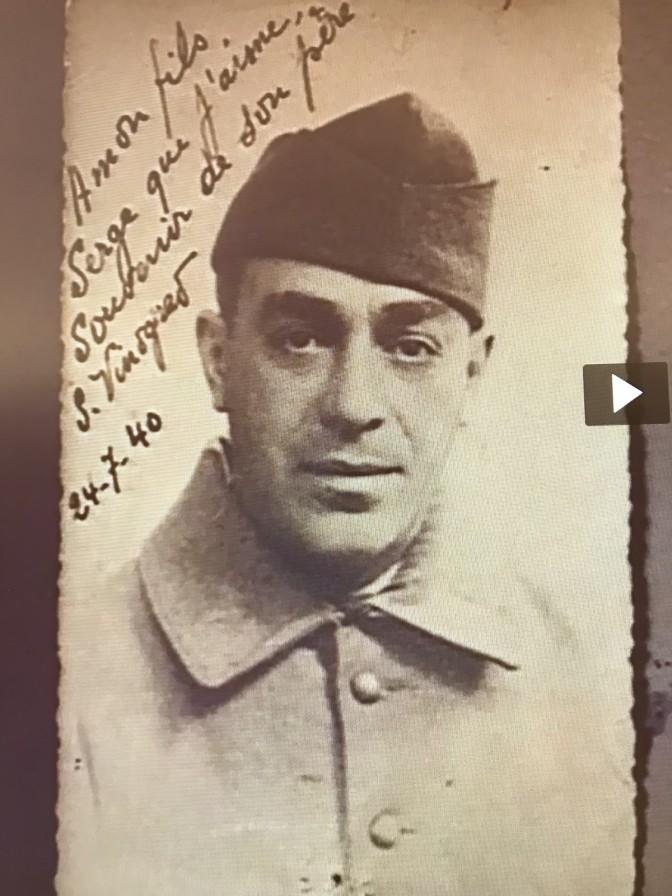

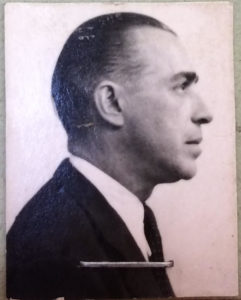

Samuel VINOGRAD

Born on December 24, 1894 in Wiazowna, Poland. Died in Poland in the winter of 1944-45.

This biography was initially written by Piotr Kisielewski and Pierre Alexandre Chauffour, 12th grade students at the French High School in Warsaw, Poland, with the guidance of their French and Polish teachers, Valerie Kuhn and Barbara Subko, during the 2018/2019 winter semester. After some new records came to light, Samuel’s son, Serge Vinograd, and historian Laurence Klejman updated the text in December 2024.

Samuel Vinograd had not yet turned 50 when he was arrested at his home at 11 rue Martel, in the 10th district of Paris, on July 3, 1944. His wife later stated that the French police came for one reason alone: because he was Jewish. The concierge and some neighbors in the building also testified to this. Samuel was indeed Jewish but he was also a French citizen, having been naturalized on November 11, 1926.

In fact, although he was born in a village called Wiazowna, near Warsaw, he had lived in France for most of his life.

BEFORE THE WAR

Growing up in the Marais neighborhood in Paris

Samuel was around 3 years old when his middle-class parents, Hersh (also known as Georges) and Faiga (Fanny) Bressler, left their home on rue Stawski in Warsaw [1]. They moved to Paris in around 1901 [2]. Samuel (who was named Szmul Joseph at birth) had three older sisters, Rose, Esther and Sarah, and a younger brother, Ber Haïm (born in Warsaw in 1898), who was renamed Bernard when he arrived in France.

The family lived in the Marais neighborhood, in the 4th district of Paris. In 1905, they were living at 13 rue des Rosiers [3]. It was in this working class Jewish neighborhood, known as the “Pletzl”, that Samuel grew up and went to school.

As a young boy, Samuel loved singing, and had a beautiful voice. His son recalls that he often used to sing in synagogue and at parties. Did he want to make a career out of it? It would seem so: on May 24 1917, when his father died and Samuel declared his death at the town hall in the 4th district of Paris, he described himself as a “vocal artist”. Was it his father’s death that changed things? As the eldest son, although he was only 22, he then had to support his mother and the rest of the family, so he became a cap-maker, like his father before him. His army service record confirms this.

