Simone ZUCKERMANN

Left, Simone at age 19, on her return from the camps in 1945 © archives Mémorial de la Shoah/Adeena Horowitz

Simone Zuckermann died on June 10, 2012 at the age of 85. Georgette Zuckermann died in 2022 at nearly 94, too late for us to meet her. To tell the story of Simone’s and her sister Georgette’s lives, we imagined a dialogue between them.

We know Simone’s voice well, since she recorded her testimony over twenty years ago, in English, in the United States, where she lived: we’ve largely used her own words, only translating them into French. As for Georgette, she left us no account of her life: to write her voice, we therefore had to cross-check all the information we had about her and hope to get as close to her as possible.

Their family

Simone and Georgette Zuckerman’s family came from Russia. Their father arrived in France before the First World War, in which he took part by volunteering for the 2nd Foreign Regiment. A corporal, he was awarded the Croix de Guerre 1914-1918.

Nevakh Zuckermann was granted French nationality by the decree of November 14, 1923. At the time, he was living in Courbevoie (Seine, Hauts-de-Seine), and had a son, Villy, born in 1911 to his partner Angeline Yalvcher. This first child died in 1933 in Bitche (Moselle), at the age of 22, while he was serving in the army. It is not certain that the sisters ever met him, or even knew of his existence.

We have very little information on Nevakh’s second companion, Fania Ifliandik, Simone and Georgette’s mother. She too was born in Russia in 1898, 1899 or 1900. According to the documents, she appears as either Russian or Polish. We don’t know when she arrived in France either, but her older sister, Doba, had married in Paris in 1913.

In any case, from 1931 onwards, the Zuckermann family lived at 25 impasse de la Couture d’Auxerre in Gennevilliers (Hauts-de-Seine), where Nevakh worked as a sheet metal worker on car bodywork.

In the late 19th and early 20th centuries, the “zone of residence authorized for Jews” was a peculiarity of the Russian Empire and its anti-Semitism. Georgette’s parents were born there, her father in Minsk, and her mother in the northern province of Wilna, where 12.90% of the population was Jewish. Map of area of residence from the Jewish Encyclopedia, 1905, vol. 10, art. “Russia” © Wikipedia

Childhood

Georgette: Simone, it occurred to me yesterday that I’ve never had such joys as those of my childhood.

Simone: Ah, do you remember the housing estate where we lived in Gennevilliers, our house on that street whose name I’ve forgotten, maybe you do?

Gennevilliers census register, 1931. On these documents, Fania does not appear as Russian, but as Polish.

Georgette: We lived in impasse de la Couture d’Auxerre, if I remember correctly.

Simone: All those buildings built on the fields… We moved into this complex of small gray pavilions, lost in the middle of the countryside, in the style of the time, with their concrete and stone walls, their slate roofs in a triangle. It was a symbol of middle-class success at the time.

Georgette: Of course, I remember it, but it wasn’t that brilliant…

A street in the same district of Gennevilliers when Georgette and Simone lived there – you can see that the houses were very new then. The impasse de la Couture d’Auxerre became rue Jules Vallès. Source : www.gennevilliers-tourisme.com

Simone: It was a village that had become an industrial zone, I know. But there were still farms, growing cabbage, lettuce and carrots.

Georgette: I remember, the farms still had a stable for one or two horses, and a shed for farm equipment and carts.

Simone: And in springtime, remember the rows of frames and glass bells that served as targets for the neighborhood boys.

They laugh.

Georgette: We used to live next to the Zone, and to be honest, we didn’t live in such a beautiful place. I remember that Gennevilliers was nicknamed “Gadouville les eaux grasses” because that’s where the sewage from Paris was emptied. In summer, it didn’t smell very good… But for me, for us, it’s above all the place, the place of our happy days, our carefree hours, our beautiful youth. Do you remember when, in the living room, we tried to steal the newspaper to read it together, even though we weren’t allowed to? The game was well worth the candle, and we never really got scolded. And then, do you still remember those big concrete paths we used to run along with our friends? They were wide, and our parents weren’t afraid we’d get run over by the few cars on the road… Nothing like today!

Simone: We weren’t far from our school. All along the way, we’d meet up with our friends. Later, when we grew up, the high school was much further away.

Photo of the Pasteur school complex where the girls would have spent their schooling, as this would have been the only school complex in Gennevilliers at the time, and the girls lived just 10 minutes from the school. Source : www.gennevilliers-tourisme.com

Simone: And then there were the two sheds adjoining the house, where our father worked with his ten or so workers. I still remember the sound of their tools banging on the sheet metal of cars during the day… This small workshop enabled us to be part of the middle class, and our father’s work as a metalworker enabled us to live quite comfortably… together.

This 1943 aerial photo shows the girls’ house with what would have been their father’s workshop (circled in red) © IGN-Remonter le temps

Georgette: We led a secure life. But we weren’t as wealthy as our pharmacist cousins in Paris, the Ginzburg’s…

Simone: Do you remember our cousins, Josephine, Pierre and Yves?

The photo on the left, dating from the First World War, shows Uncle Jacques with his wife, Deba (Fania Ifliandik’s older sister) and their daughter Joséphine, and must date from 1915 or 1916. On the right, in 1926, with Joséphine, Pierre and Yves (who is the same age as his cousin Simone) © Geneanet.org

Georgette: In our childhood, not so much, we didn’t see them regularly, we were in Gennevilliers and they lived at the other end of Paris, in the 13th arrondissement. Then, of course, when I moved in with our aunt in 1945, I saw them again.

Simone: Yes, but before the war? You know, Uncle Jacques had fought in the First World War with Dad. That’s how they got their nationality. And then he was deported to Auschwitz on the very first convoy.

The two sisters interrupt each other.

Georgette: Anyway, do you remember how lucky we were to be able to go on vacation to the coast with our family?

Simone: Yes, well, it wasn’t a habit either. I can only remember the one time we went to the seaside. We went to the beach together… We walked on the hot sand. It was a privilege in those days, and our parents tried to take advantage of it.

Georgette: It was so beautiful. In general, we never lacked for anything, and certainly not for love. Our life was beautiful… We lived there happily, but all that had to come to an end when I was 10…

Vacation photo of Georgette and Simone’s family. We don’t know where the photo was taken; the two men are their father, Nevakh, in the white shirt, while the other man would be an uncle or cousin. Nor do we know who the two girls in the background are: at first, we thought they were the two Zuckermann sisters, and yet, according to Simone’s daughter, they’re just two strangers. © Horowitz family archive

Simone: And how, Georgette, could I forget that time? Okay, she was beautiful… but for me so empty. It was beautiful, but it had no meaning. I lived without knowing everything, without knowing myself. We lived thinking that some things were just the way they were, and that we didn’t have to worry about them. I knew I wasn’t a Christian, but do we define ourselves by what we’re not? I was living happily but didn’t know why I was here with my parents but far from my origins. Why did they have to speak Russian sometimes when we were French, we had no explanation of where we came from. Why didn’t our parents have the same nationality as us? We were both French, but our mother wasn’t, which is why she went to Auschwitz so early. She was Russian, just like our father, or so I think.

