Léon BRASCHEVIZKY

Introduction to the project

Over the course of the 2023-2024 school year, we focused on the story of Léon Braschevizky, who was lucky enough to survive Auschwitz and return to France, and whose life was so eventful. We therefore wanted to pay him a special tribute when we went to Auschwitz in partnership with the Shoah Memorial on November 30, 2023.

We were fortunate enough to be able to meet one of Léon’s nephews and speak with his niece, which enabled us to get to know him a little better. Léon’ spirit has remained with us throughout our final year in high school, as we set out to breathe new life into the stories of some of the Convoy 77 deportees.

Léon himself proved to be a great help to us, as he left behind a wealth of written material in which he recounted his life story and experiences. His nephew, François Guichard, gave us a glimpse of what he was like in real life. We soon realized that Léon was a miraculous figure who had escaped death time and again and had seemingly lived a thousand lives. This is why we decided to create a display board about him when we got back from our study day in Birkenau.

Léon Braschevizky: “a miracle of a man who lived a thousand lives”

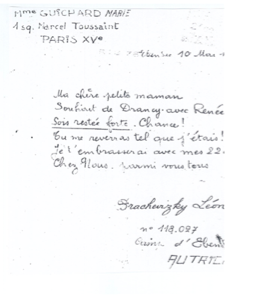

Note

Before we come to the biography, we need to explain the spelling of the family name Braschevizky. We noticed that the Léon and his family’s surname was not always spelled the same way, either in the records provided by the Convoy 77 team, or in those we found during our research at the Shoah Memorial. In fact, on the Wall of Names[1] at the Shoah Memorial, it is spelled Braschevizki.

In the records from the French Defense Historical Service in Caen (BRASCHEVIZKY Léon, ref. 21 P 660 121) there is a letter from Léon himself, addressed to the Ministry of Veterans’ affairs, in which he requests that they correct[2] the spelling of his surname.

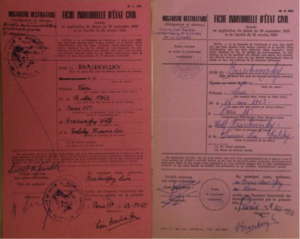

Léon Braschevizky’s letter to the Ministry of Veterans’ affairs, dated 1958.

The civil status form that confirms the correct spelling of Léon surname as Braschevizky

Biography

Léon’s parents were Léa Talsky, who was born on October 17, 1897 in Makarov in Russia and Wolf Braschevizky, who was born in 1888 in Jerusalem, now in Israel. The couple lived in Paris and worked in the tailoring trade.

They had four children:

- Marie, who was born in the 12th district of Paris on August 18, 1919

- Renée, who was born in the 12th district of Paris on July 24, 1921

- Léon, who was born in the 11th district of Paris on May 16, 1923

- Jacques, who was born in the 20th district of Paris on April 6, 1926

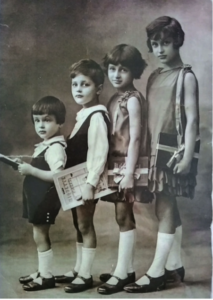

The siblings in the 1930s, Jacques, Léon, Renée and Marie

on prizegiving day. Source: private collection

Marie married Albert Guichard in 1938. He was soon to become a prisoner of war.

Renée started dating Maurice Laval, a Trotskyist resistance fighter[3], who she met at the Youth Hostel group [4] in 1940. They got married on May 23, 1942 in the 14th district of Paris.

They moved to Montrouge, in the suburbs south of Paris, where they were active in the Resistance movement.

Photo of Renée and Maurice in the 1940s. Source: private collection

As for Léon, he lived with the parents and his youngest brother, Jacques, at 2 rue Wilfrid Laurier in the 14th district of Paris. He was a graphic designer/illustrator.

The French police arrested Léon’s father, Wolf Braschevizky,[5] on December 12, 1941 on grounds that he was « Israelite », meaning Jewish. He was interned in the Royallieu camp near Compiègne[6], in the Oise department of France, which was also known by its German name, Frontstalag 122. He was released, together with some other sick men, on March 13, 1942 because he was thought to be dying, but in fact he survived and only died some years later, in 1955.

