Violette Bar Siman Tov, 13 November, 1925 – April 1945

by Roy Bar Siman Tov

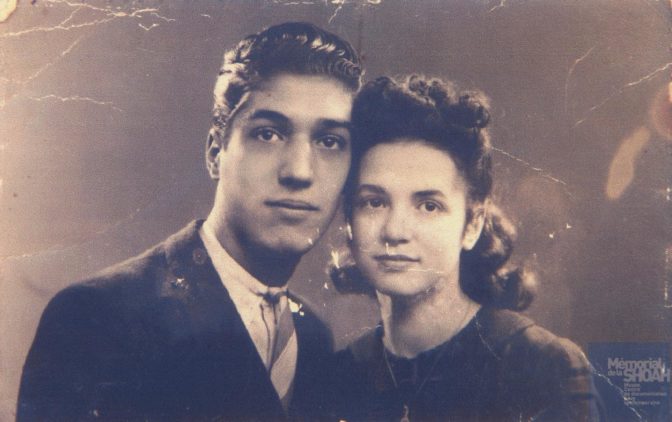

Photo of Violette with her fiancé, Elie Benso, reproduced by kind permission of Serge Klarsfeld

עבור קוראינו הישראלים הביוגרפיה זמינה בעברית תחת הגרסה הצרפתית

Introduction

In July 2017, I began researching the members of my family who perished in the Holocaust.

This research began prior to a journey of remembrance to Poland, and it has changed my life.

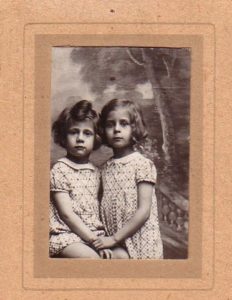

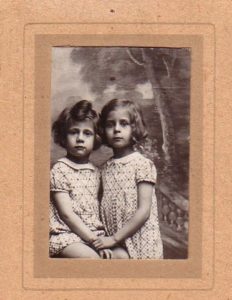

My paternal grandfather, Nissim Bar Siman Tov, was born in Tiria, Turkey. His parents were called were Yaakov and Srouta. My grandfather had seven brothers, one of whom was named Haïm (Victor). When Haïm grew up, he married Sarah. Together, they had three daughters: Violette, Jeanine and Louise. They were all killed during the Holocaust. I decided to focus my research on this branch of the family.

In the first stage of my research, I became captivated by the eyes of their eldest daughter, Violette. She appeared to be beautiful, elegant, kind and gentle, with a cheerful look in her eyes. Unable to explain it, even to myself, I felt a great bond with this young girl. I was eager to investigate further in order to find additional details about her.

In this biography, I have gathered together the results of the research work I conducted last year. These are based on testimonials from Violette’s family members and other people who knew her. They also include interviews with several women who knew Violette during the war and a number of archived documents.

As part of my research, I got in touch with and met the wonderful Barembaum-Costi family from France: Renée and Martine Costi and Martine’s daughters, Lise and Sarah (Sarah lives in Israel). After the war, Haïm was remarried to a woman, also called Sarah, whose first husband had been killed during the war. Sarah’s daughter from her first marriage, Renée, is Martine’s mother.

I thus discovered this amazing family, who helped me enormously in my research, in particular in overcoming the language barrier, since I don’t speak French, and in collecting new material. I was very moved to see that although we had no blood ties, the Barembaum sisters became involved in the research, were as curious as me to discover new details and also felt close to Violette and her sisters. I realized then that my family had grown.

The Bar Siman Tov family members in France

In 1922, Haïm (Victor) and his brother Rafael, aged 16 and 18 respectively, had refused to serve in the Turkish army. They secretly boarded a ship bound for the port of Marseilles, in France. The two brothers later married in Paris. Rafael and Ester had two little girls, Jacqueline and Solange. Haïm married Sarah and together they had Violette, Jeanine and Louise.

Violette and her parents, Haïm et Sarah

Violette and her parents, Haïm et Sarah

Jeanine and Louise, Violette’s sisters

Jeanine and Louise, Violette’s sisters

Paris fell into the hands of the Nazis in June 1940. Two years later, in July 1942, 12,000 Jews were arrested and deported to the Drancy transit camp. Among them was Rafael.

On September 23, 1942, Rafael was deported to Auschwitz on convoy number 36. When he arrived, the number 64484 was tattooed on his forearm. On February 1, 1945, he was deported to the Dora concentration camp in Germany. He survived there until the end of the war, working in the “Deks” commando unit. Sadly, he died as a result of being overfed when the camp was liberated by the Russian and American armies in January 1945. He is said to have been buried in a mass grave. His wife and two young daughters survived the war.

Haïm (Victor) was arrested on October 5, 1943 and transferred from Drancy to Alderney, one of the Channel Islands, on October 11, 1943. The reason that he was taken to this this particular destination could have been related to his Turkish nationality (if he still held it at the time) or because he declared that he was married to an Aryan woman (as he mentioned in an interview). These are the reasons cited by those who have studied the make-up of the convoy. The labor camp on the island of Alderney, which is in the English Channel, near to the French coast, had no gas chambers. Prisoners carried out forced labor, constructing fortifications for the Atlantic Wall.

While at this camp, Haïm made wooden shoes. He survived and managed to escape after making shoes for an officer’s wife. When Haïm returned to his Parisian apartment at 14, rue des Amandiers, he found it deserted. His wife Sarah and his two daughters, Jeanine, 7, and Louise, 8, had been arrested on March 7, 1944. They were deported to Auschwitz on convoy 69. The two little girls were sent to the gas chambers upon arrival. Sarah was killed in September 1944. Violette was not at home when her mother and sisters were arrested.