Georgette: Yes, Russian or Polish, we never quite knew. But it’s true that our father was naturalized in 1933…

Simone: Maybe Dad had said something to you before … I don’t know. But the day I found out I was Jewish, in November 1938, I felt liberated. I still wonder why our parents didn’t put me out of my misery sooner. You can’t be happy without knowing who you really are. I lacked the roots I needed to develop and build myself. The discovery of Judaism was even more than that, it was a second birth…

Portraits of Nevakh Zuckermann and Fania Ifliandik © Horowitz family archives

Georgette: Simone, I don’t think like you… Our life was great… Our vacations by the sea… Altogether, with our father. And I think he was always right to distance himself from that Jewishness… He wanted to spare us from what he had experienced, anti-Semitism. Mom and he, back in Russia, had experienced violence and discrimination…

Simone: Yes, even the pogroms. That’s why they emigrated.

Georgette: If we’d never been Jewish, we’d never have gone to Auschwitz, our mother wouldn’t have died… We’d be with our father, he was so kind… I missed him and still do. He always wanted to keep us out of trouble, and he was right. I know that with the Jewish scouts you found a family, that you were together in the resistance, that Judaism was a discovery for you. But I’ll never be able to remember with pleasure the discovery of our Jewish origins, because they took our parents away from us.

Simone: Oh yes, how you loved your father, and how he loved you, the little sister. You were always his favorite. In his eyes you were the best, the last little one. But you’re right, I found another family, even if I never got over the death of our parents. I lost one family, but I gained another. With the Jewish scouts we were together, we distributed leaflets, we helped each other, without preference, without favorites. We helped hide children, got them out of Paris, distributed false papers, because we had the material. Our group was active… but it wasn’t resistance. Together, it’s true that we went through this period, but we weren’t resisting, we were doing things collectively, things that seemed right to us. And I would have thought it right to be treated like you, I would have thought it right to know my origins, I would have thought it right to be able to be Jewish from childhood!

Georgette shakes her head.

Georgette: You’re blaming me for things that aren’t my fault. You’ve always had a strong character, and our father certainly had trouble with that. But I can understand that it wasn’t easy for you, even if I didn’t have the impression that you were suffering from it. In my memory, you were fine… You liked school and your math lessons, and you were quite brilliant. There weren’t many girls doing the “modern” curriculum, and you were able to start studying medicine when you came back from Auschwitz, which isn’t so common… Your childhood wasn’t so horrible!

Simone: My character…

In Paris under the German occupation

Simone: Do you remember the occupation?

Georgette: Yes…all of northern France was occupied when the Germans arrived in Paris.

Simone: On June 14, their flags were on the Eiffel Tower and they marched proudly through Paris. That was a very hard time.

The Nazi flag flies over the Arc de Triomphe, probably on June 14, 1940. Paris appears almost empty. (anonymous photograph © BPK, Berlin, Dist RMN – Grand Palais – image BPK)

Georgette: Eating became more and more complicated.

Simone: Yes, there were endless queues, and you knew that a black market had developed.

Georgette: Yes, and food cards. It reminds me of the home where I was an instructor; they used to forge tickets to eat with stamps given to them by accomplices at the town hall. Especially us Jews had fewer ration coupons, so apart from the black market…

Simone: Yes, the UGIF children’s homes; the infants were in Neuilly, the under-5s in Louveciennes; there were even children trapped under Gestapo control. We had to organize their departure, but without papers it was complicated to transport them to the farm-school.

Georgette: I was there in Louveciennes, I was an instructor, and I was barely fifteen. Some of the children were well over 5 years old, and some were barely younger than me, twelve or thirteen. And do you remember that scout, “topo”?

Simone: Yes, she helped us a lot, she was a social worker.

Georgette: She worked at the Prefecture of Police, announcing roundups so that we could hide the children. She herself took children across the demarcation line, entrusting them to other scouts; she used the cards of other boys of the same age.

Simone: Thanks to her, over 500 children were able to reach London, Spain or North Africa.

They remain silent for a moment.

Georgette: And then there was the obligation to wear the yellow star. June 1942, that terrible moment.

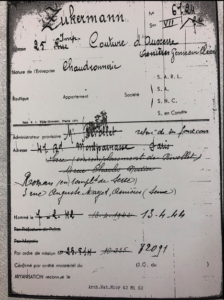

The sisters were subjected to all the anti-Jewish laws. Their father’s business was “aryanized”, and they lost everything (Simone kept the receipt for this confiscation all her life, without ever being able to claim it).

On this document, we can see that there were three successive “administrators” for Nevakh’s business between 1942 and 1944 © Municipal Archives, city of Gennevilliers

Anti-Jewish laws were very strict, and they couldn’t work or go out freely because of the curfew. They wore the yellow star, but when Simone wanted to go out later, after the curfew, which was 8 p.m., she wore a jacket without the star. What helped them was that neither of the girls “looked Jewish”, Simone’s daughters told us, which enabled them to move around Paris and its suburbs widely after 1942 (and, for example, to traffic in false papers to help Jewish families or children, in Simone’s case).

Fania, Simone and Georgette’s mother, was arrested in June 1942, a few days after the compulsory wearing of the yellow star, and disappeared without her daughters knowing where or how. These two color pictures taken by French photographer André Zucca in 1942 (on the left in rue de Rivoli and on the right in rue des Ecouffes, in the IVth arrondissement), show Parisians wearing the yellow star, and Fania could have been one of them. André Zucca worked for the Germans, with a press card, a pass and, above all, Agfacolor film. In particular, he worked for the collaborationist magazine Signal. © BHVP / Roger Viollet

Simone: Tell me, Georgette, what do you remember of our last days with Mom?

Georgette: Not much. I don’t think we were with her in 1942, but I don’t remember if we were already in UGIF homes.

Simone: In 1942, she was arrested, in June like all those women, Jewish and foreign, I suppose she was gassed at Auschwitz, like most of them…

Georgette: Foreign? Why wasn’t she French like Daddy?

Simone: They weren’t married… If they had been, she could have taken her husband’s nationality and be French, that’s the law. But no, she stayed Russian or Polish, because of her bad luck.

Georgette: Do you realize that with our father off to the southern zone, we’d been alone in Paris since 1942!

Simone: Yes, and we were so young. Our father, we had to wait until we came back from the camps to find out he was dead.

Georgette: He was undoubtedly a member of the Resistance… and so were we, especially you, in our small way. Do you remember the false papers?

