engraved on the tombstone: “Though the mountains be shaken and the hills be removed, yet my unfailing love for you will not be shaken nor my covenant of peace be removed” Isaiah 54:10.

This, together with the star at the top, suggests that the couple remained religious.

Photo of Simone and Abraham’s tomb in the Jewish section of the Montparnasse cemetery.

SOURCES

- French National Archives in Paris

- Ministry of the Armed Forces: Archives of Victims of Contemporary Conflicts Division

- Shoah Memorial

- Paris Police Headquarters Archives

- Yad Vashem Memorial Archives, Jerusalem

- Bad Arolsen Archives

- Archives-loiret.fr

- Convoy 6 memorial association

- Central Historical Archives of the State of Ukraine

- Union of Auschwitz Deportees

- United States Holocaust Memorial Museum

- Museum of Jewish Art and History

- Paris City Hall (10th, 9th districts)

- Menton Town Hall: Véronique Barbot

- 34 rue du Faubourg Saint-Denis elementary school; Claire Legentil, the principal, and her students

- Our conversations with family members: Jacqueline Storoge, Isabelle Gosselin, Virginie

- Storoge and Mara Szachnuik

- Our discussions with two historians: Alexandre Doulut and Sandrine Labeau

- Our discussions with our Convoy 77 contacts: Serge Jacubert and Claire Podetti

STUDENTS’ COMMENTS

Romane

“The Convoy 77 project was a really, really good discovery for me. It was a truly rewarding project that helped me become more independent. There was a super atmosphere all year long. I loved it!”

Eudoxie

“Convoy 77 was an incredible eye-opener. It enabled us to become more independent and to help the historians to complete their research in an enthusiastic atmosphere.”

Paul

“The Convoy 77 project was an enlightening experience every hour I spent on it. I would recommend it.”

Jeanne

“Convoy 77 was an inspirational experience. Contacting, calling and writing to new people in other countries was super interesting. I really enjoyed it. Thank you.”

Dimitri

“I loved working on this project: we made history by working in a different way. It helped me learn a number of things. The group atmosphere was great. Thank you for giving us the opportunity to work on this project.”

Louis

“The Convoy 77 project was an enlightening experience. We were able to learn more about the persecution of Jews in France. It was a different kind of history. We got to play detective, send e-mails, make phone calls. All this to write the biography of a deported person and produce an exhibition at the end.”

Joseph

“I really enjoyed the Convoy 77 project, which taught us a lot about history. I enjoyed working as a team with the other students. We all had a part to play and we were all involved in retracing Simone’s life.”

Honorine

“The convoy project taught me more about the history of the Holocaust. I found the project very rewarding. I discovered a small aspect of what historians do.”

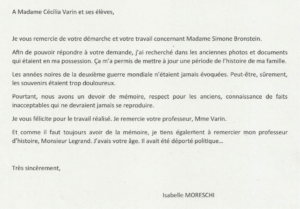

LETTERS FROM FRENCH AND INTERNATIONAL ORGANIZATIONS THANKING THE STUDENTS WHO TOOK PART IN THE CONVOY 77 PROJECT

THANK YOU MESSAGES FROM THE FAMILY

SOME OF THE EXHIBITION BOARDS

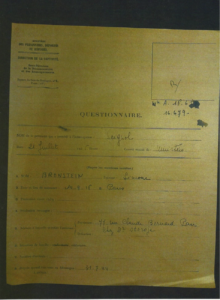

Questionnaire on the Simone Bronstein exhibition (open to all school grades)

HER FAMILY

- What were Simone’s paternal grandparents’ names?

- What were Simone’s parents’ names?

- Where was her father born?

- What was his nationality?

- Where was her mother born?

- What was her nationality?

- Where was Simone born?

- When was Simone born?

- What was her nationality?

- What was the family’s religion?

SIMONE AND HER FAMILY’S LIFE DURING THE GERMAN OCCUPATION

- Who came to power in Germany in 1933?

- Between May 1940 and June 1940, who invaded our country?

- Who was appointed to lead France?

- What attitude did this man adopt towards Germany?

- What measures were taken in France against the Jews?

- What should Simone’s father have done? When he failed to do it, he was arrested.

- Where was he initially sent?

- What was the name of the internment camp to which he was sent after his imprisonment?

- Which camp was he sent to next?

- On which convoy?

- When did he die?

- How were Simone and her mother arrested?

- To which internment or transit camp were they sent?

- On which convoy were they deported from France?

- Where were they taken?

- What happened to Simone’s mother?

- Why did this happen?

- Where was Simone sent next?

- What did she do there?

SA LIBERATION ET SON RETOUR

- When was she liberated?

- By whom?

- When she came back, who took her in?

- When did she get married and to whom?

- Where is their grave?

- Who does the inscription on the grave pay tribute to, and why?

- Bonus question: how many times is Simone’s first name mentioned in the exhibition?

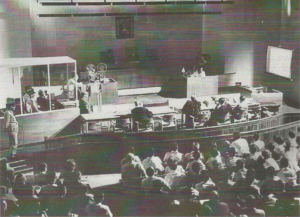

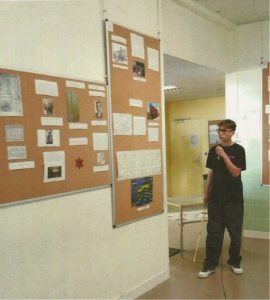

EXHIBITION OPENING, JUNE 27, 2024

The students presented their biography of Simone Bronstein, followed by a testimonial from Virginie Storoge (Simone’s relative), who attended the event via video link.

Source: Article in the newspaper “la Manche”: July 2, 2024.

You can also read our article in French, “Une exposition autour de Simone Bronstein”

Français

Français Polski

Polski