Victor (Haïm) Bar Siman Tov

Victor (Haïm) Bar Siman Tov

Violette

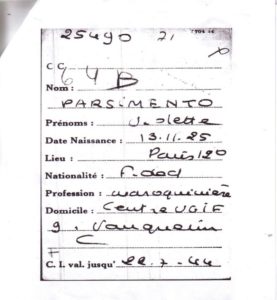

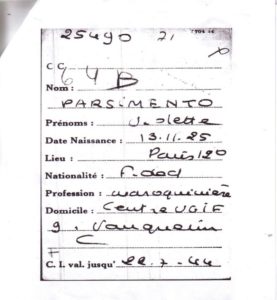

Haïm and Sarah’s eldest daughter, Violette, was born on November 13, 1925, in the 20th district of Paris.

I have tried to unearth more information about Haïm by every possible means. When I met Renée, Haïm’s daughter-in-law, I asked her if he ever talked about his daughters. Haïm, like many others, always refused to talk about his family that disappeared during the Holocaust because it was too painful for him. He died in Paris in 1972 and was buried in Israel.

In an interview with a Holocaust survivor who had known Violette during the war, Yvette Lévy, née Dreyfuss, I learned that Violette was a charming, sweet young girl with blond hair and a turned-up nose. Yvette described her with these words: “Those who remember Violette hold the memory of a very beautiful young girl”. From other witnesses’ accounts I learned that Violette had worked at processing goat skins in order to provide for her mother and her two younger sisters after Haïm’s arrest.

When I first met the members of the Barembaum family, they gave me information that describes Violette’s unique personality perfectly. Lise Barembaum said that when Yvette Lévy and Mathilde Jaffé recounted what had happened to them during the war, the two women stopped talking and then suddenly began again, saying that they wanted to talk about Violette’s story. It was as if they wanted to set Violette apart, to give her some kind of special recognition. I also wrote to Sylvie Turpyn, the daughter of Mathilde Jaffé, who told me that her mother adored Violette.

As mentioned above, Violette was not at home when her mother and sisters were arrested. At the age of 19, she found herself alone, with no family. She then decided to move to the children’s home at number 9, rue Vauquelin in Paris, where there were many other young orphans whose families had been arrested. The house was run by the UGIF (l’Union Générale des Israélites de France, a grouping of all Jewish assistance initiatives imposed by the Vichy Government and the German occupying forces), under an agreement signed between the UGIF, the Vichy government and the Nazis.

It was in this children’s home that Violette and Yvette Lévy met for the first time. Yvette was 18 when the German army conquered France. She was a Girl Scout leader and took care of Jewish orphaned children who had taken refuge in the home on Rue Vauquelin. Yvette recounted, during the conversation I had with her, that she and Violette boarded the same deportation wagon for Auschwitz and went through selection several times together in Birkenau. Yvette also confided that Violette never talked about her father and his arrest. She only ever talked about her sisters and her mother.

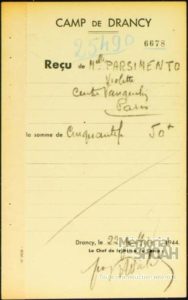

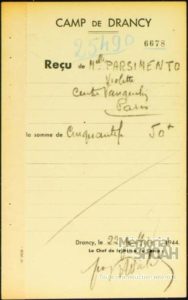

Violette was arrested during the night of July 21-22, 1944 during the Nazi raids on UGIF homes. When she was in Drancy, Violette decided to cut a lock of her hair and asked one of her friends to give it to her father in case he were ever to return home alive after his deportation. After the war, Haïm received his daughter’s lock of hair but never spoke of this episode and never revealed the identity of the friend who had given it to him.

During the war, Violette was engaged to a young Jewish man, Elie Benso, born in Paris on April 16, 1925. Yvette Lévy described Elie as an impressive, very handsome boy with brown hair and a very warm personality. Yvette added that Violette and Elie were in love and that Elie was very kind to Violette. When Elie learned that Violette had been arrested and that she was going to be deported, he could not bear the thought of being separated from her. He therefore insisted on being arrested as well, in order to travel with Violette on the train. The commander of the Drancy camp sent him home twice, but when Elie showed up a third time, he brought him into the camp, thereby condemning him to death. Elie was deported to Auschwitz together with Violette and was gassed as soon as he arrived, on August 3, 1944.

Violette Bar Siman Tov and Elie Benso

Violette Bar Siman Tov and Elie Benso

Identity card

Identity card

Drancy record

Drancy record

Deportation from France

The deportation of Jews from France too place from July 1943 to August 1944, under the command of Alois Brunner (Adolf Eichmann’s assistant in charge of matters related to Jews and their deportation to Paris). Brunner then, was in charge of the Drancy camp, as from June 18, 1943, where the Jews were detained before being deported. In 13 months, 21 convoys were sent to Auschwitz from France (convoys 57-77), carrying nearly 20,000 Jews, both French and foreign nationals. The deportation of Jews from Paris continued despite the Allied advance toward the capital. In late July, the Germans lost control of north-western France and the Allies were about to liberate the city of Le Mans, only about 125 miles from Paris.

Violette was arrested in the UGIF home during the night of July 21-22, 1944, and was deported with her fiancé, Elie Benso, on July 31, 1944, aboard the last convoy leaving Drancy – Convoy 77. The Americans were less than 100 miles from Paris. A month later, Paris was liberated from the Germans by French troops supported by an American division.

