Renée LAVAL, née Braschevizky

Introduction to the project

Over the course of the 2023-2024 school year, we focused on the stories of Renée Laval and her brother, Léon Braschevizky, both of whom were deported to Auschwitz but were lucky enough to survive the hell of the camps and return to France after the war.

We were fortunate enough to be able to meet one of their nephews and speak with Renée Laval’s granddaughter, which enabled us to get to know the Braschevizky family a little better.

The aim of the Third Reich was not only to destroy the Jews physically, but also to dehumanize them, to erase their identity and to reduce them to a mere number, without a face, a voice or a past.

We, a group of 12th grade students, are united in our commitment to remembrance, and as such we are determined not to remain silent about the tragic events that took place during the Holocaust. Our aim, through the Convoy 77 project, is to help counter this dehumanization by breathing life into the poignant story of a deported woman, a survivor, a “miracle” woman.

In this in-depth biography of Renée Laval, we delve into the labyrinth of singular human experiences. Each statistic masks a shattered existence, a voice that has fallen silent. Every story represents a candle in the darkness, an act of resistance against oblivion. By recounting Renée Laval’s experience of terror, courage and hope, we are bridging the gap between past and present.

Each and every page of this biography proves that human dignity can prevail, even in the face of dehumanization.

Orianne Multon, 12th grade history-geography, geopolitics and political science student

Note

Before we come to the biography, we need to discuss the spelling of the surname Braschevizky. We noticed that the surnames of Renée Laval and her family were not always spelled the same way, either in the records provided by the Convoy 77 team, or in those we found during our research at the Shoah Memorial. In fact, on the Wall of Names[1] at the Shoah Memorial in Paris, Léon’s surname is spelled Braschevizki. As for Renée Laval, her maiden name is spelled Braschewizky.

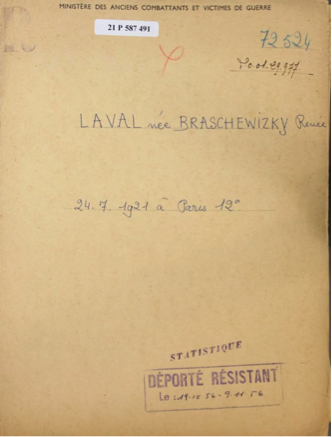

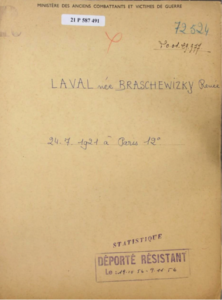

Request for the title of deported resistance fighter.

Source: File on Renée Laval ©Victims of Contemporary Conflicts Archives Division of the Ministry of Defense Historical Service, in Caen, ref. 21 P 587 49132125

Biography

Renée’s parents were Léa Talsky, who was born on October 17, 1897 in Makarov in Russia and Wolf Braschevizky, who was born in 1888 in Jerusalem, now in Israel. The couple lived in Paris and worked in the tailoring trade.

They had four children:

- Marie, who was born in the 12th district of Paris on August 18, 1919,

- Renée, who was born in the 12th district of Paris on July 24, 1921,

- Léon, who was born in the 11th district of Paris on May 16, 1923,

- Jacques, who was born in the 20th district of Paris on April 6, 1926.

The siblings in the 1930s, Jacques, Léon, Renée and Marie

on prizegiving day. Source: private collection

On December 12, 1941, French police arrested Wolf Braschevizky on grounds that he was “Israelite”, meaning Jewish[2], during the “roundup of the notables”[3]. He was interned in the Royallieu camp near Compiègne[4], in the Oise department of France, which was also known by its German name, Frontstalag 122.

He was released on March 13, 1942 because he was thought to be dying. While he was incarcerated, his wife’s hair turned white. She was only 44 years old.

Wolf Braschevizky did not in fact die immediately, but lived until 1953.

In 1938, Marie married Albert Guichard. He was later taken prisoner of war.

Renée got to know Maurice Laval, a Trotskyist resistance fighter[5].

Renée met Maurice Laval at the French Youth Hostels organization[6] in 1940. He was an active member of this group, whose egalitarian ideology reflected that of the French People’s Front.

They were married on May 23, 1942 in the 14th district of Paris.

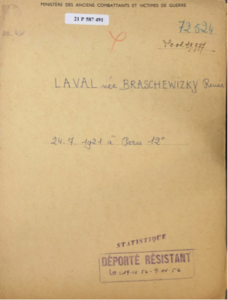

Renée Laval’s marriage certificate.