Simone: I was already on rue Vauquelin, when a sixth section was added to the Éclaireuses israélites movement, the Service Social des Jeunes, whose “code” name was the “Sixième”. Yvette Dreyfus, who was with me — I think she was 16 — was put in charge. And I belonged to this clandestine organization, which operated within the framework of the UGIF.

Georgette: Initially, the group collected children who had not been arrested during the Vél’d’hiv roundup. Some children had been in hiding for three days or more, and they were terrorized when they saw them enter, because they thought they were being arrested…

Simone: Three days? It was rather five, I was in despair over all this. The roundup took place on a Thursday, and the methodical search for the children didn’t begin until the following Tuesday. Some of the children were French, but many others were born of foreign parents (Polish, German, Austrian) and didn’t speak French, so it was very complicated.

Georgette: You and your group took them to “l’orpho”, the orphanage on rue Lamarck in the 18th arrondissement.

in the 18th arrondissement, a former hospice created by the Rothschilds for tramps who came to spend the night. In order to keep these children safe, they had to be given baptismal certificates, forged identity papers in order to obtain food cards, and cared for. We had to find hiding places to take them to the southern zone.

Simone: Oh yes, it was our duty – you were far too young. Have you ever heard of that forger from Paris, Adolfo Kaminski?

Georgette: Yes, I think his daughter wrote a book about him… he had started in 1943 to help the Jews of France during the roundups, then he continued, especially for children, he had created his own laboratory, even his family didn’t know about it.

Simone: We also made our own, you know, we had to create our own tampons… Our expert at the “Sixième” was called Sam Kugel. He made a hundred of these stamps, just with lino and erasers… And when it wasn’t for forged papers, it was for ration coupons, so we could buy food.

They fall silent again, deep in thought.

Simone: So, about Mum…, do you know today what happened?

Georgette: I think she was first held in the Beaune-la-Rolande camp, built by the Germans to hold prisoners of war. Hundreds of Jews, over 2,700 I believe, left Beaune-la-Rolande in 1942, either directly for Auschwitz in Poland, or first for Drancy – she was probably one of them, it was the time of the Vel’ d’Hiv Roundup. We don’t know on which convoy Maman was transported and probably gassed on arrival at Auschwitz in 1942…

Simone: At first, they told us she left by the 15th convoy…

Georgette: It’s less than certain. Remember how easily people misspelt her name — Uflanduk, Ifliandik, Zuckerman, Cukerman… That’s why the French Red Cross couldn’t help us after the war. She appears now on the list of convoy 451, but this 451 means that we know nothing about it, nothing, it’s just a number under which those who were deported without leaving any trace are grouped.

Simone: Maman, gone without a trace… All these convoys, I wonder if one day our grandchildren will know a little more about their fate.

Georgette: But otherwise, from 1942 until our transfer to Auschwitz, we were in contact with our family, well, especially with our aunt. The Germans wanted to force her to confess that she was Jewish, like our uncle Jacques, her husband, whom they had deported on the first convoy in 1942, but she was intelligent and kept her head on her shoulders. She didn’t let herself be intimidated and she wasn’t arrested: all because her Russian name, Ifliandik, once transcribed, could be written differently, with “u”, “e”…

Simone: Yes, it could be written differently and not sound Jewish… I don’t like that story. Ifliandik is Mom’s name, Mom’s real name, the name under which she was born… and which led her to Auschwitz.

A serious young girl, Simone during the war (date unknown) © Horowitz family archives

Arrest

Simone: Do you realize that with only a few weeks to spare, we could have been liberated at the same time as Paris?

Georgette: Yes, of course…

Simone: Do you remember July 22nd 1944? When we were arrested? Me on rue Vauquelin and you on rue Louveciennes.

Georgette: Yes, I remember, it was a summer morning. There were thirty-four of us children and six counselors, who were rounded up and later deported.

Simone: It was July 22, 1944, the heat was sweltering and we were all tired. 350 children were taken to Drancy that day. And us with them…

Georgette: We were arrested on the 22nd too, and taken to Drancy in a tarpaulin-covered lorry by four Germans who arrived in black traction. I found you there the next day.

Simone: They were Frenchmen who took me, I’m sure of it, Frenchmen, even if the friends deported with me assure me that they were only Germans. I vividly remember seeing this French policeman with this K.P. sign they called Kap, and his navy blue uniform. They just didn’t want to accept the idea that the French were involved in this kind of disgrace and so blamed the Germans. We were arrested very early in the morning, it was almost dark.

Simone: It all happened so fast! The Germans, accompanied by the French police, arrived and captured us! They arrived around 5 a.m. and rang the bell. Madame Kohn, our concierge, opened the door thinking it was a resistance fighter passing through looking for shelter, as sometimes happened. An instructor came and woke us up, telling us that the Germans were there. We didn’t believe her, thinking it was a bad joke, but when we heard their voices, the harsh reality caught up with us.

Georgette: The Gestapo didn’t give us time to pack anything; they took us straight to Drancy. So, from Louveciennes to Drancy, we made the little girls believe we were taking them on a bus ride… We made the 150 children sing all the way.

Simone: Yes, we too sang the Marseillaise and the Internationale in the trucks. We couldn’t let it get us down.

In Drancy

During the Louveciennes roundup, the center’s children were deported, as were the center’s director and his family. On arrival at Drancy, the director, Mr. Louy, and his family were released as “non-Jews”. Shortly afterwards, convoy no. 77 took these children and those from other UGIF centers to the Auschwitz-Birkenau extermination camp. All the children deported by this convoy were murdered in the gas chambers on arrival, and only the instructors and older people were employed in the labor camps: only Georgette Zuckermann and Denise Holstein survived.

This document lists the names of the children taken to Drancy. The words “Libéré le même jour” (“Liberated the same day”) appear next to the names of Mr. Louy’s family. At the bottom are the names of the staff, including Georgette Zuckermann. Paulette Szklarz (6), who was hospitalized at the time, and Martine Brust-Szwarcbart (also 6), who was saved by her 15-year-old brother, a member of the Resistance, in January 1944, were not taken to Drancy.

© Mémorial de la Shoah/Archives nationales de France

Georgette: We stayed at Drancy from July 22nd to July 31st.

Simone: No, until August…?

Georgette: But on the 3rd we were in Auschwitz, I think. No, I assure you, we were deported on July 31st.

Simone: Okay, so we were there for about eight days.

Georgette: We were housed in the first room on staircase seven. That’s what they called the room where they parked us…

Simone: Yes, I remember it, a vast room of bare concrete… When we arrived at Drancy, we learned that we were classified in group B. They wrote it on our cards.

Georgette: That’s right, it meant that we were Jewish and could be deported immediately, unfortunately…

La fiche de Drancy de Simone avec son adresse à Gennevilliers

© Mémorial de la Shoah / Archives nationales

Simone: So we were prisoners at Drancy. It was an unfinished building. It must have been built as a block of apartments, apartments or something like that.