Aboard convoy 77, 1310 Jews travelled in cattle cars. Of these, 800 were gassed immediately on arrival in Auschwitz. More than 300 children, who had been rounded up from orphanages throughout Paris, were on the convoy. These children had to face this terrible journey by train. They cried non-stop, frightened, and suffering in the heat and from thirst. Yvette Lévy recounted that uniformed police officers forced the children, still in their pajamas, into the truck that was supposed to transport them from the orphanage to Drancy. It was very hot when the 1,310 people were made to board the cattle cars, with 60 people crammed into each car. “We were so close together, squeezed together like sardines,” Yvette said. There was only one bucket of water and an empty bucket to relieve ourselves.

In a written testimony, Yvette chose to discuss Violette, who traveled with her in the same wagon to Auschwitz. Yvette recounted that although she was born in Paris, Violette did not wear the yellow star “because she had Turkish nationality”. In addition, Yvette confided that Violette’s fiancé, who was also in the wagon, sang the song “La Paloma” in Spanish to Violette in an effort to reassure her and soften the conditions of her transportation before she arrived at Auschwitz. Reading Yvette’s testimony, I managed for the first time to imagine myself in this wagon, with Violette, sharing the same fear.

Violette’s convoy arrived in Auschwitz-Birkenau on August 3, 1944, one month before Anne Frank and her family arrived at the same camp. The Frank family was subsequently moved to Bergen Belsen. Anne Frank died a few months before the camp was liberated. Yvette wrote in her testimony that it is “impossible to forget arriving in Auschwitz”. The darkness of the night, the searchlights, the inmates in striped pyjamas, the yelling of the SS and the barking of the dogs.

Auschwitz and the transfer to Bergen Belsen

When they arrived at Auschwitz, the deportees on the convoy underwent the selection process and the Nazis assigned 183 women to the Birkenau labor camp. Mathilde Jaffé explained that Violette was pregnant on arrival at the camp. On October 27, 1944, Mengele reportedly made yet another selection. When he noticed that Violette was pregnant, he used her as a victim of his terrible experiments. Violette did not tell Mathilde about her what had happened until several months later, when the two girls met again in Bergen Belsen.

According to Yvette Lévy’s testimony, one of the young girls who was with them, Blima Bertha Krauza, found her father, a Mr. Paulish, who was a kapo at Auschwitz. Her father wanted to transfer her to a safer camp, but Blima did not want to go alone. Yvette Lévy said that the group of girls did not want to separate and that none of them volunteered to go with Blima. Then, at some point, one of the girls suggested that Violette go with Blima to Bergen Belsen and Violette agreed.

Many women from Auschwitz were transferred to Bergen Belsen between 23 August 1944 and early February 1945. In Bergen Belsen, these women worked in factories used by the Germans for the war effort, mainly aircraft and armaments factories. The women replaced the German men who had gone to the front

In November 1944, unusually strong winds destroyed the tents in which the women slept in Bergen Belsen. The women were transferred to the camp hospital. During this time, typhus and other diseases were rampant in all the camps.

When Mathilda Jaffe arrived in Bergen Belsen on January 4, 1945, she found Violette, who told her that when she was in Auschwitz, Mengele had cut her open and put a cat fetus in her womb.

Mathilde refused to testify to this. She only told her daughter Violette’s story, in confidence. It was this daughter who agreed to tell me the story after several conversations. In her statement, Mathilde said only, “I can’t talk about it, I’m too afraid to believe it”.

As soon as I learned of this, I tried to find out more information about Blima (Bertha) Krauze in the hope that she would be able to give me more information about Violette. I discovered through discussions with other survivors that her name was Blima Krauz. On the Internet, I found only one source where Blima’s name was mentioned: a lecture given in 2015 in which one of the speakers recounted the memories of his now deceased war-time wife, Blima. When I contacted the American association that organized the lecture, I learned that Blima had survived and moved to the United States where she lived until her death in 2011. Another opportunity to talk with a woman who shared Violet’s last moments was lost.

One question remained unanswered: what had happened to Violette, when did she die and under what circumstances?

In order to answer these questions, I contacted the Bergen Belsen Museum. I had little hope because I knew that the Germans had ensured that all documents concerning the deportees had disappeared before they left the camp. However, the reply I received allowed me to add an important piece to the puzzle that I was attempting to put together.

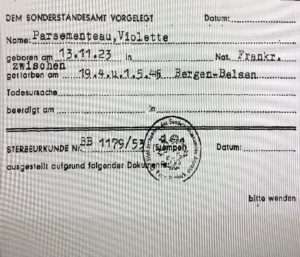

After the liberation of the Bergen Belsen camp on April 15, 1945, the French prisoners who were still in a decent condition drew up a list of the French who had survived. They completed this list on April 19, 1945, four days after the liberation of the camp. On this list, we find the name of Violette Bar Siman Tov (Parsimento) among the names of the deportees who survived the atrocities perpetrated by the Nazis.

I also discovered that at the end of April, the prisoners had drawn up another list. Sadly, Violette’s name was not on that one.

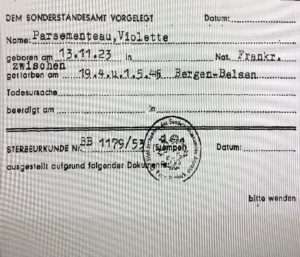

We can deduce with near certainty that Violette survived the war, but that she succumbed to one of the serious illnesses in the camp, her body having been seriously weakened by what she had experienced.