Source: File on Renée Laval ©Victims of Contemporary Conflicts Archives Division of the Ministry of Defense Historical Service, in Caen, ref. 21 P 587 49132125

Maurice Laval was born on September 8, 1920 in Saint Symphorien, in the Deux-Sèvres department of France. He worked as a draughtsman. As for Renée, she was a secretary.

Photograph of Renée and Maurice in the 1940s. Source: private collection

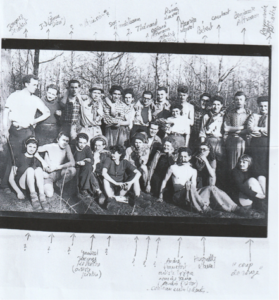

Members of the French Youth Hostels organization. Source: private collection.

During the war, Renée worked as a shorthand typist for a firm called Tréca[7], but was the dismissed because she was Jewish. From 1942 to 1943, Maurice Laval made helicopter rotors at the Ratier factory in Chatillon-sous-Bagneux, in the Hauts-de-Seine department of France, and then became a metalworker for the Gortzé company at 40 rue de Provence in the 9th district of Paris[8].

The couple, who had no children, lived at 103 avenue Verdier in Montrouge, in the Hauts-de-Seine department, and were involved in the Resistance[9]. Renée shared her husband’s political convictions and helped him during Resistance operations.

The arrest

On March 10, 1944, at around 7 p.m., some police officers from the BS2 brigade[10] came to Renée and Maurice Laval’s apartment and took away their typewriter.

Maurice Laval was arrested and interned in the Royallieu transit camp near Compiègne, in the Oise department of France, and was then transferred to the Neuengamme camp in Germany. He was subsequently transferred to the Gross-Rosen, Mauthausen and Sachsenhausen camps, and was then made to take part in a death march between April 21 and May 5, 1945. He survived and came back to France in May 1945.

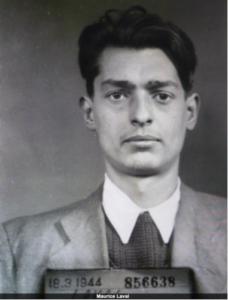

Photo of Maurice Lavaltaken on March 18 ,1944.

Source: Paris prefecture

As for Renée, during her interrogation she admitted to being a member of the Fourth International[11] and admitted that she did some typing for the Resistance. She was thus charged with contravening a French decree passed on June 24, 1939 that “related to the repression of the distribution and circulation of foreign propaganda material”.

She repeated these statements on March 28, 1944, when she was interrogated at the Special Brigade office at the Paris Police Headquarters.

She was imprisoned in the “Depot”[12], a temporary holding center near the Police Headquarters, from March 10 to April 6, 1944.

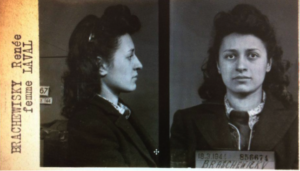

Photo of Renée Laval taken on March 18, 1944. Source: Paris prefecture

She was then transferred to the Petite Roquette prison[13] where she was held from April 6 through May 19, 1944, when was then handed over the to the German authorities, who sent her to Fresnes jail[14] until July 24, 1944. She was then transferred to Drancy camp[15] where she stayed until July 31,1944.

While she was in Drancy, she met up with her brother, Léon[16] who had been arrested on March 11, 1944.

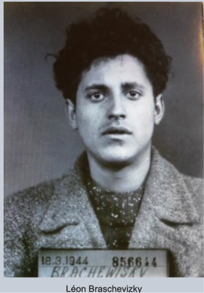

Photo of Léon Braschevizky taken on March 18, 1944

Source: Paris Police Headquarters

The hell of the concentration camp

Both brother and sister were deported to Auschwitz on Convoy 77 on July 31, 44[17].

When she arrived in Auschwitz-Birkenau[18] on August 3, 1944, Renée Laval was selected to go into the concentration camp to work [19]. There she met up with Chaja Broder[20], another deported woman who she had known Paris.

It just so happened that when Léon and their younger brother Jacques were living with their parents at 4 rue Wifried Laurier, in the 14th district of Paris, Chaja Broder was living in the same building.

Chaja was arrested together with her son and some other people on rue Henri Monnier in Paris on July 25, 1944. After a short stay in the Depot, they were transferred to Drancy and then deported on Convoy 77 on July 31, 1944.

When the convoy arrived in Auschwitz-Birkenau, Chaja was separated from her son, René, forever. At the age of 17, he was sent straight to the gas chambers and murdered.

Renée was transferred to the Weisskirchen-Kratzau camp on October, 30, 1944. She remained there from November 4, 1944 to May 10, 1945.