Georgette: Yes, there were very large rooms, bare walls. The staircases were built, cement staircases, going from one floor to the next. I remember it well. We had nothing to do, except gather round to be counted. We went out into the courtyard once in a while, just to walk around. There was no activity, nothing.

On Georgette’s card in the Fichier des enfants de Drancy, we find her internment number, 25 493, and just below it “+ 92”, which corresponds to the last two digits of her sister’s internment number (25 492). It shows the date of deportation, identity details and a large “L” for “liberated”. On the back is her aunt’s address on avenue de la Porte d’Ivry, and the news of Georgette’s survival had already been announced (and no doubt communicated to her family) on June 11, 1945 by two other girls who left on Convoy 77, Simone and Lison Bloch, who were in Kratzau with Georgette and reached Paris before them. This shows how information circulated in the immediate post-war period. © Mémorial de la Shoah / Archives nationales

Simone: But at least there was no forced labor there.

Georgette: Not there. No, not there. Not in Drancy

Simone: Yes, it was just a collection point for people to be sent to Auschwitz. So there was no work. There were just people who said they worked for the UGIF and who were trying – I know now that they were trying – to find out where our relatives were, but we were afraid that they would use this information to arrest them.

Georgette: We never gave out any of that information. At least the older ones, the older children, didn’t give any of that information about where their parents or family and friends were.

Simone: Yes, we tried not to say anything, because we knew they’d end up being arrested. So that’s the only thing we did at the time. It only lasted eight days, so…

Georgette: Do you remember the guards at Drancy?

Simone: Yes, they weren’t so cruel at Drancy. The Germans, they scared everyone with their barking dogs, they weren’t as cruel as that, I mean we never saw a life-threatening incident

Georgette: But there wasn’t enough food and it wasn’t adequate. We survived because the others received parcels from their families and shared the food with us.

Simone: In the end, during the ten days we spent in Drancy, we didn’t really suffer, apart from being incarcerated and not knowing what had happened to our father.

On this page of Drancy’s cahier de mutations n°15, we find the names of several of the girls from Vauquelin or Louveciennes deported by convoy 77, including Violette Parsimento, Yvette Dreyfus (Lévy) and Neja Godztein. They were all housed in staircase 7 in room 1. © Mémorial de la Shoah / Archives nationales de France

Georgette: Yes, we had news of him through a cousin, but from one day to the next, we had no more news. We knew he was in the south, in the Lyon region, in the Resistance.

They stop and look at each other, silent.

Simone: We learned much later that he had been arrested on June 10, 1944 by the German police and incarcerated in Montluc prison. He was executed shortly afterwards as a hostage along with thirty-two Resistance fighters, possibly for sabotage. We never really knew what happened to him.

Georgette: Let’s not talk about it now, I can’t think about it…

Deportation from Drancy to Auschwitz

Georgette: So, eight days later, they rounded us up and put us on a train, which I think was nearby. Well, I don’t remember very well.

Simone: Remember, they put us on a bus to take us to the train, to the Bobigny station.

Georgette: Anyway, they took us to a cattle train, 60 to a car. Living conditions in those wagons were appalling. It was overcrowded and the overcrowding was terrible. We ate only what we had. There was barely enough water. There was only a bucket to relieve oneself with some sort of, we put a curtain – a sheet around it to have some form of privacy. They only emptied it once a day, when they opened the wagon, when they stopped, and that was usually at night.

Georgette: At night?

Simone: No, I’m sorry, during the day. At night, the train ran. During the day, most of the time, it was stopped.

Simone: I was very lucky. I’d managed to sit on some packages near the window. There was a tiny window with a bar and I could see what was going on. I remember that at one point, some people I knew, older men who were part of the train I’d seen in Auschwitz…

Georgette: In Auschwitz?

Simone: No, of course, in Drancy, they tried to escape, walking naked to the first car because they had tried to escape. There was crying and it was horrible. They only opened the doors once a day. And there were, of course as I said, these 350 children. They asked the older girls to look after the younger ones. I took care of a little boy, three or four years old, I think.

Georgette: I don’t think I remember any younger children.

Simone: That’s true, they were probably with their mother. But there were a lot of three- and four-year-olds who had no one. Maybe five, also five.

Georgette: I think three days. Something like that. And we arrived in the middle of the night. It lasted maybe four days.

Simone: At that time, it was very difficult to have any notion of dates, because you know, you didn’t have a calendar. You leave and this trip seems to last forever. So we arrived, but I know, I remember, we arrived in the evening, late. And they told us to get off.

Georgette: I don’t remember how many cars there were, just I know, I found out later that there were 1300 deportees on that train, so probably 20 cars.

Simone: The only thing I knew was that we had to get off, without taking anything with us. And that we had to jump off. And of course, some people were afraid to jump off, the older ones.

Georgette: There were Germans. “Raus, raus!”, you remember, the way they shouted. With dogs. And there were prisoners in striped uniforms. I think there were one or two Frenchmen with stripes, but I didn’t hear them. Others did. So, some Frenchmen told some people what was going to happen.

Simone: We jumped off the train, and I remember that the little boy who was with me had no shoes, so I had to carry him onto the platform. And when I got there, when we got to the head of the line, there were, there were two Germans with dogs, German shepherds. And Mengele was there.

Georgette: We had other opportunities to see him, he was there at every selection.

Simone: He had a stick and was pointing to the left or the right. He asked me in German if the little boy was mine, and I replied, “No.” I guess he understood that he wasn’t my child. I was only 18, barely 18. So he said, “Let him go.” And I let him go, and they took him, I don’t remember, to the right, with all the other little kids, and I went to the left, which was Mengele’s right. And so there were about, I’d say about 60, 70 women, maybe less, I don’t know, maybe 50, who came to the camp. All the others were gassed. Because the men were taken to a different area. So I, it was, they went to one, they were sent to another place. And then we ended up together, taken to a big building.

Georgette: I too was lucky enough to go to the right, when I was only fifteen.

Simone: The director of our home didn’t want to leave the younger children because she’d been looking after them for some time. She wanted to leave with them. And they all ended up in the gas chamber. And of course, the mothers didn’t want to part with their children. That’s also true. But some of them thought that if you were separated, it was better for you to go with the youngsters and for them to go with the others, to the other side, because if you put the youngsters together, the ones who were capable, strong enough and able to work, would have a better chance of surviving, or something like that. It was an innate instinct to go, and besides, we didn’t have much choice.

Georgette: So Mengele did the Selektsia, and he chose me and my sister…

Simone: …and many other young women.

They remain silent for a long time.