As for the exact time of Violette’s death, there are two possibilities:

- Violette had died in the concentration camp before the women were moved to the hospital, which was a few miles from the camp.

- She was taken to the hospital but died soon afterwards.

If the first hypothesis is correct, then according to the Bergen Belsen Museum, Violette would have been buried in one of the pits in the camp, on which stands a monument dedicated to the memory of the victims.

If the second hypothesis is correct, on the other hand, Violette would have been buried in the first row of the little cemetery next to the military base, which to this day is still next to the camp.

This military base was used as a refugee camp until 1950 and then became a British Army base until 2016. Since 2016, the site has been under the command of the German army and NATO.

We can therefore deduce that Violette died between the 19th and the 30th of April, 1945.

List of names of deportees who survived – the start of the list and the page including the name of Violette Parsimenteau (sic)

List of names that no longer appear in the second list – the start of the list and the page referring to Violette.

Violette’s death certificate

Conclusion

Violette died when she was nineteen and a half.

Her last years were a nightmare. She spent them in a climate of fear and pain. She never stopped trying to survive….

74 years later, her story has not been forgotten, and this may be my only opportunity to avenge her death.

At the same time, I have the feeling that I remembered her too late. I learned that time was very important because every time I discovered new information, I understood that the people who could have provided me with the missing pieces of the puzzle were no longer with us.

Violet had a life partner, Elie Benso, who gave his life in the name of his infinite love for her. I felt the need to find Elie’s family members and tell them what I had learned. With a great deal of effort and with the help of the exceptional people I met in the course of my research, I was able to find some of the members of Elie’s family.

They are scattered over several countries. They knew little of Elie’s history. I promised to show them the results of my research.

Violette has been a part of my life for a long time, with her beautiful face, her smile, her tenderness and softness. Recently, I had the chance to touch something that belonged to her: the lock of hair that she cut when she was in Drancy. It was given to me by the family of her father’s second wife. I find it very hard to explain what I felt when I held her in my hands.

When I found out that we shared the same date of birth, November 13, I realized that we had just closed a circle; a circle that had remained open all those years.

Roee Bar Siman Tov

October 2019

Jerusalem, Israel

Acknowledgements:

The Costi-Barembaum family: Renée, Martine, Lise and Sarah

Yvette Lévy

Sylvia Turpyn, daughter of Mathilde Jaffé

Georges Mayer, president of the Convoy 77 association.

Laurence Klejman, Holocaust historian and researcher

Shlomo Balsam, researcher at Yad Va’shem

Michael Ouaknine, Ashdod resident

—————————————————————————————————————————————————————–

ויולט בר סימן טוב

נובמבר13 1925 – אפריל 1945

הקדמה

ביולי 2017 התחלתי לערוך מחקר על קרוביי משפחתי שנספו בשואה.

.הוא התחיל בחיפוש אחר מידע שאספתי לקראת מסע לפולין, והפך למסע ששינה את חיי

סבי מצד אבי, ניסים בר סימן טוב, נולד בטיריה תורכיה ליעקוב ושרותה. לסבי היו שבעה אחים, אחד מהם הוא חיים (ויקטור) אשר בבגרותו נשא לאישה את שרה ולזוג נולדו שלוש בנות: ויולט, ג’נין ולואיז. כולן נספו בשואה והחלטתי שבמשפחה הזו אני רוצה להתמקד.

כבר בשלב הראשון של חיפוש אחר החומרים, צדה את עיניי תמונתה של הבת הבכורה ויולט:

יפה, אצילית וטובת לב, עדינה ובעלת מבט שובבי. מבלי לדעת להסביר, חשתי קרבה כלפיה. סיקרן אותי מאוד לנבור בחומרים ולחפש פרטים חדשים על חייה.

במסמך זה אציג את הממצאים מעבודת מחקר שביצעתי במהלך השנה האחרונה ושהתבססה על עדויות שמסרו בני משפחתה של ויולט ומכריה, על ראיונות שערכתי עם כמה נשים שהכירו אותה בזמן המלחמה, ועל מגוון מסמכי ארכיון.

בתקופת המחקר יצרתי קשר ונפגשתי בארץ עם משפחת ברמבאום הנפלאה מצרפת – רנה, מרטין קוסטי ובנותיה ליז ושרה (שרה מתגוררת בישראל). לאחר המלחמה חיים נישא בשנית לאישה בשם שרה שבעלה נרצח באושוויץ. בתה של שרה מנישואיה הראשונים, רנה, היא

אימה של מרטין.

הכרתי משפחה מדהימה שסייעה לי רבות בכתיבת המחקר, הן באמצעות גישור על פערי השפה והן באיסוף החומרים. ריגש אותי לראות כי על אף היעדר קשר דם, בנות משפחת ברמבאום היו מעורבות במחקר, היו סקרניות לגלות פרטים חדשים וחשו קרבה לויולט ולאחיותיה. ברגע זה הבנתי שמשפחתי התרחבה.

בני משפחת בר סימן טוב בצרפת

בשנת 1922 כשהיו בני 16 ו־18 סירבו חיים (ויקטור) בר סימן טוב ואחיו רפאל לשרת בצבא התורכי ומשום כך עלו בחשאי לאונייה שהגיעה לנמל מרסיי שבצרפת. שני האחים נישאו בפריז: לרפאל ולאסתר נולדו שתי בנות, ז’קלין וסולנז’, ולחיים ולשרה כאמור נולדו שלוש בנות, ויולט, ג’נין ולואיז.