Samuel’s marriage to Fleurette

When he married Blima (Fleurette) Wienerbett, on May 15, 1919, Samuel was still a cap-maker and was living at 3, rue du Trésor, in the heart of the Marais, with his mother and his sisters, Esther and Sarah. By that time, his other sister, Rose, had married Jacques (Jacob) Bresler, who was Samuel’s witness at the wedding. The religious ceremony was held at the Tournelles synagogue on the afternoon of May 18. Fleurette, who was born in Paris and was thus a French citizen, lost her French nationality and became a Polish citizen like her husband. She later became a French citizen again when Samuel was naturalized.

The young couple set up home at 20 rue des Tournelles, not far from the synagogue and the Place des Vosges. At that time, the neighborhood was not as chic as it is nowadays, and almost all Jewish migrants from Central and Eastern Europe made their way there at some point. It was there, in their apartment, that Fleurette gave birth to their first daughter, Balbine, named after her maternal grandmother, Baïla, who had adopted the French version of her name. Their second child, Serge, was born on July 24, 1929, also at home.

Haberdashery and fabrics

Although he still enjoyed singing, Samuel left behind his childhood dream of a career in music. He did not stay long in the cap-making trade either. In 1929, when Fleurette was pregnant with Serge, the couple went through a rough patch. They first ran a seafood stall outside a Parisian restaurant and then went into the haberdashery business together. They set up a market stall called “Fleurette” at the Village Suisse market on Avenue de Suffren, not far from the Eiffel Tower. Serge recalls that the family moved into an apartment somewhere near the Champ de Mars. This all happened in around 1930. The haberdashery business went bankrupt in 1932.

Was this when the family left central Paris and moved to Livry-Gargan and then to Les Pavillons-sous-Bois, both in the northeastern suburbs of Paris? Serge remembers them living in a large villa with a garden on rue Sully in Livry-Gargan. He also remembers that when they lived on avenue Jean-Jaurès in Les Pavillons-sous-Bois, the apartment had a bedroom for the housemaid who looked after the three children while their parents went to work in Paris.

The second town, unlike the first, did not have much of a Jewish community. And Samuel, apart from his singing, does not seem to have been very involved in religious activities. Then again, together with his brother-in-law Jacob Bresler, who we mentioned earlier, he founded a Jewish friendly society called “Les originaires de Powonski” (“People from Powonski”) [4]. Samuel and his wife, who were both raised in Paris and spoke fluent French, nevertheless still spoke their parents’ native language, Yiddish. But Serge says that they only used it, as is so often the case, for conversations that they did not want the children to understand.

Was Samuel already working as a sales representative for “Chawtz”, at 26 rue du Château d’Eau in Paris, by then? His post-1945 file states that he was. The company “sold fabrics to women’s clothing manufacturers”. In the 1930s, according to Serge, Fleurette became the first female sales assistant in a womenswear boutique in Passage Brady, near the Grand Boulevards in the 10th district of Paris.

Was it in order to be nearer their work that the family moved back into Paris, to a five-room apartment at 11 rue Martel, also in the 10th district? The Vinograd family is not listed as living in this 5,000-franc-a-year apartment in the 1936 census [5], but Serge remembers going to the local school there for two years, and they were living there at the start of the war.

THE WAR

The anti-Jewish laws

When war broke out on September 3, 1939, Samuel was soon called up. However, he was “discharged on December 28 on account of his family responsibilities” [6].

After France was defeated in June 1940 and Marshal Pétain’s government began collaborating with the Germans, Jews in the occupied zone, along with Communists and Freemasons, were the first people to be targeted. When the decree of September 27, 1940 on “the status of the Jews” required Jews to declare themselves to the French authorities, Samuel went ahead and did just that. He had great faith in the country that had taken him in, besides which, he had become a French citizen: his “optimistic” nature took precedence over reason. Fleurette, however, did not agree. Although she was born in France and also a French citizen, she was firmly opposed to the idea of registering as a Jew at the local police station.

Samuel Vinograd was therefore one of the 149,734 Parisian Jews who registered themselves between October 3 and 20, 1940. He also had his and his wife’s identity cards stamped with the word “Jew,” in red ink. His son Serge and his youngest daughter, Francine, who was born on June 30, 1938, were also declared as “Jews”. His eldest daughter, Balbine, who by that time had married Abraham, known as Albert, Gutmacher when he was called up to join the army, was no longer Samuel’s responsibility. Soon after he enlisted, Albert was taken prisoner [7].