Simone: Anyway, it was night, and we were taken to a big place, a big building. It looked big but, of course, after being confined in a cattle car for three or four days, I mean anything could look bigger. We were told to strip, to leave everything we had. Then they shaved us, took off all our hair, and sent us to the next room where we took a shower, a cold shower, no soap, no towel, then they gave us rags to put on ourselves. For some reason, we kept our shoes on at that point, and I had a good pair of shoes, a very good pair that had belonged to my father who was quite short and I was probably taller than him at that point. So I kept those thick leather shoes. And that helped me for a long time. So we got dressed, then they took us to the bunk where we were supposed to sleep. It was in a long wooden building, not the brick one we later saw at Auschwitz. In the center there was a wall, like a long wall, but not a wall, there was some kind of pipe inside. And they were heating a little bit, at one end and that was supposed to heat the whole place. It divided the place in two, but you could step over it. It was very long. And on each side, there were bunks, three-tiered bunks, where we put four to six people per bunk, depending on the density of the camp.

Georgette: That was the first night.

In the camps

Georgette and Simone only stayed together in Auschwitz for about three months, between the beginning of August and October 27, 1944. They were both ill, passed through the infirmary, but escaped selection and the gas chamber. In October, Georgette joined the group of deportees, mostly women, who were sent to a satellite camp of Gross-Rosen, in the Sudetenland, at Kratzau. From then on, their paths diverged, as Simone remained in the Auschwitz infirmary until January 1945.

Georgette: I only really remember Kratzau. But in Auschwitz, didn’t you have a routine when it came to work?

Simone: Not until I got sick.

Georgette: Did they count people three times a day? Like we did?

Simone: Yes. The only type of work I remember was those who volunteered for medical work. They were separated from us and taken to Auschwitz I. Otherwise, no, I don’t remember.

Georgette: Auschwitz I?

Simone: I remember one day, and this was before I was sick, they took us to the other camp, Auschwitz I. We were in Birkenau, but we didn’t go there. We were in Birkenau, Auschwitz II. It was about, I’d say

three or five kilometers. It’s hard to say. We got to Auschwitz, and there we took a shower.

Georgette: Why? The shower in Birkenau didn’t work?

Simone: I don’t know why they took us there. In a way, that’s what saved me afterwards, because I knew how to get to Auschwitz, I even knew how to get to the village of Auschwitz.

The village of Oswiecim (German: Auschwitz) is a short distance from the first two camps, which were developed near the railroads. In January 1945, Simone hid outside Birkenau in a building close to the village. © US Holocaust Memorial Museum

Georgette: Then you got sick.

Simone: Yes, I went to the infirmary and stayed there until…, and I think that lasted about, oh, I don’t remember, a week or two. But in the end, I caught either typhus or typhoid. But I had to stay in isolation in that infirmary.

Georgette: I caught scarlet fever like all the other people who were with us. But we recovered and returned to the camp.

Simone: In October, the whole camp was selected for the gas chamber, including our infirmary.

Georgette: I’ve always wondered how you didn’t get selected, since you’d been in the infirmary for weeks.

Simone: I was still quite strong and didn’t show any exaggerated signs of emaciation. So I…, anyway, they let me stay there.

Georgette: No exaggerated signs… One of the terrible things about the camp was that we were starving, but we always talked about what we’d eaten before, and what we’d eaten after.

Simone: It was really torture, but we couldn’t help it.

They’re silent for a long time.

Simone: So, at the time of this selection, they also extracted the able-bodied from the rest of the camp, all the able-bodied from my barracks, many girls and women, like you, to go and work in Czechoslovakia. That’s where we were separated.

Georgette: I went there with all our friends and so I lost sight of you.

Simone: So I ended up with just one French girl. At the very end of October, they stopped using the crematoria. They only burned those who were dead, for all sorts of reasons. So it was a break for us, who had managed to survive at the time.

Georgette: But what did you do with your days then?

Simone: Nothing! We did nothing! We just sat around, most of the time outside, unless it was raining.

Georgette: Did you have any friends? Anyone in particular who might have helped you?

Simone: Not really, I was ill for so long that I was probably in no state to do anything. I slept more than anything else. Then they made us walk. That was in January. January ’45. There was snow on the ground. It was very cold. They marched us around for a while. All of a sudden, after a while, we found ourselves alone. The guards had left.

Georgette: Were there any Russians?

Simone: We could hear the cannons, the Russians couldn’t have been far away. We were really scared. We didn’t know where they wanted to send us, but we found ourselves alone. So we finally decided to go into the houses. There were houses on the road. And so some of us French girls – there were three of us French girls together at the time – went into one of the houses. There were already a few people there, in a basement. And we stayed there for a whole week, with a quarter-pound of bread.

Georgette: When you started coming out of Birkenau, how many people were with you?

Simone: It was a whole, I mean there were quite a few, but I couldn’t give a number. It was a long line. The guards left without giving us any information. They had, apparently, they had trucks around, but they just left. We were sort of free. But as it was really the front at that time, pretty much the front of the war, we knew we shouldn’t stay out and try to escape.

Georgette: So in the end, how long did you stay in Birkenau?

Simone: Well, from August 2 or 3 to January 5 or 6, five months. And you, tell me…

Georgette: It’s a long story.

Georgette at Kratzau

Georgette: As you said earlier, in October 1944, there was a selection for the gas chamber throughout the camp, including the infirmary, and you escaped. That’s when they deported a lot of girls and women to work in Czechoslovakia.

Simone: At that time? And what did they give you to work there, clothes?

In November 1944, two women who had been deported at the same time as Georgette, Anna Sussmann and Margot Ségal, managed to escape and reach Switzerland. They alerted the Red Cross, who then sent a parcel of food: it was their testimony and that of Yvette Lévy, who was in the same camp as Georgette, that enabled us to imagine what life was like in Kratzau. We assume they went through similar ordeals. If Georgette worked making pistols, the machines gave off heat, which was an advantage for the women in the workshop there, as it wasn’t as cold. Some women painted grenades with highly toxic products and were therefore entitled to a quart of skimmed milk, which they didn’t drink because they thought it was poisoned. Some women carried out sabotage actions: by banging on the machines from time to time, they could block the operation of the factory and stop the production of weapons temporarily, but that was all – the risks were too great.

Georgette: This selection took place on October 27, 1944, but strangely enough, we actually took a shower – a cold one, of course – and there was no gas. They took away our clothes, disinfected us and gave us new clothes: a shirt, a pair of panties, a summer dress, a sort of light overcoat, a pair of socks and a single pair of flat shoes that didn’t necessarily fit. We didn’t have a towel or a change of underwear, so if we wanted to wash our one pair of panties or shirt – without soap, of course – we only had a summer dress to wear in November! After two weeks’ work in the factory, we were appallingly dirty. When we were given rags to clean the machines, we used them to make turbans for ourselves (we’d been shaved before leaving Auschwitz). Towards the end of November, we were given clogs, a kind of wooden slipper, open at the back, which made it impossible to walk in mud or snow.