אחיותיה של ויולט – ג’נין ולואיז

ויולט עם הוריה חיים ושרה

עם כיבוש צרפת ביוני 1940, נפלה פריז בידי הכוחות הגרמנים. שנתיים לאחר מכן ביולי 1942 נעצרו יותר מ־12,000 יהודים ובהם רפאל שהועבר למחנה הריכוז דראנסי (Drancy).

ב־23 בספטמבר 1942 נשלח רפאל לאושוויץ בשילוח מספר 36, שם קיבל את מספר האסיר 65484. ב-1 בפברואר 1945 רפאל הועבר למחנה עבודה מיטלבאו-דורה שבגרמניה ושרד את המחנה (עבד בקומנדו “דקס”) אולם למרבה הצער, בעת שחרור המחנה בידי הצבאות הרוסים והאמריקאים בינואר 1945, מת מאכילת יתר כמו רבים אחרים ונקבר ככל הנראה בקבר אחים במחנה. אשתו ושתי בנותיו שרדו את המלחמה.

חיים (ויקטור) נעצר ב־5 באוקטובר 1943 ונשלח למחנה האסירים בגרמניה סטאלג (Stalag). במיון שנעשה בידי הנאצים, שיקר כשהשיב בשלילה לשאלה האם יש לו בת זוג יהודייה, ועל כן נשלח למחנה עבודה באי אוריגני (Aurigny) הנמצא בצפון התעלה שבין צרפת לאנגלייה. במחנה לא היו תאי גזים ורוכזו בו שבויים שעבדו בעבודות כפייה כגון בניית ביצורים.

במחנה זה חיים (ויקטור) יצר נעליים מעץ. הוא שרד והצליח לברוח לאחר שהכין נעליים לאשת קצין המחנה. כאשר חיים חזר לדירתו ברחוב אמנדיר 14, הדירה הייתה ריקה.

אשתו שרה ושתי בנותיו, ג’נין בת העשר ולואיז בת השמונה, נעצרו ב־7 במארס 1944 ונשלחו לאושוויץ בשילוח 69. כעבור חמישה ימים נרצחו שתי הבנות בתאי הגזים ובספטמבר 1944 נרצחה שרה. ויולט לא הייתה בבית בעת מעצר בנות המשפחה.

חיים (ויקטור) בר סימן טוב

ויולט

בתם הבכורה של חיים ושרה, ויולט, נולדה ב־13 בנובמבר 1925 בפריז.

בכל דרך אפשרית ניסיתי לדלות פרטים על חייה. כשפגשתי את רנה, בתו החורגת של חיים, שאלתי אותה האם חיים סיפר לה על בנותיו. חיים, כמו עוד רבים אחרים, סירב עד יום מותו לספר על משפחתו בשל הכאב הגדול שבו היה שרוי. הוא נפטר בפריז בשנת 1972 ונקבר בישראל.

בראיון שקיימתי עם ניצולת השואה איווט לוי/דרייפוס (Yvette Lévy) אשר הכירה את ויולט בתקופת המלחמה, סיפרה איווט שויולט הייתה נערה חמודה ועדינה בעלת שיער בלונדיני ואף סולד. וכפי שהיא אמרה לי בעצמה:”When we speak about Violette, the ones who remember her keep a very fond memory of this good-looking young woman”. מעדויות אחרות נמסר לי כי ויולט עסקה בעיבוד עורות של עיזים כדי לתמוך באימה ובשתי אחיותיה ולפרנס אותן לאחר שאביה נאסר.

בערב שבו פגשתי את משפחת ברמבאום, נמסר לי פרט אשר תיאר יותר מכול את אישיותה המיוחדת של ויולט. ליז ברמבאום סיפרה לי שכאשר איווט לוי וניצולת השואה מטילדה ג’פה (Mathilde Jaffe) סיפרו לה בפריז פרטים על עברן בתקופת המלחמה, הן ברגע אחד עצרו ואמרו לה שעכשיו הן מעוניינות לספר על ויולט. כאילו בחרו לייחד ולהבדיל אותה מהאחרות. כשהתכתבתי עם סילבי טורפין (Sylvie Turpyn), בתה של מטילדה ג’פה (נפטרה בפריז בשנת 2019) היא סיפרה לי שאימה אהבה מאוד את ויולט.

כאמור, ויולט נעדרה מביתה ביום שבו אימה ואחיותיה נעצרו. בגיל 19 היא נותרה לבד בלי משפחה, ועל כן החליטה לעבור לגור בבית הילדים ברחוב ווקלין 9 rue Vauquelin)) בפריז שבו התגוררו נערים ונערות יהודיים שנותרו ללא משפחה. הבית הופעל מטעם הארגון הצרפתי יהודי אוז’י”ף UGIF על פי הסכם שנחתם בין UGIF לבין ממשל וישי והנאצים.

בבית UGIF נפגשו לראשונה ויולט ואיווט לוי. איווט הייתה בת 18 כאשר צרפת נכבשה בידי הנאצים. היא הייתה מורה בצופים, ושמרה על היתומים היהודיים ששהו בבית ברחוב ווקלין 9. איווט סיפרה לי במהלך הראיון שהיא וויולט עלו על אותה רכבת לאושוויץ ובבירקנאו עברו כמה סלקציות ביחד. עוד סיפרה איווט כי ויולט מעולם לא דיברה על אביה ועל המעצר שלו, אלא רק על אימה ועל שתי אחיותיה.