The arrest

On March 11, 1944, not having heard from his sister Renée and brother-in-law Maurice, Léon went to look for them at their home at 103 avenue Verdun in Montrouge. As soon as he arrived, the French police stopped him. They had set a trap for him, having arrested Renée and Maurice the previous day. Léon, who was using forged identity papers, was arrested and taken to the detention center.

When Léon did not return home as expected, Jacques, his 18-year-old younger brother, also went to Montrouge, where he too was arrested. He was then interrogated, beaten and detained for a few days before being released[7].

As for Léon, he was imprisoned in the Conciergerie from March 2 to April 6, 1944, then at the Prison de la Santé from April 6 to May 19, 1944, and lastly in Fresnes jail from May 19 to July 14, 1944. He was then interned in Drancy from July 14 to July 31, 1944, where he met up with his sister Renée, who had been transferred there from the Petite Roquette prison.

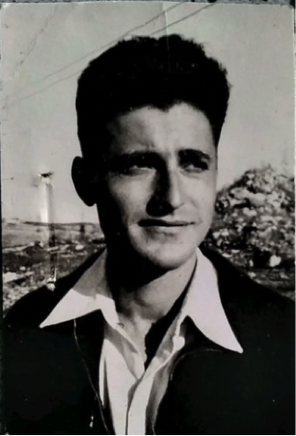

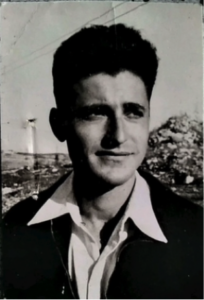

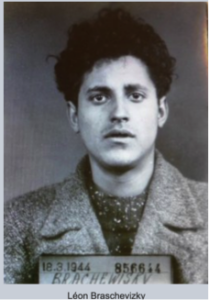

Photo of Léon. Source: Paris prefecture

Both brother and sister were deported to Auschwitz on Convoy 77 on July 31, 44[8].

The hell of the concentration camp

The journey to Auschwitz-Birkenau

The first time Léon avoided certain death was when he got on the train to Auschwitz. Léon Bloch, a retired colonel, persuaded him not to get into the same car as Alfred Stark, who was born in Paris on March 19, 1914 and died in Auschwitz on August 5, 1944. He was thus spared the tragic fate of a car full of deportees who were all Resistance fighters and who were murdered in the gas chambers as soon as they arrived in Birkenau[9].

Although they were rather puny, Léon and his sister Renée were both selected to go into the camp to work. Léon had the number B 3701 tattooed on his left forearm, a tattoo that he kept for the rest of his life. This was the first time that he felt humiliated and powerless. He later described being tattooed like “a steer or a sheep, bound for the slaughterhouse”.

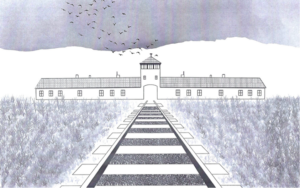

Drawing of Auschwitz by 12th grade student Andréa Barros,

Léon was initially assigned to earthmoving work and was then transferred to the bomben kommando, where he was tasked with removing unexploded bombs[10] at the oil refinery, match factory and railway station in Czechowice (Tschechowitz in German), a town some 25 miles from Auschwitz, which he later described as “a haven of peace in the eye of the storm”.

Léon and his colleagues changed worksites every day, as trails of unexploded bombs were scattered across the countryside around the Vacuum Oil Company SA site, which had been razed to the ground[11]

He later wrote that he and his fellow internees had to learn a German marching song, D’blauen Dragoner, [12].

On October 1st, Léon escaped death again during another selection. Sadly, a fellow deportee, Benjamin Fondane, was not so lucky[13].

In October 1944, the SS were on the lookout for draughtsmen, painters, photographers, photoengravers and printers. Léon introduced himself as a draughtsman and “opticien de precision” (meaning detailed artistic work on glass or porcelain), even though he had little specialist knowledge in this field[14]. He later explained in his notebooks that he had to pass a drawing test, and that the SS lieutenant in charge was quite lenient with him.