Simone: And on the road, did you eat?

Georgette: We had to share a small piece of bread with a slice of sausage. That was all. Then we were taken in a cattle car in which we traveled 3 days to Czechoslovakia. We arrived in the Sudetenland, which had been emptied of its Czech inhabitants and colonized by Germans. The camp was called Kratzau.

Simone: How many of you were there?

Georgette: One thousand women of all nationalities, watched over by forty SS men. They took us to work in an armaments factory set up in a mountain village an hour’s walk away. Every day we had to climb up there, barefoot in flip-flops. We had no socks, no tights, not even rags on our feet. The temperature dropped to -15°C or even -20°C, and sometimes we were knee-deep in snow. There we were supervised by German foremen and forewomen with Nazi badges. In fact, it was an old weaving mill that had been converted into an armaments factory by the Germans. The work was hard, especially if you were on the night shift. That said, working in a factory was a blessing, even if it meant working 12 hours a day, while others worked in commandos, breaking stones to level the road, or in the mountains, sorting parts to make rifles. Work in the workshops was not unpleasant, we were relatively unsupervised and treatment by German and foreign foremen was decent, with a few exceptions. The other workers were strictly forbidden to talk to us, but in several workshops, they gave the women bread, fruit and the occasional newspaper to read. As for work, bonuses were given to the women who worked best. They were usually given an extra 200 grams of margarine and a little jam, and sometimes a small packet of washing powder.

Simone: What was the camp like?

Georgette: They were big buildings, with a dormitory on the second floor. There were bunk beds on three levels, two to a bed with a straw mattress and a blanket for two. The women supported and organized each other, collecting items to improve their living conditions, or food here and there.

Simone: Tell me more about what it was like in the factory.

Georgette: We got up at 3:30 a.m. and the beds had to be made. At 4:15 a.m. there was roll call in the dormitories, then “Exodus” in the courtyard to fetch breakfast, each in turn. Breakfast consisted of soup made from water and potatoes or vegetables, thickened with raw potato peelings. We were given ¾ of a liter per person. At the same time, we were given our daily ration of bread, some 250 grams with 5 to 10 grams of margarine, a slice of sausage or a spoonful of jam, beet marmalade. At 5 a.m., roll call was taken in the courtyard for those leaving for the factory, where the workday began at 6 a.m. and ended around 6 p.m. There was no lunch. On returning to camp, there was a second roll call in the courtyard, followed by a waiting period for soup to be distributed. The evening soup, about a liter, was also made with potatoes, but was thicker and usually contained whole potatoes in their skins, mixed with a few beets. Once a week, we got the usual potatoes with a little meat sauce and, occasionally, onions. On Sundays too, we were treated to potatoes with a little meat sauce. By 9pm, we were in bed.

Simone: When were you liberated?

Georgette: On May 7, 1945, when we had little work to do, we were gathered in the village courtyard, where we slept, and the factory manager told us that the war would soon be over. It was very strange, the day before we had been slaves in his factory, and now he was wishing for us to be able to return to our respective countries. On the night of May 8-9, 1945, the SS disappeared, leaving their uniforms behind, but the camp was mined and we didn’t dare move. On May 9, 1945, Czechoslovak partisans entered and cleared the camp of mines. In the afternoon, the Russians arrived.

Simone: The Russians…

Georgette: For years I couldn’t talk about those days… I told Denise something once, long after…

Simone: What was it?

Georgette: You know, at that time, we spoke a bit of Russian, didn’t we?

Simone: At least, we understood it.

Georgette: Exactly. One evening, I heard voices coming to our shelter and they said, in Russian, and I understood, “let’s come back at night and have some fun!” I shouted to the girls to run, run and hide in the fields, and I run but some girls didn’t follow us and were dead the next morning, raped.

They stay silent for a while, looking at each other.

Simone: How did you get home?

Georgette: Ten of us left by truck to get to Prague. A friend and I stopped at one or two farms, but we couldn’t find anything to eat. I know that the mayor of Kratzau made a note for some of the girls inviting everyone to help them get home, but I didn’t get anything like that. On the way home, we stopped from time to time, when we could. Nowhere did we receive a warm welcome. Russians and Americans alike asked us to sleep with them in exchange for food. We refused, we had to make do. Some of our comrades died on the way back. When we arrived in France, we were greeted with contempt, we were disappointed, bitter and sad, people weren’t welcoming at all.

Returning to France

Georgette: And you, in Auschwitz, once you finally recovered a little and felt strong enough, what did you do?

Simone: Well, I waited until I could be repatriated. We spent the days walking and walking and talking. Talking and talking. And at that time, there were a lot of other French people, mostly men.

Simone in 1945, her hair still very short after being shaved in Auschwitz

© Mémorial de la Shoah / Adeena Horowitz

Georgette: I think I remember you telling me about it… The French Red Cross managed to round up enough Auschwitz inmates, forced laborers from all over Europe, and used a cattle train, to return to France via Russia. You first went to Krakow, where the train departed from. They kept you in Krakow for about a week, in a school.

Simone: Yes, exactly. They gave us some Polish money, and we tried to supplement our diet. We wanted to find eggs and cook them. So we bought eggs, but no matter how many we cooked, they were always hard-boiled. Until we realized they were selling us eggs that were already cooked, already hard-boiled.

They smile.

Simone: We made things, until the train came. Then, when it arrived, they put us on it.

In Krakow in 1945 © www.herodote.net

Georgette: I don’t think you had any papers at the time. They just had a list of people. You didn’t have any papers of your own. So, you couldn’t get very far.

Simone: Yes, we couldn’t do much because we never knew if we didn’t have some form of identification. So, where was I? Ah yes! We were put on a Soviet train, in cattle cars again, but certainly not 60 per car. We had enough room to all lie down, 20 or 25 people on the floor. Whenever it was time for meals, the train stopped and they prepared food in the wagons. We went like that from Krakow to Odessa, through the Ukraine.

Georgette: It was all under the aegis of the Red Cross, wasn’t it? There were a few Frenchmen looking after the prisoners and Russians, of course, guarding the wagons.

Simone: Exactly! And it was very, very sad, because there were all these Russians coming to the cars with their rags and trying to sell us something, to buy something from us: we had nothing and they had less than nothing of their own. And that lasted about a week until we got to Odessa, where they put us up in a school. There we met a lot of people from the French Red Cross. They gave us papers, clothes and food. In other words, they gave us back our identity and our self-esteem…

Georgette: How long did the Russians keep you there?