ויולט נעצרה בלילה שבין 21 ל־22 ביולי 1944 בעת פשיטה שערכו הנאצים על בית UGIF. בעת שהותה בדראנסי, ויולט גזרה צמה משערה וביקשה מחברתה למסור אותה לאביה אם יחזור הביתה בחיים. אחרי המלחמה קיבל חיים את צמתה של בתו, אולם הוא מעולם לא הרחיב על הנושא ואף לא דיבר על זהות החברה.

בזמן המלחמה ויולט התארסה לבחור יהודי בשם אלי בנסו שנולד ב־16 באפריל 1925.

איווט לוי סיפרה לי כי אלי היה בחור מרשים, יפה תואר ובעל שיער חום ואופי חם. נוסף על כך סיפרה איווט כי השניים היו מאוהבים ושאלי היה “מאוד מאוד נחמד אליה”. כשנודע לאלי שויולט תישלח למחנה השמדה, הוא לא היה מוכן להיפרד ממנה והתעקש להסגיר את עצמו כדי להישלח עמה לאושוויץ. מפקד המחנה בדראנסי שלח את אלי פעמיים לביתו אולם לאחר שאלי התעקש, הוא הכניס אותו למחנה ובכך למעשה נחרץ גורלו. אלי גורש עם ויולט לאושוויץ ומייד עם הגעתו ב־3 באוגוסט 1944, נשלח להשמדה בתאי הגזים.

ויולט בר סימן טוב ואלי בנסו

כרטיסה של ויולט במחנה דראנסי

הגירוש מצרפת

השלב השלישי של גירוש היהודים מצרפת החל ביולי 1943 ונמשך עד אוגוסט 1944 תחת פיקודו של אלויס ברונר (עוזרו של אדולף אייכמן, ראש המחלקה לענייני היהודים ולענייני פינוי).

ברונר פיקד על מחנה דראנסי שבו רוכזו כל היהודים שיועדו לשילוח. במשך 13 חודשים נשלחו 21 שילוחים מצרפת לאושוויץ (מספרי השילוחים 57–77) ובהם כעשרים אלף יהודים, הן ילידי צרפת הן נתינים זרים. גירוש היהודים מפריז נמשך למרות התקדמותם של כוחות בעלות הברית אל העיר. עד סוף יולי איבדו הגרמנים את השליטה בצפון מערב צרפת, ובעלות הברית עמדו לכבוש את העיר לה מאן (Le Mans) השוכנת כמאתיים קילומטרים מפריז.

ויולט כאמור נעצרה בבית UGIF בלילה שבין 21 ל־22 ביולי 1944, וב־31 ביולי 1944 גורשה עם ארוסה אלי בנסו בגירוש ההמוני האחרון מדראנסי – CONVOI 77. בזמן זה האמריקאים היו במרחק של 150 – 200 קילומטרים מפריז, וכחודש ימים לאחר מכן שוחררה פריז מידי הגרמנים ע”י צבא צרפת ודיביזיה אמריקאית.

בשילוח 77 גורשו כ־1,310 יהודים בקרונות בקר, וכ־800 מתוכם נרצחו בתאי הגזים מייד עם הגיעם לאושוויץ. בשילוח היו יותר משלוש מאות ילדים שנחטפו מבתי יתומים ברחבי פריז, ילדים שנאלצו להתמודד עם נסיעה בלתי נסבלת, עם בכי בלתי פוסק, עם פחד ועם סבל מחום ומצמא. בעדות שמסרה איווט לוי, היא סיפרה על שוטרים לבושי מדים שהכניסו בכוח את הילדות הלבושות פיג’מות למשאית שהמתינה לקחת אותן לדראנסי. ביום חם מאוד הועלו המגורשים לקרונות שבכל אחד מהם הצטופפו כשישים איש. לדברי איווט, “היה צפוף כל כך עד שהמגורשים נדחקו זה אל זה כמו סרדינים. היה להם רק דלי מים אחד ודלי ריק אחד לעשיית הצרכים”.

בעדותה הכתובה של איווט ניכר כי היא בחרה להזכיר דווקא את ויולט שנסעה עימה באותו קרון בדרך לאושוויץ. איווט סיפרה כי על אף שנולדה בפריז, ויולט לא ענדה טלאי צהוב כי “הייתה אזרחית טורקייה”. נוסף על כך, סיפרה לי איווט כי ארוסה של ויולט אלי בנסו שישב עימן בקרון הרכבת בדרך לאושוויץ, שר לויולט את שיר האהבה הספרדי “לה פלומה” (La Paloma) בניסיון להנעים את רגעיה האחרונים לפני ההגעה לאושוויץ. לאחר שסיימתי לקרוא את עדותה הכתובה של איווט לוי, זו הייתה הפעם הראשונה שבה הצלחתי לדמיין את עצמי יושב בקרון עם ויולט וחולק עימה את רגעי הפחד.

הרכבת שבה נלקחה ויולט הגיעה לאושוויץ־בירקנאו ב־3 באוגוסט 1944, כחודש לפני שאנה פרנק הגיעה לאושוויץ עם משפחתה. לאחר מכן השתיים שהו יחד כמה חודשים בברגן בלזן, וכידוע אנה פרנק נפטרה כמה חודשים לפני שחרור המחנה. בעדותה כתבה איווט ש”אי אפשר לשכוח את ההגעה לאושוויץ. הלילה, הזרקורים, האנשים במדי האסירים המפוספסים, הצרחות של חיילי הס”ס ונביחות הכלבים”.