From then on, Jews were not allowed to leave the occupied zone, nor to enter the “prohibited zone”; the German military zone along the French coast. However, the family did not sit back and do nothing. Aware of the danger they were facing, Fleurette wanted to move the children to a safer place. In the meantime, the young Serge spent “many nights staying with non-Jews whenever there was talk of a roundup”. He recalls that at one point, his mother took a bold decision: she “took refuge with a friend in the prohibited zone, in the Manche department on the north coast of France. She worked in a hotel restaurant” and “my father had her address”.

Arrest and deportation

In 1942, while Fleurette was back in Paris for a short visit, the French police turned up at their apartment on rue Martel to arrest Samuel. His wife was quick to react, and the policeman was not overly zealous, most likely because he did not really approve of the orders he had been given. “He was easily persuaded to come back two or three hours later,” says Serge. This gave Samuel time to slip away. “My mother kept in touch with him and saw him again, I think, in 1945, after he himself had been liberated,” Serge says of the policeman, whose name he has since forgotten.

After this wake-up call, it seems that Samuel went into hiding for a while, but it was far from easy. His daughter Balbine and his son-in-law Albert, who had escaped from the prison camp, had false identity papers, supplied by Albert’s father, a communist activist from Livry-Gargan, and were also living in hiding. Samuel however, unlike Fleurette, seems not to have opted for this solution.

He soon went back to their apartment, and it was not long before the police came to arrest him again. This time, there was no nice understanding policeman who looked the other way. Samuel was arrested and taken away to appear in court. Fleurette heard about this and convinced the guards to let her see him. Shortly afterwards, he was released.

After the Vel d’Hiv roundup on July 16 and 17, 1942, when the roundups were increasing, the family decided that it was best to split up. Francine, known as Fanny, was sent to stay with some people in a village about 60 miles from Paris. Serge was sent to a boarding school in Châteaudun, in the Eure-et-Loire department of France. The fees for the year were paid in advance, but as Serge explained in 2024, “Unfortunately, the lycée was commandeered by the Germans to be used as a hospital” and “the school reimbursed the balance”.

Serge never saw his father again, although he did receive a few letters. A resourceful boy, he then “found refuge in a hostel in a village where the local school had a summer camp”. He “managed to find a job as a farm laborer, then worked for a company that threshed wheat, oats, etc., going from farm to farm all year round”.

In July 1944, there was a renewed sense of optimism. The Americans had landed in Normandy on June 6, and although there was heavy fighting, there was little doubt that they would win. As a result, the Germans ramped up their hunt for any remaining Jews. Aloïs Bruner, the Nazi commander in charge of Drancy camp, was obsessed with continuing the convoys to Auschwitz and deporting as many Jews as possible. The number of arrests continued to rise, and roundups were carried out in hospices, nurseries and children’s homes for orphans whose parents had been deported, in search of enough people to fill the cattle cars that made up Convoy 77, the last major convoy from Drancy.

Serge says that in June, although Fleurette was still living out of town, she “came to Paris the day before the arrest”. Wary as ever, “she refused to sleep at home”. “She slept at a friend’s place, but my father wanted to stay home and keep an eye on the apartment”. Not a good idea! “When my mother came back the next day, she found the doors sealed up; she went to the nearest police station pretending to be the cleaning lady and managed to find out where he’d been taken”.

Samuel was arrested on July 3, 1944, and taken to the Police Headquarters at 12:45 on the orders of the assistant director of Jewish Affairs. Fleurette rushed to help. “She then went to the Law Courts and managed to spend an hour with my father and give him a parcel of clothes before he was sent to Drancy. She did all this with false identity papers, but where they came from, I don’t know”, Serge insists.

Shortly afterwards, at 3pm, Samuel was transferred, together with another man, Dr Sigismond Bloch [8], to Drancy camp. When he arrived, he was assigned prisoner number 24699. According to his Drancy search record card, he only had 22 francs on him, which were confiscated by the camp authorities.

Although this was not the first time he had been arrested, according to Serge, he knew that he would not be able to escape this time. His optimism all gone, he penned his final, heart-wrenching letters.

In the early hours of July 31st, buses from Paris arrived at Drancy to take Samuel and 1305 other people – babies, children, teenagers, adults and seniors – to the Bobigny train station. There, in the middle of nowhere, out of sight of the townsfolk, cattle cars were lined up waiting to be loaded with prisoners bound for Auschwitz, under the watchful eyes of angry, ruthless soldiers. A letter from Samuel, which he threw off the train, reached Fleurette a short time later. The grueling journey, in scorching heat and with little or no water, lasted nearly three days.