Together with six or seven other men, he was transferred to Sachsenhausen.

However, on November 1, 1944, not long before he left Auschwitz, he witnessed an unusual, but hopeful incident. The men were working on a construction site in Auschwitz when the first snow of the winter began to fall. An SS dispatch rider on a motorcycle told them to go back to their blocks. “As we were waiting idly the barracks, a faint Hatikvah[15] broke out, and gradually grew louder”, he wrote.

Sachsenhausen[16]

On November 11, 1944, Léon Braschevizky was transferred by train from Auschwitz to Orianeburg-Sachsenhausen. When he arrived on November 18, he was put in quarantine.

On January 23, 1945, Léon Braschevizky was put in block 19, given the number 132, and assigned to the counterfeit money kommando[17].

His work involved printing counterfeit banknotes from then until March, when the Kommando had to dismantle the machines and were sent, together with all the printing equipment, to Mauthausen. The Germans’ plan to print counterfeit banknotes proved unsuccessful.

The train journey from Sachsenhausen to Mauthausen took from March 11 to March 15, 1945.

Mauthausen[18]

When he arrived at Mauthausen, Léon was given the number 138407. He stayed there from March 15 through April 15, 1945, during which time he did some installation work.

In April, after spending the month in Mauthausen, he was transferred by truck to Shlier[19], a small camp with only four barrack huts, where again he did some installation work.

Léon later recalled a snowy morning in late April, and how he noticed that the flags were flying at half-mast: Hitler had committed suicide[20]!

A telegraph arrived from Berlin, saying that send the counterfeiting kommando were to be sent back to Mauthausen. According to Léon, the Nazis had been ordered to kill them all, but some Austrian resistance fighters seized the opportunity to slash the tires of the cars that should have taken them to their deaths.

In the end, they were put on trucks and taken to Ebensee (in the Tyrol). Léon avoided death yet again, not only when his kommando was supposed to be eliminated, but also because he did not have to go on the death march, while the majority of the deportees did.

Ebensee[21]

In Ebensee, he witnessed the SS destroy the prisoners’ files and photographs.

The camp was liberated on May 6, 1945.

On May 10, he wrote to his mother, telling her that he was still alive and would be home soon.

Léon’s letter to his mother, dated May 10, 1945. Source: private collection.

Repatriation to France

On May 18, 1945, the American troops took Léon and the other deportees by truck to Nuremberg, where he spent his last night in Germany.

Léon arrived at the Hotel Lutetia[22] in Paris on the same day as his sister, Renée. Their younger brother, Jacques, was there to meet them. Jacques and their sister Marie had been going to the hotel every day to see if their siblings had arrived, or if there was any news of them.

Léon was worried about the work he had done with the counterfeiters’ kommando in Block 19.

After the war

Léon stayed in Paris for 5 years, after which he decided to make Aliyah (return to the Land of Israel).

Léon with François, his sister Marie’s son, in 1946. Source: private collection

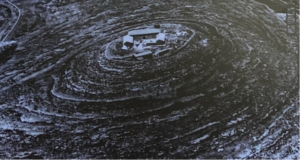

While in Israel, Léon helped set up the Franco-Belgian kibbutz, Nevé Ilan, in the Judean Mountains, some six miles from Jerusalem. The kibbutz expanded rapidly and did well financially as it introduced poultry and dairy farms and began growing mushrooms. However, from the 1950s onwards, relations between the members became increasingly strained, and the kibbutz was eventually abandoned in 1956.

Photo of the Nevé Ilan kibbutz, taken in 1950. Source: Shoah Memorial.

Léon always spoke of Nevé Ilan as a place that attracted a number of French and Belgian intellectual types who had little or no previous farming experience.

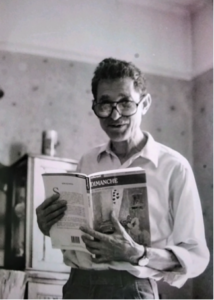

Léon in Israel, between 1950 and 1955 Source: private collection

When his father died in 1955, Léon moved back to France to live with his mother. He worked as an illustrator and graphic designer.