אושוויץ והמעבר לברגן בלזן

מייד עם הגעתה של ויולט לאושוויץ, נערכה סלקציה והגרמנים בחרו לשלוח לעבודה בבירקנאו מעל מאה נשים. האסירות שהיו במצב “סביר” נשלחו לצעדת המוות למחנה מטאהאוזן שבאוסטריה. מטילדה ג’פה סיפרה שויולט הייתה בהריון כאשר היא הגיעה למחנה ההשמדה אושוויץ. ב־27 באוקטובר 1944 ערך מנגלה המרצח עוד אחת מהסלקציות שלו, וכאשר הבחין בבטנה ההריונית של ויולט, הוא הפך אותה לעוד קורבן של הניסויים שערך באושוויץ. על תוכן הניסוי המצמרר שעברה ויולט היא סיפרה למטילדה כמה חודשים לאחר מכן כאשר השתיים נפגשו בברגן בלזן.

על פי עדותה של איווט לוי, אחת מהבנות, בלימה (ברטה) קראוז (Blima Krauze), מצאה במחנה את אביה, מר פוליש, שהיה קאפו באושוויץ. אביה רצה להעביר את בתו למקום בטוח יותר אולם הבת מיאנה לעזוב לבד. איווט לוי סיפרה שקבוצת הבנות רצו להישאר ביחד ועל כן אף אחת לא התנדבה לעזוב. בשלב כלשהו אחת הבנות הציעה שויולט תתלווה אל בלימה לברגן בלזן, וויולט הסכימה. לברגן בלזן הובאו נשים מאושוויץ בין 23 באוגוסט 1944 לתחילת פברואר 1945. נשים אלו עבדו בעיקר במפעלים ששימשו את הגרמנים לתעשיית המלחמה, כמו מפעלי מטוסים ותחמושת, ולמעשה החליפו את הגברים הגרמנים שיצאו למלחמה.

בנובמבר 1944 רוחות החורף הכבדות שברו את האוהלים והנשים הועברו לבית החולים שבו שהו חלק משבויי המחנה. הן שוכנו בבקתות עץ אך במבנים רבים לא היו מיטות ובמקרים מסוימים אפילו לא רצפה. באותה תקופה קדחת הטיפוס ומחלות אחרות השתוללו בכל המחנות.

כאשר מטילדה ג’פה הגיעה לברגן בלזן ב־4 בינואר 1945, היא פגשה שם את ויולט שסיפרה לה שבזמן שהותה באושוויץ, מנגלה פתח את בטנה והשתיל בה עובר של חתול.

מטילדה סירבה למסור בעדותה את דבר הניסויים על ויולט, היא סיפרה על כך רק לבתה אשר הסכימה לספר לי את הסיפור רק לאחר כמה פעמים ששוחחתי איתה. בעדותה ציינה מטילדה “I cannot say it ,because I’m afraid to believe it”.

מרגע זה פתחתי במאמצים לאתר את בלימה קראוז (שנודעה בתחילה כברטה קראוז) כדי לקבל ממנה עוד פרטים על ויולט: בחיפוש שערכה ברשימות הניצולים, גילתה מרטין קוסטי כי שמה הוא בלימה קראוז; ובחיפוש שערכתי באינטרנט מצאתי אזכור בודד לכינוס משנת 2015 שבו אחד הדוברים סיפר על זיכרונותיה של אשתו המנוחה בלימה מתקופת השואה. כשפניתי לארגון בארצות הברית שאירגן את הכינוס, נמסר לי כי בלימה שרדה את השואה והתגוררה בארצות הברית עד מותה בשנת 2011. בכך נגוזה עוד הזדמנות לשוחח עם אישה שחלקה עם ויולט את ימיה האחרונים.

נותרה עדיין השאלה הגדולה מה עלה בגורלה של ויולט, מתי היא נפטרה ומה היו נסיבות מותה.

בניסיון לענות על שאלות אלו, יצרתי קשר עם המוזיאון בברגן בלזן. יש לציין כי מראש הציפיות שלי היו נמוכות מכיוון שידעתי שלפני שהגרמנים עזבו את המחנה, הם השמידו את כל החומרים שבהם תועדו האסירים. אך התשובה שקיבלתי השלימה לי חלק משמעותי בפאזל שאותו הרכבתי במסע.

לאחר שחרור מחנה ברגן בלזן ב־15 באפריל 1945, האסירים הצרפתים שהיו במצב בריאותי טוב יותר ערכו רשימה של כל האזרחים הצרפתים ששרדו. האסירים השלימו את הכנת הרשימה ב־19 באפריל 1945, ארבעה ימים לאחר השחרור. ברשימה זו מופיע שמה של ויולט פרסימנטו (בר סימן טוב) אשר שרדה את התלאות תחת ידיהם של הצוררים הנאצים.

עוד נודע לי כי בסוף אפריל האסירים ערכו עוד רשימה של השורדים, ושם למרבה הצער שמה של ויולט כבר לא הופיע.

מכאן ניתן להסיק כמעט בוודאות כי ויולט שרדה את המלחמה, אולם המחלות הקשות שפשטו במחנה הכניעו את גופה שלא יכל עוד.

באשר למועד פטירתה של ויולט ישנן שתי אפשרויות: האחת היא שויולט נפטרה במחנה הריכוז לפני שהעבירו אותה לבית החולים שהיה כמה קילומטרים מהמחנה, והשנייה היא שויולט עברה לבית החולים אך נפטרה שם כעבור זמן קצר.