The Weisskirchen-Kratzau camp in Czechoslovakia

Renée was one of a group of women who were selected to work in a weapons factory at Weisskirchen-Kratzau[21].

We found a page on the French website cercleshoah.org that describes a typical day in Weissirchen-Kratzau, as described by two women who escaped from the camp.

The Russian army liberated the camp on May 9, 1945. Renée was repatriated to France on May 20, 1945.

The return to Paris

Renée met up with her brother, Léon, at the reception center at the Lutetia hotel in Paris[22]. Jacques, their younger brother, was waiting for them there. He, Marie and Léa, their mother, went to there every day in the hope of finding Renée and Léon and taking them back home.

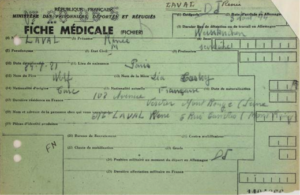

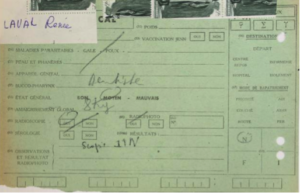

By the time she got back to France, Renée had lost a lot of weight. She lost about 18 pounds during her time in the camps[23] and also had serious dental problems.

Renée Laval’s medical report card. Source: File on Renée Laval

© Victims of Contemporary Conflicts Archives Division of the Ministry of Defense Historical Service, in Caen, ref. 21 P 587 49132125

She was thus reunited with her family, and then also with her husband, Maurice Laval, who also survived his time in the camps.

The couple went back to live in their old apartment at 103 avenue Verdier in Montrouge.

Renée went on to help her friend, Chaja Broder to complete the necessary paperwork to declare the death of her son, René Broder, who had been killed in Auschwitz.

Official recognition of Renée’s status

In December 1953, Renée put together a file to request that she be officially recognized as a Deported Resistance Fighter.

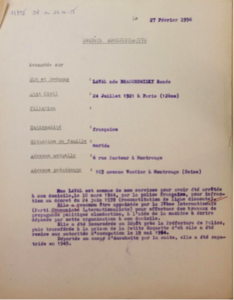

Administrative investigation. Source: File on Renée Laval

© Victims of Contemporary Conflicts Archives Division of the Ministry of Defense Historical Service, in Caen, ref. 21 P 587 49132125

The administrative investigation carried out on February 27, 1956 revealed that the French police had arrested Renée Laval at her home on March 10, 1944, for contravening a French decree passed on June 24, 1939, on the grounds that she was a member of the Fourth International movement and was working on illegal propaganda using a typewriter they had provided.

This was confirmed by Charles Tanguy, who founded the Resistance movement “Travail et Liberté” (Work and Freedom). He stated that Maurice Laval and his wife Renée were active within the movement and in the MLN[24] (Mouvement de Libération nationale, or National Liberation Movement)

Renée Laval was hiding copies of an underground publication “la Sirène et Défense de la France”[25], which she was also responsible for distributing.

Charles Tanguy’s signature was verified by Yvon Morandat, a Companion of the Liberation, of the MLN, ex-MUR.

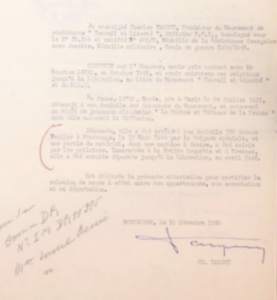

Charles Tanguy’s testimonial. Source: File on Renée Laval

© Victims of Contemporary Conflicts Archives Division of the Ministry of Defense Historical Service, in Caen

In October 1956, Renée was granted the status of deported resistance fighter.

Confirmation of the status of deported resistance fighter.

Source: File on Renée Laval © Victims of Contemporary Conflicts Archives Division of the Ministry of Defense Historical Service, in Caen.

Life after the war

After she came back from the camps, Renée went back to work as a secretary, this time for the USFEN, the French National Education Federation’s Sports Union. Her granddaughter, Sophie, also told us that she liked sport, and although she was less that 5 feet tall, she played basketball!

She no longer supported the Trotskyites, and voted Socialist.

She and Maurice Laval had a son, Jean-François, on May 17, 1946.

Maurice and Renée Laval with their son, Jean-François. Source: private collection

Renée Laval with her son, Jean-François

Source: private collection

In 1968, her son got married.

Renée Laval at her son Jean-François’ wedding

Source: private collection

Jean-François had a daughter, Sophie, on November 4, 1970.

Renée Laval and her granddaughter, Sophie, in the mountains. Source: private collection.