Léon in France. Source: private collection

On April 25, 1958, he applied for the status of “political deportee” (meaning that he had been deported on political grounds), which he was granted on November 9, 1958.

LEON BRASCHEVIZKI

© French Defense Historical Service in Caen, ref. 21 P 660 121

The Braschevizky siblings in Luxembourg in October 1996

Jacques, Léon, Renée and Marie. Source: private collection.

Léon died in Paris on January 15, 2017.

To you who survived

Your face bears all the sadness

Of your soul and others’ souls, bruised and in distress

Scarred by this hell, the source of your weaknesses

Condemned to perish in this fortress

That harbors within in it a terrible memory

That you’d like to be rid of.

And yet, it must not be allowed to define you,

To soil you, erase you, break you or harm you.

To confront this terror

Do not repeat these horrors,

All buried deep in your heart,

The cause of your pain.

You have to be able to remember

To remind yourself of the past.

We did not do enough.

They must not forget.

Because in the end,

No bandage

Is strong enough.

You had a man’s face, quite simply.*

* this is the last line of the poem “Préface en prose” by Benjamin Fondane, one of Léon’s fellow prisoners, who was murdered in Auschwitz. The poem was read out at Léon’s funeral.

Léon’s name is inscribed on the Wall of Names at the Shoah Memorial in Paris, but his surname is spelled wrongly.

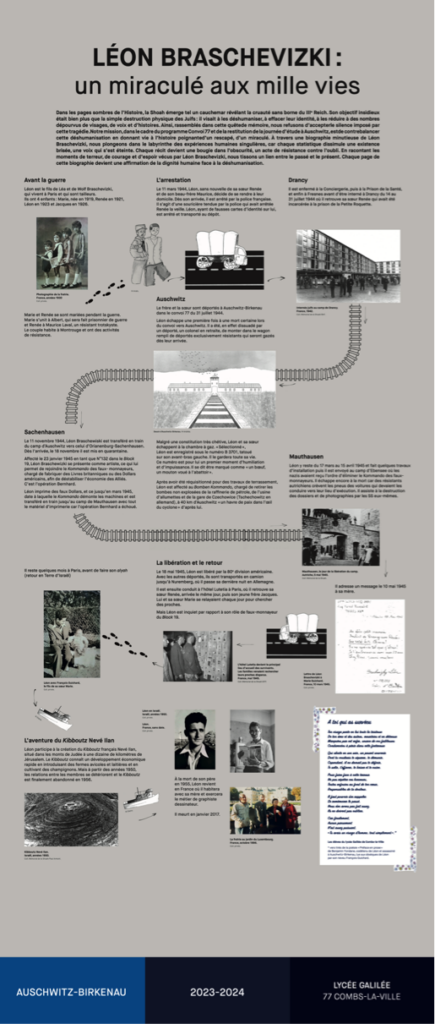

The introduction on the information panel about Léon Braschevizky, which the students made for Ile de France regional authorities

Among the dark chapters of history, the Holocaust unfolds like a nightmare, revealing the unbridled cruelty of the Third Reich.

The Nazis’ underlying objective was far more than just the physical destruction of the Jews: it was to dehumanize them, to erase their very identities, to reduce them to numbers without a face, a voice or a history.

And so, united in our collective endeavor to remember, we are determined not to allow this tragedy to be silenced. Our duty, as part of the Convoy 77 project and in writing about our study day in Auschwitz, is to redress this dehumanization by breathing life into the poignant story of a survivor, a “miracle” man.

In writing this painstaking biography of Léon Braschevizky, we delve into the labyrinth of unique human experiences, as behind every statistic lies a shattered existence, a voice that has been silenced. Each story becomes a candle in the darkness, an act of resistance against oblivion. By recounting the terror, courage and hope that Leon Braschevizky experienced, we are forging a link between the past and the present.

Each and every page of this biography proves that human dignity can prevail, even in the face of dehumanization.

Orianne Multon, 12th grade student

The information board that the students made after their study trip to Auschwitz

Notes and references

[1] The Wall of Names of all the Jewish people deported from France is in front of the Shoah Memorial, which is in the 4th district of Paris.