Simone: Well, we were there for about a week. Of course, we weren’t really allowed to move around. The Russians were always very careful and didn’t let us mix too much with the others. Of course, we didn’t know the language either. Finally, we waited for the boat to arrive, a British ship that was going to take us back to France, to Marseille. And remember, it was still wartime, so there were a few organizational problems… And of course, we were afraid of being shipwrecked by a torpedo or something. There was always that worry, and they made us do training exercises all the time to prepare us for all eventualities.

Arrival of a British liner in Marseille, April 5, 1945.

Coming from Odessa, it brought back some 1,600 prisoners and around 60 deportees from Poland, Ukraine and East Prussia. © La Provence (photo DR)

Georgette : Ça devait être à la fin du mois d’avril. Et le voyage a dû durer environ dix jours. Vous êtes donc arrivés à Marseille le 1er mai.

Simone : Exactement ! Je m’en souviendrai toujours, parce que le 1er mai est un jour férié. C’est notre fête du travail. Je me souviens donc avoir atterri le 1er mai 1945. A Marseille, nous avons bien sûr été rassemblés dans un bâtiment et la Croix Rouge était là. Ils nous ont demandé ce que nous voulions faire. Nous décidions où nous voulions aller et ils nous y emmenaient.

Georgette : Donc, théoriquement, tu voulais retourner à Paris, mais tu as d’abord demandé s’ils savaient ce qui était arrivé à notre père. C’est ça ?

Simone : Effectivement. Ils ont répondu qu’ils le découvriraient. Et le lendemain, ils m’ont dit que mon père avait été tué, qu’il avait été arrêté le 10 juin 1944 à Lyon, emprisonné à Montluc et fusillé parmi d’autres otages moins d’un mois plus tard, le 8 juillet — alors même que nous étions encore libres, Georgette ! Et nous n’en avions rien su ! Je n’ai pas besoin de dire le choc et le traumatisme que cela a provoqué, tu as dû ressentir le même lorsque tu as appris la nouvelle. Mais je ne savais pas quoi faire. Je ne voulais pas aller à Paris, mais ma tante y était toujours, et je me demandais si je devais y aller. Un ami m’a proposé de m’accueillir chez lui pendant deux semaines, jusqu’à ce que je reprenne contact avec ma tante ou mes amis à Paris.

Georgette : Et c’est ce que tu as fait. Tu es retournée à Clermont-Ferrand avec lui, dans sa famille. Il avait sa femme et ses enfants, qui avaient à peu près ton âge. Tu es restée avec lui environ deux semaines, puis tu es partie vivre chez une de ses amies qui vivait dans les montagnes et tu es restée avec elle le reste de l’été, toujours près de Clermont-Ferrand où tu as repris tes études à l’automne.

Simone : Je n’avais pas étudié depuis presque un an, alors j’ai voulu reprendre mes études, les réviser, parce que je devais passer ma deuxième partie du baccalauréat. Et je me suis préparée à entrer à l’école. Je savais que j’allais retourner à Paris, mais je ne voulais pas aller chez ma tante. Alors je suis allée dans un autre orphelinat, sous la tutelle de l’OSE.

A view of the “Hirondelle” house after the war, one of the homes run by OSE. © www.judaisme.sdv.fr

Georgette: The OSE, l’Œuvre de secours aux Enfants… They were in charge of homes for orphans during the war, orphans or those hidden by their parents, and then, after the war, in addition to these children there were the few who, like us, had returned from the camps. So that’s where you went, to one of them, not far from Versailles. Because that’s where the older children went. And you lived there for a year, if I remember correctly… And then so did I.

Simone: …Not quite a year, but yes, that’s right…

Georgette: …As for me, we were liberated at the beginning of May 1945, on the 8th, I think, when the war ended. It took us well over a month to get back to Paris…

Simone: May 8, 1945 — yes. And I don’t know exactly what happened to you right after that, because you were never very clear, nor were your friends who came back with you. But you came back with the Red Cross, and first you moved in with our aunt, where you lived for while…

On her return, when her aunt had just found her and she was going to stay with her, Georgette underwent a medical examination. Her condition was judged to be “average”© dossier DAVCC 21 P 602 353

Georgette: Oh, then I decided to go to one of those homes that took in orphans from the camps, and by an awful coincidence, it was right where you’d been arrested, on rue Vauquelin. You went off to live on your own in Paris, rented a room and went back to school.

Simone: I returned to Paris at the end of the summer of ’45, at the end of September. Classes started again in October. Before the start of the school year, maybe a few weeks before. I went to see our aunt, but I didn’t want to live with her.

Situation after returning from deportation

After the war, Georgette and Simone returned to Paris and tried to sell their childhood home to earn some money, but as minors they needed a guardian, which explains why Georgette didn’t sell it until after Simone had left for the United States.

Simone: Yes, the house – our house – was rented for a long time. And we left it that way until we sold it, many years later, when I was already in America. My sister took care of it. It was sold.

Georgette: When we came back from the camps, we found everything intact.

Simone: Just as we left it. Nobody had touched anything. Shortly after the end of the war, my sister and I were back in Paris. But we were both still minors. So to do what we wanted to do, rent or, you know, we wanted to sell the furniture and machinery that was there, so what we did, we had to get, what do you call it, oh, someone who was responsible for it.

Georgette: We needed a guardian.

Simone: We were lucky: I asked the friends I grew up with, this family I knew very well, whose children — the oldest daughter, Denise, was in my class all through school, even university, and her mother, both they were doctors. She volunteered, I asked her and she said yes. My aunt, I didn’t want my aunt as my guardian because we didn’t get on very well and there was a lot of friction between her and my father, and I didn’t want these memories to affect my life.

Georgette: We sold everything to a man who was interested in using the factory, and our aunt took care of everything. I went to live with my Aunt Doba, who wanted me to go back to school.

Simone: It has to be said that you first returned to the Rue Vauquelin hostel, like many other young survivors. Rue Vauquelin is where I was arrested.

Georgette: And you?

Simone: Well, for a while, I lived with the director of the home I went to. She was there for about a year, not quite, so I was there for just under a year. And I rented the maid’s room she had upstairs. I stayed there for, well, less than a year, I think, until I found myself renting a room in an apartment with an older lady, not far away. But I was back in school. I finished high school with the second part of the baccalaureate. Then after that, as I wanted to go to medical school, I had to do a year of basic chemistry and biology, which is compulsory, which is university work. And then I went to medical school. And I took care of myself, basically.

Simone pauses for a moment, then continues in a low voice.

Simone: And then, in November, remember, we had to go to Montluc… It’s a moment I can’t think of without horror, despite all these years…

Georgette: We had to identify the bodies of the hostages shot at Montluc. Our father was dead, we’d been told, but we had to be sure it was him…

Simone: And when they showed us his dentures…

They remain silent for a long time.

Georgette: Yes, I was devastated, I never got over it. I couldn’t study, I couldn’t concentrate. I tried to work, but without success. Later, I decided to go to Israel because one of the boys I’d met in the hostel had gone there and I liked him.