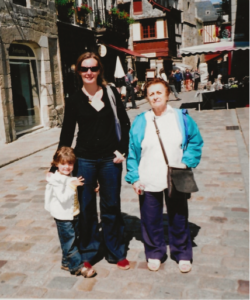

Renée Laval and her granddaughter, Sophie, and her great grandson, Ulysse,

who was born on May 29, 2005, Source: private collection

The four generations of the family: Renée Laval with her son, Jean-François,

her granddaughter, Sophie and her great grandson, Ulysse. Source: private collection

In the 1970s, Renée Laval decided to have her Auschwitz serial number tattoo removed from her arm.

In 2005, Jean Birnbaum, a journalist with the French newspaper Le Monde, wrote a book entitled “Leur jeunesse et la nôtre: L’espérance révolutionnaire au fil des générations” (Their youth and ours: The hope of revolution through the generations). He was interested in finding out how the hope of revolution was passed on from generation to generation within the Trotskyist movement. As part of his research, he interviewed Renée Laval[26].

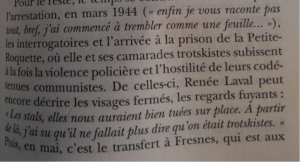

A passage from Jean Birnbaum’s book

This passage (with Renée’s comments in italics) illustrates how afraid she was, as a young woman of 23, when confronted not only with the brutality of the Special Brigade, but also that of the Stalinists[27].

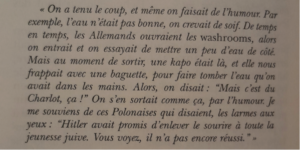

We also very much appreciated the following passage, which describes an incident that took place in Auschwitz-Birkenau. It provides more insight into Renée’s personality.

A passage from Jean Birnbaum’s book.

Renée and her campmates, even in the hell of Auschwitz, kept their sense of humor. Perhaps it helped them to cope with the horror and the dehumanization.

Renée often went to reunions with her fellow deportees, in particular in the town hall of the 20th district of Paris[28], where she met up with Robert Chéramy[29] and Pauline Spulber[30], among others.

Renée Laval and Pauline Kargeman Spulber

Source: private collection

Renée Laval with some of her fellow deportees,

Source: private collection

The Braschevizky siblings in Luxembourg in October 1996

Jacques, Léon, Renée and Marie, Source: private collection

She got divorced from Maurice Laval in January 2002, when she was 81 years old.

Renée Laval died on June 12, 2021 in Châtenay-Malabry, in the Hauts-de-Seine department of France. She was very nearly 100 years old.

Her name is inscribed on the Wall of Names at the Shoah Memorial in Paris[31]

Notes & references

[1] At the Shoah Memorial in Paris there is a Wall of Names that bears the names of all the Jewish people deported from France. It is on the forecourt of the Shoah Memorial in the Marais neighborhood, in the 4th district of Paris.

[2] According to Marie Guichard, Wolf and Léa Braschevizky’s daughter.

[3] The “Round-up of Notables” took place in Paris on December 12, 1941. It was the third major roundup of Jews carried out by the German authorities in France, with the complicity of the Vichy government, since the start of the Occupation during the Second World War. This operation led to the creation of a new sector, the “Jewish camp”, or sector C, within the Royallieu internment camp near Compiègne.

[4] The Royallieu camp in Compiègne, France, was a Nazi transit camp that was in operation from June 1941 to August 1944. It was the second largest internment camp in France during the Occupation, after Drancy.

[5] Trotskyism is a Marxist political philosophy based on the writing, activism and ideology of Leon Trotsky. From 1924 onwards, Trotskyist ideology was primarily characterized by its opposition to the Stalinist vision of communism, challenging the reign of bureaucracy and advocating democracy and freedom of debate within the Communist Party.

[6] On August 28, 1930, Marc Sangnier opened the first youth hostel in France and founded the French League for Youth Hostels (L.F.A.J.). Youth Hostels provide economical accommodation all year round, offer sporting and cultural activities, and bring together young people from different countries in a spirit of respect and tolerance, thus encouraging peace and fellowship between cultures.

[7] The Tréca company made mattresses.

[8] Source: Le Maitron.

[9] Maurice Laval was a deeply dedicated man who made a lasting contribution to history. His biography has been written many times. Born in 1920, he began working in the printing industry and joined the Resistance in the Paris region when he was still quite young. He was arrested and deported. He passed through several concentration camps and survived at 125-mile death march from Berlin to the Baltic Sea. After all that, Maurice Laval went into politices. A committed left-winger, he was one of the founders of the French magazine “L’Observateur”, which later became “Le Nouvel Observateur”. While working for the French newspaper “Combat”, he crossed paths with the famous French writer Albert Camus, and has spoken extensively to high school students about the deportation and the Resistance.

https://clio-cr.clionautes.org/laval-un-resistant-le-siecle-de-maurice-laval-1920-2019.html

https://www.babelio.com/livres/Salaun-Laval-un-resistant/1205659

[10] BS2 stands for Special Brigade No. 2, a police unit that specialized in tracking down domestic enemies during the time of the Vichy regime.