[2] LEON BRASCHEVIZKI © French Defense Historical Service in Caen, ref. 21 P 660 121

[3] Trotskyism is a Marxist political philosophy based on Leon Trotsky’s writing, activism and ideas. From 1924 onwards, Trotskyist ideology was mainly characterized by its opposition to the Stalinist vision of communism, challenging the reign of bureaucracy and advocating democracy and freedom of debate within the Communist Party.

[4] On August 28, 1930, Marc Sangnier opened the first youth hostel in France and founded the French League for Youth Hostels (L.F.A.J.). Youth Hostels offer affordable year-round accommodation, sports and cultural activities and provide an opportunity for young people from different countries to meet while respecting each other’s differences and opinions, thereby contributing to the development of peace and brotherhood between peoples.

[5] Léon Braschevizky’s testimony

[6] This was the “Round-up of the Notables”, which took place in Paris on December 12, 1941. It was the third major roundup of Jews carried out by the German authorities in France, with the complicity of the Vichy government, since the start of the Occupation during the Second World War. The rounded-up prisoners were sent to the Royallieu camp in Compiègne. This became a Nazi transit camp, which was in operation from June 1941 to August 1944. It was the second largest internment camp in France during the Occupation, after Drancy.

[7] Léon Braschevizky’s testimony

[8] Convoy 77 was the last large convoy to leave Drancy for Auschwitz. Aboard the train were more than 1,300 deportees: 726 of whom were murdered in the gas chambers as soon as they arrived, while 291 men and 183 women were selected for work; only 93 men and 157 women from the convoy survived the hell of the camps until 1945.

[9] There were many resistance fighters in the same car as Stark, and at one point, when the train stopped, the Germans made them strip naked and took away their food and water. They continued the journey like that until they arrived in Birkenau, where they were loaded onto a truck and taken straight to the gas chambers.

[10] As the war drew to a close and the Allies intensified the bombing of German munitions facilities, Auschwitz prisoners were increasingly used to carry out bomb disposal, mine clearance and repair work on damaged buildings and factories.

[11] The Vacuum Oil Company was an oil refinery that was bombed. There was extensive damage, and 70-90% of it was destroyed. Many of the bombs failed to explode, many of them left in the wasteland surrounding the works. Source: Projet de l’association Tiergartenstrasse 4 : retrouver les sous—camps d’Auschwitz.

[12] The song “Die blauen Dragoner” (the blue dragons), is a well-known German song.

[13] The poet Benjamin Fondane was murdered on October 3, 1944 in Auschwitz-Birkenau. Born in Jassy, Romania, in 1898, he was still a high school student when his first poems were published. He had a great fascination with France, moved there in 1923 and became a French citizen. A poet, critic and philosopher, he became well known in literary and intellectual circles. He was drafted into the French army, taken prisoner, escaped and returned to Paris. Despite the danger he was in because he was a Jew, he refused to leave his home. He was reported and then arrested on March 7, 1944, and taken to Drancy. From there he was deported to Auschwitz on May 30.

[14] Léon’s own words

[15] The Hatikvah is a song that became a symbol of resistance during the Holocaust. It is now the Israeli national anthem.

[16] The Sachsenhausen concentration camp was the largest Nazi camp in the Berlin area. It was located near Oranienburd, north of the capital.

[17] Léon was one of 144 Jewish inmates who were forced to work as counterfeiters in a special unit within the camp. He had to manufacture British pounds and/or American dollars. This was known as Operation Bernhard. The objective was to produce thousands of counterfeit British pound bills, in order to destabilize the British economy.

[18] The Mauthausen concentration camp was built around the village of Mauthausen in Upper Austria, about 14 miles from Linz.

[19] A sub-camp of the Mauthausen concentration camp, located at Redl-Zipf in Upper Austria.

[20] On April 30, 1945

[21] Ebensee camp in Austria was an annex camp of the main Mauthausen concentration camp.

[22] From April 26 toSeptember1, 1945, this hotel on the Left Bank of the Seine was used as a reception and transit center for prisoners who had just returned from the hell of the concentration camps.

Français

Français Polski

Polski