Simone: Georgette, you drove me crazy not knowing what to do with your life, I warned you that you’d end up in Cyprus (that’s where most of the immigrant boats to Palestine stopped), and that’s what happened!

Georgette: I lost everything: my money, my clothes, my things. So I came back with nothing, and moved in with her aunt to try and “clear” my debts.

Simone: It was only then that I left for America.

Georgette: In 1947 or ’48, I think?

Simone: Yes, 1948. By then, I’d decided to leave France anyway. I couldn’t see myself living there after what I’d been through. There was an enormous amount of anti-Semitism. The French certainly weren’t ready to listen to the survivors, and of course, in America, they weren’t either, but… and then the Jewish community was non-existent. It was pathetic. It took many years for it to reorganize, so there was nothing for me. There was virtually no Jewish community left, if there was one, apart from the scouts I’d known before, the Jewish scouts I’d known, which I continued to frequent for a while.

Georgette: My reasons were probably not quite the same, but I also left…

And later…

Simone, when she arrived in the USA in 1948, did not immediately pursue her studies in Detroit, where she moved in with her cousins, but ended up at Hunter College in New York, where she obtained her Bachelor Degree.

She then had a job in a laboratory, but at a basic level, and stopped working as soon as she got married and started a family. © Horowitz family archives

Her husband, Herman Horowitz, was introduced to her in 1954 by his cousin. After living in New York, they settled in Philadelphia. They had three daughters, Sara, Myriam and Adeena. Simone became an American citizen in 1955 and never worked again, but she was a very active woman: she was an excellent cook, she loved music, she painted, she did a lot of crossword puzzles and logic games, and she also enjoyed sewing.

As you can see from this photo, she was taking a humorous view of her situation as a housewife! © Horowitz family archives

Leaving France in 1950, Georgette lived the rest of her life in Kent, Great Britain. At an early age, she married Dennis Mount in 1949, a police officer who was a British agent in Cyprus, it seems, and with whom she had a daughter, Michelle, in 1956. They later divorced and she married Mr. Gambrill in 1968, but he died of a heart attack in 1974 or 1975. She finally married John Cranham, a biology researcher, in 1978 and they lived together until his death in 2022. Strangely enough, on her last marriage certificate, Georgette added a middle name, Monique. The certificate indicates that her profession at the time was “senior officer local government”.

She and her daughter made several trips to the United States, where they met Simone. This photograph may have been taken during one of these visits.

Simone between her sister Georgette, Georgia, and her brother-in-law John Cranham, in the 1990s. © Horowitz family archives

But the war and especially the deportation weighed heavily on Simone’s life: “she wasn’t the happiest woman you could imagine”, she was an “angry” woman, “with a lot of anger in her”, her daughters told us, while Georgette, Georgia, would have come back stronger from the war – but for both of them, the trauma was enormous. Simone was happy with her life in America, happy to be in the U.S.A., even though she had great resentment towards France, which she held responsible for what had happened to them. When she came back from Auschwitz, she didn’t think she had any place left in this country, she didn’t want to stay.

However, she was always very clear about the fact that her neighbors in Gennevilliers had always been decent: they kept their homes and belongings intact until they returned, and protected their possessions. Furthermore, she returned to France after the war, twice, in the 1980s, which gave her a form of healing from all that anger. She had the tattoo of her Auschwitz deportation number removed. We don’t know if Georgette did the same with the number she wore: A 16833.

The two sisters struggled for years to assert their rights: having left France in the late 1940s, they were unaware that they could obtain the status of political deportees. They only learned by chance, in 1962, from an article in the press, that they were entitled to compensation. They continued to write to each other until 1995, but as neither of them lived in France or retained French nationality, it was difficult for them to assert their rights. According to their correspondence, Simone may have received something in connection with the death of her father, who was shot as a hostage by the Germans. Simone’s friend, Denise Lubetzki, helped them for years to cope with their grief and intervene to have their father’s name inscribed on the Porte-lès-Valence monument to the memory of the hostages shot there in July 1944, and their mother’s name on the list of the Gennevilliers inhabitants who were deported.

When Simone returned to France in the 1980s or 1990s, she revisited her home in Gennevilliers. She also reunited with her former deportation companions at their annual reunion.

The authors:

A group of volunteer students from classes 3A, 3B and 3C at Collège Pierre Alviset in Paris, under the guidance of their history-geography teacher, Catherine Darley:

Henri Alor, Julien Aunay, Lyne Beller-Tolve, Elio Causse-Feuillet, Nina Dao, Paul De Franco, Louise Denoit, Alexandre Derome, Inès De Villanova, Eva Dounovetz, Lucie Foubert, Lola Gomez-Le Du, Nina Khamdamov, Lucie Langet, Manon Le Merrer, Victor Louet, Mara Lefebvre, Elsa Marion et Emilia Pandolfi.

This work was carried out between October 2022 and June 2023.

Sources :

- Georgette Zuckermann’s file at the DAVCC: DAVCC 21 P 602 353

- Simone Zuckermann’s file at the DAVCC: DAVCC 21 P 572 806

- Simone’s testimony was recorded (in English) in 1995 for the Holocaust Memorial in Washington (USA).

- Georgette, for her part, did not record the story of her life, and in particular of what she experienced during the war, so we have only indirect accounts of what she may have experienced, from young girls who were probably with them in Louveciennes or rue Vauquelin and who, like her, were deported to Auschwitz and from there sent to the Kratzau labor camp: Germaine Helbrun (testimony recorded in 2007 in Cannes and preserved in the Alpes-Maritimes Departmental Archives) and Yvette Lévy (testimony filmed in 2004 by the Mémorial de la Shoah and the Mairie de Paris). The testimonies of Anna Sussmann and Margot Segal, who escaped from the Weißkirchen (Kratzau) forced-labor camp for Jewish women at the end of November 1944, are featured in an October 10, 2018 article by the Cercle d’étude de la Déportation et de la Shoah : https://www.cercleshoah.org/spip.php?article705

- The correspondence we conducted with Simone Zuckermann’s daughters, Adeena and Sarah Horowitz, and the interview conducted by videoconference (and in English) on February 14, 2023.

- Photos of Nevakh Zuckermann and Fania Ifliandik, and of Simone and Georgette Zuckermann, their daughters, supplied by Adeena Horowitz.

- 1931 and 1936 census of the commune of Gennevilliers.

- Aerial photos of the Couture d’Auxerre district at different times on the site https://remonterletemps.ign.fr/

- https://www.gennevilliers-tourisme.com/galerie/gennevilliers-cartes-postales-cetait-hier

- Nevakh Zuckermann’s arynanization file kept in the Municipal archives of the city of Gennevilliers.

Français

Français Polski

Polski