[11] The 4th International emerged from a left-wing oppositionist movement within the Bolshevik Communist Party in 1923, known as Trotskyism. It was founded as a critical response to “Stalinism”, which was accused of destroying the international proletarian revolution for the sake of the unattainable victory for socialism in one country alone.

[12] A small transit prison, a sorting center for suspect individuals, located within the Palais de Justice (law courts) on the Île de la Cité in Paris. Some 110,000 people spent time in it during the Second World War, including around 15,000 Jews. Source: Johanna Lehr, historian.

[13] The Petite Roquette prison, which was located between the Place de la Bastille and Place Voltaire, was for women only.

[14] During the Occupation, Fresnes prison, which was built in 1898, was used by the Germans to imprison and torture resistance fighters and others who opposed them.

[15] Drancy was taken over by the Germans in June 1940. Initially, it was used as an internment camp for prisoners of war and foreign civilians. Then, on August 20, 1941, prompted by the Police Headquarters, it became a camp for Jews.

[16] On March 11, 1944, Léon, having not heard from his sister Renée and brother-in-law Maurice, decided to go to look for them at their home in Montrouge. As soon as he arrived, the French police arrested him. The police, who had arrested Renée and Maurice the day before, had set a trap for him. Léon, who was carrying forged identity papers, was arrested and taken to the depot. He was held at the Conciergerie, then at the Prison de la Santé, and lastly at Fresnes, before being interned at Drancy from July 14 to 31, 1944, where he met up with his sister, Renée.

[17] Convoy 77 was the last large convoy to leave Drancy for Auschwitz, carrying more than 1,300 deportees: 726 were murdered in the gas chambers soon after they arrived, while 291 men and 183 women were selected to go into the camp and work. Only 93 men and 157 women from this convoy survived the hell of the camps.

[18] Auschwitz-Birkenau was a major concentration camp and killing center in Poland. Over 1.1 million Jews were murdered there.

[19] 847 deportees were sent straight to the gas chambers. 183 women selected for forced labor.

[20] See the biographies of Chaja and Léon Broder on the Convoy 77 website.

[21] Kratzau was just outside the town of Chrastava in northern Bohemia, Czechoslovakia. Since 1938, following the Munich Agreement, this town in the Sudetenland region has been annexed to the Third Reich. The women’s concentration camp was built during the Second World War.

[22] From April 26 to September 1, 1945, this hotel on the Left Bank served as a reception and transit center for deportees returning from the hell of the concentration camps.

[23] Her family members say that she lost much more than this. When she came back, she only weighed around 61 pounds.

[24] Le Mouvement de Libération nationale, or National Liberation movement) which was founded on January 5, 1944, brought together the MUR (Mouvements unis de résistance, or United Resistance Movements) and other groups from the northern zone. It thus became the leading Resistance organization, and its aim was to create a unified movement to prepare for the post-Liberation period and, when the time came, to launch a new political organization able to play a key role in French public life.

[25] Défense de la France (Defense of France) was an underground publication with an initial print run of just a few copies, which later grew to 450,000. After the Liberation, it became the newspaper France-Soir.

[26] Information provided by Sophie Laval, Renée’s granddaughter.

[27] Small Trotskyist groups opposed the PCF’s nationalist approach of “To each his own Boche!” and wanted to remain internationalist. They favored brotherhood with “German uniformed workers”.

[28] According to her granddaughter Sophie.

[29] Robert Chéramy was born in Paris on January 31, 1920 and died on August 19, 2002. He was an associate professor of history, a militant Trotskyist and later a French socialist and trade unionist. He was the leader of the SNES Syndicat national des enseignements de second degré, or National Union of Secondary School Teachers and then the FEN Fédération de l’Éducation nationale, or Federation for National Education until. He was then appointed special representative to the French President’s office until 1984, before becoming a member of the French Council of State in extraordinary service until 1988.

[30] Pauline Kargeman Spulber was born in 1925 and died in 2021, two weeks after Renée Laval. She was deported along with Renée Laval on Convoy 77. The two women were close friends.

[31] The Wall of Names at the Shoah Memorial in Paris commemorates all the Jewish people deported from France. It is located on the forecourt of the Shoah Memorial in the Marais neighborhood, in the 4th district of Paris.

Français

Français Polski

Polski