From that point on, there is no official record of what happened to Samuel. Was he selected to work in the Birkenau camp, and did he perish during the terrible “death marches” in the winter of 1944-45, when the Nazis evacuated almost all the deportees from Auschwitz? This was what one of his fellow prisoners, who survived and returned to France, told Fleurette.

When Fleurette moved back to Paris, their apartment had been looted. She had to “start from scratch”. She never remarried, and raised her two children on her own.

After the war: a family hit hard by deportation

The news from the Auschwitz survivor put an end to Samuel’s family’s hopes of seeing him “come home from the camps”.

Serge, who had been an active member of the Resistance in the Châteaudun area, together with the foreman of the threshing-machine team, moved back to Paris. He resumed his education at the Louis-le-Grand high school and then went on to study at the HEC business school. He later moved to the United States, where he became father and grandfather. Fanny and Balbine stayed on in France.

The Vinograd and Wienerbett families in France lost several close family members, deported from their adopted country.

On Fleurette’s side, her uncle Camille, his wife Berthe and their 18-year-old daughter Claudine were all deported on separate convoys between September and November 1942.

Samuel’s brother Bernard and their sister Esther ( married name Tchertok) were both arrested on rue du Trésor and deported in July 1942, he on convoy 7 and she on convoy 12. Neither of them came home. Bernard [9] who had been invalided out of the army with tuberculosis, was even taken to the Velodrome d’Hiver on a stretcher.

Ruben, known as Robert, Kolnitchanski, a “cousin” who witnessed Samuel’s mother Faiga’s death in 1930, was also deported in 1944, having been arrested in Lyon, in the Rhone department. His son David joined the Resistance, as did Samuel’s brother-in-law Albert Gutmacher, who took part in the liberation of Paris with the FTP. According to Serge, he ran all the way to Drancy to find out who was still there.

Meanwhile, Aloïs Bruner and his Nazi henchmen had left Drancy on August 17. Although the railwaymen resisted by blowing up the tracks, they took with them one last convoy of 51 Jewish “hostages”. The prisoners were then sent to Compiègne, from where they were deported to Buchenwald together with a group of interned Resistance fighters from the nearby Royallieu camp.

When the Nazis abandoned Drancy, the internees were left to fend for themselves. The Resistance then took over the camp.

However, for the prisoners in Auschwitz and the other camps in Poland, Germany and the Alsace region of France, liberation was still a long time coming.

Notes and references

- [1] Record from file 21 P 548 168, dated 10/7/1921, translated from Polish and certified on September 22, 1943 by the Seine District Court and the Police Commissioner (unnamed).

- [2] A record from the Paris Prefecture of Police archives, dated December 10, 1942, mentions 1901 (APP 77 W 1629).

- [3] Rose Vinograd, Samuel’s older sister’s deed of marriage (although it did not take place). She was living with her parents at this address. (Paris city archives, civil status register).

- [4] APP 77W1629-73477. The friendly society was founded on April 30, 1935 and registered with the Seine Prefecture. Its head office was at 10 rue de Lancry. According to the articles of association, the intention was to hold artistic and literary evenings. The members were natives or former residents of Pawonsky (Powonski) and/or their families (Powonski is a suburb of Warsaw). A Police report later stated that the organization had not been very active before the war, but during the war, meetings were held “to collect subscriptions to help prisoners of war”. The society, like most of its sister organizations, made arrangements for its members to be buried in a communal vault in the Jewish section of the Bagneux cemetery. A few people were buried there during the war, but it now serves as a final resting place for people who died in the 1960s and later, even though they do not necessarily have any connection to Powonski.

- [5] APP 77W1629

- [6] APP 77W1629

- [7] Albert joined the Resistance, see below.

- [8] Dr Sigismond Bloch, who was also deported on Convoy 77, survived and returned to France. Might this have been the man who gave the information about Samuel to his widow after the Liberation? There is one record that states that he was one of the Frenchmen still alive in Auschwitz on April 14, 1945. He died in1951.

- [9] Very sick and hospitalized at the end of the war, his wife Fanny, née Fleischman, died in July 1944 and was buried in the Bagneux cemetery.

Français

Français Polski

Polski