מהמוזיאון בברגן בלזן נמסר לי כי על פי האפשרות הראשונה, ויולט אמורה להיות קבורה באחד מקברי האחים במחנה הריכוז שעל שרידיו נבנה אתר ההנצחה של ברגן בלזן, וכי על פי האפשרות השנייה ויולט אמורה להיות קבורה בשורה הראשונה של בית קברות קטן בסמוך לצריף צבאי שעדיין נמצא סמוך למחנה. צריף זה שימש מחנה עקורים עד 1950 ולאחר מכן מחנה בריטי עד 2016. מאז הוא נמצא תחת פיקוח צבאי גרמני על ידי נאט”ו.

מכאן אפשר לשער כי ויולט נפטרה בין 19 ל־30 באפריל 1945

| רשימת השורדים 19 אפריל 1945 |

שמות האנשים שלא מופיעים בספירה השניה – סוף אפריל 1945 תעודת פטירה של ויולט

תעודת פטירה של ויולט

ויולט סיימה את חייה הקצרים בגיל 19 וחצי.

סוף דבר

ויולט סיימה את חייה הקצרים בגיל 19 וחצי

שנותיה האחרונות היו כמו חלום בלהות, והיא חיה במציאות של פחד, כאב, מורא גדול וניסיון הישרדות בלתי פוסק.

אחרי 74 שנים סיפורה לא נשכח, וזו אולי הנקמה היחידה שאני יכול להביא בשמה.

עם זאת אני מרגיש שנזכרתי מאוחר מדי. למדתי שלזמן יש משמעות אדירה כי ככל שגיליתי פרטים חדשים במחקר, הבנתי כי האנשים שיכולים להשלים לי את חלקי הפאזל בסיפור חייה של ויולט, כבר לא איתנו.

לויולט היה שותף לחיים, אלי בנסו, שמסר את חייו בשם אהבה ללא גבולות.

גמלה בלבי ההחלטה כי אני חייב למצוא את משפחתו ולספר לה את הפרטים הידועים לי. לאחר מאמצים רבים ובסיועם של אנשים מדהימים שפגשתי באמצע הדרך, הגעתי לבני המשפחה של אלי המפוזרים בכמה מדינות בעולם. הם לא ידעו יותר מדי פרטים אז הבטחתי לשתף אותם בממצאי המחקר.

תקופה ארוכה ויולט מלווה אותי עם פניה היפות, חיוכה הקטן שמשוך על פניה, הרוך והעדינות. לאחרונה זכיתי לגעת במשהו מוחשי ממנה: צמת השיער שויולט גזרה מראשה במחנה דראנסי, הועברה לרשותי באמצעות משפחת אביה בפריז. קשה להסביר את ההתרגשות שאחזה בי באותו רגע.

כשגיליתי שתאריכי הלידה שלנו מצטלבים זה בזה – 13 בנובמבר – הרגשתי שנסגר לו מעגל ארוך שנים.

רועי בר סימן טוב

אוקטובר 2019

ירושלים, ישראל

תודות:

משפחת ברמבאום קוסטי – רנה, מרטין, ליז ושרה

איווט לוי (Yvette Lévy)

סילבי טורפין (Sylvie Turpyn), בתה של מטילדה ג’פה (Mathilde Jaffe)

ג’ורג’ מאייר (Georges Mayer), נשיא עמותת 77 CONVOI

לורנס קליימן (Laurence Klejman), היסטוריונית וחוקרת שואה

שלמה בלסם (Shlomo Balsam), חוקר ב”יד ושם”

מיכל ועקנין, תושבת אשדוד ישראל, סייעה רבות באיתור משפחתו של אלי בנסו

Français

Français Polski

Polski

Roy, J’ai relu une fois de plus ton histoire bouleversante sur Violette et je voulais te dire combien je suis bouleversée par cette vie brisée mais surtout par ta détermination à donner à Violette toute la dignité qu’elle mérite. Personnellement je connais l’horreur de son histoire d’amour depuis mes 13 ans, j’en ai 65 ! maman (Mathilde Jaffé) m’a toujours parlé du fiancé mort par amour et … du chat … c’est pourtant si difficile à croire! Violette a toujours vécu dans le cœur de maman, et elle a toujours été pour moi l’image de la mémoire, Violette est un visage, une douceur, une page complète de l’histoire de ma mère. Après avoir lu le récit poignant de sa vie, je tiens à te dire à quel point je me sens proche de toi par l’émotion, par le sentiment que nous portons à nos disparus, nôtre âme persécutée trouve un chemin jusqu’à eux, ils sont notre horrible vérité dont nous sommes les porteurs de respect et de mémoire : voilà leur sépulture ! Violette a probablement guidé tes recherches, ses cheveux entre tes mains, vos dates de naissance identiques n’en sont-elles pas la preuve?! Je te souhaite maintenant de vivre en paix avec l’Histoire même si je sais que ce ne sera jamais possible vraiment! que cette année 2020 t’apporte le meilleur. mille tendresses de ma part. (Mathilde, ma maman a perdu la tête et a tout oublié … mais elle va bien, juste sa mémoire est partie peut-être retrouver sa sœur Esther morte à Bergen-belsen à 17 ans et …. Violette! Qui peut savoir ?… ) Sylvie ❤

Sylvie,

Thank you very much for your comment. I appreciate it very much.

Your mom and you were part of my research.

I’m very happy that I met you so you could tell me things from Violette’s life.

It’s an obligation for us to tell and remember the story of those who were murdered in the Holocaust.

I hope you and your mom are well. All the best for the future.

Thank you very much

Roy Bar Siman Tov

Israel